A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Employees of the now-defunct newspaper News of the World engaged in phone hacking, police bribery, and exercising improper influence in the pursuit of stories.

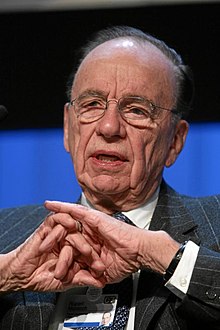

Investigations conducted from 2005 to 2007 showed that the paper's phone hacking activities were targeted at celebrities, politicians, and members of the British royal family. In July 2011 it was revealed that the phones of murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler, relatives of deceased British soldiers, and victims of the 7 July 2005 London bombings had also been hacked. The resulting public outcry against News Corporation and its owner, Rupert Murdoch, led to several high-profile resignations, including that of Murdoch as News Corporation director, Murdoch's son James as executive chairman, Dow Jones chief executive Les Hinton, News International legal manager Tom Crone, and chief executive Rebekah Brooks. The commissioner of London's Metropolitan Police, Sir Paul Stephenson, also resigned. Advertiser boycotts led to the closure of the News of the World on 10 July 2011, after 168 years of publication.[1] Public pressure forced News Corporation to cancel its proposed takeover of the British satellite broadcaster BSkyB.

The prime minister, David Cameron, announced on 6 July 2011 that a public inquiry, known as the Leveson Inquiry, would look into phone hacking and police bribery by the News of the World and consider the wider culture and ethics of the British newspaper industry, and that the Press Complaints Commission would be replaced "entirely".[1][2] A number of arrests and convictions followed, most notably of the former News of the World managing editor Andy Coulson.

Murdoch and his son, James, were summoned to give evidence at the Leveson Inquiry. Over the course of his testimony, Rupert Murdoch admitted that a cover-up had taken place within the News of the World to hide the scope of the phone hacking.[3] On 1 May 2012, a parliamentary select committee report concluded that the elder Murdoch "exhibited wilful blindness to what was going on in his companies and publications" and stated that he was "not a fit person to exercise the stewardship of a major international company".[4] On 3 July 2013, Channel 4 News broadcast a secret tape from earlier that year, in which Murdoch dismissively claims that investigators were "totally incompetent" and acted over "next to nothing" and excuses his papers' actions as "part of the culture of Fleet Street".[5]

Early investigations, 1990s–2005

By 2002, an organised trade in confidential personal information had developed in Britain and was widely used by the British newspaper industry.[6][7] Illegal means of gaining information used included hacking the private voicemail accounts on mobile phones, hacking into computers, making false statements to officials, entrapment, blackmail, burglaries, theft of mobile phones and making payments to public officials.[8][9][10][11][12]

Operation Nigeria

Private investigators who were illegally providing information to the News of the World were also engaged in a variety of other illegal activities. Between 1999 and 2003, several were convicted for crimes including drug distribution, the theft of drugs, child pornography, planting evidence, corruption, and perverting the course of justice. Jonathan Rees and his partner Sid Fillery, a former police officer, were also under suspicion for the murder of private investigator Daniel Morgan. The Metropolitan Police Service undertook an investigation of Rees, entitled Operation Nigeria, and tapped his telephone. Substantial evidence was accumulated that Rees was purchasing information from improper sources and that, amongst others, Alex Marunchak of the News of the World was paying him up to £150,000 a year for doing so.[13] Jonathan Rees reportedly bought information from former and serving police officers, Customs officers, a VAT inspector, bank employees, burglars, and from blaggers who would telephone the Inland Revenue, the DVLA, banks and phone companies, and deceive them into releasing confidential information.[11] Rees then sold the information to the News of the World, the Daily Mirror, the Sunday Mirror and the Sunday Times.[14]

The Operation Nigeria bugging ended in September 1999 and Rees was arrested when he was heard planning to plant drugs on a woman so that her husband could win custody of their child.[13][15] Rees was convicted in 2000 and served a five-year prison sentence.[13][16] Other individuals associated with Rees who were taped during Operation Nigeria, including Detective Constable Austin Warnes, former detective Duncan Hanrahan, former Detective Constable Martin King and former Detective Constable Tom Kingston, were prosecuted and jailed for various offences unrelated to phone hacking.[13][15][17]

In June 2002, Fillery had reportedly used his relationship with Alex Marunchak to arrange for private investigator Glenn Mulcaire, then doing work for News of the World, to obtain confidential information about Detective Chief Superintendent David Cook, one of the police officers investigating the murder of Daniel Morgan. Mulcaire obtained Cook's home address, his internal Metropolitan police payroll number, his date of birth and figures for his mortgage payments as well as physically following him and his family. Attempts to access Cook's voicemail and that of his wife, and possibly hack his computer and intercept his post were also suspected.[18] Documents reportedly held by Scotland Yard show that "Mulcaire did this on the instructions of Greg Miskiw, assistant editor at News of the World and a close friend of Marunchak." The Metropolitan Police Service handled this apparent attempt by agents of the News of the World to interfere with a murder inquiry by having informal discussions with Rebekah Brooks, then editor for the newspaper. "Scotland Yard took no further action, apparently reflecting the desire of Dick Fedorcio, Director of Public Affairs and Internal Communication for the Met who had a close working relationship with Brooks, to avoid unnecessary friction with the newspaper."[18]

No one was charged with illegal acquisition of confidential information as a result of Operation Nigeria, even though the Met reportedly collected hundreds of thousands of incriminating documents during the investigation into Jonathan Rees and his links with corrupt officers.[19][20] Fillery was convicted for child pornography offences in 2003.[16] Upon Rees' release from prison in 2005, he immediately resumed his investigative work for the News of the World, where Andy Coulson had succeeded Rebekah Brooks as editor.

Operation Motorman

In 2002, under the title Operation Motorman, the Information Commissioner's Office[21] raided the offices of various newspapers and private investigators, looking for details of personal information kept on unregistered computer databases. The operation uncovered numerous invoices addressed to newspapers and magazines, which detailed prices for the provision of personal information. A total of 305 journalists, working for at least 30 publications, were identified as purchasing confidential information from private investigators.[6][22] The ICO raided a private investigator named John Boyall, whose specialty was acquiring information from confidential databases. Glenn Mulcaire had been Boyall's assistant, until the autumn of 2001 when the News of the World's assistant editor, Greg Miskiw gave him a full-time contract to do work for the newspaper.[13] When the ICO raided Boyall's premises in November 2002 they seized documents that led them to the premises of another private investigator, Steve Whittamore.[23][24] There they found "more than 13,000 requests for confidential information from newspapers and magazines".[13][18] This established that confidential information was illegally acquired from telephone companies, the Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency and the Police National Computer. "Media, especially newspapers, insurance companies and local authorities chasing council tax arrears all appear in the sales ledger" of the agency.[23] Whittamore's network gave him access to confidential records at telephone companies, banks, post offices, hotels, theatres, and prisons, including BT Group, Crédit Lyonnais, Goldman Sachs, Hang Seng Bank, Glen Parva prison, and Stocken prison.[24]

Although the ICO issued two reports, "What price privacy?" in May 2006 and "What price privacy now?" in December 2006, much of the information obtained through Operation Motorman was not made public.[23][25] Although there was evidence of many people being engaged in illegal activity, relatively few were questioned. Operation Motorman's lead investigator said in 2006 that "his team were told not to interview journalists involved. The investigator ... accused authorities of being too 'frightened' to tackle journalists."[26] The newspaper with the highest number of requests was the Daily Mail with 952 transactions by 58 journalists; the News of the World came fifth in the table, with 182 transactions from 19 journalists.[22] The Daily Mail rejected the accusations within the report insisting it only used private investigators to confirm public information, such as dates of birth.[22]

Operation Glade

Learning that Steve Whittamore was obtaining information from the police national computer, the Information Commissioner contacted the Metropolitan Police and the Met's anti-corruption unit initiated Operation Glade.[13] Whittamore's detailed records identified 27 different journalists as having commissioned him to acquire confidential information for which they paid him tens of thousands of pounds. Invoices submitted to News International "sometimes made explicit reference to obtaining a target's details from their phone number or their vehicle registration".[24] Between February 2004 and April 2005, the Crown Prosecution Service charged ten men working for private detective agencies with crimes relating to the illegal acquisition of confidential information.[13][27][28] No journalists were charged.[28] Whittamore, Boyall, and two others pleaded guilty in April 2005. According to ICO head Richard Thomas, "each pleaded guilty yet, despite the extent and the frequency of their admitted criminality, each was conditionally discharged , raising important questions for public policy."[13][23]

2005–2006: Royal phone hacking scandal

On 14 November 2005, the News of the World published an article written by royal editor Clive Goodman that claimed Prince William was in the process of borrowing a portable editing suite from ITV correspondent Tom Bradby. Following the publication, the Prince and Bradby met to try to figure out how the details of their arrangement had been leaked, as only two other people were aware of it. Prince William noted that another equally improbable leak had recently taken place regarding an appointment he had made with a knee surgeon.[29] The Prince and Bradby concluded it was likely that their voicemails were being accessed.[30]

The Metropolitan Police set up an investigation under Deputy Assistant Commissioner Peter Clarke reporting to Assistant Commissioner Andy Hayman, commander of the Specialist Operations directorate, which included royal protection.[31][32] By January 2006, Clarke's team had concluded that the compromised voice mail accounts belonged to Prince William's aides, not the Prince himself, and that there was an "unambiguous trail" to Clive Goodman, the News of the World royal reporter, and to Glenn Mulcaire, a private investigator.[33] The detectives put Goodman and Mulcaire under surveillance and, on 8 August 2006, searched Goodman's desk at the News of the World and raided Mulcaire's home. There they seized "11,000 pages of handwritten notes listing nearly 4,000 celebrities, politicians, sports stars, police officials and crime victims whose phones may have been hacked."[34][35][36] The names included eight members of the royal family and their staff.[35] There were dozens of notebooks, two computers containing 2,978 complete or partial mobile phone numbers and 91 PIN codes, plus 30 tape recordings made by Mulcaire. Significantly, there were at least three names of News of the World journalists other than Goodman and a recording of Mulcaire instructing a journalist how to hack into private voice mail.[35][36] All of this material was taken to Scotland Yard.

In August 2006, Goodman and Mulcaire were arrested by the Metropolitan Police, and later charged with hacking the telephones of members of the royal family by accessing voicemail messages, an offence under section 79 of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000.[37] The News of the World had paid Mulcaire £104,988 for his services. In addition, Goodman had paid Mulcaire £12,300 in cash between 9 November 2005 and 7 August 2006, using the code name Alexander on his expenses sheet for him.[38] The court heard that Mulcaire had also hacked into the messages of supermodel Elle Macpherson, former publicist Max Clifford, MP Simon Hughes, football agent Sky Andrew, and Gordon Taylor.[33] On 26 January 2007, both Goodman and Mulcaire pleaded guilty to the charges and were sentenced to four and six months imprisonment respectively.[39] On the same day, Andy Coulson resigned as editor of the News of the World, while insisting that he had no knowledge of any illegal activities. In March 2007, a senior aide to Rupert Murdoch told a parliamentary committee that a "rigorous internal investigation" found no evidence of widespread hacking at the News of the World.

After Goodman and Mulcaire pleaded guilty, a breach of privacy claim was started by Gordon Taylor, chief executive of the Professional Footballers Association who was represented by his solicitor Mark Lewis.[40] That claim settled for a payment of £700,000 including legal costs.[41] James Murdoch agreed to the settlement.[42]

PCC investigations

The Press Complaints Commission, PCC, was the organisation charged with self-regulation of the newspaper and magazine industry in Britain. The PCC's inquiry into phone hacking in 2007 concluded that the practice should stop but that "there is a legitimate place for the use of subterfuge when there are grounds in the public interest to use it and it is not possible to obtain information through other means".[43][44] News of the World editor Colin Myler told the PCC that Goodman's hacking was "aberrational", "a rogue exception" of a single journalist. The PCC opted not to question Andy Coulson on the grounds that he had left the industry, and not to question any other journalist or executive on the paper, apart from Myler, who had no knowledge of what had been going on there before his appointment. The PCC's subsequent report failed to uncover any evidence of any phone hacking by any newspaper beyond that revealed at Goodman's trial.[45]

In 2009 the PCC held another inquiry, to see whether they were misled by the News of the World in 2007, and if there was any evidence that phone hacking had taken place since then. It concluded it had not been misled and that there was no evidence of ongoing phone hacking.[46] This report and its conclusions were withdrawn on 6 July 2011, two days after it was revealed that Milly Dowler's phone had been hacked.[47][48][49]

2009–2011: Renewed investigations

After the 2006 conviction of Clive Goodman and Glenn Mulcaire, and with assurances from News International, the Press Complaints Commission and the Metropolitan Police Service that no one else had been involved in phone hacking, the public perception was that the matter was closed. Nick Davies and other journalists from The Guardian, and eventually other newspapers, continued to examine evidence from court cases and use Freedom of Information Act 2000 requests to find evidence to the contrary.[50][51]

The Guardian July 2009 reports

A small number of victims of phone hacking engaged solicitors and made civil claims for invasion of privacy. By March 2010, News International had spent over £2 million settling court cases with victims of phone hacking. As information about these claims leaked out, The Guardian continued to follow the story. On 8 & 9 July 2009, the newspaper published three articles alleging that:

- News Group Newspapers, NGN, a subsidiary of News International, agreed to large settlements with hacking victims, including Gordon Taylor. The settlements included gagging provisions to prevent release of evidence that NGN journalists had used criminal methods to get stories. "News Group then persuaded the court to seal the file on Taylor's case to prevent all public access, even though it contained prima facie evidence of criminal activity."[52] That evidence included documents seized in raids by the Information Commissioner's Office as well as by the Met.[45]

- If the suppressed evidence became public, hundreds more phone hacking victims might be able to take legal action against News International newspapers and might lead to police inquiries being re-opened.[52]

- When Andy Coulson was editor of the News of the World, journalists there openly engaged private investigators for illegal phone hacking and raised invoices that itemised illegal acts.[45]

- Everybody at the News of the World knew what was going on and knew that there was no public interest defense for phone hacking. The way investigations had been pursued raised serious questions about the Metropolitan Police, the Crown Prosecution Service, and the courts which, "faced with evidence of conspiracy and systemic illegal actions,... agreed to seal the evidence." rather than make it public.[53]

- The Met held evidence that thousands of mobile phones had been hacked into by agents of the News of the World and that Members of Parliament, including cabinet ministers, were among the victims.[52]

- "The Metropolitan Police took the decision not to inform all the individuals whose phones had been targeted and the Crown Prosecution Service decided not to take News Group executives to court."[45]

- News International executives had misled a Parliamentary select committee, the Press Complaints Commission and the public about the extent of their newspaper's illegal activities.[52]

Scotland Yard's response

When the Guardian articles were published, Metropolitan Police Service Commissioner Sir Paul Stephenson asked Assistant Commissioner John Yates to look at the phone hacking case to see if it should be reopened. Yates reportedly took just eight hours to consult with senior detectives and Crown Prosecution lawyers to conclude there was no fresh material that could lead to further convictions.[54] His review did not include an examination of the thousands of pages of evidence seized in the 2006 Mulcaire raid.[55] In September 2009, Yates maintained his position to the Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee saying, "There remain now insufficient grounds or evidence to arrest or interview anyone else and... no additional evidence has come to light."[56] Upon review of the first inquiry, he concluded that there were "hundreds, not thousands of potential victims".[34] Yates told the Committee, "It is very few, it is a handful" of persons that had been subject to hacking.[57] Although Yates was aware of the "Transcript for Neville" email that indicated more than a single rogue reporter was involved, he did not interview Neville Thurlbeck nor any other journalist at the News of the World, nor look into the cases of victims beyond the eight named in court in 2006.[57][58] The Committee's findings, released in February 2010, were critical of the police for not pursuing "evidence that merited a wider investigation".[36][59]

The Committee Chairman John Whittingdale also questioned whether the Committee had been misled by several of the News International executives who had testified before it in 2007 that Goodman alone was involved in phone hacking. The Committee again heard evidence from Les Hinton, by then chief executive officer of Dow Jones & Company, and Andy Coulson, by then director of communications for the Conservative Party. Their report concluded that it was "inconceivable" that no one, other than Goodman, knew about the extent of phone hacking at the paper, and that the Committee had "repeatedly encountered an unwillingness to provide the detailed information that we sought, claims of ignorance or lack of recall and deliberate obfuscation".[59]

Assistant Commissioner Yates returned to the Committee on 24 March 2011 and defended his position that only ten to twelve victims met the criteria given to the police by the Crown Prosecution Service. The CPS denied that what they had told the Met could be reasonably used to limit the scope of the investigation.[60] Further, they claimed to have been misled by the Met during consultations on the Royal Household inquiry. Met officials reportedly "didn't discuss certain evidence with senior prosecutors, including the notes suggesting the involvement of other reporters."[36]

The Home Affairs Select Committee also questioned Yates in 2009 about the Met's continuing refusal to reopen the investigation "following allegations that 27 other News International reporters had commissioned private investigators to carry out tasks, some of which might have been illegal." Yates responded that he had only looked into the facts of the original 2006 inquiry into Goodmans activities.[61] The Home Affairs Committee began another inquiry on 1 September 2010 and later published a report highly critical of the Met, stating, "The difficulties were offered to us as justifying a failure to investigate further, and we saw nothing that suggested there was a real will to tackle and overcome those obstacles."

The Guardian continued to be critical of Yates, who responded by hiring a firm of libel lawyers, paid for by the Met, to threaten legal action against anyone that claimed he had misled Parliament.[13][62] Eventually, as celebrities and politicians continued asking if they had been victims of hacking, Yates directed that the evidence from the Mulcaire raid, that had been stored in bin bags for three years, finally be entered into a computer database. Ten people were assigned the task. Yates himself did not look at the evidence saying later, "I'm not going to go down and look at bin bags. I am supposed to be an Assistant Commissioner."[55] He did not re-open the investigation.

Days after the settlement with Gordon Taylor was revealed by The Guardian in July 2009, Max Clifford, another of the eight victims named in 2006, announced his intentions to sue. In March 2010, News International agreed to settle his suit for £1,000,000, a much greater than expected settlement if hacking Clifford's phone was the only issue.[63] These two awards encouraged other victims to explore legal redress, resulting in more and more phone hacking queries to the Metropolitan Police, which they were often slow to respond to.[64] One commentator observed that "the Goodman-Mulcaire revelations and subsequent prosecution were supposed to have settled the hacking matter forever and might have done just that, except that successful law suits... kept popping up against News of the World after the convictions."[65]

The Guardian December 2010 report

On 15 December 2010, The Guardian reported that some of the documents seized from Glenn Mulcaire in 2006 by the Metropolitan Police Service and only recently disclosed in open court, implied that News of the World editor Ian Edmondson specifically instructed Mulcaire to hack voice messages of Sienna Miller, Jude Law, and several others. The documents also implied that Mulcaire was engaged by News of the World chief reporter Neville Thurlbeck and assistant editor Greg Miskiw, who had then worked directly for editor Andy Coulson.[66] This contradicted testimony to the Culture, Media and Sport Committee by News International executives and senior Met officials that there was no evidence of hacking by anyone other than Mulcaire and Goodman. Within five weeks of the article appearing,

- Ian Edmondson was suspended from the News of the World,[67]

- Andy Coulson resigned as Chief Press Secretary to David Cameron,[68][69]

- the Crown Prosecution Service began a review of evidence it had,[70]

- the Met renewed its investigation into phone hacking, something it had previously declined to do.[66]

January–June 2011: Admission of liability

Operation Weeting begins

The Metropolitan Police announced on 26 January 2011 that it would begin a new investigation into phone hacking, following the receipt of "significant new information" regarding the conduct of News of the World employees.[71] Operation Weeting would take place alongside the previously announced review of phone hacking evidence by the Crown Prosecution Service.[72] Between 45 and 60 officers began looking over the 11,000 pages of evidence seized from Mulcaire in August 2006.[73][74]

In June 2011, the issue of computer hacking was addressed with the launch of Operation Tuleta.

Having failed thus far to put the phone hacking issue to rest, News International's law firm, Hickman & Rose, hired former Director of Public Prosecutions Ken Macdonald to review the emails that News International executives had used as the basis of their claim that no one at the News of the World but Clive Goodman had been involved in phone hacking. Macdonald immediately concluded, regardless of whether others had been involved, that there was clear evidence of criminal activity, including payments to serving police officers. Macdonald arranged for this evidence to be turned over to the Met, which led to their opening in July 2011 of Operation Elveden, an investigation focused on bribery and corruption within the Met's ranks.

The first arrests as part of Operation Weeting were made on 5 April 2011. Ian Edmondson and the News of the World's chief reporter Neville Thurlbeck were arrested on suspicion of unlawfully intercepting voicemail messages.[75][76] Both men had denied participating in illegal activities. The paper's assistant news editor, James Weatherup, was taken into custody for questioning by the Metropolitan Police on 14 April 2011.[77][78][79][80] He had also dealt with some major fiscal issues, "managing huge budgets" and "crisis management" at the newspaper.[81]

The Guardian, referring to the Information Commissioner's report of 2006, queried why the Metropolitan Police chose to exclude a large quantity of material relating to Jonathan Rees from the scope of its Operation Weeting inquiry.[82] The News of the World was said to have made extensive use of Rees' investigative services, including phone hacking, paying him up to £150,000 a year.[83] On the basis of evidence obtained during Operation Nigeria, Rees was found guilty in December 2000 of attempting to pervert the course of justice and received a seven-year prison sentence.[84] After he was released from prison the News of the World, under the editorship of Andy Coulson, began commissioning Rees' services again.[83]

The Guardian journalist Nick Davies described commissions from the News of the World as the "golden source" of income for Rees' "empire of corruption", which involved a network of contacts with corrupt police officers and a pattern of illegal behaviour extending far beyond phone hacking.[85] Despite detailed evidence, the Metropolitan Police failed to pursue effective in-depth investigations into Rees' corrupt relationship with the News of the World over more than a decade.[83]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=News_International_phone_hacking_scandal

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk