A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

In the politics of the United States, elections are held for government officials at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, the nation's head of state, the president, is elected indirectly by the people of each state, through an Electoral College. Today, these electors almost always vote with the popular vote of their state. All members of the federal legislature, the Congress, are directly elected by the people of each state. There are many elected offices at state level, each state having at least an elective governor and legislature. There are also elected offices at the local level, in counties, cities, towns, townships, boroughs, and villages; as well as for special districts and school districts which may transcend county and municipal boundaries.

The country's election system is highly decentralized.[1] While the U.S. Constitution does set parameters for the election of federal officials, state law, not federal, regulates most aspects of elections in the U.S., including primary elections, the eligibility of voters (beyond the basic constitutional definition), the running of each state's electoral college, as well as the running of state and local elections. All elections—federal, state, and local—are administered by the individual states,[2] with many aspects of the system's operations delegated to the county or local level.[1]

Under federal law, the general elections of the president and Congress occur on Election Day, the Tuesday after the first Monday of November. These federal general elections are held in even-numbered years, with presidential elections occurring every four years, and congressional elections occurring every two years. The general elections that are held two years after the presidential ones are referred to as the midterm elections. General elections for state and local offices are held at the discretion of the individual state and local governments, with many of these races coinciding with either presidential or midterm elections as a matter of convenience and cost saving, while other state and local races may occur during odd-numbered "off years". The date when primary elections for federal, state, and local races occur are also at the discretion of the individual state and local governments; presidential primaries in particular have historically been staggered between the states, beginning sometime in January or February, and ending about mid-June before the November general election.

The restriction and extension of voting rights to different groups has been a contested process throughout United States history. The federal government has also been involved in attempts to increase voter turnout, by measures such as the National Voter Registration Act of 1993. The financing of elections has also long been controversial, because private sources make up substantial amounts of campaign contributions, especially in federal elections. Voluntary public funding for candidates willing to accept spending limits was introduced in 1974 for presidential primaries and elections. The Federal Elections Commission, created in 1975 by an amendment to the Federal Election Campaign Act, has the responsibility to disclose campaign finance information, to enforce the provisions of the law such as the limits and prohibitions on contributions, and to oversee the public funding of U.S. presidential elections.

Voting

Voting methods

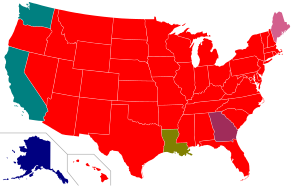

Voting systems used in each state:

The most common method used in U.S. elections is the first-past-the-post system, where the highest-polling candidate wins the election.[3] Under this system, a candidate only requires a plurality of votes to win, rather than an outright majority. Some may use a two-round system, where if no candidate receives a required number of votes (usually but not always a majority) then there is a runoff between the two candidates with the most votes.[citation needed]

Since 2002, several cities have adopted instant-runoff voting in their elections. Voters rank the candidates in order of preference rather than voting for a single candidate. If a candidate secures more than half of votes cast, that candidate wins. Otherwise, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Ballots assigned to the eliminated candidate are recounted and assigned to those of the remaining candidates who rank next in order of preference on each ballot. This process continues until one candidate wins by obtaining more than half the votes.[citation needed] In 2016, Maine became the first state to adopt instant-runoff voting (known in the state as ranked-choice voting) statewide for its elections, although due to state constitutional provisions, the system is only used for federal elections and state primaries.

Eligibility

The eligibility of an individual for voting is set out in the constitution and also regulated at state level. The constitution states that suffrage cannot be denied on grounds of race or color, sex, or age for citizens eighteen years or older. Beyond these basic qualifications, it is the responsibility of state legislatures to regulate voter eligibility. Some states ban convicted criminals, especially felons, from voting for a fixed period of time or indefinitely.[4] The number of American adults who are currently or permanently ineligible to vote due to felony convictions is estimated to be 5.3 million.[5] Some states also have legacy constitutional statements barring those legally declared incompetent from voting; such references are generally considered obsolete and are being considered for review or removal where they appear.[6]

About 4.3 million American citizens that reside in Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories do not have the same level of federal representation as those that reside in the 50 U.S. states. These areas only have non-voting members in the U.S. House of Representatives and no representation in the U.S. Senate. Citizens in the U.S. territories are also not represented in the Electoral College and therefore cannot vote for the president.[7] Those in Washington, D.C. are permitted to vote for the president because of the Twenty-third Amendment.

Noncitizen voting

Federal law prohibits noncitizens from voting in federal elections.[8]

As of 2023, 8 state constitutions specifically state that "only" a citizen can vote in an election: Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, North Dakota, and Ohio.[9]

Voter registration

While the federal government has jurisdiction over federal elections, most election laws are decided at the state level. All U.S. states except North Dakota require that citizens who wish to vote be registered. In many states, voter registration takes place at the county or municipal level. Traditionally, voters had to register directly at state or local offices to vote, but in the mid-1990s, efforts were made by the federal government to make registering easier, in an attempt to increase turnout. The National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (the "Motor Voter" law) required state governments that receive certain types of federal funding to make the voter registration process easier by providing uniform registration services through drivers' license registration centers, disability centers, schools, libraries, and mail-in registration. Other states allow citizens same-day registration on Election Day.

An estimated 50 million Americans are unregistered. It has been reported that registering to vote poses greater obstacles for low-income citizens, racial minorities and linguistic minorities, Native Americans, and persons with disabilities. International election observers have called on authorities in the U.S. to implement measures to remediate the high number of unregistered citizens.[10]

In many states, citizens registering to vote may declare an affiliation with a political party.[11] This declaration of affiliation does not cost money, and does not make the citizen a dues-paying member of a party. A party cannot prevent a voter from declaring his or her affiliation with them, but it can refuse requests for full membership. In some states, only voters affiliated with a party may vote in that party's primary elections (see below). Declaring a party affiliation is never required. Some states, including Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Washington, practice non-partisan registration.[12]

Voter ID laws

Voter ID laws in the United States are laws that require a person to provide some form of official identification before they are permitted to register to vote, receive a ballot for an election, or to actually vote in elections in the United States.

Proponents of voter ID laws argue that they reduce electoral fraud while placing only little burden on voters.

Absentee and mail voting

Voters unable or unwilling to vote at polling stations on Election Day may vote via absentee ballots, depending on state law. Originally these ballots were for people who could not go to the polling place on election day. Now some states let them be used for convenience, but state laws still call them absentee ballots.[13] Absentee ballots can be sent and returned by mail, or requested and submitted in person, or dropped off in locked boxes. About half the states and territories allow "no excuse absentee," where no reason is required to request an absentee ballot; others require a valid reason, such as infirmity or travel.[13] Some states let voters with permanent disabilities apply for permanent absentee voter status, and some other states let all citizens apply for permanent status, so they will automatically receive an absentee ballot for each election.[14] Otherwise a voter must request an absentee ballot before the election occurs.

In Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington state, all ballots are delivered through the mail; in many other states there are counties or certain small elections where everyone votes by mail.[13][15]

As of July 2020, 26 states allow designated agents to collect and submit ballots on behalf of another voter, whose identities are specified on a signed application. Usually such agents are family members or persons from the same residence. 13 states neither enable nor prohibit ballot collection as a matter of law. Among those that allow it, 12 have limits on how many ballots an agent may collect.

Americans living outside the United States, including active duty members of the armed forces stationed outside of their state of residency, may register and vote under the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA). Almost half the states require these ballots to be returned by mail. Other states allow mail along with some combination of fax, or email; four states allow a web portal.[16]

A significant measure to prevent some types of fraud has been to require the voter's signature on the outer envelope, which is compared to one or more signatures on file before taking the ballot out of the envelope and counting it.[17] Not all states have standards for signature review.[18] There have been concerns that signatures are improperly rejected from young and minority voters at higher rates than others, with no or limited ability of voters to appeal the rejection.[19][20] For other types of errors, experts estimate that while there is more fraud with absentee ballots than in-person voting, it has affected only a few local elections.[21][22]

Following the 2020 United States presidential election, amidst disputes of its outcome, as a rationale behind litigation demanding a halt to official vote counting in some areas, allegations were made that vote counting is offshored. Former Trump Administration official Chris Krebs, head of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) during the election, said in a December 2020 interview that, "All votes in the United States of America are counted in the United States of America."[23]

One documented trend is that in-person votes and early votes are more likely to lean to the Republican Party, while the provisional ballots, which are counted later, trend to the Democratic Party. This phenomenon is known as blue shift, and has led to situations where Republicans won on election night only to be overtaken by Democrats after all votes were counted.[24] Foley[clarification needed] did not find that mail-in or absentee votes favored either party.[25]

Early voting

Early voting is a formal process where voters can cast their ballots prior to the official Election Day. Early voting in person is allowed in 33 states and in Washington, D.C., with no excuse required.[26]

Voting equipment

| Voting technology | 1980 prevalence | 2008 prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Hand-counted paper ballot | 10% | < 1% |

| Lever machine | 40% | 6% |

| Punch card | ~33% | negligible |

| Optical scan | 2% | 60% |

| DRE | < 1% | ~33–38% |

The earliest voting in the US was through paper ballots that were hand-counted. By the late 1800s, paper ballots printed by election officials were nearly universal. By 1980, 10% of American voters used paper ballots that were counted by hand, which dropped below 1% by 2008.[27]

Mechanical voting machines were first used in the US in the 1892 elections in Lockport, New York. The state of Massachusetts was one of the first states to adopt lever voting machines, doing so in 1899, but the state's Supreme Judicial Court ruled their usage unconstitutional in 1907. Lever machines grew in popularity despite controversies, with about two-thirds of votes for president in the 1964 United States presidential election cast with lever machines. Lever machine use declined to about 40% of votes in 1980, then 6% in 2008. Punch card voting equipment was developed in the 1960s, with about one-third of votes cast with punch cards in 1980. New York was the last state to phase out lever voting in response to the 2000 Help America Vote Act (HAVA), which allocated funds for the replacement of lever machine and punch card voting equipment. New York replaced its lever voting with optical scanning in 2010.[27]

In the 1960s, technology was developed that enabled paper ballots filled with pencil or ink to be optically scanned rather than hand-counted. In 1980, about 2% of votes used optical scanning; this increased to 30% by 2000 and 60% by 2008. In the 1970s, the final major voting technology for the US was developed, the DRE voting machine. In 1980, less than 1% of ballots were cast with DRE. Prevalence grew to 10% in 2000, then peaked at 38% in 2006. Because DREs are fully digital, with no paper trail of votes, backlash against them caused prevalence to drop to 33% in 2010.[27]

The voting equipment used by a given US county is related to the county's historical wealth. A county's use of punch cards in the year 2000 was positively correlated with the county's wealth in 1969, when punch card machines were at their peak of popularity. Counties with higher wealth in 1989 were less likely to still use punch cards in 2000. This supports the idea that punch cards were used in counties that were well-off in the 1960s, but whose wealth declined in the proceeding decades. Counties that maintained their wealth from the 1960s onwards could afford to replace punch card machines as they fell out of favor.[27]

Levels of election

Federal elections

The United States has a presidential system of government, which means that the executive and legislature are elected separately. Article II of the United States Constitution requires that the election of the U.S. president by the Electoral College must occur on a single day throughout the country; Article I established that elections for Congressional offices, however, can be held at different times. Congressional and presidential elections take place simultaneously every four years, and the intervening Congressional elections, which take place every two years, are called midterm elections.

The constitution states that members of the United States House of Representatives must be at least 25 years old, a citizen of the United States for at least seven years, and be a (legal) inhabitant of the state they represent. Senators must be at least 30 years old, a citizen of the United States for at least nine years, and be a (legal) inhabitant of the state they represent.[28] The president and vice president must be at least 35 years old, a natural born citizen of the United States, and a resident in the United States for at least fourteen years.[29] It is the responsibility of state legislatures to regulate the qualifications for a candidate appearing on a ballot paper,[30] although in order to get onto the ballot, a candidate must often collect a legally defined number of signatures or meet other state-specific requirements.[31]

Presidential elections

The president and the vice president are elected together in a presidential election.[32] It is an indirect election, with the winner being determined by votes cast by electors of the Electoral College. In modern times, voters in each state select a slate of electors from a list of several slates designated by different parties or candidates, and the electors typically promise in advance to vote for the candidates of their party (whose names of the presidential candidates usually appear on the ballot rather than those of the individual electors). The winner of the election is the candidate with at least 270 Electoral College votes.[33] It is possible for a candidate to win the electoral vote, and lose the (nationwide) popular vote (receive fewer votes nationwide than the second ranked candidate). This has occurred five times in US history: in 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.[34] Prior to ratification of the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1804), the runner-up in a presidential election[35] became the vice president.

Electoral College votes are cast by individual states by a group of electors; each elector casts one electoral college vote. Until the Twenty-third Amendment to the United States Constitution of 1961, citizens from the District of Columbia did not have representation and/or electors in the electoral college. In modern times, with electors usually committed to vote for a party candidate in advance, electors that vote against the popular vote in their state are called faithless electors, and occurrences are rare. State law regulates how states cast their electoral college votes. In all states except Maine and Nebraska, the candidate that wins the most votes in the state receives all its electoral college votes (a "winner takes all" system).[36] From 1972 in Maine, and from 1996 in Nebraska, two electoral votes are awarded based on the winner of the statewide election, and the rest (two in Maine and three in Nebraska) go to the highest vote-winner in each of the state's congressional districts.[37]