A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Parts of this article (those related to images of new issuance of coins and banknotes (see zh:第五套人民币#第三版)) need to be updated. (September 2021) |

| 人民币 (Chinese) RMB | |

|---|---|

Renminbi banknotes | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | CNY (numeric: 156) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Unit | yuán (元 / 圆) |

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency do(es) not have a morphological plural distinction. |

| Symbol | ¥ |

| Nickname | kuài (块) |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄10 | jiǎo (角) |

| 1⁄100 | fēn (分) |

| Nickname | |

| jiǎo (角) | máo (毛) |

| Banknotes | |

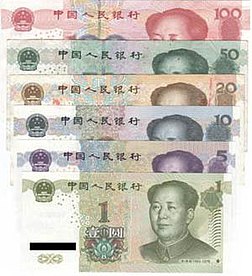

| Freq. used | ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, ¥100 |

| Rarely used | ¥0.1, ¥0.5 |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | ¥0.1, ¥0.5, ¥1 |

| Rarely used | ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05 |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 1948 |

| Replaced | Nationalist-issued yuan |

| User(s) | China (Mainland China) Wa State |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | People's Bank of China |

| Website | www |

| Printer | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation |

| Website | www |

| Mint | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation |

| Website | www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 2.5% (2017) |

| Source | [1] [2] |

| Method | CPI |

| Pegged with | Partially, to a basket of trade-weighted international currencies |

| Renminbi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Renminbi" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 人民币 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 人民幣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "People's Currency" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 圆 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圓 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "circle" (ie. a coin) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The renminbi (Chinese: 人民币; pinyin: Rénmínbì; lit. 'People's Currency'; symbol: ¥; ISO code: CNY; abbreviation: RMB) is the official currency of the People's Republic of China.[a] It is the world's fifth most traded currency as of April 2022.[3]

The yuan (Chinese: 元 or simplified Chinese: 圆; traditional Chinese: 圓; pinyin: yuán) is the basic unit of the renminbi. One yuan is divided into 10 jiao (Chinese: 角; pinyin: jiǎo), and the jiao is further subdivided into 10 fen (Chinese: 分; pinyin: fēn). The renminbi is issued by the People's Bank of China, the monetary authority of China.[4]

The word yuan is widely used to refer to the Chinese currency generally, especially in international contexts.[b]

Valuation

Until 2005, the value of the renminbi was pegged to the US dollar. As China pursued its transition from central planning to a market economy and increased its participation in foreign trade, the renminbi was devalued to increase the competitiveness of Chinese industry. It has previously been claimed that the renminbi's official exchange rate was undervalued by as much as 37.5% against its purchasing power parity.[5] However, more recently, appreciation actions by the Chinese government, as well as quantitative easing measures taken by the American Federal Reserve and other major central banks, have caused the renminbi to be within as little as 8% of its equilibrium value by the second half of 2012.[6] Since 2006, the renminbi exchange rate has been allowed to float in a narrow margin around a fixed base rate determined with reference to a basket of world currencies. The Chinese government has announced that it will gradually increase the flexibility of the exchange rate. As a result of the rapid internationalization of the renminbi, it became the world's 8th most traded currency in 2013,[7] 5th by 2015,[8] but 6th in 2019.[9]

On 1 October 2016, the renminbi became the first emerging market currency to be included in the IMF's special drawing rights basket, the basket of currencies used by the IMF as a reserve currency.[10] Its initial weighting in the basket was 10.9%.[11]: 259

| Current CNY exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

Terminology

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

| Chinese | pinyin | English | Literal translation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal currency name | 人民币 | rénmínbì | renminbi | "people's currency" |

| Formal name for 1 unit | 元 or 圆 | yuán | yuan | "unit", "circle" |

| Formal name for 1⁄10 unit | 角 | jiǎo | jiao | "corner" |

| Formal name for 1⁄100 unit | 分 | fēn | fen | "fraction", "cent" |

| Colloquial name for 1 unit | 块 | kuài | kuai or quay[12] | "piece" |

| Colloquial name for 1⁄10 unit | 毛 | máo | mao | "feather" |

The ISO code for the renminbi is CNY, the PRC's country code (CN) plus "Y" from "yuan".[13] Hong Kong markets that trade renminbi at free-floating rates use the unofficial code CNH. This is to distinguish the rates from those fixed by Chinese central banks on the mainland.[14] The abbreviation RMB is not an ISO code but is sometimes used like one by banks and financial institutions.

The currency symbol for the yuan unit is ¥, but when distinction from the Japanese yen is required RMB (e.g. RMB 10,000) or ¥ RMB (e.g. ¥10,000 RMB) is used. However, in written Chinese contexts, the Chinese character for yuan (Chinese: 元; lit. 'constituent', 'part') or, in formal contexts Chinese: 圆; lit. 'round', usually follows the number in lieu of a currency symbol.

Renminbi is the name of the currency while yuan is the name of the primary unit of the renminbi. This is analogous to the distinction between "sterling" and "pound" when discussing the official currency of the United Kingdom.[13] Jiao and fen are also units of renminbi.

In everyday Mandarin, kuai (Chinese: 块; pinyin: kuài; lit. 'piece') is usually used when discussing money and "renminbi" or "yuan" are rarely heard.[13] Similarly, Mandarin speakers typically use mao (Chinese: 毛; pinyin: máo) instead of jiao.[13] For example, ¥8.74 might be read as 八块七毛四 (pinyin: bā kuài qī máo sì) in everyday conversation, but read 八元七角四分 (pinyin: bā yuán qī jiǎo sì fēn) formally.

Renminbi is sometimes referred to as the "redback", a play on "greenback", a slang term for the US dollar.[15]

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

The various currencies called yuan or dollar issued in mainland China as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and Singapore were all derived from the Spanish American silver dollar, which China imported in large quantities from Spanish America from the 16th to 20th centuries. The first locally minted silver dollar or yuan accepted all over Qing dynasty China (1644–1912) was the silver dragon dollar introduced in 1889. Various banknotes denominated in dollars or yuan were also introduced, which were convertible to silver dollars until 1935 when the silver standard was discontinued and the Chinese yuan was made fabi (法币; legal tender fiat currency).

The renminbi was introduced by the People's Bank of China in December 1948, about a year before the establishment of the People's Republic of China. It was issued only in paper form at first, and replaced the various currencies circulating in the areas controlled by the Communists. One of the first tasks of the new government was to end the hyperinflation that had plagued China in the final years of the Kuomintang (KMT) era. That achieved, a revaluation occurred in 1955 at the rate of 1 new yuan = 10,000 old yuan.

As the Chinese Communist Party took control of ever larger territories in the latter part of the Chinese Civil War, its People's Bank of China began to issue a unified currency in 1948 for use in Communist-controlled territories. Also denominated in yuan, this currency was identified by different names, including "People's Bank of China banknotes" (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行钞票; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行鈔票; from November 1948), "New Currency" (simplified Chinese: 新币; traditional Chinese: 新幣; from December 1948), "People's Bank of China notes" (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行券; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行券; from January 1949), "People's Notes" (人民券, as an abbreviation of the last name), and finally "People's Currency", or "renminbi", from June 1949.[16]

Era of the command economy

From 1949 until the late 1970s, the state fixed China's exchange rate at a highly overvalued level as part of the country's import-substitution strategy. During this time frame, the focus of the state's central planning was to accelerate industrial development and reduce China's dependence on imported manufactured goods. The overvaluation allowed the government to provide imported machinery and equipment to priority industries at a relatively lower domestic currency cost than otherwise would have been possible.

Transition to an equilibrium exchange rate

China's transition by the mid-1990s to a system in which the value of its currency was determined by supply and demand in a foreign exchange market was a gradual process spanning 15 years that involved changes in the official exchange rate, the use of a dual exchange rate system, and the introduction and gradual expansion of markets for foreign exchange.

The most important move to a market-oriented exchange rate was an easing of controls on trade and other current account transactions, as occurred in several very early steps. In 1979, the State Council approved a system allowing exporters and their provincial and local government owners to retain a share of their foreign exchange earnings, referred to as foreign exchange quotas. At the same time, the government introduced measures to allow retention of part of the foreign exchange earnings from non-trade sources, such as overseas remittances, port fees paid by foreign vessels, and tourism.

As early as October 1980, exporting firms that retained foreign exchange above their own import needs were allowed to sell the excess through the state agency responsible for the management of China's exchange controls and its foreign exchange reserves, the State Administration of Exchange Control. Beginning in the mid-1980s, the government sanctioned foreign exchange markets, known as swap centres, eventually in most large cities.

The government also gradually allowed market forces to take the dominant role by introducing an "internal settlement rate" of ¥2.8 to 1 US dollar which was a devaluation of almost 100%.

Foreign exchange certificates, 1980–1994

In the process of opening up China to external trade and tourism, transactions with foreign visitors between 1980 and 1994 were done primarily using Foreign exchange certificates (外汇券, waihuiquan) issued by the Bank of China.[17][18][19] Foreign currencies were exchangeable for FECs and vice versa at the renminbi's prevailing official rate which ranged from US$1 = ¥2.8 FEC to ¥5.5 FEC. The FEC was issued as banknotes from ¥0.1 to ¥100, and was officially at par with the renminbi. Tourists used FECs to pay for accommodation as well as tourist and luxury goods sold in Friendship Stores. However, given the non-availability of foreign exchange and Friendship Store goods to the general public, as well as the inability of tourists to use FECs at local businesses, an illegal black market developed for FECs where touts approached tourists outside hotels and offered over ¥1.50 RMB in exchange for ¥1 FEC. In 1994, as a result of foreign exchange management reforms approved by the 14th CPC Central Committee, the renminbi was officially devalued from US$1 = ¥5.5 to over ¥8, and the FEC was retired at ¥1 FEC = ¥1 RMB in favour of tourists directly using the renminbi.

Evolution of exchange policy since 1994

In November 1993, the Third Plenum of the Fourteenth CPC Central Committee approved a comprehensive reform strategy in which foreign exchange management reforms were highlighted as a key element for a market-oriented economy. A floating exchange rate regime and convertibility for renminbi were seen as the ultimate goal of the reform. Conditional convertibility under current account was achieved by allowing firms to surrender their foreign exchange earning from current account transactions and purchase foreign exchange as needed. Restrictions on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was also loosened and capital inflows to China surged.

Convertibility

During the era of the command economy, the value of the renminbi was set to unrealistic values in exchange with Western currency and severe currency exchange rules were put in place, hence the dual-track currency system from 1980 to 1994 with the renminbi usable only domestically, and with Foreign Exchange Certificates (FECs) used by foreign visitors.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, China worked to make the renminbi more convertible. Through the use of swap centres, the exchange rate was eventually brought to more realistic levels of above ¥8/US$1 in 1994 and the FEC was discontinued. It stayed above ¥8/$1 until 2005 when the renminbi's peg to the dollar was loosened and it was allowed to appreciate.

As of 2013, the renminbi is convertible on current accounts but not capital accounts. The ultimate goal has been to make the renminbi fully convertible. However, partly in response to the Asian financial crisis in 1998, China has been concerned that the Chinese financial system would not be able to handle the potential rapid cross-border movements of hot money, and as a result, as of 2012, the currency trades within a narrow band specified by the Chinese central government.

Following the internationalization of the renminbi, on 30 November 2015, the IMF voted to designate the renminbi as one of several main world currencies, thus including it in the basket of special drawing rights. The renminbi became the first emerging market currency to be included in the IMF's SDR basket on 1 October 2016.[10] The other main world currencies are the dollar, the euro, sterling, and the yen.[20]

Digital renminbi

In October 2019, China's central bank, PBOC, announced that a digital reminbi is going to be released after years of preparation.[21] This version of the currency, also called DCEP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment),[22] can be “decoupled” from the banking system to give visiting tourists a taste of the nation's burgeoning cashless society.[23] The announcement received a variety of responses: some believe it is more about domestic control and surveillance.[24] Some argue that the real barriers to internationalisation of the renminbi are China's capital controls, which it has no plans to remove. Maximilian Kärnfelt, an expert at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, said that a digital renminbi "would not banish many of the problems holding the renminbi back from more use globally". He went on to say, "Much of China's financial market is still not open to foreigners and property rights remain fragile."[25]

The PBOC has filed more than 80 patents surrounding the integration of a digital currency system, choosing to embrace the blockchain technology. The patents reveal the extent of China's digital currency plans. The patents, seen and verified by the Financial Times, include proposals related to the issuance and supply of a central bank digital currency, a system for interbank settlements that uses the currency, and the integration of digital currency wallets into existing retail bank accounts. Several of the 84 patents reviewed by the Financial Times indicate that China may plan to algorithmically adjust the supply of a central bank digital currency based on certain triggers, such as loan interest rates. Other patents are focused on building digital currency chip cards or digital currency wallets that banking consumers could potentially use, which would be linked directly to their bank accounts. The patent filings also point to the proposed ‘tokenomics’ being considered by the DCEP working group. Some patents show plans towards programmed inflation control mechanisms. While the majority of the patents are attributed to the PBOC's Digital Currency Research Institute, some are attributed to state-owned corporations or subsidiaries of the Chinese central government.[26]

Uncovered by the Chamber of Digital Commerce (an American non-profit advocacy group), their contents shed light on Beijing's mounting efforts to digitise the renminbi, which has sparked alarm in the West and spurred central bankers around the world to begin exploring similar projects.[26] Some commentators have said that the U.S., which has no current plans to issue a government-backed digital currency, risks falling behind China and risking its dominance in the global financial system.[27] Victor Shih, a China expert and professor at the University of California San Diego, said that merely introducing a digital currency "doesn't solve the problem that some people holding renminbi offshore will want to sell that renminbi and exchange it for the dollar", as the dollar is considered to be a safer asset.[28] Eswar Prasad, an economics professor at Cornell University, said that the digital renminbi "will hardly put a dent in the dollar's status as the dominant global reserve currency" due to the United States' "economic dominance, deep and liquid capital markets, and still-robust institutional framework".[28][29] The U.S. dollar's share as a reserve currency is above 60%, while that of the renminbi is about 2%.[28]

In April 2020, The Guardian reported that the digital currency e-RMB had been adopted into multiple cities' monetary systems and "some government employees and public servants receive their salaries in the digital currency from May. The Guardian quoted a China Daily report which stated "A sovereign digital currency provides a functional alternative to the dollar settlement system and blunts the impact of any sanctions or threats of exclusion both at a country and company level. It may also facilitate integration into globally traded currency markets with a reduced risk of politically inspired disruption."[30] There were talks of testing out the digital renminbi in the Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022, but China's overall timetable for rolling out the digital currency was unclear.[31]

Interest rate & Green bonds

In May 2023, RMB interest rate swaps was launched.[32] In June 2023, under the Government Green Bond Programme, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (HKSAR) announced a green bonds offering, of approximately US$6 billion denominated in USD, EUR and RMB.[32][33]

Issuance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

As of 2019, renminbi banknotes are available in denominations from ¥0.1, ¥0.5 (1 and 5 jiao), ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50 and ¥100. These denominations have been available since 1955, except for the ¥20 notes (added in 1999 with the fifth series) ¥50 and ¥100 notes (added in 1987 with the fourth series). Coins are available in denominations from ¥0.01 to ¥1 (¥0.01–1). Thus some denominations exist in both coins and banknotes. On rare occasions, larger yuan coin denominations such as ¥5 have been issued to commemorate events but use of these outside of collecting has never been widespread.

The denomination of each banknote is printed in simplified written Chinese. The numbers themselves are printed in financial[c] Chinese numeral characters, as well as Arabic numerals. The denomination and the words "People's Bank of China" are also printed in Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang on the back of each banknote, in addition to the boldface Hanyu Pinyin "Zhongguo Renmin Yinhang" (without tones). The right front of the note has a tactile representation of the denomination in Chinese Braille starting from the fourth series. See corresponding section for detailed information.

The fen and jiao denominations have become increasingly unnecessary as prices have increased. Coins under ¥0.1 are used infrequently. Chinese retailers tend to avoid fractional values (such as ¥9.99), opting instead to round to the nearest yuan (such as ¥9 or ¥10).[34]

Coins

In 1953, aluminium ¥0.01, ¥0.02, and ¥0.05 coins began being struck for circulation, and were first introduced in 1955. These depict the national emblem on the obverse (front) and the name and denomination framed by wheat stalks on the reverse (back). In 1980, brass ¥0.1, ¥0.2, and ¥0.5 and cupro-nickel ¥1 coins were added, although the ¥0.1 and ¥0.2 were only produced until 1981, with the last ¥0.5 and ¥1 issued in 1985. All jiǎo coins depicted similar designs to the fēn coins while the yuán depicted the Great Wall of China.

In 1991, a new coinage was introduced, consisting of an aluminium ¥0.1, brass ¥0.5 and nickel-clad steel ¥1. These were smaller than the previous jiǎo and yuán coins and depicted flowers on the obverse and the national emblem on the reverse. Issuance of the aluminium ¥0.01 and ¥0.02 coins ceased in 1991, with that of the ¥0.05 halting in 1994. The small coins were still struck for annual uncirculated mint sets in limited quantities, and from the beginning of 2005, the ¥0.01 coin got a new lease on life by being issued again every year since then up to present.

New designs of the ¥0.1, ¥0.5 (now brass-plated steel), and ¥1 (nickel-plated steel) were again introduced in between 1999 and 2002. The ¥0.1 was significantly reduced in size, and in 2005 its composition was changed from aluminium to more durable nickel-plated steel. An updated version of these coins was announced in 2019. While the overall design is unchanged, all coins including the ¥0.5 are now of nickel-plated steel, and the ¥1 coin was reduced in size.[35][36]

The frequency of usage of coins varies between different parts of China, with coins typically being more popular in urban areas (with 5-jiǎo and 1-yuán coins used in vending machines), and small notes being more popular in rural areas. Older fēn and large jiǎo coins are uncommonly still seen in circulation, but are still valid in exchange.

Banknotes

As of 2023, there have been five series of renminbi banknotes issued by the People's Republic of China:[37][38][39][40]

- The first series of renminbi banknotes was issued on 1 December 1948, by the newly founded People's Bank of China. It introduced notes in denominations of ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, ¥100 and ¥1,000 yuan. Notes for ¥200, ¥500, ¥5,000 and ¥10,000 followed in 1949, with ¥50,000 notes added in 1950. A total of 62 different designs were issued. The notes were officially withdrawn on various dates between 1 April and 10 May 1955. The name "first series" was given retroactively in 1950, after work began to design a new series.[16]

- These first renminbi notes were printed with the words "People's Bank of China", "Republic of China", and the denomination, written in Chinese characters by Dong Biwu.[41]

- The second series of renminbi banknotes was introduced on 1 March 1955 (but dated 1953). Each note has the words "People's Bank of China" as well as the denomination in the Uyghur, Tibetan, Mongolian and Zhuang languages on the back, which has since appeared in each series of renminbi notes. The denominations available in banknotes were ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05, ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥3, ¥5 and ¥10. Except for the three fen denominations and the ¥3 which were withdrawn, notes in these denominations continued to circulate. Good examples of this series have gained high status with banknote collectors.

- The third series of renminbi banknotes was introduced on 15 April 1962, though many denominations were dated 1960. New dates would be issued as stocks of older dates were gradually depleted. The sizes and design layout of the notes had changed but not the order of colours for each denomination. For the next two decades, the second and third series banknotes were used concurrently. The denominations were of ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5 and ¥10. The third series was phased out during the 1990s and then was recalled completely on 1 July 2000.

- The fourth series of renminbi banknotes was introduced between 1987 and 1997, although the banknotes were dated 1980, 1990, or 1996. They were withdrawn from circulation on 1 May 2019. Banknotes are available in denominations of ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5, ¥10, ¥50 and ¥100. Like previous issues, the colour designation for already existing denominations remained in effect. The second to fourth series of renminbi banknotes were designed by professors at the Central Academy of Art including Luo Gongliu and Zhou Lingzhao.

- The fifth series of renminbi banknotes and coins was progressively introduced from its introduction in 1999. This series also bears the issue years 2005 (all except ¥1), 2015 (¥100 only) and 2019 (¥1, ¥10, ¥20 and ¥50). As of 2019, it includes banknotes for ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50 and ¥100. Significantly, the fifth series uses the portrait of Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong on all banknotes, in place of the various leaders, workers and representations of China's ethnic groups which had been featured previously. During this series new security features were added, the ¥2 denomination was discontinued, the colour pattern for each note was changed and a new denomination of ¥20 was introduced for this series. A revised series of coins of ¥0.1, ¥0.5 and ¥1 and banknotes of ¥1, ¥10, ¥20 and ¥50 were issued for general circulation on 30 August 2019. The ¥5 banknote of the fifth series was issued in November 2020 with new printing technology in a bid to reduce counterfeiting of Chinese currency.

Commemorative issues of the renminbi banknotes

In 1999, a commemorative red ¥50 note was issued in honour of the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the People's Republic of China. This note features Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong on the front and various animals on the back.

An orange polymer note, commemorating the new millennium was issued in 2000 with a face value of ¥100. This features a dragon on the obverse and the reverse features the China Millennium monument (at the Center for Cultural and Scientific Fairs).

For the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a green ¥10 note was issued featuring the Bird's Nest Stadium on the front with the back showing a classical Olympic discus thrower and various other athletes.

On 26 November 2015, the People's Bank of China issued a blue ¥100 commemorative note to commemorate aerospace science and technology.[42][43]

In commemoration of the 70th Anniversary of the issuance of the Renminbi, the People's Bank of China issued 120 million ¥50 banknotes on 28 December 2018.

In commemoration of the 2022 Winter Olympics, the People's Bank of China issued ¥20 commemorative banknotes in both paper and polymer in December 2021.

In commemoration of the 2024 Chinese New Year, the People's Bank of China issued ¥20 commemorative banknotes in polymer in January 2024.

Use in ethnic minority regions of China

The renminbi yuan has different names when used in ethnic minority regions of China.

- When used in Inner Mongolia and other Mongol autonomies, a yuan is called a tugreg (Mongolian: ᠲᠦᠭᠦᠷᠢᠭ᠌, төгрөг tügürig). However, when used in the republic of Mongolia, it is still named yuani (Mongolian: юань) to differentiate it from Mongolian tögrög (Mongolian: төгрөг). One Chinese tügürig (tugreg) is divided into 100 mönggü (Mongolian: ᠮᠥᠩᠭᠦ, мөнгө), one Chinese jiao is labeled "10 mönggü". In Mongolian, renminbi is called aradin jogos or arad-un jogos (Mongolian: ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠨ ᠵᠣᠭᠣᠰ, ардын зоос arad-un ǰoγos).

- When used in Tibet and other Tibetan autonomies, a yuan is called a gor (Tibetan: སྒོར་, ZYPY: Gor). One gor is divided into 10 gorsur (Tibetan: སྒོར་ཟུར་, ZYPY: Gorsur) or 100 gar (Tibetan: སྐར་, ZYPY: gar). In Tibetan, renminbi is called mimangxogngü (Tibetan: མི་དམངས་ཤོག་དངུལ།, ZYPY: Mimang Xogngü) or mimang shog ngul.

- When used in the Uyghur autonomous region of Xinjiang, the renminbi is called Xelq puli (Uyghur: خەلق پۇلى)

Production and minting

Renminbi currency production is carried out by a state owned corporation, China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation (CBPMC; 中国印钞造币总公司) headquartered in Beijing.[44] CBPMC uses several printing, engraving and minting facilities around the country to produce banknotes and coins for subsequent distribution. Banknote printing facilities are based in Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Xi'an, Shijiazhuang, and Nanchang. Mints are located in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Shenyang. Also, high grade paper for the banknotes is produced at two facilities in Baoding and Kunshan. The Baoding facility is the largest facility in the world dedicated to developing banknote material according to its website.[45] In addition, the People's Bank of China has its own printing technology research division that researches new techniques for creating banknotes and making counterfeiting more difficult.

Suggested future designedit

On 13 March 2006, some delegates to an advisory body at the National People's Congress proposed to include Sun Yat-sen and Deng Xiaoping on the renminbi banknotes. However, the proposal was not adopted.[46]

Economicsedit

Valueedit

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code |

Symbol or abbreviation |

Proportion of daily volume | Change (2019–2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2019 | April 2022 | |||||

| 1 | U.S. dollar | USD | US$ | 88.3% | 88.5% | |

| 2 | Euro | EUR | € | 32.3% | 30.5% | |

| 3 | Japanese yen | JPY | ¥ / 円 | 16.8% | 16.7% | |

| 4 | Sterling | GBP | £ | 12.8% | 12.9% | |

| 5 | Renminbi | CNY | ¥ / 元 | 4.3% | 7.0% | |

| 6 | Australian dollar | AUD | A$ | 6.8% | 6.4% | |

| 7 | Canadian dollar | CAD | C$ | 5.0% | 6.2% | |

| 8 | Swiss franc | CHF | CHF | 4.9% | 5.2% | |

| 9 | Hong Kong dollar | HKD | HK$ | 3.5% | 2.6% | |

| 10 | Singapore dollar | SGD | S$ | 1.8% | 2.4% | |

| 11 | Swedish krona | SEK | kr | 2.0% | 2.2% | |

| 12 | South Korean won | KRW | ₩ / 원 | 2.0% | 1.9% | |

| 13 | Norwegian krone | NOK | kr | 1.8% | 1.7% | |

| 14 | New Zealand dollar | NZD | NZ$ | 2.1% | 1.7% | |

| 15 | Indian rupee | INR | ₹ | 1.7% | 1.6% | |

| 16 | Mexican peso | MXN | MX$ | 1.7% | 1.5% | |

| 17 | New Taiwan dollar | TWD | NT$ | 0.9% | 1.1% | |

| 18 | South African rand | ZAR | R | 1.1% | 1.0% | |

| 19 | Brazilian real | BRL | R$ | 1.1% | 0.9% | |

| 20 | Danish krone | DKK | kr | 0.6% | 0.7% | |

| 21 | Polish złoty | PLN | zł | 0.6% | 0.7% | |

| 22 | Thai baht | THB | ฿ | 0.5% | 0.4% | |

| 23 | Israeli new shekel | ILS | ₪ | 0.3% | 0.4% | |

| 24 | Indonesian rupiah | IDR | Rp | 0.4% | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Chinese_Yuan||