A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Current distribution of Indigenous peoples of the Americas | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Approximately 62 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11.8 - 23.2 million[1][2] | |

| 3.7 - 9.6 million[3] | |

| 6.4 million[4] | |

| 5.9 million[5] | |

| 4.1 million[6] | |

| 2.1 million[7] | |

| 1.9 million[8] | |

| 1.8 million[9] | |

| 1.7 million[10] | |

| 1.3 million[11] | |

| 1.3 million[12] | |

| 724,592[13] | |

| 698,114[14] | |

| 601,019[15] | |

| 443,847[16] | |

| 140,039[17] | |

| 104,143[18] | |

| 78,492[19] | |

| 76,452[20] | |

| 50,189[21] | |

| 36,507[22] | |

| 20,344[23] | |

| 19,839[24] | |

| ~19,000[25] | |

| 13,310[26] | |

| 3,280[27] | |

| 2,576[28] | |

| 1,394[29] | |

| 951[30] | |

| 327[31] | |

| 162[32] | |

| 8[33] | |

| Languages | |

| Numerous Indigenous American languages (both extant and extinct) Non-native European languages: Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, Danish, Dutch, and Russian (formerly in Alaska) | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Christianity (Catholic and Protestant) Minority: various Indigenous American religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Métis, Mestizos, Zambos, and Pardos Distantly related to some Indigenous Siberian peoples | |

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are groups of people native to a specific region that inhabited the Americas before the arrival of European settlers in the 15th century and the ethnic groups who continue to identify themselves with those peoples.[34]

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are diverse; some Indigenous peoples were historically hunter-gatherers, while others traditionally practice agriculture and aquaculture. In some regions, Indigenous peoples created pre-contact monumental architecture, large-scale organized cities, city-states, chiefdoms, states, kingdoms, republics, confederacies, and empires.[35] These societies had varying degrees of knowledge of engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, planting and irrigation, geology, mining, metallurgy, sculpture, and goldsmithing.

Many parts of the Americas are still populated by Indigenous peoples; some countries have sizeable populations, especially Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, and the United States. At least a thousand different Indigenous languages are spoken in the Americas, where there are also 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone. Several of these languages are recognized as official by several governments such as those in Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay and Greenland. Some, such as Quechua, Arawak, Aymara, Guaraní, Mayan, and Nahuatl, count their speakers in the millions. Whether contemporary Indigenous people live in rural communities or urban ones, many also maintain additional aspects of their cultural practices to varying degrees, including religion, social organization and subsistence practices. Like most cultures, over time, cultures specific to many Indigenous peoples have also evolved, preserving traditional customs but also adjusting to meet modern needs. Some Indigenous peoples still live in relative isolation from Western culture and a few are still counted as uncontacted peoples.[36] Indigenous peoples from the Americas have also formed diaspora communities outside the Western Hemisphere, namely in former colonial centers in Europe. A notable example is the sizable Greenlandic Inuit community in Denmark.[37] In the 20th and 21st centuries, Indigenous peoples from Suriname and French Guiana migrated to the Netherlands and France, respectively.[38][39]

In addition to Indigenous communities, the Americas are also home to millions of people of mixed Indigenous and European, as well as sometimes African or Asian descent, historically referred to as Mestizos in Spanish-speaking countries.[40][41] In many Latin American countries, people of partial Indigenous descent make up the majority or a significant component of the population, including in most of Central America, Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Chile, and Paraguay.[42][43] [44] In fact, based on estimates of ethnic cultural identification in Latin America[43], mestizos significantly outnumber Indigenous people in most Spanish-speaking countries. However, since Indigenous communities in the Americas are defined by cultural identification and kinship rather than ancestry or racial concepts, mestizos or mixed people are usually not counted among the Indigenous population unless they speak an Indigenous language and/or identify as part of a particular Indigenous culture. [45] Additionally, many people of wholly Indigenous descent who don't follow Indigenous traditions or speak an Indigenous language have been classified or self-identify as "mestizo" in Latin American societies as a result of assimilation into the dominant Hispanic culture. In recent years, the self-identified Indigenous population in many countries has increased as a result of these people reclaiming their heritage amid a rise in Indigenous lead movements for self determination and social justice.[46]

Terminology

Application of the term "Indian" originated with Christopher Columbus, who, in his search for India, thought that he had arrived in the East Indies.[47][48][49][50][51][52]

The islands came to be known as the "West Indies", a name that is still used to describe the islands. This led to the blanket term "Indies" and "Indians" (Spanish: indios; Portuguese: índios; French: indiens; Dutch: indianen) for the Indigenous inhabitants, which implied some kind of ethnic or cultural unity among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This unifying concept, codified in law, religion, and politics, was not originally accepted by the myriad groups of Indigenous peoples themselves but has since been embraced or tolerated by many over the last two centuries.[53] The term "Indian" generally does not include the culturally and linguistically distinct Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions of the Americas, including the Aleuts, Inuit, or Yupik peoples. These peoples entered the continent as a second, more recent wave of migration several thousand years later and have much more recent genetic and cultural commonalities with the Indigenous peoples of Siberia. However, these groups are nonetheless considered "Indigenous peoples of the Americas".[54]

The term Amerindian, a portmanteau of "American Indian", was coined in 1902 by the American Anthropological Association. It has been controversial ever since its creation. It was immediately rejected by some leading members of the Association, and, while adopted by many, it was never universally accepted.[55] While never popular in Indigenous communities themselves, it remains a preferred term among some anthropologists, notably in some parts of Canada and the English-speaking Caribbean.[56][57][58][59]

"Indigenous peoples in Canada" is used as the collective name for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.[60][61] The term Aboriginal peoples as a collective noun (also describing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) is a specific term of art used in some legal documents, including the Constitution Act, 1982.[62] Over time, as societal perceptions and government–indigenous relationships have shifted, many historical terms have changed definitions or been replaced as they have fallen out of favor.[63] The use of the term "Indian" is frowned upon because it represents the imposition and restriction of Indigenous peoples and cultures by the Canadian Government.[63] The terms "Native" and "Eskimo" are generally regarded as disrespectful (in Canada), and so are rarely used unless specifically required.[64] While "Indigenous peoples" is the preferred term, many individuals or communities may choose to describe their identity using a different term.[63][64]

The Métis people of Canada can be contrasted, for instance, to the Indigenous-European mixed-race mestizos (or caboclos in Brazil) of Hispanic America who, with their larger population (in most Latin American countries constituting either outright majorities, pluralities, or at the least large minorities), identify largely as a new ethnic group distinct from both Europeans and Indigenous, but still considering themselves a subset of the European-derived Hispanic or Brazilian peoplehood in culture and ethnicity (cf. ladinos).

Among Spanish-speaking countries, indígenas or pueblos indígenas ('Indigenous peoples') is a common term, though nativos or pueblos nativos ('native peoples') may also be heard; moreover, aborigen ('aborigine') is used in Argentina and pueblos originarios ('original peoples') is common in Chile. In Brazil, indígenas and povos originários ('Indigenous peoples') are common formal-sounding designations, while índio ('Indian') is still the more often heard term (the noun for the South-Asian nationality being indiano), but for the past 10 years has been considered offensive and pejorative.[citation needed] Aborígene and nativo are rarely used in Brazil in Indigenous-specific contexts (e.g., aborígene is usually understood as the ethnonym for Indigenous Australians). The Spanish and Portuguese equivalents to Indian, nevertheless, could be used to mean any hunter-gatherer or full-blooded Indigenous person, particularly to continents other than Europe or Africa—for example, indios filipinos.[citation needed]

Indigenous peoples of the United States are commonly known as Native Americans, Indians, as well as Alaska Natives.[clarification needed] The term "Indian" is still used in some communities and remains in use in the official names of many institutions and businesses in Indian Country.[65]

Name controversy

The various nations, tribes, and bands of Indigenous peoples of the Americas have differing preferences in terminology for themselves.[66] While there are regional and generational variations in which umbrella terms are preferred for Indigenous peoples as a whole, in general, most Indigenous peoples prefer to be identified by the name of their specific nation, tribe, or band.[66][67]

Early settlers often adopted terms that some tribes used for each other, not realizing these were derogatory terms used by enemies. When discussing broader subsets of peoples, naming has often been based on shared language, region, or historical relationship.[68] Many English exonyms have been used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Some of these names were based on foreign language terms used by earlier explorers and colonists, while others resulted from the colonists' attempts to translate or transliterate endonyms from the native languages. Other terms arose during periods of conflict between the colonists and Indigenous peoples.[69]

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been more vocal about how they want to be addressed, pushing to suppress the use of terms widely considered to be obsolete, inaccurate, or racist. During the latter half of the 20th century and the rise of the Indian rights movement, the United States federal government responded by proposing the use of the term "Native American", to recognize the primacy of Indigenous peoples' tenure in the nation.[70] As may be expected among people of over 400 different cultures in the US alone, not all of the people intended to be described by this term have agreed on its use or adopted it. No single group naming convention has been accepted by all Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Most prefer to be addressed as people of their tribe or nations when not speaking about Native Americans/American Indians as a whole.[71]

Since the 1970s, the word "Indigenous", which is capitalized when referring to people, has gradually emerged as a favored umbrella term. The capitalization is to acknowledge that Indigenous peoples have cultures and societies that are equal to Europeans, Africans, and Asians.[67][72] This has recently been acknowledged in the AP Stylebook.[73] Some consider it improper to refer to Indigenous people as "Indigenous Americans" or to append any colonial nationality to the term because Indigenous cultures existed before European colonization. Indigenous groups have territorial claims that are different from modern national and international borders, and when labeled as part of a country, their traditional lands are not acknowledged. Some who have written guidelines consider it more appropriate to describe an Indigenous person as "living in" or "of" the Americas, rather than calling them "American"; or simply calling them "Indigenous" without any addition of a colonial state.[74][75]

History

Peopling of the Americas

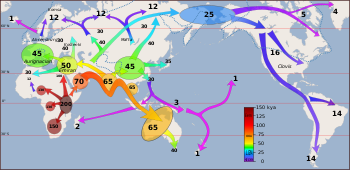

The peopling of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,000 to 19,000 years ago).[77] These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America, by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[78][79][80][81][82] The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.[83][84]

While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled from Asia, the pattern of migration and the place(s) of origin in Eurasia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remain unclear.[79] The traditional theory is that Ancient Beringians moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[85][86] following herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[87] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America as far as Chile.[88] Any archaeological evidence of coastal occupation during the last Ice Age would now have been covered by the sea level rise, up to a hundred metres since then.[89]

The precise date for the peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question, and while advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.[90][91] The "Clovis first theory" refers to the hypothesis that the Clovis culture represents the earliest human presence in the Americas about 13,000 years ago.[92] Evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated and pushed back the possible date of the first peopling of the Americas.[93][94][95][96] Academics generally believe that humans reached North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago.[90][93][97][98][99][100] Some new controversial archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.[93][101][102][103][104]Pre-Columbian era

While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus' voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of Indigenous cultures until Europeans either conquered or significantly influenced them.[108] "Pre-Columbian" is used especially often in the context of discussing the pre-contact Mesoamerican Indigenous societies: Olmec; Toltec; Teotihuacano' Zapotec; Mixtec; Aztec and Maya civilizations; and the complex cultures of the Andes: Inca Empire, Moche culture, Muisca Confederation, and Cañari.

The Pre-Columbian era refers to all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original arrival in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization during the early modern period.[109] The Norte Chico civilization (in present-day Peru) is one of the defining six original civilizations of the world, arising independently around the same time as that of Egypt.[110][111] Many later pre-Columbian civilizations achieved great complexity, with hallmarks that included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, engineering, astronomy, trade, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first significant European and African arrivals (ca. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through oral history and through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with the contact and colonization period and were documented in historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Mayan, Olmec, Mixtec, Aztec, and Nahua peoples, had their written languages and records. However, the European colonists of the time worked to eliminate non-Christian beliefs and burned many pre-Columbian written records. Only a few documents remained hidden and survived, leaving contemporary historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.

According to both Indigenous and European accounts and documents, American civilizations before and at the time of European encounter had achieved great complexity and many accomplishments.[112] For instance, the Aztecs built one of the largest cities in the world, Tenochtitlan (the historical site of what would become Mexico City), with an estimated population of 200,000 for the city proper and a population of close to five million for the extended empire.[113] By comparison, the largest European cities in the 16th century were Constantinople and Paris with 300,000 and 200,000 inhabitants respectively.[114] The population in London, Madrid, and Rome hardly exceeded 50,000 people. In 1523, right around the time of the Spanish conquest, the entire population in the country of England was just under three million people.[115] This fact speaks to the level of sophistication, agriculture, governmental procedure, and rule of law that existed in Tenochtitlan, needed to govern over such a large citizenry. Indigenous civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics, including the most accurate calendar in the world.[citation needed] The domestication of maize or corn required thousands of years of selective breeding, and continued cultivation of multiple varieties was done with planning and selection, generally by women.

Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Indigenous creation myths tell of a variety of origins of their respective peoples. Some were "always there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".[116]

European colonization

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Indigenous_people_of_the_AmericasText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk