A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Food security is the state of having reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food. The availability of food for people of any class, gender or religion is another element of food security. Similarly, household food security is considered to exist when all the members of a family, at all times, have access to enough food for an active, healthy life.[1] Individuals who are food-secure do not live in hunger or fear of starvation.[2] Food security includes resilience to future disruptions of food supply. Such a disruption could occur due to various risk factors such as droughts and floods, shipping disruptions, fuel shortages, economic instability, and wars.[3] Food insecurity is the opposite of food security: a state where there is only limited or uncertain availability of suitable food.

The concept of food security has evolved over time. The four pillars of food security include availability, access, utilization, and stability.[4] In addition, there are two more dimensions that are important: agency and sustainability. These six dimensions of food security are reinforced in conceptual and legal understandings of the right to food.[5][6] The World Food Summit in 1996 declared that "food should not be used as an instrument for political and economic pressure."[7][8]

There are many causes of food insecurity. The most important ones are high food prices and disruptions in global food supplies for example due to war. There is also climate change, water scarcity, land degradation, agricultural diseases, pandemics and disease outbreaks that can all lead to food insecurity.

The effects of food insecurity can include hunger and even famines. Chronic food insecurity translates into a high degree of vulnerability to hunger and famine.[9] Chronic hunger and malnutrition in childhood can lead to stunted growth of children.[10] Once stunting has occurred, improved nutritional intake after the age of about two years is unable to reverse the damage. Severe malnutrition in early childhood often leads to defects in cognitive development.[11]

Definition

Food security, as defined by the World Food Summit in 1996, is "when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life".[12][13]

Food insecurity, on the other hand, as defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), is a situation of "limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways."[14]

At the 1974 World Food Conference, the term food security was defined with an emphasis on supply; it was defined as the "availability at all times of adequate, nourishing, diverse, balanced and moderate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset the fluctuations in production and prices."[15] Later definitions added demand and access issues to the definition. The first World Food Summit, held in 1996, stated that food security "exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life."[16][7]

Chronic (or permanent) food insecurity is defined as the long-term, persistent lack of adequate food.[17] In this case, households are constantly at risk of being unable to acquire food to meet the needs of all members. Chronic and transitory food insecurity are linked since the reoccurrence of transitory food security can make households more vulnerable to chronic food insecurity.[18]

As of 2015[update], the concept of food security has mostly focused on food calories rather than the quality and nutrition of food. The concept of nutrition security or nutritional security evolved as a broader concept. In 1995, it was defined as "adequate nutritional status in terms of protein, energy, vitamins, and minerals for all household members at all times."[19]: 16 It is also related to the concepts of nutrition education and nutritional deficiency.[citation needed]

Measurement

Food security can be measured by the number of calories to digest per person per day, available on a household budget.[20][21] In general, the objective of food security indicators and measurements is to capture some or all of the main components of food security in terms of food availability, accessibility, and utilization/adequacy. While availability (production and supply) and utilization/adequacy (nutritional status/ anthropometric measurement) are easier to estimate and therefore more popular, accessibility (the ability to acquire a sufficient quantity and quality of food) remains largely elusive.[22] The factors influencing household food accessibility are often context-specific.[23]

FAO has developed the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) as a universally applicable experience-based food security measurement scale derived from the scale used in the United States. Thanks to the establishment of a global reference scale and the procedure needed to calibrate measures obtained in different countries, it is possible to use the FIES to produce cross-country comparable estimates of the prevalence of food insecurity in the population.[24] Since 2015, the FIES has been adopted as the basis to compile one of the indicators included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) monitoring framework.[25]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) collaborate every year to produce The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, or SOFI report (known as The State of Food Insecurity in the World until 2015).

The SOFI report measures chronic hunger (or undernourishment) using two main indicators, the Number of undernourished (NoU) and the Prevalence of undernourishment (PoU). Beginning in the early 2010s, FAO incorporated more complex metrics into its calculations, including estimates of food losses in retail distribution for each country and the volatility in agri-food systems. Since 2016, it has also reported the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity based on the FIES.[citation needed]

Several measurements have been developed to capture the access component of food security, with some notable examples developed by the USAID-funded Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) project.[23][26][27][28] These include:

- Household Food Insecurity Access Scale – measures the degree of food insecurity (inaccessibility) in the household in the previous month on a discrete ordinal scale.

- Household Dietary Diversity Scale – measures the number of different food groups consumed over a specific reference period (24hrs/48hrs/7days).

- Household Hunger Scale – measures the experience of household food deprivation based on a set of predictable reactions, captured through a survey and summarized in a scale.

- Coping Strategies Index (CSI) – assesses household behaviors and rates them based on a set of varied established behaviors on how households cope with food shortages. The methodology for this research is based on collecting data on a single question: "What do you do when you do not have enough food, and do not have enough money to buy food?"[29][30][31]

Prevalence of food insecurity

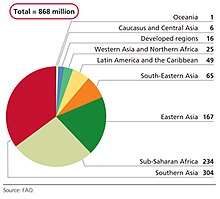

Close to 12 percent of the global population was severely food insecure in 2020, representing 928 million people -148 million more than in 2019.[5] A variety of reasons lie behind the increase in hunger over the past few years. Slowdowns and downturns since the 2008-9 financial crisis have conspired to degrade social conditions, making undernourishment more prevalent. Structural imbalances and a lack of inclusive policies have combined with extreme weather events, altered environmental conditions, and the spread of pests and diseases, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, triggering stubborn cycles of poverty and hunger. In 2019, the high cost of healthy diets together with persistently high levels of income inequality put healthy diets out of reach for around 3 billion people, especially the poor, in every region of the world.[5]

Inequality in the distributions of assets, resources and income, compounded by the absence or scarcity of welfare provisions in the poorest of countries, is further undermining access to food. Nearly a tenth of the world population still lives on US$1.90 or less a day, with sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia the regions most affected.[33]

High import and export dependence ratios are meanwhile making many countries more vulnerable to external shocks. In many low-income economies, debt has swollen to levels far exceeding GDP, eroding growth prospects.

Finally, there are increasing risks to institutional stability, persistent violence, and large-scale population relocation as a consequence of the conflicts. With the majority of them being hosted in developing nations, the number of displaced individuals between 2010 and 2018 increased by 70% between 2010 and 2018 to reach 70.8 million.[34]

Recent editions of the SOFI report (The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World) present evidence that the decades-long decline in hunger in the world, as measured by the number of undernourished (NoU), has ended. In the 2020 report, FAO used newly accessible data from China to revise the global NoU downwards to nearly 690 million, or 8.9 percent of the world population – but having recalculated the historic hunger series accordingly, it confirmed that the number of hungry people in the world, albeit lower than previously thought, had been slowly increasing since 2014. On broader measures, the SOFI report found that far more people suffered some form of food insecurity, with 3 billion or more unable to afford even the cheapest healthy diet.[35] Nearly 2.37 billion people did not have access to adequate food in 2020 – an increase of 320 million people compared to 2019.[36][37]

FAO's 2021 edition of The State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) further estimates that an additional 1 billion people (mostly in lower- and upper-middle-income countries) are at risk of not affording a healthy diet if a shock were to reduce their income by a third.[38]

The 2021 edition of the SOFI report estimated the hunger excess linked to the COVID-19 pandemic at 30 million people by the end of the decade[5] – FAO had earlier warned that even without the pandemic, the world was off track to achieve Zero Hunger or Goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals – it further found that already in the first year of the pandemic, the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) had increased 1.5 percentage points, reaching a level of around 9.9 percent. This is the mid-point of an estimate of 720 to 811 million people facing hunger in 2020 – as many as 161 million more than in 2019.[36][37] The number had jumped by some 446 million in Africa, 57 million in Asia, and about 14 million in Latin America and the Caribbean.[5]

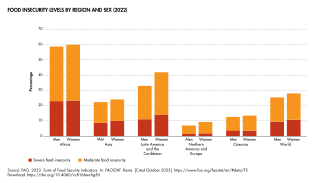

At the global level, the prevalence of food insecurity at a moderate or severe level, and severe level only, is higher among women than men, magnified in rural areas.[39]

In 2023, the Global Report on Food Crises revealed that acute hunger affected approximately 282 million people across 59 countries, an increase of 24 million from the previous year. This rise in food insecurity was primarily driven by conflicts, economic shocks, and extreme weather. Regions like the Gaza Strip and South Sudan were among the hardest hit, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions to address and mitigate global hunger effectively.[40]

Vulnerable groups most affected

Children

Food insecurity in children can lead to developmental impairments and long term consequences such as weakened physical, intellectual and emotional development.[41]

By way of comparison, in one of the largest food producing countries in the world, the United States, approximately one out of six people are "food insecure," including 17 million children, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2009.[42] A 2012 study in the Journal of Applied Research on Children found that rates of food security varied significantly by race, class and education. In both kindergarten and third grade, 8% of the children were classified as food insecure, but only 5% of white children were food insecure, while 12% and 15% of black and Hispanic children were food insecure, respectively. In third grade, 13% of black and 11% of Hispanic children were food insecure compared to 5% of white children.[43][44]

Women

Gender inequality both leads to and is a result of food insecurity. According to estimates, girls and women make up 60% of the world's chronically hungry and little progress has been made in ensuring the equal right to food for women enshrined in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.[45][46]

At the global level, the gender gap in the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity grew even larger in the year of COVID-19 pandemic. The 2021 SOFI report finds that in 2019 an estimated 29.9 percent of women aged between 15 and 49 years around the world were affected by anemia – now a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicator (2.2.3).[5]

The gap in food insecurity between men and women widened from 1.7 percentage points in 2019 to 4.3 percentage points in 2021.[47]

Women play key roles in maintaining all four pillars of food security: as food producers and agricultural entrepreneurs; as decision-makers for the food and nutritional security of their households and communities and as "managers" of the stability of food supplies in times of economic hardship.[39]

The gender gap in accessing food increased from 2018 to 2019, particularly at moderate or severe levels.[39]

History

Famines have been frequent in world history. Some have killed millions and substantially diminished the population of a large area. The most common causes have been drought and war, but the greatest famines in history were caused by economic policy.[49] One economic policy example of famine was the Holodomor (Great Famine) induced by the Soviet Union's communist economic policy resulting in 7–10 million deaths.[50]

In the late 20th century the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen observed that "there is no such thing as an apolitical food problem."[51] While drought and other naturally occurring events may trigger famine conditions, it is government action or inaction that determines its severity, and often even whether or not a famine will occur. The 20th century has examples of governments, such as Collectivization in the Soviet Union or the Great Leap Forward in the People's Republic of China undermining the food security of their nations. Mass starvation is frequently a weapon of war, as in the blockade of Germany in World War I and World War II, the Battle of the Atlantic, and the blockade of Japan during World War I and World War II and in the Hunger Plan enacted by Nazi Germany.[citation needed]

Pillars of food security

The WHO states that three pillars that determine food security: food availability, food access, and food use and misuse.[52] The FAO added a fourth pillar: the stability of the first three dimensions of food security over time.[2] In 2009, the World Summit on Food Security stated that the "four pillars of food security are availability, access, utilization, and stability."[4] Two additional pillars of food security were recommended in 2020 by the High-Level Panel of Experts for the Committee on World Food Security: agency and sustainability.[6]

Availability

Food availability relates to the supply of food through production, distribution, and exchange.[53] Food production is determined by a variety of factors including land ownership and use; soil management; crop selection, breeding, and management; livestock breeding and management; and harvesting.[18] Crop production can be affected by changes in rainfall and temperatures.[53] The use of land, water, and energy to grow food often compete with other uses, which can affect food production.[54] Land used for agriculture can be used for urbanization or lost to desertification, salinization or soil erosion due to unsustainable agricultural practices.[54] Crop production is not required for a country to achieve food security. Nations do not have to have the natural resources required to produce crops to achieve food security, as seen in the examples of Japan[55][56] and Singapore.[57]

Because food consumers outnumber producers in every country,[57] food must be distributed to different regions or nations. Food distribution involves the storage, processing, transport, packaging, and marketing of food.[18] Food-chain infrastructure and storage technologies on farms can also affect the amount of food wasted in the distribution process.[54] Poor transport infrastructure can increase the price of supplying water and fertilizer as well as the price of moving food to national and global markets.[54] Around the world, few individuals or households are continuously self-reliant on food. This creates the need for a bartering, exchange, or cash economy to acquire food.[53] The exchange of food requires efficient trading systems and market institutions, which can affect food security.[17] Per capita world food supplies are more than adequate to provide food security to all, and thus food accessibility is a greater barrier to achieving food security.[57]

Access

Food access refers to the affordability and allocation of food, as well as the preferences of individuals and households.[53] The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights noted that the causes of hunger and malnutrition are often not a scarcity of food but an inability to access available food, usually due to poverty.[58] Poverty can limit access to food, and can also increase how vulnerable an individual or household is to food price spikes.[17] Access depends on whether the household has enough income to purchase food at prevailing prices or has sufficient land and other resources to grow its food.[59] Households with enough resources can overcome unstable harvests and local food shortages and maintain their access to food.[57]

There are two distinct types of access to food: direct access, in which a household produces food using human and material resources, and economic access, in which a household purchases food produced elsewhere.[18] Location can affect access to food and which type of access a family will rely on.[59] The assets of a household, including income, land, products of labor, inheritances, and gifts can determine a household's access to food.[18] However, the ability to access sufficient food may not lead to the purchase of food over other materials and services.[17] Demographics and education levels of members of the household as well as the gender of the household head determine the preferences of the household, which influences the type of food that is purchased.[59] A household's access to adequate nutritious food may not assure adequate food intake for all household members, as intrahousehold food allocation may not sufficiently meet the requirements of each member of the household.[17] The USDA adds that access to food must be available in socially acceptable ways, without, for example, resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing, or other coping strategies.[1]

The monetary value of global food exports multiplied by 4.4 in nominal terms between 2000 and 2021, from US$380 billion in 2000 to US$1.66 trillion in 2021.[60]

Utilization

The next pillar of food security is food utilization, which refers to the metabolism of food by individuals.[57] Once the food is obtained by a household, a variety of factors affect the quantity and quality of food that reaches members of the household. To achieve food security, the food ingested must be safe and must be enough to meet the physiological requirements of each individual.[17] Food safety affects food utilization,[53] and can be affected by the preparation, processing, and cooking of food in the community and household.[18]

Nutritional values[53] of the household determine food choice,[18] and whether food meets cultural preferences is important to utilization in terms of psychological and social well-being.[61] Access to healthcare is another determinant of food utilization since the health of individuals controls how the food is metabolized.[18] For example, intestinal parasites can take nutrients from the body and decrease food utilization.[57] Sanitation can also decrease the occurrence and spread of diseases that can affect food utilization.[18][62] Education about nutrition and food preparation can affect food utilization and improve this pillar of food security.[57]

Stability

Food stability refers to the ability to obtain food over time. Food insecurity can be transitory, seasonal, or chronic.[18] In transitory food insecurity, food may be unavailable during certain periods of time.[17] At the food production level, natural disasters[17] and drought[18] result in crop failure and decreased food availability. Civil conflicts can also decrease access to food.[17] Instability in markets resulting in food-price spikes can cause transitory food insecurity. Other factors that can temporarily cause food insecurity are loss of employment or productivity, which can be caused by illness. Seasonal food insecurity can result from the regular pattern of growing seasons in food production.[18]

Agency

Agency refers to the capacity of individuals or groups to make their own decisions about what foods they eat, what foods they produce, how that food is produced, processed, and distributed within food systems, and their ability to engage in processes that shape food system policies and governance.[6] This term shares similar values to those of another important concept, Food sovereignty.[63]

Sustainability

Sustainability refers to the long-term ability of food systems to provide food security and nutrition in a way that does not compromise the economic, social, and environmental bases that generate food security and nutrition for future generations.[6]

Causes of food insecurity

High food prices

During 2022 and 2023 there were food crises in several regions as indicated by rising food prices. In 2022, the world experienced significant food price inflation along with major food shortages in several regions. Sub-Saharan Africa, Iran, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Iraq were most affected.[64][65][66] Prices of wheat, maize, oil seeds, bread, pasta, flour, cooking oil, sugar, egg, chickpea and meat increased.[67][68][69] Many factors have contributed to the ongoing world food crisis. These include supply chain disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021–2023 global energy crisis, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and floods and heatwaves during 2021 (which destroyed key American and European crops).[70] Droughts were also a factor; in early 2022, some areas of Spain and Portugal lost 60-80% of their crops due to widespread drought.[71]

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, food prices were already at a record high. 82 million East Africans and 42 million West Africans faced acute food insecurity in 2021.[72] By the end of 2022, more than 8 million Somalis were in need of food assistance.[73] In February 2022, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported a 20% rise in food prices since February 2021.[74] The war further pushed this increase to 40% in March 2022 but was reduced to 18% by January 2023.[68] But the FAO warns that inflation of food prices will continue in many countries.[75]Pandemics and disease outbreaks

The World Food Programme has stated that pandemics such as the COVID-19 pandemic risk undermining the efforts of humanitarian and food security organizations to maintain food security.[76] The International Food Policy Research Institute expressed concerns that the increased connections between markets and the complexity of food and economic systems could cause disruptions to food systems during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically affecting the poor.[77]

The Ebola outbreak in 2014 led to increases in the prices of staple foods in West Africa.[78] Stringent lockdowns, travel restrictions, and disruptions to labor forces resulted in bottlenecks affecting the production and distribution of goods. Notably, the food supply chain experienced significant disruptions as the pandemic strained logistics, labor availability, and demand patterns. While progress in combating COVID-19 has provided some relief, the pandemic's lasting effects persist, including shifts in consumer behavior and the ongoing necessity for health and safety measures.[79]

Fossil fuel dependence

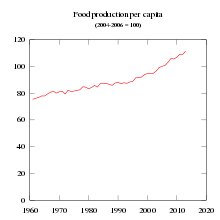

Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by 250%. The energy for the Green Revolution was provided by fossil fuels in the form of fertilizers (natural gas), pesticides (oil), and hydrocarbon-fueled irrigation.[81]

Natural gas is a major feedstock for the production of ammonia, via the Haber process, for use in fertilizer production.[82][83] The development of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer has significantly supported global population growth — it has been estimated that almost half the people on Earth are currently fed as a result of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer use.[84][85]

Agricultural diseases

Diseases affecting livestock or crops can have devastating effects on food availability especially if there are no contingency plans in place. For example, Ug99, a lineage of wheat stem rust, which can cause up to 100% crop losses, is present in wheat fields in several countries in Africa and the Middle East and is predicted to spread rapidly through these regions and possibly further afield, potentially causing a wheat production disaster that would affect food security worldwide.[86][87]

Disruption in global food supplies due to war

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has disrupted global food supplies.[88] The conflict has severely impacted food supply chains with noteworthy effects on production, sourcing, manufacturing, processing, logistics, and significant shifts in demand among nations reliant on imports from Ukraine.[88] The European Union's imposition of sanctions on Russia has added complexity to trade relations.[79] In Asia and the Pacific, many of those regions' countries depend on the importation of basic food staples such as wheat and also fertilizer, with nearly 1.1 billion lacking a healthy diet caused by poverty and ever-increasing food prices.[89]

Environmental degradation and overuse

Land degradation

Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and a decline of agricultural yields.[90] Other causes of land degradation include for example deforestation, overgrazing, and over-exploitation of vegetation for use.[91] Approximately 40 percent of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[92]

While the Green Revolution was critical in supporting a larger population through the mid-1900s to now by increasing crop yields, it has also resulted in environmental degradation particularly through land use, soil degradation, and deforestation. Over-farming of agricultural land due to the Green Revolution has caused contamination and erosion of soil, and a reduction in biodiversity due to pesticide usage (as well as deforestation). Malnutrition rates and food insecurity could increase again as land and water resources are depleted.[93]

Water scarcity

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk