A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Orchid Temporal range: Late Cretaceous – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Orchidaceae Juss.[1] |

| Type genus | |

| Orchis | |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

| |

| Distribution range of family Orchidaceae | |

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (/ˌɔːrkɪˈdeɪsi.iː, -si.aɪ/),[2] a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant. Orchids are cosmopolitan plants that are found in almost every habitat on Earth except glaciers. The world's richest diversity of orchid genera and species is found in the tropics.

Orchidaceae is one of the two largest families of flowering plants, along with the Asteraceae. It contains about 28,000 currently accepted species distributed across 763 genera.[3][4]

The Orchidaceae family encompasses about 6–11% of all species of seed plants.[5] The largest genera are Bulbophyllum (2,000 species), Epidendrum (1,500 species), Dendrobium (1,400 species) and Pleurothallis (1,000 species). It also includes Vanilla (the genus of the vanilla plant), the type genus Orchis, and many commonly cultivated plants such as Phalaenopsis and Cattleya. Moreover, since the introduction of tropical species into cultivation in the 19th century, horticulturists have produced more than 100,000 hybrids and cultivars.

Description

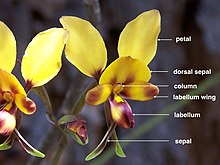

Orchids are easily distinguished from other plants, as they share some very evident derived characteristics or synapomorphies. Among these are: bilateral symmetry of the flower (zygomorphism), many resupinate flowers, a nearly always highly modified petal (labellum), fused stamens and carpels, and extremely small seeds.

Stem and roots

All orchids are perennial herbs that lack any permanent woody structure. They can grow according to two patterns:

- Monopodial: The stem grows from a single bud, leaves are added from the apex each year, and the stem grows longer accordingly. The stem of orchids with a monopodial growth can reach several metres in length, as in Vanda and Vanilla.

- Sympodial: Sympodial orchids have a front (the newest growth) and a back (the oldest growth).[6] The plant produces a series of adjacent shoots, which grow to a certain size, bloom and then stop growing and are replaced. Sympodial orchids grow horizontally, rather than vertically, following the surface of their support. The growth continues by development of new leads, with their own leaves and roots, sprouting from or next to those of the previous year, as in Cattleya. While a new lead is developing, the rhizome may start its growth again from a so-called 'eye', an undeveloped bud, thereby branching. Sympodial orchids may have visible pseudobulbs joined by a rhizome, which creeps along the top or just beneath the soil.

Terrestrial orchids may be rhizomatous or form corms or tubers. The root caps of terrestrial orchids are smooth and white.

Some sympodial terrestrial orchids, such as Orchis and Ophrys, have two subterranean tuberous roots. One is used as a food reserve for wintry periods, and provides for the development of the other one, from which visible growth develops.

In warm and constantly humid climates, many terrestrial orchids do not need pseudobulbs.

Epiphytic orchids, those that grow upon a support, have modified aerial roots that can sometimes be a few meters long. In the older parts of the roots, a modified spongy epidermis, called a velamen, has the function of absorbing humidity. It is made of dead cells and can have a silvery-grey, white or brown appearance. In some orchids, the velamen includes spongy and fibrous bodies near the passage cells, called tilosomes.

The cells of the root epidermis grow at a right angle to the axis of the root to allow them to get a firm grasp on their support. Nutrients for epiphytic orchids mainly come from mineral dust, organic detritus, animal droppings and other substances collecting among on their supporting surfaces.

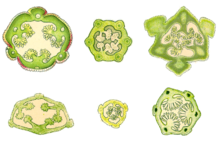

The base of the stem of sympodial epiphytes, or in some species essentially the entire stem, may be thickened to form a pseudobulb that contains nutrients and water for drier periods.

The pseudobulb typically has a smooth surface with lengthwise grooves, and can have different shapes, often conical or oblong. Its size is very variable; in some small species of Bulbophyllum, it is no longer than two millimeters, while in the largest orchid in the world, Grammatophyllum speciosum (giant orchid), it can reach three meters. Some Dendrobium species have long, canelike pseudobulbs with short, rounded leaves over the whole length; some other orchids have hidden or extremely small pseudobulbs, completely included inside the leaves.

With ageing the pseudobulb sheds its leaves and becomes dormant. At this stage it is often called a backbulb. Backbulbs still hold nutrition for the plant, but then a pseudobulb usually takes over, exploiting the last reserves accumulated in the backbulb, which eventually dies off, too. A pseudobulb typically lives for about five years. Orchids without noticeable pseudobulbs are also said to have growths, an individual component of a sympodial plant.

Leaves

Like most monocots, orchids generally have simple leaves with parallel veins, although some Vanilloideae have reticulate venation. Leaves may be ovate, lanceolate, or orbiculate, and very variable in size on the individual plant. Their characteristics are often diagnostic. They are normally alternate on the stem, often folded lengthwise along the centre ("plicate"), and have no stipules. Orchid leaves often have siliceous bodies called stegmata in the vascular bundle sheaths (not present in the Orchidoideae) and are fibrous.

The structure of the leaves corresponds to the specific habitat of the plant. Species that typically bask in sunlight, or grow on sites which can be occasionally very dry, have thick, leathery leaves and the laminae are covered by a waxy cuticle to retain their necessary water supply. Shade-loving species, on the other hand, have long, thin leaves.

The leaves of most orchids are perennial, that is, they live for several years, while others, especially those with plicate leaves as in Catasetum, shed them annually and develop new leaves together with new pseudobulbs.

The leaves of some orchids are considered ornamental. The leaves of Macodes sanderiana, a semiterrestrial or rock-hugging ("lithophyte") orchid, show a sparkling silver and gold veining on a light green background. The cordate leaves of Psychopsiella limminghei are light brownish-green with maroon-puce markings, created by flower pigments. The attractive mottle of the leaves of lady's slippers from tropical and subtropical Asia (Paphiopedilum), is caused by uneven distribution of chlorophyll. Also, Phalaenopsis schilleriana is a pastel pink orchid with leaves spotted dark green and light green. The jewel orchid (Ludisia discolor) is grown more for its colorful leaves than its white flowers.

Some orchids, such as Dendrophylax lindenii (ghost orchid), Aphyllorchis and Taeniophyllum depend on their green roots for photosynthesis and lack normally developed leaves, as do all of the heterotrophic species.

Orchids of the genus Corallorhiza (coralroot orchids) lack leaves altogether and instead wrap their roots around the roots of mature trees and use specialized fungi to harvest sugars.[7]

Flowers

Orchid flowers have three sepals, three petals and a three-chambered ovary. The three sepals and two of the petals are often similar to each other but one petal is usually highly modified, forming a "lip" or labellum. In most orchid genera, as the flower develops, it undergoes a twisting through 180°, called resupination, so that the labellum lies below the column. The labellum functions to attract insects, and in resupinate flowers, also acts as a landing stage, or sometimes a trap.[8][9][10][11]

The reproductive parts of an orchid flower are unique in that the stamens and style are joined to form a single structure, the column.[10][11][12] Instead of being released singly, thousands of pollen grains are contained in one or two bundles called pollinia that are attached to a sticky disc near the top of the column. Just below the pollinia is a second, larger sticky plate called the stigma.[8][9][10][11]

Reproduction

Pollination

The complex mechanisms that orchids have evolved to achieve cross-pollination were investigated by Charles Darwin and described in Fertilisation of Orchids (1862). Orchids have developed highly specialized pollination systems, thus the chances of being pollinated are often scarce, so orchid flowers usually remain receptive for very long periods, rendering unpollinated flowers long-lasting in cultivation. Most orchids deliver pollen in a single mass. Each time pollination succeeds, thousands of ovules can be fertilized.

Pollinators are often visually attracted by the shape and colours of the labellum. However, some Bulbophyllum species attract male fruit flies (Bactrocera and Zeugodacus spp.) solely via a floral chemical which simultaneously acts as a floral reward (e.g. methyl eugenol, raspberry ketone, or zingerone) to perform pollination.[13] The flowers may produce attractive odours. Although absent in most species, nectar may be produced in a spur of the labellum (8 in the illustration above), or on the point of the sepals, or in the septa of the ovary, the most typical position amongst the Asparagales.

In orchids that produce pollinia, pollination happens as some variant of the following sequence: when the pollinator enters into the flower, it touches a viscidium, which promptly sticks to its body, generally on the head or abdomen. While leaving the flower, it pulls the pollinium out of the anther, as it is connected to the viscidium by the caudicle or stipe. The caudicle then bends and the pollinium is moved forwards and downwards. When the pollinator enters another flower of the same species, the pollinium has taken such position that it will stick to the stigma of the second flower, just below the rostellum, pollinating it. In horticulture, artificial orchid pollination is achieved by removing the pollinia with a small instrument such as a toothpick from the pollen parent and transferring them to the seed parent.

Some orchids mainly or totally rely on self-pollination, especially in colder regions where pollinators are particularly rare. The caudicles may dry up if the flower has not been visited by any pollinator, and the pollinia then fall directly on the stigma. Otherwise, the anther may rotate and then enter the stigma cavity of the flower (as in Holcoglossum amesianum).

The slipper orchid Paphiopedilum parishii reproduces by self-fertilization. This occurs when the anther changes from a solid to a liquid state and directly contacts the stigma surface without the aid of any pollinating agent or floral assembly.[14]

The labellum of the Cypripedioideae is poke bonnet-shaped, and has the function of trapping visiting insects. The only exit leads to the anthers that deposit pollen on the visitor.

In some extremely specialized orchids, such as the Eurasian genus Ophrys, the labellum is adapted to have a colour, shape, and odour which attracts male insects via mimicry of a receptive female. Pollination happens as the insect attempts to mate with flowers.

Many neotropical orchids are pollinated by male orchid bees, which visit the flowers to gather volatile chemicals they require to synthesize pheromonal attractants. Males of such species as Euglossa imperialis or Eulaema meriana have been observed to leave their territories periodically to forage for aromatic compounds, such as cineole, to synthesize pheromone for attracting and mating with females.[15][16] Each type of orchid places the pollinia on a different body part of a different species of bee, so as to enforce proper cross-pollination.

A rare achlorophyllous saprophytic orchid growing entirely underground in Australia, Rhizanthella slateri, is never exposed to light, and depends on ants and other terrestrial insects to pollinate it.

Catasetum, a genus discussed briefly by Darwin, actually launches its viscid pollinia with explosive force when an insect touches a seta, knocking the pollinator off the flower.

After pollination, the sepals and petals fade and wilt, but they usually remain attached to the ovary.

In 2011, Bulbophyllum nocturnum was discovered to flower nocturnally.[17]

Asexual reproduction

Some species, such as in the genera Phalaenopsis, Dendrobium, and Vanda, produce offshoots or plantlets formed from one of the nodes along the stem, through the accumulation of growth hormones at that point. These shoots are known as keiki.[18]

Epipogium aphyllum exhibits a dual reproductive strategy, engaging in both sexual and asexual seed production. The likelihood of apomixis playing a substantial role in successful reproduction appears minimal. Within certain petite orchid species groups, there is a noteworthy preparation of female gametes for fertilization preceding the act of pollination. [19]

Fruits and seeds

The ovary typically develops into a capsule that is dehiscent by three or six longitudinal slits, while remaining closed at both ends.

The seeds are generally almost microscopic and very numerous, in some species over a million per capsule. After ripening, they blow off like dust particles or spores. Most orchid species lack endosperm in their seed and must enter symbiotic relationships with various mycorrhizal basidiomyceteous fungi that provide them the necessary nutrients to germinate, so almost all orchid species are mycoheterotrophic during germination and reliant upon fungi to complete their lifecycles. Only a handful of orchid species have seed that can germinate without mycorrhiza, namely the species within the genus Disa with hydrochorous seeds.[20][21]

As the chance for a seed to meet a suitable fungus is very small, only a minute fraction of all the seeds released grow into adult plants. In cultivation, germination typically takes weeks.

Horticultural techniques have been devised for germinating orchid seeds on an artificial nutrient medium, eliminating the requirement of the fungus for germination and greatly aiding the propagation of ornamental orchids. The usual medium for the sowing of orchids in artificial conditions is agar gel combined with a carbohydrate energy source. The carbohydrate source can be combinations of discrete sugars or can be derived from other sources such as banana, pineapple, peach, or even tomato puree or coconut water. After the preparation of the agar medium, it is poured into test tubes or jars which are then autoclaved (or cooked in a pressure cooker) to sterilize the medium. After cooking, the medium begins to gel as it cools.

Taxonomy

The taxonomy of this family is in constant flux, as new studies continue to clarify the relationships between species and groups of species, allowing more taxa at several ranks to be recognized. The Orchidaceae is currently placed in the order Asparagales by the APG III system of 2009.[1]

Five subfamilies are recognised. The cladogram below was made according to the APG system of 1998. It represents the view that most botanists had held up to that time. It was supported by morphological studies, but never received strong support in molecular phylogenetic studies.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2015, a phylogenetic study[22] showed strong statistical support for the following topology of the orchid tree, using 9 kb of plastid and nuclear DNA from 7 genes, a topology that was confirmed by a phylogenomic study in the same year.[23]