A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Brahmi Brāhmī | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | At least by the 3rd century BCE[1] to 5th century CE |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, Tamil, Saka, Tocharian, Telugu, Elu |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Numerous descendant writing systems including:

Devanagari, Kaithi, Sylheti Nagri, Gujarati, Modi, Bengali, Assamese, Sharada, Tirhuta, Odia, Kalinga, Nepalese, Gurmukhi, Khudabadi, Multani, Dogri, Tocharian, Meitei, Lepcha, Tibetan, Bhaiksuki, Siddhaṃ, Takri, ʼPhags-pa

|

Sister systems | Kharosthi |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Brah (300), Brahmi |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Brahmi |

| U+11000–U+1107F | |

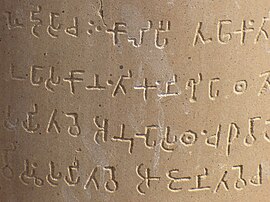

Brahmi (/ˈbrɑːmi/ BRAH-mee; 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻; ISO: Brāhmī) is a writing system of ancient India[2] that appeared as a fully developed script in the 3rd century BCE.[3] Its descendants, the Brahmic scripts, continue to be used today across Southern and Southeastern Asia.[4][5][6]

Brahmi is an abugida which uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. The writing system only went through relatively minor evolutionary changes from the Mauryan period (3rd century BCE) down to the early Gupta period (4th century CE), and it is thought that as late as the 4th century CE, a literate person could still read and understand Mauryan inscriptions.[7] Sometime thereafter, the ability to read the original Brahmi script was lost. The earliest (indisputably dated) and best-known Brahmi inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, dating to 250–232 BCE.

The decipherment of Brahmi became the focus of European scholarly attention in the early 19th-century during East India Company rule in India, in particular in the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta.[8][9][10][11] Brahmi was deciphered by James Prinsep, the secretary of the Society, in a series of scholarly articles in the Society's journal in the 1830s.[12][13][14][15] His breakthroughs built on the epigraphic work of Christian Lassen, Edwin Norris, H. H. Wilson and Alexander Cunningham, among others.[16][17][18]

The origin of the script is still much debated, with most scholars stating that Brahmi was derived from or at least influenced by one or more contemporary Semitic scripts. Some non-specialists favour the idea of an indigenous origin or connection to the much older and as yet undeciphered Indus script,[19][20] although this is not generally accepted by epigraphists.[21]

Brahmi was at one time referred to in English as the "pin-man" script,[22] likening the characters to stick figures. It was known by a variety of other names, including "lath", "Laṭ", "Southern Aśokan", "Indian Pali" or "Mauryan" (Salomon 1998, p. 17), until the 1880s when Albert Étienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie, based on an observation by Gabriel Devéria, associated it with the Brahmi script, the first in a list of scripts mentioned in the Lalitavistara Sūtra. Thence the name was adopted in the influential work of Georg Bühler, albeit in the variant form "Brahma".[23]

The Gupta script of the 5th century is sometimes called "Late Brahmi". From the 6th century onward, the Brahmi script diversified into numerous local variants, grouped as the Brahmic family of scripts. Dozens of modern scripts used across South and South East Asia have descended from Brahmi, making it one of the world's most influential writing traditions.[24] One survey found 198 scripts that ultimately derive from it.[25]

Among the inscriptions of Ashoka (c. 3rd century BCE) written in the Brahmi script a few numerals were found, which have come to be called the Brahmi numerals.[26] The numerals are additive and multiplicative and, therefore, not place value;[26] it is not known if their underlying system of numeration has a connection to the Brahmi script.[26] But in the second half of the 1st millennium CE, some inscriptions in India and Southeast Asia written in scripts derived from the Brahmi did include numerals that are decimal place value, and constitute the earliest existing material examples of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, now in use throughout the world.[27] The underlying system of numeration, however, was older, as the earliest attested orally transmitted example dates to the middle of the 3rd century CE in a Sanskrit prose adaptation of a lost Greek work on astrology.[28][29][30]

Texts

The Brahmi script is mentioned in the ancient Indian texts of the three major Dharmic religions: Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, as well as their Chinese translations.[32][33] For example, the 10th chapter of the Lalitavistara Sūtra (c. 200–300 CE),[34] titled the Lipisala samdarshana parivarta, lists 64 lipi (scripts), with the Brahmi script starting the list. The Lalitavistara Sūtra states that young Siddhartha, the future Gautama Buddha (~500 BCE), mastered philology, Brahmi and other scripts from the Brahmin Lipikāra and Deva Vidyāsiṃha at a school.[32][35]

A list of eighteen ancient scripts is found in the early Jaina texts, such as the Paṇṇavaṇā Sūtra (2nd century BCE) and the Samavāyāṅga Sūtra (3rd century BCE).[36][37] These Jain script lists include Brahmi at number 1 and Kharoṣṭhi at number 4, but also Javanaliya (probably Greek) and others not found in the Buddhist lists.[37]

Origins

While the contemporary Kharoṣṭhī script is widely accepted to be a derivation of the Aramaic alphabet, the genesis of the Brahmi script is less straightforward. Salomon reviewed existing theories in 1998,[4] while Falk provided an overview in 1993.[38]

Early theories proposed a pictographic-acrophonic origin for the Brahmi script, on the model of the Egyptian hieroglyphic script. These ideas however have lost credence, as they are "purely imaginative and speculative".[39] Similar ideas have tried to connect the Brahmi script with the Indus script, but they remain unproven, and particularly suffer from the fact that the Indus script is as yet undeciphered.[39]

The mainstream view is that Brahmi has an origin in Semitic scripts (usually Aramaic). This is accepted by the vast majority of script scholars since the publications by Albrecht Weber (1856) and Georg Bühler's On the origin of the Indian Brahma alphabet (1895).[40][5] Bühler's ideas have been particularly influential, though even by the 1895 date of his opus on the subject, he could identify no fewer than five competing theories of the origin, one positing an indigenous origin and the others deriving it from various Semitic models.[41]

The most disputed point about the origin of the Brahmi script has long been whether it was a purely indigenous development or was borrowed or derived from scripts that originated outside India. Goyal (1979)[42] noted that most proponents of the indigenous view are fringe Indian scholars, whereas the theory of Semitic origin is held by "nearly all" Western scholars, and Salomon agrees with Goyal that there has been "nationalist bias" and "imperialist bias" on the two respective sides of the debate.[43] In spite of this, the view of indigenous development had been prevalent among British scholars writing prior to Bühler: a passage by Alexander Cunningham, one of the earliest indigenous origin proponents, suggests that, in his time, the indigenous origin was a preference of British scholars in opposition to the "unknown Western" origin preferred by continental scholars.[41] Cunningham in the seminal Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum of 1877 speculated that Brahmi characters were derived from, among other things, a pictographic principle based on the human body,[44] but Bühler noted that, by 1891, Cunningham considered the origins of the script uncertain.

Most scholars believe that Brahmi was likely derived from or influenced by a Semitic script model, with Aramaic being a leading candidate.[47] However, the issue is not settled due to the lack of direct evidence and unexplained differences between Aramaic, Kharoṣṭhī, and Brahmi.[48] Though Brahmi and the Kharoṣṭhī script share some general features, the differences between the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts are "much greater than their similarities", and "the overall differences between the two render a direct linear development connection unlikely", states Richard Salomon.[49]

Virtually all authors accept that regardless of the origins, the differences between the Indian script and those proposed to have influenced it are significant. The degree of Indian development of the Brahmi script in both the graphic form and the structure has been extensive. It is also widely accepted that theories about the grammar of the Vedic language probably had a strong influence on this development. Some authors – both Western and Indian – suggest that Brahmi was borrowed or inspired by a Semitic script, invented in a short few years during the reign of Ashoka, and then used widely for Ashokan inscriptions.[48] In contrast, some authors reject the idea of foreign influence.[50][51]

Bruce Trigger states that Brahmi likely emerged from the Aramaic script (with extensive local development), but there is no evidence of a direct common source.[52] According to Trigger, Brahmi was in use before the Ashoka pillars, at least by the 4th or 5th century BCE in Sri Lanka and India, while Kharoṣṭhī was used only in northwest South Asia (eastern parts of modern Afghanistan and neighboring regions of Pakistan) for a while before it died out in the third century.[52] According to Salomon, evidence of the use of Kharoṣṭhī is found primarily in Buddhist records and those of Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, Indo-Parthian, and Kushana dynasty era.[49]

Justeson and Stephens proposed that this inherent vowel system in Brahmi and Kharoṣṭhī developed by transmission of a Semitic abjad through the recitation of its letter values. The idea is that learners of the source alphabet recite the sounds by combining the consonant with an unmarked vowel, e.g. /kə/, /kʰə/, /gə/, and in the process of borrowing into another language, these syllables are taken to be the sound values of the symbols. They also accepted the idea that Brahmi was based on a North Semitic model.[53]

Semitic hypothesis

Many scholars link the origin of Brahmi to Semitic script models, particularly Aramaic.[40] The explanation of how this might have happened, the particular Semitic script, and the chronology of the derivation have been the subject of much debate. Bühler followed Max Weber in connecting it particularly to Phoenician, and proposed an early 8th century BCE date[54] for the borrowing. A link to the South Semitic scripts, a less prominent branch of the Semitic script family, has occasionally been proposed, but has not gained much acceptance.[55] Finally, the Aramaic script being the prototype for Brahmi has been the more preferred hypothesis because of its geographic proximity to the Indian subcontinent, and its influence likely arising because Aramaic was the bureaucratic language of the Achaemenid empire. However, this hypothesis does not explain the mystery of why two very different scripts, Kharoṣṭhī and Brahmi, developed from the same Aramaic. A possible explanation might be that Ashoka created an imperial script for his edicts, but there is no evidence to support this conjecture.[56]

The chart below shows the close resemblance that Brahmi has with the first four letters of Semitic script, the first column representing the Phoenician alphabet.

| Letter | Name[57] | Phoneme | Origin | Corresponding letter in | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Hieroglyphs | Proto-Sinaitic | Aramaic | Hebrew | Syriac | Greek | Brahmi | |||||||||

| 𐤀 | ʾālep | ʾ [ʔ] | 𓃾 | 𐡀 | א | ܐ | Αα | 𑀅 | |||||||||

| 𐤁 | bēt | b [b] | 𓉐 | 𐡁 | ב | ܒ | Ββ | 𑀩 | |||||||||

| 𐤂 | gīml | g [ɡ] | 𓌙 | 𐡂 | ג | ܓ | Γγ | 𑀕 | |||||||||

| 𐤃 | dālet | d [d] | 𓇯 | 𐡃 | ד | ܕ | Δδ | 𑀥 | |||||||||

Bühler's hypothesis

According to the Semitic hypothesis as laid out by Bühler in 1898, the oldest Brahmi inscriptions were derived from a Phoenician prototype.[58][note 1] Salomon states Bühler's arguments are "weak historical, geographical, and chronological justifications for a Phoenician prototype". Discoveries made since Bühler's proposal, such as of six Mauryan inscriptions in Aramaic, suggest Bühler's proposal about Phoenician as weak. It is more likely that Aramaic, which was virtually certainly the prototype for Kharoṣṭhī, also may have been the basis for Brahmi. However, it is unclear why the ancient Indians would have developed two very different scripts.[56]