A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| |

| Headquarters | Ostend district, Frankfurt, Germany |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°06′32″N 8°42′12″E / 50.1089°N 8.7034°E |

| Established | 1 June 1998 |

| Governing body | |

| Key people |

|

| Currency | Euro (€) EUR (ISO 4217) |

| Reserves | €526 billion

|

| Bank rate | 4.25% (Main refinancing operations)[1] 4.50% (Marginal lending facility)[1] |

| Interest on reserves | 3.75% (Deposit facility)[1] |

| Preceded by | 20 central banks

|

| Website | ecb.europa.eu |

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the central component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union.[2] It is one of the world's most important central banks.

The ECB Governing Council makes monetary policy for the Eurozone and the European Union, administers the foreign exchange reserves of EU member states, engages in foreign exchange operations, and defines the intermediate monetary objectives and key interest rate of the EU. The ECB Executive Board enforces the policies and decisions of the Governing Council, and may direct the national central banks when doing so.[3] The ECB has the exclusive right to authorise the issuance of euro banknotes. Member states can issue euro coins, but the volume must be approved by the ECB beforehand. The bank also operates the TARGET2 payments system.

The ECB was established by the Treaty of Amsterdam in May 1999 with the purpose of guaranteeing and maintaining price stability. On 1 December 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon became effective and the bank gained the official status of an EU institution. When the ECB was created, it covered a Eurozone of eleven members. Since then, Greece joined in January 2001, Slovenia in January 2007, Cyprus and Malta in January 2008, Slovakia in January 2009, Estonia in January 2011, Latvia in January 2014, Lithuania in January 2015 and Croatia in January 2023.[4] The current President of the ECB is Christine Lagarde. Seated in Frankfurt, Germany, the bank formerly occupied the Eurotower prior to the construction of its new seat.

The ECB is directly governed by European Union law. Its capital stock, worth €11 billion, is owned by all 27 central banks of the EU member states as shareholders.[5] The initial capital allocation key was determined in 1998 on the basis of the states' population and GDP, but the capital key has been readjusted since.[5] Shares in the ECB are not transferable and cannot be used as collateral.

History

Early years (1998–2007)

The European Central Bank is the de facto successor of the European Monetary Institute (EMI).[6] The EMI was established at the start of the second stage of the EU's Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) to handle the transitional issues of states adopting the euro and prepare for the creation of the ECB and European System of Central Banks (ESCB).[6] The EMI itself took over from the earlier European Monetary Cooperation Fund (EMCF).[4]

The ECB formally replaced the EMI on 1 June 1998 by virtue of the Treaty on European Union (TEU, Treaty of Maastricht), however it did not exercise its full powers until the introduction of the euro on 1 January 1999, signalling the third stage of EMU.[6] The bank was the final institution needed for EMU, as outlined by the EMU reports of Pierre Werner and President Jacques Delors. It was established on 1 June 1998 The first President of the Bank was Wim Duisenberg, the former president of the Dutch central bank and the European Monetary Institute.[7] While Duisenberg had been the head of the EMI (taking over from Alexandre Lamfalussy of Belgium) just before the ECB came into existence,[7] the French government wanted Jean-Claude Trichet, former head of the French central bank, to be the ECB's first president.[7] The French argued that since the ECB was to be located in Germany, its president should be French. This was opposed by the German, Dutch and Belgian governments who saw Duisenberg as a guarantor of a strong euro.[8] Tensions were abated by a gentleman's agreement in which Duisenberg would stand down before the end of his mandate, to be replaced by Trichet.[9]

Trichet replaced Duisenberg as president in November 2003. Until 2007, the ECB had very successfully managed to maintain inflation close but below 2%.

Response to the financial crises (2008–2014)

The European Central Bank underwent through a deep internal transformation as it faced the global financial crisis and the Eurozone debt crisis.

This section needs expansion with: here we need some headline facts on the early response to the Lehman shock: interest cuts, repos & swap lines, securitized bond purchases…. You can help by adding to it. (April 2021) |

Early response to the Eurozone debt crisis

The so-called European debt crisis began after Greece's new elected government uncovered the real level indebtedness and budget deficit and warned EU institutions of the imminent danger of a Greek sovereign default.

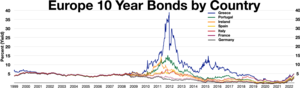

Foreseeing a possible sovereign default in the eurozone, the general public, international and European institutions, and the financial community reassessed the economic situation and creditworthiness of some Eurozone member states. Consequently, sovereign bonds yields of several Eurozone countries started to rise sharply. This provoked a self-fulfilling panic on financial markets: the more Greek bonds yields rose, the more likely a default became possible, the more bond yields increased in turn.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

This panic was also aggravated because of the reluctance of the ECB to react and intervene on sovereign bond markets for two reasons. First, because the ECB's legal framework normally forbids the purchase of sovereign bonds in the primary market (Article 123. TFEU),[17] An over-interpretation of this limitation, inhibited the ECB from implementing quantitative easing like the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England did as soon as 2008, which played an important role in stabilizing markets.

Secondly, a decision by the ECB made in 2005 introduced a minimum credit rating (BBB-) for all Eurozone sovereign bonds to be eligible as collateral to the ECB's open market operations. This meant that if a private rating agencies were to downgrade a sovereign bond below that threshold, many banks would suddenly become illiquid because they would lose access to ECB refinancing operations. According to former member of the governing council of the ECB Athanasios Orphanides, this change in the ECB's collateral framework "planted the seed" of the euro crisis.[18]

Faced with those regulatory constraints, the ECB led by Jean-Claude Trichet in 2010 was reluctant to intervene to calm down financial markets. Up until 6 May 2010, Trichet formally denied at several press conferences[19] the possibility of the ECB to embark into sovereign bonds purchases, even though Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy faced waves of credit rating downgrades and increasing interest rate spreads.

Market interventions (2010–2011)

In a remarkable u-turn, the ECB announced on 10 May 2010,[20] the launch of a "Securities Market Programme" (SMP) which involved the discretionary purchase of sovereign bonds in secondary markets. Extraordinarily, the decision was taken by the Governing Council during a teleconference call only three days after the ECB's usual meeting of 6 May (when Trichet still denied the possibility of purchasing sovereign bonds). The ECB justified this decision by the necessity to "address severe tensions in financial markets." The decision also coincided with the EU leaders decision of 10 May to establish the European Financial Stabilisation mechanism, which would serve as a crisis fighting fund to safeguard the euro area from future sovereign debt crisis.[21]

Although at first limited to the debt of Greece, Ireland and Portugal, the bulk of the ECB's bond buying eventually consisted of Spanish and Italian debt.[22] These purchases were intended to dampen international speculation against stressed countries, and thus avoid a contagion of the Greek crisis towards other Eurozone countries. The assumption—largely justified—was that speculative activity would decrease over time and the value of the assets increase.

Although SMP purchases did inject liquidity into financial markets, all of these injections were "sterilized" through weekly liquidity absorption. So the operation was net neutral in liquidity terms (though this was of little practical importance since normal monetary policy operations were ensuring unlimited supplies of liquidity at the main policy interest rate).[23][citation needed][24]

In September 2011, ECB's Board member Jürgen Stark, resigned in protest against the "Securities Market Programme" which involved the purchase of sovereign bonds from Southern member states, a move that he considered as equivalent to monetary financing, which is prohibited by the EU Treaty. The Financial Times Deutschland referred to this episode as "the end of the ECB as we know it", referring to its hitherto perceived "hawkish" stance on inflation and its historical Deutsche Bundesbank influence.[25]

As of 18 June 2012, the ECB in total had spent €212.1bn (equal to 2.2% of the Eurozone GDP) for bond purchases covering outright debt, as part of the Securities Markets Programme.[26] Controversially, the ECB made substantial profits out of SMP, which were largely redistributed to Eurozone countries.[27][28] In 2013, the Eurogroup decided to refund those profits to Greece, however, the payments were suspended from 2014 until 2017 over the conflict between Yanis Varoufakis and ministers of the Eurogroup. In 2018, profits refunds were reinstalled by the Eurogroup. However, several NGOs complained that a substantial part of the ECB profits would never be refunded to Greece.[29]

Role in the Troika (2010–2015)

The ECB played a controversial role in the "Troika" by rejecting most forms of debt restructuring of public and bank debts,[30] and pressing governments to adopt bailout programmes and structural reforms through secret letters to Italian, Spanish, Greek and Irish governments. It has further been accused of interfering in the Greek referendum of July 2015 by constraining liquidity to Greek commercial banks.[31]

This section needs expansion with: explanations on the role of ECB for Greece, Italy, Spain, Cyprus, Portugal.. You can help by adding to it. (April 2021) |

In November 2010, reflecting the huge increase in borrowing, including the cover the cost of having guaranteed the liabilities of banks, the cost of borrowing in the private financial markets had become prohibitive for the Irish government. Although it had deferred the cash cost of recapitalising the failing Anglo Irish Bank by nationalising it and issuing it with a "promissory note" (an IOU), the Government also faced a large deficit on its non-banking activities, and it therefore turned to the official sector for a loan to bridge the shortfall until its finances were credibly back on a sustainable footing. (Meanwhile, Anglo used the promissory note as collateral for its emergency loan (ELA) from the Central Bank. This enabled Anglo was able to repay its depositors and bondholders.

It became clear later that the ECB played a key role in making sure the Irish government did not let Anglo default on its debts, to avoid financial instability risks. On 15 October and 6 November 2010, the ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet sent two secret letters[32] to the Irish finance Minister which essentially informed the Irish government of the possible suspension of ELA's credit lines, unless the government requested a financial assistance programme to the Eurogroup under the condition of further reforms and fiscal consolidation.

In addition, the ECB insisted that no debt restructuring (or bail-in) should be applied to the nationalized banks' bondholders, a measure which could have saved Ireland 8 billion euros.[33]

During 2012, the ECB pressed for an early end to the ELA, and this situation was resolved with the liquidation of the successor institution IBRC in February 2013. The promissory note was exchanged for much longer term marketable floating rate notes which were disposed of by the Central Bank over the following decade.

In April 2011, the ECB raised interest rates for the first time since 2008 from 1% to 1.25%,[34] with a further increase to 1.50% in July 2011.[35] However, in 2012–2013 the ECB sharply lowered interest rates to encourage economic growth, reaching the historically low 0.25% in November 2013.[1] Soon after the rates were cut to 0.15%, then on 4 September 2014 the central bank reduced the rates by two-thirds from 0.15% to 0.05%.[36] Recently, the interest rates were further reduced reaching 0.00%, the lowest rates on record.[1]

In a report adopted on 13 March 2014, the European Parliament criticized the "potential conflict of interest between the current role of the ECB in the Troika as 'technical advisor' and its position as a creditor of the four Member States, as well as its mandate under the Treaty". The report was led by Austrian right-wing MEP Othmar Karas and French Socialist MEP Liem Hoang Ngoc.

Response under Mario Draghi (2012–2015)

On 1 November 2011, Mario Draghi replaced Jean-Claude Trichet as President of the ECB.[37] This change in leadership also marks the start of a new era under which the ECB will become more and more interventionist and eventually ended the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

Draghi's presidency started with the impressive launch of a new round of 1% interest loans with a term of three years (36 months) – the Long-term Refinancing operations (LTRO). Under this programme, 523 Banks tapped as much as €489.2 bn (US$640 bn). Observers were surprised by the volume of loans made when it was implemented.[38][39][40] By far biggest amount of €325bn was tapped by banks in Greece, Ireland, Italy and Spain.[41] Although those LTROs loans did not directly benefit EU governments, it effectively allowed banks to do a carry trade, by lending off the LTROs loans to governments with an interest margin. The operation also facilitated the rollover of €200bn of maturing bank debts[42] in the first three months of 2012.

"Whatever it takes" (26 July 2012)

Facing renewed fears about sovereigns in the eurozone continued Mario Draghi made a decisive speech in London, by declaring that the ECB "...is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the Euro. And believe me, it will be enough."[43] In light of slow political progress on solving the eurozone crisis, Draghi's statement has been seen as a key turning point in the eurozone crisis, as it was immediately welcomed by European leaders, and led to a steady decline in bond yields for eurozone countries, in particular Spain, Italy and France.[44][45]

Following up on Draghi's speech, on 6 September 2012 the ECB announced the Outright Monetary Transactions programme (OMT).[46] Unlike the previous SMP programme, OMT has no ex-ante time or size limit.[47] However, the activation of the purchases remains conditioned to the adherence by the benefitting country to an adjustment programme to the ESM. The program was adopted with near unanimity, the Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann being the sole member of the ECB's Governing Council to vote against it.[48]

Even if OMT was never actually implemented until today, it made the "Whatever it takes" pledge credible and significantly contributed to stabilizing financial markets and ending the sovereign debt crisis. According to various sources, the OMT programme and "whatever it takes" speeches were made possible because EU leaders previously agreed to build the banking union.[49]

Low inflation and quantitative easing (2015–2019)

In November 2014, the bank moved into its new premises, while the Eurotower building was dedicated to hosting the newly established supervisory activities of the ECB under European Banking Supervision.[50]

Although the sovereign debt crisis was almost solved by 2014, the ECB started to face a repeated decline[51] in the Eurozone inflation rate, indicating that the economy was going towards a deflation. Responding to this threat, the ECB announced on 4 September 2014 the launch of two bond buying purchases programmes: the Covered Bond Purchasing Programme (CBPP3) and Asset-Backed Securities Programme (ABSPP).[52]

On 22 January 2015, the ECB announced an extension of those programmes within a full-fledge "quantitative easing" programme which also included sovereign bonds, to the tune of 60 billion euros per month up until at least September 2016. The programme was started on 9 March 2015.[53]

On 8 June 2016, the ECB added corporate bonds to its asset purchases portfolio with the launch of the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP).[54] Under this programme, it conducted the net purchase of corporate bonds until January 2019 to reach about €177 billion. While the programme was halted for 11 months in January 2019, the ECB restarted net purchases in November 2019.[55]

As of 2021,[update] the size of the ECB's quantitative easing programme had reached 2947 billion euros.[56]

Long Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO)

The long term refinancing operations (LTRO) are regular open market operations providing financing to credit institutions for periods up to four years. They aim at favoring lending conditions to the private sector and more generally stimulating bank lending to the real economy,[57] thereby fostering growth.

In December 2011 and January 2012, in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, the ECB implemented two LTROs, injecting over €1000 billions of liquidity in the Eurozone financial system. They were later criticized for their inability to revive growth and to help truly revive the real economy, despite having stabilized the Eurozone’s financial institutions.[58] Further, these operations were devoid of monitoring from the ECB regarding the use made of these liquidities[58] and it appeared that banks had significantly used these funds to pursue carry-trade strategies,[59] purchasing sovereign bonds with higher rates and corresponding maturity to generate profits, instead of increasing private lending.[58][60]

These critics and deficiencies brought the ECB to instigate targeted long term refinancing operations (TLTROs), first in September and later in December 2014.[61] These complementary programs imposed conditionality on the LTROs.[58] The TLTROs provided low cost financing to participating banks, under the condition that they reached certain targets in terms of lending to firms and households.[60] The participating banks were thus more incited to lend to the real economy. A third wave of TLTRO’s was announced on 7 March 2019, namely the TLTRO III.[62][63]

Christine Lagarde's era (2019– )

In July 2019, EU leaders nominated Christine Lagarde to replace Mario Draghi as ECB President. Lagarde resigned from her position as managing director of the International Monetary Fund in July 2019[64] and formally took over the ECB's presidency on 1 November 2019.[65]

Lagarde immediately signalled a change of style in the ECB's leadership. She embarked the ECB on a strategic review of the ECB's monetary policy strategy, an exercise the ECB had not done for 17 years. As part of this exercise, Lagarde committed the ECB to look into how monetary policy could contribute to address climate change,[66] and promised that "no stone would be left unturned." The ECB president also adopted a change of communication style, in particular in her use of social media to promote gender equality,[67] and by opening dialogue with civil society stakeholders.[68][69]

COVID-19

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated an unprecedented crisis, profoundly impacting global public health, economies, and societal structures on an unparalleled scale. The COVID-19 crisis stands in contrast to the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis as it represents an exogenous shock to the real economy,[70] stemming from measures implemented to mitigate the public health emergency, distinct from the internal financial origins of the preceding crisis that transposed repercussions onto the real economy.[71] Following the measures implemented by all governments to counter the spread of COVID-19 across Europe, investors fled to safety,[72] which caused the risk of fire sales in asset markets, illiquidity spirals, credit spikes and discontinuities associated with market freezes.[73][74] The flight-to-safety also encouraged the fear that after the COVID-19 crisis was over, the stronger economies would emerge even stronger, while the weak economies would get even weaker.[75] Thanks to the more stringent banking regulations implemented after the Global Financial Crisis, a financial crisis was avoided as banks could cope better with the crisis and complementary measures were taken by the EU and national governments.[76]

Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP)

The Pandemic Asset Purchase Programme (PEPP) is an asset purchase programme initiated by the ECB to counter the detrimental effects to the Euro Area economy caused by the COVID-19 crisis.

To counter the COVID-19 crisis the ECB has established the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), in which the ECB is able to purchase securities from the private and public sector in a flexible manner,[77][78][79] with the purpose to prevent sovereign debt spreads to reach the same levels as during the European debt crisis.[75] It is a quantitative easing unconventional monetary policy,[80][81][82] based on the principles of the Asset Purchases Program (APP)[72] which is a similar programme established by the ECB in mid-2014.[83] Asset purchase programmes are intended to bring down risk premia or term premia.[84][85] However, the PEPP is not entirely the same as the APP, as it can deviate from the capital key strategy followed by the APP.[76][86][87][88][89][90] Second, the PEPP-envelope does not need to be used in full.[91] The PEPP is established as a separate purchase programme from and in addition to the APP with the sole purpose to respond to the economic and financial consequences of the COVID-19 crisis.[92][93][94] Following Philip R. Lane, chief economist of the ECB, the PEPP plays a dual role in the COVID-19 crisis: (i) ensuring price stability and at the same time (ii) stabilizing the market using the flexibility of the programme[73][95] to prevent market fragmentation.[71][72][96][97] National central banks are the main purchasers of the bonds under the principle of risk sharing: private bonds fall completely under the risk of national central banks, while only 20% of public bonds are subject to risk sharing.[98] These purchases under the PEPP eventually follow the capital key used in the APP.[94][72][99]

The flexibility to deviate from the capital key is key for the PEPP: because of the uncertainty caused by COVID-19[72] it was needed to prevent tightening financial conditions.[98] They prevent yield spreads between the bonds of different member states, caused by the flight-to-safety of investors.[94][100][101] The flexibility in asset purchases allows for fluctuations in the distribution of purchases across asset classes and among jurisdictions to prevent market fragmentation.[77][78][92][102][103] Following this strategy, the PEPP distributed the money among countries in need.[104][105][106] The APP follows the capital key strategy, from which no deviations are possible. This makes the APP not able to counter the crisis effectively.[72] Margrethe Vestager, European Commissioner for Competition argued "We will need to distribute in order to recover together. These increasing asymmetries will otherwise fragment the single market to a level otherwise none of us is willing to accept,.",[107] as economists feared that the strong economies would come out of the crisis stronger while weak economies would deteriorate because of the crisis.[75] The PEPP is thus a tool used by the ECB to purchase both private and public securities according to the specific needs of EU-countries caused by the COVID-19-crisis.[105] The temporal flexibility from the capital key meant that the ECB could especially prevent the rise of Italian and Spanish yield spreads.[75]

Assets eligible under the PEPP

Assets meeting the eligibility criteria of the APP were also eligible under the PEPP.[98] However, the PEPP complemented the APP eligibility framework given the specificity of the PEPP-context of crisis requiring a more tailored response.[105] Among the distinctions is that for the first time since the Greek government-debt crisis, Greek debt is given a waiver under the PEPP so that it could be purchased by the ECB under this programme.[105][106][108] This waiver was given based on several considerations from the ECB: there was a need to alleviate the pressures stemming from the pandemic on the Greek financial markets; Greece was already and would be closely monitored by giving the waiver; and Greece regained market access.[91] This proved to be controversial,[72] as Greece is the eurozone's riskiest issuer.[109] Non-financial commercial paper with a remaining maturity of at least 28 days was also eligible for purchase under the PEPP. The maturity criteria for public sector ranges form 70 days up to 30 years and 364 days.[98][110] As the PEPP can deviate from the capital key strategy, there is also no hard limit on the 33% of a single security per issuer or 33% of a member state's total outstanding security.[94]

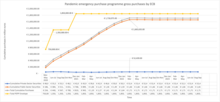

Timeline of the PEPP and TLTRO announcements and purchases

On 12 March 2020, Christine Lagarde announced in a press conference a set of policy measures to support the European economy in the rising wake of the pandemic, saying that "all the flexibilities that are embedded in the framework of the asset purchase programme " but at the same time she stated that the ECB " is not here to close spreads."[78][111][112] This left markets disappointed and let to a particular widening yield spreads in Spain, Italy and Greece.[113] However, the Governing Council announced firstly to provide immediate liquidity through conducting additional LTROs; secondly, to provide more favorable terms on the TLTRO III operations outstanding in the period between June 2020 and June 2021; and thirdly, to announce an additional package of net asset purchases of €120 billion by the end of 2020 under the already existing APP.[99][111][114]

A day later, on 13 March 2020, the WHO declared Europe the centre of the pandemic.[115][116]

By March 17, a week after the press conference given by Ms. Lagarde, stock index plateaued while the interest rate spread kept on rising over 2.8%.[114]

On 18 of March 2020, 6 days after the previous press conference, the ECB announced the launch of the PEPP worth €750 billion[113][114][105][99] to boost liquidity in the European economy[74] and to contain any sharp increases in sovereign yield spreads.[117][118] This announcement led to an immediate reboot in stock prices[114] and came one day after the spike of sovereign risk spreads.[118] The PEPP became effective as from 24 March 2020, six days after the announcement of the PEPP.[114] By announcing the PEPP the ECB deviated from its pattern of prodding fiscal authorities into action before announcing any monetary stimulus.[75] Together with the additional €120 billion announced on March 12, the PEPP amounted up to 7.3% of the euro-area GDP.[102]

On 30 April 2020, the ECB Governing council introduced the Pandemic Emergency Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (PELTROs), with an interest rate of 25bp below the average rate applied in LTROs and for the first time negative.[119][78]

On 4 June 2020, the ECB announced[120] it would expand the PEPP by another €600 billion,[121] as it became clear that the pandemic would continue to harm European economies increasing the total emergency package up to €1.350 trillion.[72][96][99][113] Following Carsten Brzeski, chief economist at ING, dents this ECB decision " any further speculation about whether or not the ECB is willing to play its role of lender of last resort for the eurozone."[122] The expansion showed that the ECB is committed to achieve the price stability objective.[123] However the ECB reiterated that additional fiscal measures should be taken, as the PEPP cannot deliver economic recovery on its own.[106]

Half a year later, on 10 December 2020, the ECB announced its final expansion of the PEPP worth another €500 billion, totalling the final PEPP to €1.850 trillion,[124][92][74] corresponding to 15.4% of the euro-area GDP of 2019.[118] At the same press conference, the ECB announced that it expected to extend the horizon for net purchases of the PEPP until at least the end of March 2022.[124]

In December 2021 the ECB announced that it would discontinue net purchases under the PEPP as from the end of March 2022 and that it intended to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities at least until the end of 2024.[104][126]

On 31 March 2022, at the end of the net purchases, the net purchases amounted to €1.718 billion euros, of which €1.665 billion is invested in public sector securities and €52 billion in private sector securities.[71] Of the total €1.850 billion available under the PEPP, 93% of the full envelope wase used, due to indications of decreased financial stress in the Euro Area, mainly thanks to relaxation of COVID restrictions and the reopening of European markets.[127]