A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

The history of Iran (or Persia, as it was commonly known in the Western world) is intertwined with that of Greater Iran, a sociocultural region spanning the area between Anatolia in the west and the Indus River and Syr Darya in the east, and between the Caucasus and Eurasian Steppe in the north and the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman in the south. Central to this area is the modern-day country of Iran, which covers the bulk of the Iranian plateau.

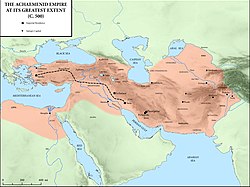

Iran is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilizations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC.[1] The south-western and western part of the Iranian plateau participated in the traditional ancient Near East with Elam (3200–539 BC), from the Bronze Age, and later with various other peoples, such as the Kassites, Mannaeans, and Gutians. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel calls the Persians the "first Historical People".[2] The Medes unified Iran as a nation and empire in 625 BC.[3] The Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC), founded by Cyrus the Great, ruled from the Balkans to North Africa and also Central Asia, spanning three continents, from their seat of power in Persis (Persepolis). It was the largest empire yet seen.[4] They were succeeded by the Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Empires, who successively governed Iran for almost 1,000 years and made Iran once again a leading power in the world. Persia's arch-rival was the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine Empire.

The Iranian Empire proper begins in the Iron Age, following the influx of Iranian peoples. Iranian people gave rise to the Medes, the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sasanian Empires of classical antiquity.

Once a major empire, Iran has endured invasions too, by the Macedonians, Arabs, Turks, and Mongols. Iran has continually reasserted its national identity throughout the centuries and has developed as a distinct political and cultural entity.

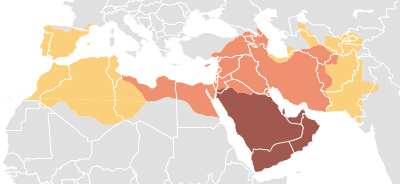

The Muslim conquest of Persia (632–654) ended the Sasanian Empire, and was a turning point in Iranian history. Islamization of Iran took place during the eighth to tenth centuries, leading to the eventual decline of Zoroastrianism in Iran as well as many of its dependencies. However, the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost but were to a great extent absorbed by the new Islamic polity and civilization.

Iran, with its long history of early cultures and empires, had suffered particularly hard during the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period. Many invasions of nomadic tribes, whose leaders became rulers in this country, affected it negatively.[5]

Iran was reunified as an independent state in 1501 by the Safavid dynasty, which set Shia Islam as the empire's official religion,[6] marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam.[7] Functioning again as a leading world power, this time amongst the neighbouring Ottoman Empire, its arch-rival for centuries, Iran had been a monarchy ruled by an emperor almost without interruption from 1501 until the 1979 Iranian Revolution, when Iran officially became an Islamic republic on 1 April 1979.[8][9]

Over the course of the first half of the 19th century, Iran lost many of its territories in the Caucasus, which had been a part of Iran for centuries,[10] comprising modern-day Eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Republic of Azerbaijan, and Armenia, to its rapidly expanding and emerging rival neighbor, the Russian Empire, following the Russo-Persian Wars between 1804–1813 and 1826–1828.[11]

Prehistory

Paleolithic

The earliest archaeological artifacts in Iran were found in the Kashafrud and Ganj Par sites that are thought to date back to 10,000 years ago in the Middle Paleolithic.[12] Mousterian stone tools made by Neanderthals have also been found.[13] There are more cultural remains of Neanderthals dating back to the Middle Paleolithic period, which mainly have been found in the Zagros region and fewer in central Iran at sites such as Kobeh, Kunji, Bisitun Cave, Tamtama, Warwasi, and Yafteh Cave.[14] In 1949, a Neanderthal radius was discovered by Carleton S. Coon in Bisitun Cave.[15] Evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic periods are known mainly from the Zagros Mountains in the caves of Kermanshah and Khorramabad and a few number of sites in Piranshahr and Alborz and Central Iran. During this time, people began creating rock art.[citation needed]

Neolithic to Chalcolithic

Early agricultural communities such as Chogha Golan in 10,000 BC[16][17] along with settlements such as Chogha Bonut (the earliest village in Elam) in 8000 BC,[18][19] began to flourish in and around the Zagros Mountains region in western Iran.[20] Around about the same time, the earliest-known clay vessels and modelled human and animal terracotta figurines were produced at Ganj Dareh, also in western Iran.[20] There are also 10,000-year-old human and animal figurines from Tepe Sarab in Kermanshah Province among many other ancient artefacts.[21]

The south-western part of Iran was part of the Fertile Crescent where most of humanity's first major crops were grown, in villages such as Susa (where a settlement was first founded possibly as early as 4395 cal BC)[22]: 46–47 and settlements such as Chogha Mish, dating back to 6800 BC;[23][24] there are 7,000-year-old jars of wine excavated in the Zagros Mountains[25] (now on display at the University of Pennsylvania) and ruins of 7000-year-old settlements such as Tepe Sialk are further testament to that. The two main Neolithic Iranian settlements were Ganj Dareh and the hypothetical Zayandeh River Culture.[26]

Bronze Age

Parts of what is modern-day northwestern Iran was part of the Kura–Araxes culture (circa 3400 BC—ca. 2000 BC), that stretched up into the neighbouring regions of the Caucasus and Anatolia.[27][28]

Susa is one of the oldest-known settlements of Iran and the world. Based on C14 dating, the time of the foundation of the city is as early as 4395 BC,[22]: 45–46 a time right after the establishment of the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk in 4500 BC. The general perception among archaeologists is that Susa was an extension of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, hence incorporating many aspects of Mesopotamian culture.[29][30] In its later history, Susa became the capital of Elam, which emerged as a state founded 4000 BC.[22]: 45–46 There are also dozens of prehistoric sites across the Iranian plateau pointing to the existence of ancient cultures and urban settlements in the fourth millennium BC.[23] One of the earliest civilizations on the Iranian plateau was the Jiroft culture in southeastern Iran in the province of Kerman.

It is one of the most artefact-rich archaeological sites in the Middle East. Archaeological excavations in Jiroft led to the discovery of several objects belonging to the 4th millennium BC.[31] There is a large quantity of objects decorated with highly distinctive engravings of animals, mythological figures, and architectural motifs. The objects and their iconography are considered unique. Many are made from chlorite, a grey-green soft stone; others are in copper, bronze, terracotta, and even lapis lazuli. Recent excavations at the sites have produced the world's earliest inscription which pre-dates Mesopotamian inscriptions.[32][33]

There are records of numerous other ancient civilizations on the Iranian plateau before the emergence of Iranian peoples during the Early Iron Age. The Early Bronze Age saw the rise of urbanization into organized city-states and the invention of writing (the Uruk period) in the Near East. While Bronze Age Elam made use of writing from an early time, the Proto-Elamite script remains undeciphered, and records from Sumer pertaining to Elam are scarce.

Russian historian Igor M. Diakonoff stated that the modern inhabitants of Iran are descendants of mainly non-Indo-European groups, more specifically of pre-Iranic inhabitants of the Iranian Plateau: "It is the autochthones of the Iranian plateau, and not the Proto-Indo-European tribes of Europe, which are, in the main, the ancestors, in the physical sense of the word, of the present-day Iranians."[34]

Early Iron Age

Records become more tangible with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its records of incursions from the Iranian plateau. As early as the 20th century BC, tribes came to the Iranian plateau from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. The arrival of Iranians on the Iranian plateau forced the Elamites to relinquish one area of their empire after another and to take refuge in Elam, Khuzestan and the nearby area, which only then became coterminous with Elam.[35] Bahman Firuzmandi say that the southern Iranians might be intermixed with the Elamite peoples living in the plateau.[36] By the mid-first millennium BC, Medes, Persians, and Parthians populated the Iranian plateau. Until the rise of the Medes, they all remained under Assyrian domination, like the rest of the Near East. In the first half of the first millennium BC, parts of what is now Iranian Azerbaijan were incorporated into Urartu.

Classical antiquity

Median and Achaemenid Empire (680–330 BC)

-

The tomb of Cyrus the Great

-

Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis

-

Ruins of the Apadana, Persepolis

-

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis

In 646 BC, Assyrian king Ashurbanipal sacked Susa, which ended Elamite supremacy in the region.[37] For over 150 years Assyrian kings of nearby Northern Mesopotamia had been wanting to conquer Median tribes of Western Iran.[38] Under pressure from Assyria, the small kingdoms of the western Iranian plateau coalesced into increasingly larger and more centralized states.[37]

In the second half of the seventh century BC, the Medes gained their independence and were united by Deioces. In 612 BC, Cyaxares, Deioces' grandson, and the Babylonian king Nabopolassar invaded Assyria and laid siege to and eventually destroyed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, which led to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[39] Urartu was later on conquered and dissolved as well by the Medes.[40][41] The Medes are credited with founding Iran as a nation and empire, and established the first Iranian empire, the largest of its day until Cyrus the Great established a unified empire of the Medes and Persians, leading to the Achaemenid Empire (c.550–330 BC).

Cyrus the Great overthrew, in turn, the Median, Lydian, and Neo-Babylonian Empires, creating an empire far larger than Assyria. He was better able, through more benign policies, to reconcile his subjects to Persian rule; the longevity of his empire was one result. The Persian king, like the Assyrian, was also "King of Kings", xšāyaθiya xšāyaθiyānām (shāhanshāh in modern Persian) – "great king", Megas Basileus, as known by the Greeks.

Cyrus's son, Cambyses II, conquered the last major power of the region, ancient Egypt, causing the collapse of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt. Since he became ill and died before, or while, leaving Egypt, stories developed, as related by Herodotus, that he was struck down for impiety against the ancient Egyptian deities. After the death of Cambyses II, Darius ascended the throne by overthrowing the legitimate Achaemenid monarch Bardiya, and then quelling rebellions throughout his kingdom. As the winner, Darius I, based his claim on membership in a collateral line of the Achaemenid Empire.

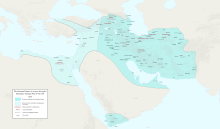

Darius' first capital was at Susa, and he started the building program at Persepolis. He rebuilt a canal between the Nile and the Red Sea, a forerunner of the modern Suez Canal. He improved the extensive road system, and it is during his reign that mentions are first made of the Royal Road (shown on map), a great highway stretching all the way from Susa to Sardis with posting stations at regular intervals. Major reforms took place under Darius. Coinage, in the form of the daric (gold coin) and the shekel (silver coin) was standardized (coinage had already been invented over a century before in Lydia c. 660 BC but not standardized),[42] and administrative efficiency increased.

The Old Persian language appears in royal inscriptions, written in a specially adapted version of the cuneiform script. Under Cyrus the Great and Darius I, the Persian Empire eventually became the largest empire in human history up until that point, ruling and administrating over most of the then known world,[43] as well as spanning the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa. The greatest achievement was the empire itself. The Persian Empire represented the world's first superpower[44][45] that was based on a model of tolerance and respect for other cultures and religions.[46]

In the late sixth century BC, Darius launched his European campaign, in which he defeated the Paeonians, conquered Thrace, and subdued all coastal Greek cities, as well as defeating the European Scythians around the Danube river.[47] In 512/511 BC, Macedon became a vassal kingdom of Persia.[47]

In 499 BC, Athens lent support to a revolt in Miletus, which resulted in the sacking of Sardis. This led to an Achaemenid campaign against mainland Greece known as the Greco-Persian Wars, which lasted the first half of the 5th century BC, and is known as one of the most important wars in European history. In the First Persian invasion of Greece, the Persian general Mardonius re-subjugated Thrace and made Macedon a full part of Persia.[47] The war eventually turned out in defeat, however. Darius' successor Xerxes I launched the Second Persian invasion of Greece. At a crucial moment in the war, about half of mainland Greece was overrun by the Persians, including all territories to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth,[48][49] however, this was also turned out in a Greek victory, following the battles of Plataea and Salamis, by which Persia lost its footholds in Europe, and eventually withdrew from it.[50] During the Greco-Persian wars, the Persians gained major territorial advantages. They captured and razed Athens twice, once in 480 BC and again in 479 BC. However, after a string of Greek victories the Persians were forced to withdraw, thus losing control of Macedonia, Thrace and Ionia. Fighting continued for several decades after the successful Greek repelling of the Second Invasion with numerous Greek city-states under the Athens' newly formed Delian League, which eventually ended with the peace of Callias in 449 BC, ending the Greco-Persian Wars. In 404 BC, following the death of Darius II, Egypt rebelled under Amyrtaeus. Later pharaohs successfully resisted Persian attempts to reconquer Egypt until 343 BC, when Egypt was reconquered by Artaxerxes III.

Greek conquest and Seleucid Empire (312 BC–248 BC)

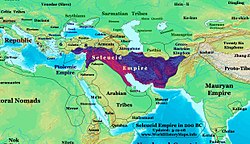

From 334 BC to 331 BC, Alexander the Great defeated Darius III in the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, swiftly conquering the Persian Empire by 331 BC. Alexander's empire broke up shortly after his death, and Alexander's general, Seleucus I Nicator, tried to take control of Iran, Mesopotamia, and later Syria and Anatolia. His empire was the Seleucid Empire. He was killed in 281 BC by Ptolemy Keraunos.

Greek language, philosophy, and art came with the colonists. During the Seleucid era, Greek became the common tongue of diplomacy and literature throughout the empire.

Parthian Empire (248 BC–224 AD)

The Parthian Empire—ruled by the Parthians, a group of northwestern Iranian people—was the realm of the Arsacid dynasty. This latter reunited and governed the Iranian plateau after the Parni conquest of Parthia and defeating the Seleucid Empire in the late third century BC. It intermittently controlled Mesopotamia between c. 150 BC and 224 AD and absorbed Eastern Arabia.

Parthia was the eastern arch-enemy of the Roman Empire and it limited Rome's expansion beyond Cappadocia (central Anatolia). The Parthian armies included two types of cavalry: the heavily armed and armored cataphracts and the lightly armed but highly-mobile mounted archers.

For the Romans, who relied on heavy infantry, the Parthians were too hard to defeat, as both types of cavalry were much faster and more mobile than foot soldiers. The Parthian shot used by the Parthian cavalry was most notably feared by the Roman soldiers, which proved pivotal in the crushing Roman defeat at the Battle of Carrhae. On the other hand, the Parthians found it difficult to occupy conquered areas as they were unskilled in siege warfare. Because of these weaknesses, neither the Romans nor the Parthians were able completely to annex each other's territory.

The Parthian empire subsisted for five centuries, longer than most Eastern Empires. The end of this empire came at last in 224 AD, when the empire's organization had loosened and the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassal peoples, the Persians under the Sasanians. However, the Arsacid dynasty continued to exist for centuries onwards in Armenia, the Iberia, and the Caucasian Albania, which were all eponymous branches of the dynasty.

Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD)

The first shah of the Sasanian Empire, Ardashir I, started reforming the country economically and militarily. For a period of more than 400 years, Iran was once again one of the leading powers in the world, alongside its neighbouring rival, the Roman and then Byzantine Empires.[51][52] The empire's territory, at its height, encompassed all of today's Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Abkhazia, Dagestan, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, parts of Afghanistan, Turkey, Syria, parts of Pakistan, Central Asia, Eastern Arabia, and parts of Egypt.

Most of the Sasanian Empire's lifespan was overshadowed by the frequent Byzantine–Sasanian wars, a continuation of the Roman–Parthian Wars and the all-comprising Roman–Persian Wars; the last was the longest-lasting conflict in human history. Started in the first century BC by their predecessors, the Parthians, and Romans, the last Roman–Persian War was fought in the seventh century. The Persians defeated the Romans at the Battle of Edessa in 260 and took emperor Valerian prisoner for the remainder of his life.

Eastern Arabia was conquered early on. During Khosrow II's rule in 590–628, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine and Lebanon were also annexed to the Empire. The Sassanians called their empire Erânshahr ("Dominion of the Aryans", i.e., of Iranians).[53]

A chapter of Iran's history followed after roughly six hundred years of conflict with the Roman Empire. During this time, the Sassanian and Romano-Byzantine armies clashed for influence in Anatolia, the western Caucasus (mainly Lazica and the Kingdom of Iberia; modern-day Georgia and Abkhazia), Mesopotamia, Armenia and the Levant. Under Justinian I, the war came to an uneasy peace with payment of tribute to the Sassanians.

However, the Sasanians used the deposition of the Byzantine emperor Maurice as a casus belli to attack the Empire. After many gains, the Sassanians were defeated at Issus, Constantinople, and finally Nineveh, resulting in peace. With the conclusion of the over 700 years lasting Roman–Persian Wars through the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, which included the very siege of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, the war-exhausted Persians lost the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah (632) in Hilla (present-day Iraq) to the invading Muslim forces.

The Sasanian era, encompassing the length of Late Antiquity, is considered to be one of the most important and influential historical periods in Iran, and had a major impact on the world. In many ways, the Sassanian period witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization and constitutes the last great Iranian Empire before the adoption of Islam. Persia influenced Roman civilization considerably during Sassanian times,[54] their cultural influence extending far beyond the empire's territorial borders, reaching as far as Western Europe,[55] Africa,[56] China and India[57] and also playing a prominent role in the formation of both European and Asiatic medieval art.[58]

This influence carried forward to the Muslim world. The dynasty's unique and aristocratic culture transformed the Islamic conquest and destruction of Iran into a Persian Renaissance.[55] Much of what later became known as Islamic culture, architecture, writing, and other contributions to civilization, were taken from the Sassanian Persians into the broader Muslim world.[59]

Medieval period

Early Islamic period

Islamic conquest of Persia (633–651)

In 633, when the Sasanian king Yazdegerd III was ruling over Iran, the Muslims under Umar invaded the country right after it had been in a bloody civil war. Several Iranian nobles and families such as king Dinar of the House of Karen, and later Kanarangiyans of Khorasan, mutinied against their Sasanian overlords. Although the House of Mihran had claimed the Sasanian throne under the two prominent generals Bahrām Chōbin and Shahrbaraz, it remained loyal to the Sasanians during their struggle against the Arabs, but the Mihrans were eventually betrayed and defeated by their own kinsmen, the House of Ispahbudhan, under their leader Farrukhzad, who had mutinied against Yazdegerd III.

Yazdegerd III fled from one district to another until a local miller killed him for his purse at Merv in 651.[60] By 674, Muslims had conquered Greater Khorasan (which included modern Iranian Khorasan province and modern Afghanistan and parts of Transoxiana).

The Muslim conquest of Persia ended the Sasanian Empire and led to the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. Over time, the majority of Iranians converted to Islam. Most of the aspects of the previous Persian civilizations were not discarded but were absorbed by the new Islamic polity. As Bernard Lewis has commented:

"These events have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders. Both perceptions are of course valid, depending on one's angle of vision."[61]

Umayyad era and Muslim incursions into the Caspian coast

After the fall of the Sasanian Empire in 651, the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate adopted many Persian customs, especially the administrative and the court mannerisms. Arab provincial governors were undoubtedly either Persianized Arameans or ethnic Persians; certainly Persian remained the language of official business of the caliphate until the adoption of Arabic toward the end of the seventh century,[62] when in 692 minting began at the capital, Damascus. The new Islamic coins evolved from imitations of Sasanian coins (as well as Byzantine), and the Pahlavi script on the coinage was replaced with Arabic alphabet.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Medieval_Persia

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk