A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| Currency | Bangladeshi taka (BDT, ৳) |

|---|---|

| 1 July – 30 June | |

Trade organizations | SAFTA, SAARC, BIMSTEC, WTO, AIIB, IMF, Commonwealth of Nations, World Bank, ADB, Developing-8 |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | 169,800,000 (2022)[5] |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector | (FY2020)[11] |

Population below poverty line |

|

Labor force | |

Labor force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

Main industries | |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | Cotton textiles and knitwear,[25][26] jute and jute goods,[25][26] fish and seafood,[26] leather and leather goods, home textiles, pharmaceuticals, processed food,[27] plastics, bicycles[26] |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports |

|

Import goods | Liquified natural gas, crude oil and petroleum, machinery and equipment, chemicals, cotton, foodstuffs |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt |

|

| Public finances | |

| −3.2% of GDP (2017 est.)[33] | |

| Revenues | |

| Expenses | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Bangladesh is a major developing mixed economy.[3] As the second-largest economy in South Asia,[44][45] Bangladesh's economy is the 35th largest in the world in nominal terms, and 25th largest by purchasing power parity. Bangladesh is seen by various financial institutions as one of the Next Eleven. It has been transitioning from being a frontier market into an emerging market. Bangladesh is a member of the South Asian Free Trade Area and the World Trade Organization. In fiscal year 2021–2022, Bangladesh registered a GDP growth rate of 7.2% after the global pandemic.[46] Bangladesh is one of the fastest growing economies in the world.

Industrialisation in Bangladesh received a strong impetus after the partition of India due to labour reforms and new industries.[47] Between 1947 and 1971, East Bengal generated between 70% and 50% of Pakistan's exports.[48][49] Modern Bangladesh embarked on economic reforms in the late 1970s which promoted free markets and foreign direct investment. By the 1990s, the country had a booming ready-made garments industry. As of 16 March 2024, Bangladesh has the highest number of green garment factories in the world with Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification from the United States Green Building Council (USGBC), where 80 are platinum-rated, 119 are gold-rated, 10 are silver, and four are without any rating.[50] As of 6 March 2024, Bangladesh is home to 54 of the top 100 LEED Green Garment Factories globally, including 9 out of the top 10, and 18 out of the top 20.[51] As of 27 April 2024, Bangladesh has a growing pharmaceutical industry with 12 percent average annual growth rate. Bangladesh is the only nation among the 48 least-developed countries that is almost self-sufficient when it comes to medicine production as local companies meet 98 percent of the domestic demand for pharmaceuticals.[52] Remittances from the large Bangladeshi diaspora became a vital source of foreign exchange reserves.[53] Agriculture in Bangladesh is supported by government subsidies and ensures self-sufficiency in food production.[54][55] Bangladesh has pursued export-oriented industrialisation.[56][57]

Bangladesh experienced robust growth after the pandemic with macroeconomic stability, improvements in infrastructure, a growing digital economy, and growing trade flows.[58] Tax collection remains very low, with tax revenues accounting for only 7.7% of GDP.[59] Bangladesh's banking sector has a large amount of non-performing loans or loan defaults, which have caused a lot of concern.[59][60] The private sector makes up 80% of GDP.[61][62] The Dhaka Stock Exchange and Chittagong Stock Exchange are the two stock markets of the country.[63] Most Bangladeshi businesses are privately owned small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) which make up 90% of all businesses.[64]

Economic history

Precolonial period

Punch-marked coins are the earliest form of currency found in Bangladesh, dating back to the Iron Age and the first millennium BCE.[65][66] 1st century Roman coins with images of Hercules have been excavated in Bangladesh and point to trade links with the Roman world.[67] The Wari-Bateshwar ruins are believed to be the emporium (trading center) of Sounagoura mentioned by Roman geographer Claudius Ptolemy.[68] The eastern segment of Bengal was a historically prosperous region.[69] The Ganges Delta provided advantages of a mild, almost tropical climate, fertile soil, ample water, and an abundance of fish, wildlife, and fruit.[69] Living standards for the elite were comparatively better than other parts of the Indian subcontinent.[69] Trade routes like the Grand Trunk Road, Tea Horse Road and Silk Road connected the region to the wider neighborhood.[69] Between 400 and 1200, the region had a well-developed economy in terms of land ownership, agriculture, livestock, shipping, trade, commerce, taxation, and banking.[70] Muslim trade with Bengal increased after the fall of the Sasanian Empire and the Arab takeover of Persian trade routes. Much of this trade occurred east of the Meghna River in southeastern Bengal.[71] After 1204, Muslim conquerors inherited the gold and silver reserves of pre-Islamic kingdoms.

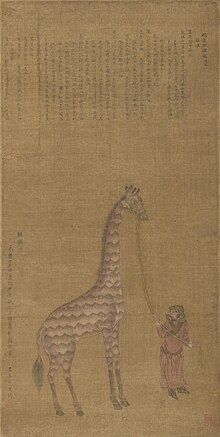

The Bengal Sultanate presided over a mercantile empire of its own. Bengali ships were the largest ships in the Bay of Bengal and other parts of the Indian Ocean trade network. Ship-owning merchants often acted as royal envoys of the Sultan.[72] A large number of wealthy Bengali merchants and shipowners lived in Malacca.[73] A vessel from Bengal transported embassies from Brunei and Sumatra to China.[74] Bengal and the Maldives operated the largest shell currency network in history.[75] A Masai giraffe from Malindi in Africa was shipped to Bengal and later gifted to the Emperor of China as a gift from the Sultan of Bengal.[76] The rulers of Arakan looked to Bengal for economic, political and cultural capital.[77] The Sultan of Bengal financed projects in the Hejaz region of Arabia.[78]

Under Mughal rule, Bengal operated as a centre of the worldwide muslin, silk and pearl trades.[69] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example.[79] Bengal shipped saltpeter to Europe, sold opium in Indonesia, exported raw silk to Japan and the Netherlands, and produced cotton and silk textiles for export to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[80] Real wages and living standards in 18th-century Bengal were comparable to Britain, which in turn had the highest living standards in Europe.[81]

During the Mughal era, the most important centre of cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[82] Bengali agriculturalists rapidly learned techniques of mulberry cultivation and sericulture, establishing Bengal as a major silk-producing region of the world.[83] Bengal accounted for more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks imported by the Dutch from Asia, for example.[79]

Bengal also had a large shipbuilding industry. The shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[84] The region was also a center of ship-repairing.[84] Bengali shipbuilding was advanced compared to European shipbuilding at the time. An important innovation in shipbuilding was the introduction of a flushed deck design in Bengal rice ships, resulting in hulls that were stronger and less prone to leak than the structurally weak hulls of traditional European ships built with a stepped deck design. The English East India Company later duplicated the flushed-deck and hull designs of Bengal rice ships in the 1760s, leading to significant improvements in seaworthiness and navigation for European ships during the Industrial Revolution.[85] Among the oldest businesses from the pre-colonial and Mughal periods, the biryani restaurant Fakhruddin's traces its history to the era of the Nawabs of Bengal.[86]

Colonial period

The British East India Company, that took complete control of Bengal in 1793 by abolishing Nizamat (local rule), chose to develop Calcutta, now the capital city of West Bengal, as their commercial and administrative center for the Company-held territories in South Asia.[69] The development of East Bengal was thereafter limited to agriculture.[69] The administrative infrastructure of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries focused on East Bengal's function as a primarily agricultural producer—chiefly of rice, tea, teak, cotton, sugar cane and jute — for processors and traders in the British Empire.[69] British rule saw the introduction of railways.[87] The Hardinge Bridge was built to carry trains across the Padma River. In the early 20th century, Eastern Bengal and Assam was established in the British Raj to promote jobs, education and investment in East Bengal. In 1928, the Port of Chittagong was declared to be a "Major Port" of British India.[87] East Bengal extended its rice economy into Arakan Division in British Burma.[88] The river and sea ports of East Bengal, including Goalundo Ghat,[89] the Port of Dhaka, the Port of Narayanganj, and the Port of Chittagong became entrepots for trade between Bengal, Assam and Burma. Some of Bangladesh's venerable and oldest companies were born in British Bengal, including A K Khan & Company, M. M. Ispahani Limited, James Finlay Bangladesh, and Anwar Group of Industries.

Pakistan period

The partition of India changed the economic geography of the region. The Pakistani government in East Bengal prioritized industries based on local raw materials like jute, cotton, and leather. The Korean War drove up demand for jute products.[90] Adamjee Jute Mills, the world's largest jute processing plant, was built in the Port of Narayanganj. The plant was a symbol of East Pakistan's industrialization. Living standards began to gradually improve. Labor reforms in 1958 eventually benefitted a future independent Bangladesh to develop industry.[47] Free market principles were generally accepted. The government promoted an industrial policy which aimed to produce consumer goods as quickly as possible in order to avoid dependence on imports. Certain sectors, like public utilities, fell under state ownership.[91] Natural gas in Sylhet was discovered by the Burmah Oil Company in 1955.[92] By the late 1960s, East Pakistan's share of Pakistan's exports went down from 70% to 50%.[48] Pakistan's rulers launched a so-called "Decade of Development" that "resulted in numerous economic and social contradictions, which played themselves out, not just in the 1960s, but beyond, where Ayub Khan’s rule created the social and economic conditions leading to the separation of East Pakistan".[93] According to the World Bank, economic discrimination against East Pakistan included diverting foreign aid and other funds to West Pakistan, the use of East Pakistan's foreign-exchange surpluses to finance West Pakistani imports, and refusal by the central government to release funds allocated to East Pakistan.[94] Rehman Sobhan paraphrased the Two-Nation Theory into the Two Economies Theory by arguing that East and West Pakistan diverged and became two different economies within one country.[95][96][97][98]

Post-independence period

Socialist era (1972–1975)

After its independence from Pakistan, Bangladesh initially followed a socialist economy for five years, which proved to be a blunder by the Awami League government. The state nationalized all banks, insurance companies, and 580 industrial plants.[99] Private companies had to operate under heavy regulation and restrictions. For example, profit limits were imposed on companies. Any company with revenues or profits above the limit were susceptible to nationalization. Many of the nationalized industries were abandoned by West Pakistanis during the war;[99] while many pro-Awami League and other Bengali businesses also suffered nationalization of properties and industries. Land ownership was restricted to less than 25 bighas. Land owners with more than 25 bighas were subjected to taxes.[99] Farmers had to sell their products at prices set by the government instead of the market. There was hardly any foreign investment. Since Bangladesh followed a socialist economy, it underwent a slow growth of producing experienced entrepreneurs, managers, administrators, engineers, and technicians.[100] There were critical shortages of essential food grains and other staples because of wartime disruptions.[100] External markets for jute had been lost because of the instability of supply and the increasing popularity of synthetic substitutes.[100] Foreign exchange resources were minuscule, and the banking and monetary systems were unreliable.[100] Although Bangladesh had a large work force, the vast reserves of under trained and underpaid workers were largely illiterate, unskilled, and underemployed.[100] Commercially exploitable industrial resources, except for natural gas, were lacking.[100] Inflation, especially for essential consumer goods, ran between 300 and 400 percent.[100] The war of independence had crippled the transportation system.[100] Hundreds of road and railroad bridges had been destroyed or damaged, and rolling stock was inadequate and in poor repair.[100] The new country was still recovering from a severe cyclone that hit the area in 1970 and caused 250,000 deaths.[100] India came forward immediately with critically measured economic assistance in the first months after Bangladesh achieved independence from Pakistan.[100] Between December 1971 and January 1972, India committed US$232 million in aid to Bangladesh from the politico-economic aid India received from the US and USSR.[100] The Awami League initiated work for the Ghorashal Fertilizer Factory and the Ashuganj Power Station. In spite of restrictions, several of Bangladesh's leading companies in the future were founded during this period, including BEXIMCO and Advanced Chemical Industries.

Military rule and economic reforms (1975–1990)

After 1975 coups, new Bangladeshi military leaders began to promote private industry and turned their attention to developing new industrial capacity and rehabilitating the economy.[101] The socialist economic model adopted by early leaders had resulted in inefficiency and economic stagnation.[101] Beginning in late 1975, the government gradually gave greater scope to private sector participation in the economy, a pattern that has continued.[101] The Dhaka Stock Exchange was re-opened in 1976. The government established special economic zones called Export Processing Zones (EPZs) to attract investors and promote export industries. These zones have played a key role in Bangladesh's export economy. The government also de-nationalized and privatized state-owned industries by either returning them to their original owners or selling them to private buyers.[101] Inefficiency in the public sector gradually increased; and left-wing opposition grew against the export of natural gas.[101]

The 1980s saw the emergence of dynamic local brands like PRAN. Muhammad Yunus began experimenting with microcredit in the late 1970s. In 1983, the Grameen Bank was established. Bangladesh became the pioneer of the modern microcredit industry, with leading players like Grameen Bank, BRAC and Proshika.[102] In the industrial sector, two policy innovations in the mid-1980s helped exporters. The reforms introduced the back-to-back letter of credit and duty-drawback facilities through bonded warehouses. These reforms removed major constraints for the country's fledgling garment industry. The reforms allowed a garment manufacturer to obtain letters of credit from domestic banks to finance its import of inputs, by showing letters of credit from foreign buyers of garments. The reforms also reimbursed manufacturers the duty paid on imported inputs on proof that the inputs, stored in bonded warehouses, had been used to manufacture the exports. These reforms spurred the growth of industry into the world's second largest textile exporting sector.[103] In the mid-1980s, there were encouraging signs of progress.[101] Economic policies aimed at encouraging private enterprise and investment, privatising public industries, reinstating budgetary discipline, and liberalising the import regime were accelerated.[101] The International Finance Investment and Commerce Bank was set up as a multinational bank for Bangladesh, Nepal and the Maldives.

Economic growth (1991–present)

From 1991 to 1993, the government engaged in an enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). A series of economic liberalization measures was introduced by finance minister Saifur Rahman, including opening up sectors like telecom to foreign investment.[104] The Chittagong Stock Exchange was also set up. The 1990s was a boon for the private sector. Banking, telecommunications, aviation and tertiary education saw new private players and increased competition. The pharmaceutical industry in Bangladesh grew to meet 98% of domestic demand.[105] The ceramics industry in Bangladesh developed to meet local demand for 96% of tableware ceramics, 77% of tiles and 89% of sanitary ceramics.[106] The Chittagong-based steel industry in Bangladesh exploited scrap steel from ship-breaking yards and started contributing to shipbuilding in Bangladesh.

But the government failed to sustain reforms in large part because of preoccupation with the government's domestic political troubles, including tensions between the Awami League, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jatiya Party.[101] Frequent hartals and strikes disrupted the economy. In the late 1990s the government's economic policies became more entrenched, and some gains were lost, which was highlighted by a precipitous drop in foreign direct investment in 2000 and 2001.[101] Many new private commercial banks were given licenses to operate. Between 2001 and 2006, annual GDP growth touched an average of 5-6%. In June 2003 the IMF approved 3-year, $490-million plan as part of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) for Bangladesh that aimed to support the government's economic reform programme up to 2006.[101] Seventy million dollars was made available immediately.[101] In the same vein the World Bank approved $536 million in interest-free loans.[101] The economy saw continuous real GDP growth of at least 6% since 2009. Bangladesh emerged as one of the fastest growing economies.

According to economist Syed Akhtar Mahmood, the Bangladeshi government is often seen as the villain in the country's economic story. But government has played an important role in stimulating the economy through building infrastructure, liberalizing regulations, and promoting high yielding crops in agriculture. According to Mahmood, "ost roads linking the villages with one another, and with the cities, were not paved and not accessible throughout the year. This situation was remarkably transformed within a span of 10 years, from 1988 to 1997, with the construction of the so-called feeder roads. In 1988, Bangladesh had about 3,000 kilometers of feeder roads. By 1997, this network expanded to 15,500 kilometers. These “last-mile” all-weather roads helped connect the villages of Bangladesh to the rest of the country".[103]

As a result of export-led growth, Bangladesh has enjoyed a trade surplus in recent years. Bangladesh historically has run a large trade deficit, financed largely through aid receipts and remittances from workers overseas.[101] Foreign reserves dropped markedly in 2001 but stabilised in the US$3 to US$4 billion range (or about 3 months' import cover).[101] In January 2007, reserves stood at $3.74 billion, and then increased to $5.8 billion by January 2008, in November 2009 it surpassed $10.0 billion, and as of April 2011 it surpassed the US$12 billion according to the Bank of Bangladesh, the central bank.[101] The dependence on foreign aid and imports has also decreased gradually since the early 1990s.[107] Foreign aid now accounts for only 2% of GDP.[108]

In the last decade, poverty dropped by around one third with significant improvements in the human development index, literacy, life expectancy and per capita food consumption. With the economy growing annually at an average rate of 6% over a prolonged period, more than 15 million people have moved out of poverty since 1992.[109] The poverty rate went down from 80% in 1971 to 44.2% in 1991 to 12.9% in 2021.[110][111][112] In recent years, Bangladesh has focused on promoting regional trade and transport links. The Bangladesh Bhutan India Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement seeks to create hassle free road transport across international borders.[113] Bangladesh also signed a coastal shipping agreement with India.[114] While prioritizing food security in the domestic market,[115] Bangladesh exports more than US$1 billion worth of processed food products.[116][117] As the result of a robust agricultural supply chain, supermarkets have sprung up in cities and towns across the country.

Bangladesh became the second largest textile exporter in the world.[118][119] An estimated 4.4 million workers are employed in the garments industry, with the majority being women.[120] The sector contributes 11% of Bangladesh's GDP.[121] The 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse caused global concern on industrial safety in Bangladesh, leading to the formation of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. The local clothing industry has seen fiercely competitive brands vying for the market, including Aarong, Westecs, Ecstasy, and Yellow among many others.

The World Bank notes the economic progress of the country by stating that "hen the newly independent country of Bangladesh was born on December 16, 1971, it was the second poorest country in the world—making the country's transformation over the next 50 years one of the great development stories. Since then, poverty has been cut in half at record speed. Enrolment in primary school is now nearly universal. Hundreds of thousands of women have entered the workforce. Steady progress has been made on maternal and child health. And the country is better buttressed against the destructive forces posed by climate change and natural disasters. Bangladesh's success comprises many moving parts—from investing in human capital to establishing macroeconomic stability. Building on this success, the country is now setting the stage for further economic growth and job creation by ramping up investments in energy, inland connectivity, urban projects, and transport infrastructure, as well as prioritizing climate change adaptation and disaster preparedness on its path toward sustainable growth".[122]

As of 2022, Bangladesh had the second largest foreign-exchange reserves in South Asia. In 2021, Bangladesh surpassed both India and Pakistan in terms of per capita income.[123][45] The country achieved 100% electricity coverage for households in 2022.[124][125][126] Megaprojects like the Padma Bridge, Dhaka Metro, Matarbari Port, and Karnaphuli Tunnel have been planned to stimulate economic activity. The completion of Padma Bridge was expected to boost Bangladeshi GDP by 1.23%.[127] During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bangladesh experienced pressure on its foreign exchange reserves due to rising import costs; this affected the country's electricity sector which relies on imported fuel; rising import prices also contributed to inflation.[128]

Macro-economic trend

This is a chart of trend of gross domestic product of Bangladesh at market prices estimated by the International Monetary Fund with figures in millions of Bangladeshi Taka. However, this reflects only the formal sector of the economy.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product (Million Taka) | US Dollar Exchange | Inflation Index (2000=100) |

Per Capita Income (as % of USA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 250,300 | 16.10 Taka | 20 | 1.79 |

| 1985 | 597,318 | 31.00 Taka | 36 | 1.19 |

| 1990 | 1,054,234 | 35.79 Taka | 58 | 1.16 |

| 1995 | 1,594,210 | 40.27 Taka | 78 | 1.12 |

| 2000 | 2,453,160 | 52.14 Taka | 100 | 0.97 |

| 2005 | 3,913,334 | 63.92 Taka | 126 | 0.95 |

| 2008 | 5,003,438 | 68.65 Taka | 147 | |

| 2015 | 17,295,665 | 78.15 Taka. | 196 | 2.48 |

| 2019 | 26,604,164 | 84.55 Taka. | 2.91 |

Mean wages were $0.58 per man-hour in 2009.

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2021 (with IMF staff estimates in 2022–2027).[129] Inflation below 5% is in green. The annual unemployment rate is extracted from the World Bank, although the International Monetary Fund find them unreliable.[130]

| Year | GDP

(in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 40.7 | 511.2 | 22.6 | 283.3 | n/a | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1982 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1983 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1984 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1985 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1986 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1987 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1988 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1989 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1990 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1991 | n/a | |||||||

| 1992 | n/a

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Foreign_trade_of_Bangladesh Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |