A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Psychology is the study of mind and behavior.[1] Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both conscious and unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feelings, and motives. Psychology is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between the natural and social sciences. Biological psychologists seek an understanding of the emergent properties of brains, linking the discipline to neuroscience. As social scientists, psychologists aim to understand the behavior of individuals and groups.[2][3]

A professional practitioner or researcher involved in the discipline is called a psychologist. Some psychologists can also be classified as behavioral or cognitive scientists. Some psychologists attempt to understand the role of mental functions in individual and social behavior. Others explore the physiological and neurobiological processes that underlie cognitive functions and behaviors.

Psychologists are involved in research on perception, cognition, attention, emotion, intelligence, subjective experiences, motivation, brain functioning, and personality. Psychologists' interests extend to interpersonal relationships, psychological resilience, family resilience, and other areas within social psychology. They also consider the unconscious mind.[4] Research psychologists employ empirical methods to infer causal and correlational relationships between psychosocial variables. Some, but not all, clinical and counseling psychologists rely on symbolic interpretation.

While psychological knowledge is often applied to the assessment and treatment of mental health problems, it is also directed towards understanding and solving problems in several spheres of human activity. By many accounts, psychology ultimately aims to benefit society.[5][6][7] Many psychologists are involved in some kind of therapeutic role, practicing psychotherapy in clinical, counseling, or school settings. Other psychologists conduct scientific research on a wide range of topics related to mental processes and behavior. Typically the latter group of psychologists work in academic settings (e.g., universities, medical schools, or hospitals). Another group of psychologists is employed in industrial and organizational settings.[8] Yet others are involved in work on human development, aging, sports, health, forensic science, education, and the media.

Etymology and definitions

The word psychology derives from the Greek word psyche, for spirit or soul. The latter part of the word psychology derives from -λογία -logia, which means "study" or "research".[9] The word psychology was first used in the Renaissance.[10] In its Latin form psychiologia, it was first employed by the Croatian humanist and Latinist Marko Marulić in his book Psichiologia de ratione animae humanae (Psychology, on the Nature of the Human Soul) in the decade 1510-1520[10][11] The earliest known reference to the word psychology in English was by Steven Blankaart in 1694 in The Physical Dictionary. The dictionary refers to "Anatomy, which treats the Body, and Psychology, which treats of the Soul."[12]

Ψ (psi), the first letter of the Greek word psyche from which the term psychology is derived, is commonly associated with the field of psychology.

In 1890, William James defined psychology as "the science of mental life, both of its phenomena and their conditions."[13] This definition enjoyed widespread currency for decades. However, this meaning was contested, notably by radical behaviorists such as John B. Watson, who in 1913 asserted that the discipline is a natural science, the theoretical goal of which "is the prediction and control of behavior."[14] Since James defined "psychology", the term more strongly implicates scientific experimentation.[15][14] Folk psychology is the understanding of the mental states and behaviors of people held by ordinary people, as contrasted with psychology professionals' understanding.[16]

History

The ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, China, India, and Persia all engaged in the philosophical study of psychology. In Ancient Egypt the Ebers Papyrus mentioned depression and thought disorders.[17] Historians note that Greek philosophers, including Thales, Plato, and Aristotle (especially in his De Anima treatise),[18] addressed the workings of the mind.[19] As early as the 4th century BC, the Greek physician Hippocrates theorized that mental disorders had physical rather than supernatural causes.[20] In 387 BCE, Plato suggested that the brain is where mental processes take place, and in 335 BCE Aristotle suggested that it was the heart.[21]

In China, psychological understanding grew from the philosophical works of Laozi and Confucius, and later from the doctrines of Buddhism.[22] This body of knowledge involves insights drawn from introspection and observation, as well as techniques for focused thinking and acting. It frames the universe in term of a division of physical reality and mental reality as well as the interaction between the physical and the mental.[citation needed] Chinese philosophy also emphasized purifying the mind in order to increase virtue and power. An ancient text known as The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine identifies the brain as the nexus of wisdom and sensation, includes theories of personality based on yin–yang balance, and analyzes mental disorder in terms of physiological and social disequilibria. Chinese scholarship that focused on the brain advanced during the Qing dynasty with the work of Western-educated Fang Yizhi (1611–1671), Liu Zhi (1660–1730), and Wang Qingren (1768–1831). Wang Qingren emphasized the importance of the brain as the center of the nervous system, linked mental disorder with brain diseases, investigated the causes of dreams and insomnia, and advanced a theory of hemispheric lateralization in brain function.[23]

Influenced by Hinduism, Indian philosophy explored distinctions in types of awareness. A central idea of the Upanishads and other Vedic texts that formed the foundations of Hinduism was the distinction between a person's transient mundane self and their eternal, unchanging soul. Divergent Hindu doctrines and Buddhism have challenged this hierarchy of selves, but have all emphasized the importance of reaching higher awareness. Yoga encompasses a range of techniques used in pursuit of this goal. Theosophy, a religion established by Russian-American philosopher Helena Blavatsky, drew inspiration from these doctrines during her time in British India.[24][25]

Psychology was of interest to Enlightenment thinkers in Europe. In Germany, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) applied his principles of calculus to the mind, arguing that mental activity took place on an indivisible continuum. He suggested that the difference between conscious and unconscious awareness is only a matter of degree. Christian Wolff identified psychology as its own science, writing Psychologia Empirica in 1732 and Psychologia Rationalis in 1734. Immanuel Kant advanced the idea of anthropology as a discipline, with psychology an important subdivision. Kant, however, explicitly rejected the idea of an experimental psychology, writing that "the empirical doctrine of the soul can also never approach chemistry even as a systematic art of analysis or experimental doctrine, for in it the manifold of inner observation can be separated only by mere division in thought, and cannot then be held separate and recombined at will (but still less does another thinking subject suffer himself to be experimented upon to suit our purpose), and even observation by itself already changes and displaces the state of the observed object."

In 1783, Ferdinand Ueberwasser (1752–1812) designated himself Professor of Empirical Psychology and Logic and gave lectures on scientific psychology, though these developments were soon overshadowed by the Napoleonic Wars.[26] At the end of the Napoleonic era, Prussian authorities discontinued the Old University of Münster.[26] Having consulted philosophers Hegel and Herbart, however, in 1825 the Prussian state established psychology as a mandatory discipline in its rapidly expanding and highly influential educational system. However, this discipline did not yet embrace experimentation.[27] In England, early psychology involved phrenology and the response to social problems including alcoholism, violence, and the country's crowded "lunatic" asylums.[28]

Beginning of experimental psychology

Philosopher John Stuart Mill believed that the human mind was open to scientific investigation, even if the science is in some ways inexact.[29] Mill proposed a "mental chemistry" in which elementary thoughts could combine into ideas of greater complexity.[29] Gustav Fechner began conducting psychophysics research in Leipzig in the 1830s. He articulated the principle that human perception of a stimulus varies logarithmically according to its intensity.[30]: 61 The principle became known as the Weber–Fechner law. Fechner's 1860 Elements of Psychophysics challenged Kant's negative view with regard to conducting quantitative research on the mind.[31][27] Fechner's achievement was to show that "mental processes could not only be given numerical magnitudes, but also that these could be measured by experimental methods."[27] In Heidelberg, Hermann von Helmholtz conducted parallel research on sensory perception, and trained physiologist Wilhelm Wundt. Wundt, in turn, came to Leipzig University, where he established the psychological laboratory that brought experimental psychology to the world. Wundt focused on breaking down mental processes into the most basic components, motivated in part by an analogy to recent advances in chemistry, and its successful investigation of the elements and structure of materials.[32] Paul Flechsig and Emil Kraepelin soon created another influential laboratory at Leipzig, a psychology-related lab, that focused more on experimental psychiatry.[27]

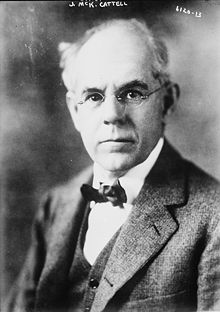

James McKeen Cattell, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University and the co-founder of Psychological Review, was the first professor of psychology in the United States.

The German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, a researcher at the University of Berlin, was a 19th-century contributor to the field. He pioneered the experimental study of memory and developed quantitative models of learning and forgetting.[33] In the early 20th century, Wolfgang Kohler, Max Wertheimer, and Kurt Koffka co-founded the school of Gestalt psychology of Fritz Perls. The approach of Gestalt psychology is based upon the idea that individuals experience things as unified wholes. Rather than reducing thoughts and behavior into smaller component elements, as in structuralism, the Gestaltists maintained that whole of experience is important, and differs from the sum of its parts.

Psychologists in Germany, Denmark, Austria, England, and the United States soon followed Wundt in setting up laboratories.[34] G. Stanley Hall, an American who studied with Wundt, founded a psychology lab that became internationally influential. The lab was located at Johns Hopkins University. Hall, in turn, trained Yujiro Motora, who brought experimental psychology, emphasizing psychophysics, to the Imperial University of Tokyo.[35] Wundt's assistant, Hugo Münsterberg, taught psychology at Harvard to students such as Narendra Nath Sen Gupta—who, in 1905, founded a psychology department and laboratory at the University of Calcutta.[24] Wundt's students Walter Dill Scott, Lightner Witmer, and James McKeen Cattell worked on developing tests of mental ability. Cattell, who also studied with eugenicist Francis Galton, went on to found the Psychological Corporation. Witmer focused on the mental testing of children; Scott, on employee selection.[30]: 60

Another student of Wundt, the Englishman Edward Titchener, created the psychology program at Cornell University and advanced "structuralist" psychology. The idea behind structuralism was to analyze and classify different aspects of the mind, primarily through the method of introspection.[36] William James, John Dewey, and Harvey Carr advanced the idea of functionalism, an expansive approach to psychology that underlined the Darwinian idea of a behavior's usefulness to the individual. In 1890, James wrote an influential book, The Principles of Psychology, which expanded on the structuralism. He memorably described "stream of consciousness." James's ideas interested many American students in the emerging discipline.[36][13][30]: 178–82 Dewey integrated psychology with societal concerns, most notably by promoting progressive education, inculcating moral values in children, and assimilating immigrants.[30]: 196–200

A different strain of experimentalism, with a greater connection to physiology, emerged in South America, under the leadership of Horacio G. Piñero at the University of Buenos Aires.[37] In Russia, too, researchers placed greater emphasis on the biological basis for psychology, beginning with Ivan Sechenov's 1873 essay, "Who Is to Develop Psychology and How?" Sechenov advanced the idea of brain reflexes and aggressively promoted a deterministic view of human behavior.[38] The Russian-Soviet physiologist Ivan Pavlov discovered in dogs a learning process that was later termed "classical conditioning" and applied the process to human beings.[39]

Consolidation and funding

One of the earliest psychology societies was La Société de Psychologie Physiologique in France, which lasted from 1885 to 1893. The first meeting of the International Congress of Psychology sponsored by the International Union of Psychological Science took place in Paris, in August 1889, amidst the World's Fair celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution. William James was one of three Americans among the 400 attendees. The American Psychological Association (APA) was founded soon after, in 1892. The International Congress continued to be held at different locations in Europe and with wide international participation. The Sixth Congress, held in Geneva in 1909, included presentations in Russian, Chinese, and Japanese, as well as Esperanto. After a hiatus for World War I, the Seventh Congress met in Oxford, with substantially greater participation from the war-victorious Anglo-Americans. In 1929, the Congress took place at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, attended by hundreds of members of the APA.[34] Tokyo Imperial University led the way in bringing new psychology to the East. New ideas about psychology diffused from Japan into China.[23][35]

American psychology gained status upon the U.S.'s entry into World War I. A standing committee headed by Robert Yerkes administered mental tests ("Army Alpha" and "Army Beta") to almost 1.8 million soldiers.[40] Subsequently, the Rockefeller family, via the Social Science Research Council, began to provide funding for behavioral research.[41][42] Rockefeller charities funded the National Committee on Mental Hygiene, which disseminated the concept of mental illness and lobbied for applying ideas from psychology to child rearing.[40][43] Through the Bureau of Social Hygiene and later funding of Alfred Kinsey, Rockefeller foundations helped establish research on sexuality in the U.S.[44] Under the influence of the Carnegie-funded Eugenics Record Office, the Draper-funded Pioneer Fund, and other institutions, the eugenics movement also influenced American psychology. In the 1910s and 1920s, eugenics became a standard topic in psychology classes.[45] In contrast to the US, in the UK psychology was met with antagonism by the scientific and medical establishments, and up until 1939, there were only six psychology chairs in universities in England.[46]

During World War II and the Cold War, the U.S. military and intelligence agencies established themselves as leading funders of psychology by way of the armed forces and in the new Office of Strategic Services intelligence agency. University of Michigan psychologist Dorwin Cartwright reported that university researchers began large-scale propaganda research in 1939–1941. He observed that "the last few months of the war saw a social psychologist become chiefly responsible for determining the week-by-week-propaganda policy for the United States Government." Cartwright also wrote that psychologists had significant roles in managing the domestic economy.[47] The Army rolled out its new General Classification Test to assess the ability of millions of soldiers. The Army also engaged in large-scale psychological research of troop morale and mental health.[48] In the 1950s, the Rockefeller Foundation and Ford Foundation collaborated with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to fund research on psychological warfare.[49] In 1965, public controversy called attention to the Army's Project Camelot, the "Manhattan Project" of social science, an effort which enlisted psychologists and anthropologists to analyze the plans and policies of foreign countries for strategic purposes.[50][51]

In Germany after World War I, psychology held institutional power through the military, which was subsequently expanded along with the rest of the military during Nazi Germany.[27] Under the direction of Hermann Göring's cousin Matthias Göring, the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was renamed the Göring Institute. Freudian psychoanalysts were expelled and persecuted under the anti-Jewish policies of the Nazi Party, and all psychologists had to distance themselves from Freud and Adler, founders of psychoanalysis who were also Jewish.[52] The Göring Institute was well-financed throughout the war with a mandate to create a "New German Psychotherapy." This psychotherapy aimed to align suitable Germans with the overall goals of the Reich. As described by one physician, "Despite the importance of analysis, spiritual guidance and the active cooperation of the patient represent the best way to overcome individual mental problems and to subordinate them to the requirements of the Volk and the Gemeinschaft." Psychologists were to provide Seelenführung , the leadership of the mind, to integrate people into the new vision of a German community.[53] Harald Schultz-Hencke melded psychology with the Nazi theory of biology and racial origins, criticizing psychoanalysis as a study of the weak and deformed.[54] Johannes Heinrich Schultz, a German psychologist recognized for developing the technique of autogenic training, prominently advocated sterilization and euthanasia of men considered genetically undesirable, and devised techniques for facilitating this process.[55]

After the war, new institutions were created although some psychologists, because of their Nazi affiliation, were discredited. Alexander Mitscherlich founded a prominent applied psychoanalysis journal called Psyche. With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, Mitscherlich established the first clinical psychosomatic medicine division at Heidelberg University. In 1970, psychology was integrated into the required studies of medical students.[56]

After the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks promoted psychology as a way to engineer the "New Man" of socialism. Consequently, university psychology departments trained large numbers of students in psychology. At the completion of training, positions were made available for those students at schools, workplaces, cultural institutions, and in the military. The Russian state emphasized pedology and the study of child development. Lev Vygotsky became prominent in the field of child development.[38] The Bolsheviks also promoted free love and embraced the doctrine of psychoanalysis as an antidote to sexual repression.[57]: 84–6 [58] Although pedology and intelligence testing fell out of favor in 1936, psychology maintained its privileged position as an instrument of the Soviet Union.[38] Stalinist purges took a heavy toll and instilled a climate of fear in the profession, as elsewhere in Soviet society.[57]: 22 Following World War II, Jewish psychologists past and present, including Lev Vygotsky, A.R. Luria, and Aron Zalkind, were denounced; Ivan Pavlov (posthumously) and Stalin himself were celebrated as heroes of Soviet psychology.[57]: 25–6, 48–9 Soviet academics experienced a degree of liberalization during the Khrushchev Thaw. The topics of cybernetics, linguistics, and genetics became acceptable again. The new field of engineering psychology emerged. The field involved the study of the mental aspects of complex jobs (such as pilot and cosmonaut). Interdisciplinary studies became popular and scholars such as Georgy Shchedrovitsky developed systems theory approaches to human behavior.[57]: 27–33

Twentieth-century Chinese psychology originally modeled itself on U.S. psychology, with translations from American authors like William James, the establishment of university psychology departments and journals, and the establishment of groups including the Chinese Association of Psychological Testing (1930) and the Chinese Psychological Society (1937). Chinese psychologists were encouraged to focus on education and language learning. Chinese psychologists were drawn to the idea that education would enable modernization. John Dewey, who lectured to Chinese audiences between 1919 and 1921, had a significant influence on psychology in China. Chancellor T'sai Yuan-p'ei introduced him at Peking University as a greater thinker than Confucius. Kuo Zing-yang who received a PhD at the University of California, Berkeley, became President of Zhejiang University and popularized behaviorism.[59]: 5–9 After the Chinese Communist Party gained control of the country, the Stalinist Soviet Union became the major influence, with Marxism–Leninism the leading social doctrine and Pavlovian conditioning the approved means of behavior change. Chinese psychologists elaborated on Lenin's model of a "reflective" consciousness, envisioning an "active consciousness" (pinyin: tzu-chueh neng-tung-li) able to transcend material conditions through hard work and ideological struggle. They developed a concept of "recognition" (pinyin: jen-shih) which referred to the interface between individual perceptions and the socially accepted worldview; failure to correspond with party doctrine was "incorrect recognition."[59]: 9–17 Psychology education was centralized under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, supervised by the State Council. In 1951, the academy created a Psychology Research Office, which in 1956 became the Institute of Psychology. Because most leading psychologists were educated in the United States, the first concern of the academy was the re-education of these psychologists in the Soviet doctrines. Child psychology and pedagogy for the purpose of a nationally cohesive education remained a central goal of the discipline.[59]: 18–24

Women in psychology

1900 - 1949

Women in the early 1900s started to make key findings within the world of psychology. In 1923, Anna Freud,[60] the daughter of Sigmund Freud, built on her father's work using different defense mechanisms (denial, repression, and suppression) to psychoanalyze children. She believed that once a child reached the latency period, child analysis could be used as a mode of therapy. She stated it is important focus on the child's environment, support their development, and prevent neurosis. She believed a child should be recognized as their own person with their own right and have each session catered to the child's specific needs. She encouraged drawing, moving freely, and expressing themselves in any way. This helped build a strong therapeutic alliance with child patients, which allows psychologists to observe their normal behavior. She continued her research on the impact of children after family separation, children with socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and all stages of child development from infancy to adolescence.

Functional periodicity, the belief women are mentally and physically impaired during menstruation, impacted women's rights because employers were less likely to hire them due to the belief they would be incapable of working for 1 week a month. Leta Stetter Hollingworth wanted to prove this hypothesis and Edward L. Thorndike's theory, that women have lesser psychological and physical traits than men and were simply mediocre, incorrect. Hollingworth worked to prove differences were not from male genetic superiority, but from culture. She also included the concept of women's impairment during menstruation in her research. She recorded both women and men performances on tasks (cognitive, perceptual, and motor) for three months. No evidence was found of decreased performance due to a woman's menstrual cycle.[61] She also challenged the belief intelligence is inherited and women here are intellectually inferior to men. She stated that women do not reach positions of power due to the societal norms and roles they are assigned. As she states in her article, "Variability as related to sex differences in achievement: A Critique",[62] the largest problem women have is the social order that was built due to the assumption women have less interests and abilities than men. To further prove her point, she completed another experiment with infants who have not been influenced by the environment of social norms, like the adult male getting more opportunities than women. She found no difference between infants besides size. After this research proved the original hypothesis wrong, Hollingworth was able to show there is no difference between the physiological and psychological traits of men and women, and women are not impaired during menstruation.[63]

The first half of the 1900s was filled with new theories and it was a turning point for women's recognition within the field of psychology. In addition to the contributions made by Leta Stetter Hollingworth and Anna Freud, Mary Whiton Calkins invented the paired associates technique of studying memory and developed self-psychology.[64] Karen Horney developed the concept of "womb envy" and neurotic needs.[65] Psychoanalyst Melanie Klein impacted developmental psychology with her research of play therapy.[66] These great discoveries and contributions were made during struggles of sexism, discrimination, and little recognition for their work.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=PsychologyText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk