A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of literature by era |

|---|

| Ancient (corpora) |

| Early medieval |

| Medieval by century |

| Early modern by century |

| Modern by century |

| Contemporary by century |

|

|

| Medieval and Renaissance literature |

|---|

| Early medieval |

| Medieval |

|

By century |

| European Renaissance |

|

|

Arabic literature (Arabic: الأدب العربي / ALA-LC: al-Adab al-‘Arabī) is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is Adab, which comes from a meaning of etiquette, and which implies politeness, culture and enrichment.[1]

Arabic literature emerged in the 5th century with only fragments of the written language appearing before then. The Qur'an,[2] would have the greatest lasting effect on Arab culture and its literature. Arabic literature flourished during the Islamic Golden Age, but has remained vibrant to the present day, with poets and prose-writers across the Arab world, as well as in the Arab diaspora, achieving increasing success.[3]

History

Jahili

Jahili literature is the literature of the pre-Islamic period referred to as al-Jahiliyyah, or "the time of ignorance".[4] In pre-Islamic Arabia, markets such as Souq Okaz, in addition to Souq Majanna and Souq Dhi al-Majāz, were destinations for caravans from throughout the peninsula.[4] At these markets poetry was recited, and the dialect of the Quraysh, the tribe in control of Souq Okaz of Mecca, became predominant.[4]

Days of the Arabs, tales in both meter and prose, contains the oldest extant Arabic narratives, focusing on battles and raids.[5]

Poetry

Notable poets of the pre-Islamic period were Abu Layla al-Muhalhel and Al-Shanfara.[4] There were also the poets of the Mu'allaqat, or "the suspended ones", a group of poems said to have been on display in Mecca.[4] These poets are Imru' al-Qais, Tarafah ibn al-‘Abd, Abid Ibn al-Abrass, Harith ibn Hilliza, Amr ibn Kulthum, Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulma, Al-Nabigha al-Dhubiyānī, Antara Ibn Shaddad, al-A'sha al-Akbar, and Labīd ibn Rabī'ah.[4]

Al-Khansa stood out in her poetry of rithā' or elegy.[4] al-Hutay'a was prominent for his madīh, or "panegyric", as well as his hijā' , or "invective".[4]

Prose

As the literature of the Jahili period was transmitted orally and not written, prose represents little of what has been passed down.[4] The main forms were parables (المَثَل al-mathal), speeches (الخطابة al-khitāba), and stories (القِصَص al-qisas).[4]

Quss Bin Sā'ida was a notable Arab ruler, writer, and orator.[4] Aktham Bin Sayfi was also one of the most famous rulers of the Arabs, as well as one of their most renowned speech-givers.[4]

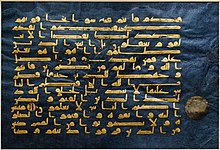

The Qur'an

The Qur'an, the main holy book of Islam, had a significant influence on the Arabic language, and marked the beginning of Islamic literature. Muslims believe it was transcribed in the Arabic dialect of the Quraysh, the tribe of Muhammad.[4][6] As Islam spread, the Quran had the effect of unifying and standardizing Arabic.[4]

Not only is the Qur'an the first work of any significant length written in the language, but it also has a far more complicated structure than the earlier literary works with its 114 surah (chapters) which contain 6,236 ayat (verses). It contains injunctions, narratives, homilies, parables, direct addresses from God, instructions and even comments on how the Qu'ran will be received and understood. It is also admired for its layers of metaphor as well as its clarity, a feature which is mentioned in An-Nahl, the 16th surah.

The 92 Meccan suras, believed to have been revealed to Muhammad in Mecca before the Hijra, deal primarily with 'usul ad-din, or "the principles of religion", whereas the 22 Medinan suras, believed to have been revealed to him after the Hijra, deal primarily with Sharia and prescriptions of Islamic life.[4]

The word qur'an comes from the Arabic root qaraʼa (قرأ), meaning "he read" or "he recited"; in early times the text was transmitted orally. The various tablets and scraps on which its suras were written were compiled under Abu Bakr (573-634), and first transcribed in unified masahif, or copies of the Qur'an, under Uthman (576-656).[4]

Although it contains elements of both prose and poetry, and therefore is closest to Saj or rhymed prose, the Qur'an is regarded as entirely apart from these classifications. The text is believed to be divine revelation and is seen by Muslims as being eternal or 'uncreated'. This leads to the doctrine of i'jaz or inimitability of the Qur'an which implies that nobody can copy the work's style.

Or do they say, “He has fabricated this ˹Quran˺!”? Say, ˹O Prophet,˺ “Produce ten fabricated sûrahs like it and seek help from whoever you can—other than Allah—if what you say is true!”

— 11:13

And if you are in doubt about what We have revealed to Our servant, then produce a sûrah like it and call your helpers other than

Allah, if what you say is true.

But if you do not - and you will never be able to - then fear the Fire, whose fuel is people and stones, prepared for the disbelievers.

— 2:23-24

Say, "If mankind and the jinn gathered in order to produce the like of this Qur’ān, they could not produce the like of it, even if they were to each other assistants."

— 17:88

This doctrine of i'jaz possibly had a slight limiting effect on Arabic literature; proscribing exactly what could be written. Whilst Islam allows Muslims to write, read and recite poetry, the Qur'an states in the 26th sura (Ash-Shu'ara or The Poets) that poetry which is blasphemous, obscene, praiseworthy of sinful acts, or attempts to challenge the Qu'ran's content and form, is forbidden for Muslims.

And as to the poets, those who go astray follow them

Do you not see that they wander about bewildered in every valley? And that they say that which they do not do

Except those who believe and do good works and remember Allah much and defend themselves after they are oppressed; and they who act unjustly shall know to what final place of turning they shall turn back.

— 26:224-227

This may have exerted dominance over the pre-Islamic poets of the 6th century whose popularity may have vied with the Qur'an amongst the people. There was a marked lack of significant poets until the 8th century. One notable exception was Hassan ibn Thabit who wrote poems in praise of Muhammad and was known as the "prophet's poet". Just as the Bible has held an important place in the literature of other languages, The Qur'an is important to Arabic. It is the source of many ideas, allusions and quotes and its moral message informs many works.

Aside from the Qur'an the hadith or tradition of what Muhammed is supposed to have said and done are important literature. The entire body of these acts and words are called sunnah or way and the ones regarded as sahih or genuine of them are collected into hadith. Some of the most significant collections of hadith include those by Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj and Muhammad ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari.

The other important genre of work in Qur'anic study is the tafsir or commentaries Arab writings relating to religion also includes many sermons and devotional pieces as well as the sayings of Ali which were collected in the 10th century as Nahj al-Balaghah or The Peak of Eloquence.

Rashidi

Under the Rashidun, or the "rightly guided caliphs," literary centers developed in the Hijaz, in cities such as Mecca and Medina; in the Levant, in Damascus; and in Iraq, in Kufa and Basra.[4] Literary production—and poetry in particular—in this period served the spread of Islam.[4] There was also poetry to praise brave warriors, to inspire soldiers in jihad, and rithā' to mourn those who fell in battle.[4] Notable poets of this rite include Ka'b ibn Zuhayr, Hasan ibn Thabit, Abu Dhū'īb al-Hudhalī, and Nābigha al-Ja‘dī.[4]

There was also poetry for entertainment often in the form of ghazal.[4] Notables of this movement were Jamil ibn Ma'mar, Layla al-Akhyaliyya, and Umar Ibn Abi Rabi'ah.[4]

Umayyad

The First Fitna, which created the Shia–Sunni split over the rightful caliph, had a great impact on Arabic literature.[4] Whereas Arabic literature—along with Arab society—was greatly centralized in the time of Muhammad and the Rashidun, it became fractured at the beginning of the period of the Umayyad Caliphate, as power struggles led to tribalism.[4] Arabic literature at this time reverted to its state in al-Jahiliyyah, with markets such as Kinasa near Kufa and Mirbad near Basra, where poetry in praise and admonishment of political parties and tribes was recited.[4] Poets and scholars found support and patronage under the Umayyads, but the literature of this period was limited in that it served the interests of parties and individuals, and as such was not a free art form.[4]

Notable writers of this political poetry include Al-Akhtal al-Taghlibi, Jarir ibn Atiyah, Al-Farazdaq, Al-Kumayt ibn Zayd al-Asadi, Tirimmah Bin Hakim, and Ubayd Allah ibn Qays ar-Ruqiyat.[4]

There were also poetic forms of rajaz—mastered by al-'Ajjaj and Ru'uba bin al-Ajjaj—and ar-Rā'uwīyyāt, or "pastoral poetry"—mastered by ar-Rā'ī an-Namīrī and Dhu ar-Rumma.[4]

Abbasid

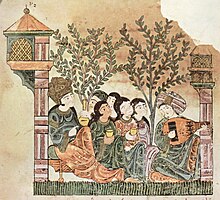

The Abbasid period is generally recognized as the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age, and was a time of significant literary production. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad hosted numerous scholars and writers such as Al-Jahiz and Omar Khayyam.[7][8] A number of stories in the One Thousand and One Nights feature the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid.[9] Al-Hariri of Basra was a notable literary figure of this period.

Some of the important poets in Abbasid literature were: Bashshar ibn Burd, Abu Nuwas, Abu-l-'Atahiya, Muslim ibn al-Walid, Abbas Ibn al-Ahnaf, and Al-Hussein bin ad-Dahhak.[4]

Andalusi

Andalusi literature was produced in Al-Andalus, or Islamic Iberia, from its Muslim conquest in 711 to either the Catholic conquest of Granada in 1492 or the Expulsion of the Moors ending in 1614. Ibn Abd Rabbih's Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd (The Unique Necklace) and Ibn Tufail's Hayy ibn Yaqdhan were influential works of literature from this tradition. Notable literary figures of this period include Ibn Hazm, Ziryab, Ibn Zaydun, Wallada bint al-Mustakfi, Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, Ibn Bajja, Al-Bakri, Ibn Rushd, Hafsa bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya, Ibn Tufail, Ibn Arabi, Ibn Quzman, Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi, and Ibn al-Khatib. The muwashshah and zajal were important literary forms in al-Andalus.

The rise of Arabic literature in al-Andalus occurred in dialogue with the golden age of Jewish culture in Iberia. Most Jewish writers in al-Andalus—while incorporating elements such as rhyme, meter, and themes of classical Arabic poetry—created poetry in Hebrew, but Samuel ibn Naghrillah, Joseph ibn Naghrela, and Ibn Sahl al-Isra'ili wrote poetry in Arabic.[10] Maimonides wrote his landmark Dalãlat al-Hā'irīn (The Guide for the Perplexed) in Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet.[11]

Maghrebi

Fatima al-Fihri founded al-Qarawiyiin University in Fes in 859, recognised as the first university in the world. Particularly from the beginning of the 12th century, with sponsorship from the Almoravid dynasty, the university played an important role in the development of literature in the region, welcoming scholars and writers from throughout the Maghreb, al-Andalus, and the Mediterranean Basin.[12] Among the scholars who studied and taught there were Ibn Khaldoun, al-Bitruji, Ibn Hirzihim (Sidi Harazim), Ibn al-Khatib, and Al-Wazzan (Leo Africanus) as well as the Jewish theologian Maimonides.[12] Sufi literature played an important role in literary and intellectual life in the region from this early period, such as Muhammad al-Jazuli's book of prayers Dala'il al-Khayrat.[13][14]

The Zaydani Library, the library of the Saadi Sultan Zidan Abu Maali, was stolen by Spanish privateers in the 16th century and kept at the El Escorial Monastery.[15]

Mamluk

During the Mamluk Sultanate, Ibn Abd al-Zahir and Ibn Kathir were notable writers of history.[16]

Ottoman

Significant poets of Arabic literature in the time of the Ottoman Empire included ash-Shab adh-Dharif, Al-Busiri author of "Al-Burda", Ibn al-Wardi, Safi al-Din al-Hilli, and Ibn Nubata.[4] Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi wrote on various topics including theology and travel.

Nahda

During the 19th century, a revival took place in Arabic literature, along with much of Arabic culture, and is referred to in Arabic as "al-Nahda", which means "the renaissance".[17] There was a strand of neoclassicism in the Nahda, particularly among writers such as Tahtawi, Shidyaq, Yaziji, and Muwaylihi, who believed in the iḥyāʾ "reanimation" of Arabic literary heritage and tradition.[18][19]

The translation of foreign literature was a major element of the Nahda period. An important translator of the 19th century was Rifa'a al-Tahtawi, who founded the School of Languages (also knowns as School of Translators) in 1835 in Cairo. In the 20th century, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, a Palestinian-Iraqi intellectual living mostly in Bagdad, translated works by William Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett or William Faulkner, among many others.

This resurgence of new writing in Arabic was confined mainly to cities in Syria, Egypt and Lebanon until the 20th century, when it spread to other countries in the region. This cultural renaissance was not only felt within the Arab world, but also beyond, with a growing interest in translating of Arabic works into European languages. Although the use of the Arabic language was revived, particularly in poetry, many of the tropes of the previous literature, which served to make it so ornate and complicated, were dropped.

Just as in the 8th century, when a movement to translate ancient Greek and other literature had helped vitalise Arabic literature, another translation movement during this period would offer new ideas and material for Arabic literature. An early popular success was The Count of Monte Cristo, which spurred a host of historical novels on similar Arabic subjects. Jurji Zaydan and Niqula Haddad were important writers of this genre.[19]

Poetry

During the Nahda, poets like Francis Marrash, Ahmad Shawqi and Hafiz Ibrahim began to explore the possibility of developing the classical poetic forms.[20][21] Some of these neoclassical poets were acquainted with Western literature but mostly continued to write in classical forms, while others, denouncing blind imitation of classical poetry and its recurring themes,[22] sought inspiration from French or English romanticism.

The next generation of poets, the so-called Romantic poets, began to absorb the impact of developments in Western poetry to a far greater extent, and felt constrained by Neoclassical traditions which the previous generation had tried to uphold. The Mahjari poets were emigrants who mostly wrote in the Americas, but were similarly beginning to experiment further with the possibilities of Arabic poetry. This experimentation continued in the Middle East throughout the first half of the 20th century.[23]

Prominent poets of the Nahda, or "Renaissance," were Nasif al-Yaziji;[4] Mahmoud Sami el-Baroudi, Ḥifnī Nāṣif, Ismāʻīl Ṣabrī, and Hafez Ibrahim;[4] Ahmed Shawqi;[4] Jamil Sidqi al-Zahawi, Maruf al Rusafi, Fawzi al-Ma'luf, and Khalil Mutran.[4]

Prose

Rifa'a at-Tahtawi, who lived in Paris from 1826 to 1831, wrote A Paris Profile about his experiences and observations and published it in 1834.[24] Butrus al-Bustani founded the journal Al-Jinan in 1870 and started writing the first encyclopedia in Arabic: Da'irat ul-Ma'arif in 1875.[4] Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq published a number of influential books and was the editor-in-chief of ar-Ra'id at-Tunisi in Tunis and founder of Al-Jawa'ib in Istanbul.[4]

Adib Ishaq spent his career in journalism and theater, working for the expansion of the press and the rights of the people.[4] Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī and Muhammad Abduh founded the revolutionary anti-colonial pan-Islamic journal Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa,[4] Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi, Qasim Amin, and Mustafa Kamil were reformers who influenced public opinion with their writing.[4] Saad Zaghloul was a revolutionary leader and a renowned orator appreciated for his eloquence and reason.[4]

Ibrahim al-Yaziji founded the newspaper an-Najah (النجاح "Achievement") in 1872, the magazine At-Tabib, the magazine Al-Bayan, and the magazine Ad-Diya and translated the Bible into Arabic.[4]Walī ad-Dīn Yakan launched a newspaper called al-Istiqama (الاستقامة, " Righteousness") to challenge Ottoman authorities and push for social reforms, but they shut it down in the same year.[4] Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti, who studied under Muhammad Abduh at Al-Azhar University, was a prolific essayist and published many articles encouraging the people to reawaken and liberate themselves.[4] Suleyman al-Boustani translated the Iliad into Arabic and commented on it.[4] Khalil Gibran and Ameen Rihani were two major figures of the Mahjar movement within the Nahda.[4] Jurji Zaydan founded Al-Hilal magazine in 1892, Yacoub Sarrouf founded Al-Muqtataf in 1876, Louis Cheikho founded the journal Al-Machriq in 1898.[4] Other notable figures of the Nahda were Mostafa Saadeq Al-Rafe'ie and May Ziadeh.[4]

Muhammad al-Kattani, founder of one of the first arabophone newspapers in Morocco, called At-Tā'ūn, and author of several poetry collections, was a leader of the Nahda in the Maghreb.[25][26]

Modern literature

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Arabic novel became one of the most important forms of expression in Arabic literature.[27] The rise of an efendiyya, an elite, secularist urban class with a Western education, gave way to new forms of literary expression: modern Arabic fiction.[19] This new bourgeois class of literati used theater from the 1850s, starting in Lebanon, and the private press from the 1860s and 1870s to spread its ideas, challenge traditionalists, and establish its position in a rapidly transforming society.[19]

The modern Arabic novel, particularly as a means of social critique and reform, has its roots in a deliberate departure from the traditionalist language and aesthetics of classical adab for "less embellished but more entertaining narratives."[19] This direction began with translations from French and English, followed by social romances by Salīm al-Bustānī and other writers—particularly Christians.[19] Khalil al-Khuri's narrative Way, Idhan Lastu bi-Ifranjī! (1859-1860) was an early example.[19]

The emotionalism of early 20th century writers such as Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti and Kahlil Gibran, who wrote with heavy moralism and sentimentality, equated the novel as a literary form with imported Western ideas and "shallow sentimentalism."[19] Writers such as Muhammad Taimur of Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha "the Modern School," calling for an adab qawmī "national literature," largely avoided the novel and experimented with short stories instead.[19][28] Mohammed Hussein Heikal's 1913 novel Zaynab was a compromise, as it included heavy sentimentality but portrayed local personality and characters.[19]

Throughout the 20th century, Arabic writers in poetry, prose and theatre plays have reflected the changing political and social climate of the Arab world. Anti-colonial themes were prominent early in the 20th century, with writers continuing to explore the region's relationship with the West. Internal political upheaval has also been a challenge, with writers suffering censorship or persecution.

The interwar period featured writers such as Taha Hussein, author of Al-Ayyām, Ibrahim al-Mazini, Abbas Mahmoud al-Aqqad, and Tawfiq al-Hakim.[19] The acceptance of suffering in al-Hakim's 1934 Awdat ar-rūḥ , is exemplary of the disappointment that prevailed over the idealism of the new middle class.[19] As a result of increasing industrialization and urbanization, binary struggles such as the "materialism of the West" against the "spiritualism of the East," "progressive individuals and a backward, ignorant society," and "a city-versus-countryside divide" were common themes in the literature of this period and since.[19]

There are many contemporary Arabic writers, such as Mahmoud Saeed (Iraq) who wrote Bin Barka Ally, and I Am The One Who Saw (Saddam City). Other contemporary writers include Sonallah Ibrahim and Abdul Rahman Munif, who were imprisoned by the government for their critical opinions. At the same time, others who had written works supporting or praising governments, were promoted to positions of authority within cultural bodies. Nonfiction writers and academics have also produced political polemics and criticisms aiming to re-shape Arabic politics. Some of the best known are Taha Hussein's The Future of Culture in Egypt, which was an important work of Egyptian nationalism, and the works of Nawal el-Saadawi, who campaigned for women's rights. Tayeb Salih from Sudan and Ghassan Kanafani from Palestine are two other writers who explored identity in relationship to foreign and domestic powers, the former writing about colonial/post-colonial relationships, and the latter on the repercussions of the Palestinian struggle.

Poetry

Mention no longer the driver on his night journey and the wide striding camels, and give up talk of morning dew and ruins.

I no longer have any taste for love songs on dwellings which already went down in seas of odes.

So, too, the ghada, whose fire, fanned by the sighs of those enamored of it, cries out to the poets: "Alas for my burning!"

If a steamer leaves with my friends on sea or land, why should I direct my complaints to the camels?

—Excerpt from Francis Marrash's Mashhad al-ahwal (1870), translated by Shmuel Moreh.[22]

After World War II, there was a largely unsuccessful movement by several poets to write poems in free verse (shi'r hurr). Iraqi poets Badr Shakir al-Sayyab and Nazik Al-Malaika (1923-2007) are considered to be the originators of free verse in Arabic poetry. Most of these experiments were abandoned in favour of prose poetry, of which the first examples in modern Arabic literature are to be found in the writings of Francis Marrash,[29] and of which two of the most influential proponents were Nazik al-Malaika and Iman Mersal. The development of modernist poetry also influenced poetry in Arabic. More recently, poets such as Adunis have pushed the boundaries of stylistic experimentation even further.

An example of modern poetry in classical Arabic style with themes of Pan-Arabism is the work of Aziz Pasha Abaza. He came from Abaza family which produced notable Arabic literary figures including Ismail Pasha Abaza, Fekry Pasha Abaza, novelist Tharwat Abaza, and Desouky Bek Abaza, among others.[30][31]

Poetry retains a very important status in the Arab world. Mahmoud Darwish was regarded as the Palestinian national poet, and his funeral was attended by thousands of mourners. Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani addressed less political themes, but was regarded as a cultural icon, and his poems provide the lyrics for many popular songs.

Novels

Two distinct trends can be found in the nahda period of revival. The first was a neo-classical movement which sought to rediscover the literary traditions of the past, and was influenced by traditional literary genres—such as the maqama—and works like One Thousand and One Nights. In contrast, a modernist movement began by translating Western modernist works—primarily novels—into Arabic.

In the 19th century, individual authors in Syria, Lebanon and Egypt created original works by imitating classical narrative genres: Ahmad Faris Shidyaq with Leg upon Leg (1855), Khalil Khoury with Yes... so I am not a Frank (1859), Francis Marrash with The Forest of Truth (1865), Salim al-Bustani with At a Loss in the Levantine Gardens (1870), and Muhammad al-Muwaylihi with Isa ibn Hisham's Tale (1907).[32] This trend was furthered by Jurji Zaydan (author of many historical novels), Khalil Gibran, Mikha'il Na'ima and Muhammad Husayn Haykal (author of Zaynab). Meanwhile, female writer Zaynab Fawwaz's first novel Ḥusn al-'Awāqib aw Ghādah al-Zāhirah (The Happy Ending, 1899) was also influential.[33] According to the authors of the Encyclopedia of the Novel:

Almost each of the above have been claimed as the first Arabic novel, which goes to suggest that the Arabic novel emerged from several rehearsals and multiple beginnings rather than from one single origin. Given that the very Arabic word "riwaya", which is now used exclusively in reference to the "novel", has traditionally conjured up a tangle of narrative genres , it might not be unfair to contend that the Arabic novel owes its early formation not only to the appropriation of the novel genre from Europe but also, and more importantly, to the revival and transformation of traditional narrative genres in the wake of Napoleon's 1798 expedition into Egypt and the Arab world's firsthand encounter with industrialized imperial Europe.[32]

A common theme in the modern Arabic novel is the study of family life with obvious resonances of the wider family of the Arabic world.[according to whom?] Many of the novels have been unable to avoid the politics and conflicts of the region with war often acting as background to intimate family dramas. The works of Naguib Mahfuz depict life in Cairo, and his Cairo Trilogy, describing the struggles of a modern Cairene family across three generations, won him a Nobel prize for literature in 1988. He was the first Arabic writer to win the prize.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Arabic_LiteratureText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk