A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

This article contains too many pictures for its overall length. (February 2024) |

São Paulo | |

|---|---|

| State of São Paulo Estado de São Paulo (Portuguese) Tetã São Paulo (Paulista) | |

| |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): "Éssepê",[1] "Estado Bandeirante" (Bandeirante State) "Locomotiva do Brasil" (Locomotive of Brazil) | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: Bandeirantes Anthem | |

Location of State of São Paulo in Brazil | |

| Coordinates: 23°32′S 46°38′W / 23.533°S 46.633°W | |

| Country | Brazil |

| Named for | Paul the Apostle |

| Capital | São Paulo |

| Government | |

| • Body | Legislative Assembly |

| • Governor | Tarcísio de Freitas (REP) |

| • Vice Governor | Felicio Ramuth (PSD) |

| • Senators | Alexandre Giordano (MDB) Marcos Pontes (PL) Mara Gabrilli (PSD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 248,219.5 km2 (95,838.1 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 12th |

| Population (2022)[4] | |

| • Total | 44,411,238 |

| • Estimate (2023) | 46,004,000[3] |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 183.46/km2 (475.2/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| Demonym | Paulista |

| GDP (nominal) | |

| • Year | 2021 |

| • Total | R$ 2.720 trillion (US$ 603.4 billion)[5][6] (1st) |

| • Per capita | R$ 61,223 US$ 11,357[5] (2nd) |

| Time zone | UTC-03:00 (BRT) |

| Postal Code | 01000-000 to 19990-000 |

| ISO 3166 code | BR-SP |

| License Plate Letter Sequence | BFA to GKI, QSN to QSZ, SAV |

| HDI | 2021 |

| Category | 0.780[7] – very high (2nd) |

| Website | SaoPaulo.sp.gov.br |

São Paulo (/ˌsaʊ ˈpaʊloʊ/; Portuguese pronunciation: [sɐ̃w ˈpawlu] ) is one of the 26 states of the Federative Republic of Brazil and is named after Saint Paul of Tarsus. It is located in the Southeast Region and is limited by the states of Minas Gerais to the north and northeast, Paraná to the south, Rio de Janeiro to the east and Mato Grosso do Sul to the west, in addition to the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast. It is divided into 645 municipalities and its total area is 248,219.481 square kilometres (95,838.077 square miles) km2, which is equivalent to 2.9% of Brazil's surface, being slightly larger than the United Kingdom. Its capital is the municipality of São Paulo.

With more than 44 million inhabitants in 2022,[8] São Paulo is the most populous Brazilian state (around 22% of the Brazilian population), the world's 28th-most-populous sub-national entity and the most populous sub-national entity in the Americas,[9] and the fourth-most-populous political entity of South America, surpassed only by the rest of the Brazilian federation, Colombia, and Argentina. The local population is one of the most diverse in the country and descended mostly from Italians, who began immigrating to the country in the late 19th century;[10] the Portuguese, who colonized Brazil and installed the first European settlements in the region; Indigenous peoples, many distinct ethnic groups; Africans, who were brought from Africa as slaves in the colonial era and migrants from other regions of the country. In addition, Arabs, Armenians, Chinese, Germans, Greeks, Japanese, Spanish and American Southerners[11] also are present in the ethnic composition of the local population.

The area that today corresponds to the state territory was already inhabited by Indigenous peoples from approximately 12,000 BC. In the early 16th century, the coast of the region was visited by Portuguese and Spanish explorers and navigators. In 1532 Martim Afonso de Sousa would establish the first Portuguese permanent settlement in the Americas[12]—the village of São Vicente, in the Baixada Santista. In the 17th century, the paulistas bandeirantes intensified the exploration of the colony's interior, which eventually expanded the territorial domain of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire in South America. In the 18th century, after the establishment of the province of São Paulo, the region began to gain political weight. After independence in 1822, São Paulo began to become a major agricultural producer (mainly coffee) in the newly constituted Empire of Brazil, which ultimately created a rich regional rural oligarchy, which would switch on the command of the Brazilian government with Minas Gerais's elites during the early republican period in the 1890s. Under the Vargas Era, the state was one of the first to initiate a process of industrialization and its population became one of the most urban of the federation.

São Paulo's economy is very strong and diversified, having the largest industrial, scientific and technological production in the country — being the largest national research and development hub and home to the best universities and institutes —, the world's largest production of orange juice, sugar and ethanol, and the highest GDP among all Brazilian states, being the only one to exceed the 1 trillion reais range. In 2020, São Paulo's economy accounted for around 31.2% of the total wealth produced in the country — which made the state known as the "locomotive of Brazil" — and this is reflected in its cities, many of which are among the richest and most developed in the country. São Paulo alone is wealthier than Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia combined, with a GDP of 2.7 trillion reais (603.4 billion dollars);[13] therefore, if it were a sovereign country, its nominal GDP would be the 21st largest in the world (2020 estimate). In addition to the great economy, São Paulo is the most sought after Brazilian tourist destination by national and international tourists due to its natural beauty, historical and cultural heritage —it has multiple sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List—, inland resorts, climate and great vocation for the service, business, entertainment, fashion sectors, culture, leisure, health, education, and many others. It has high social indices compared to those recorded in the rest of the country, such as the second-highest Human Development Index (HDI), the fourth GRDP per capita, the second-lowest infant mortality rate, the third-highest life expectancy, the lowest homicide rate, and the third-lowest rate of illiteracy among the federative units of Brazil.

History

Early period

The region of the current state of São Paulo was already inhabited by Amerindian peoples since at least approximately 10,000 BCE, as evidenced by studies carried out in ancient archaeological sites (such as the sites Caetetuba, Bastos, Boa Esperança II and Lagoa do Camargo) in different parts of the current territory of São Paulo. There are even records (e.g. - studies at the Rincão I archaeological site) that suggest that ancient human occupation was already present in São Paulo 17 thousand years ago, during the last glacial maximum.[14] There are also several archaeological sites (such as Caetetuba, Alice Boer and Rincão I) in the central portion of the state that share similar patterns of working rocks into stone points and plano-convex artifacts similar to each other, so that they are seen as members of the same ancient ancestral culture, linked to the Rioclarense lithic industry. These ancient human groups were hunter-gatherers, living as nomads and semi-nomads in the current territory of São Paulo, living directly from what they could obtain from the local land.[15]

In pre-European times, the area that is now São Paulo state was occupied by the Tupi people's nation, who subsisted through hunting and cultivation.[16] The first European to settle in the area was João Ramalho, a Portuguese sailor who may have been shipwrecked around 1510, ten years after the first Portuguese landfall in Brazil. He married the daughter of a local chieftain and became a settler. In 1532, the first colonial expedition, led by Martim Afonso de Sousa of Portugal, landed at São Vicente (near the present-day port at Santos). De Sousa added Ramalho's settlement to his colony.

Early European colonization of Brazil was very limited. Portugal was more interested in Africa and Asia. But with English and French raiding privateer ships just off the coast, the territory had to be protected. Unwilling to shoulder the naval defense burden himself, the Portuguese ruler, King Joao III, divided the coast into "captaincies", or swathes of land, 50 leagues apart. He distributed them among well-connected Portuguese, hoping that each would be self-reliant. The early port and sugar-cultivating settlement of São Vicente was one rare success connected to this policy. In 1548, João III brought Brazil under direct royal control.

Fearing Indian attack, he discouraged development of the territory's vast interior. Some whites headed nonetheless for Piratininga, a plateau near São Vicente, drawn by its navigable rivers and agricultural potential. Borda do Campo, the plateau settlement, became an official town (Santo André da Borda do Campo) in 1553. The history of São Paulo city proper begins with the founding of a Jesuit mission of the Roman Catholic order of clergy on 25 January 1554—the anniversary of Saint Paul's conversion. The station, which is at the heart of the current city, was named São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga (or just Pateo do Colégio). In 1560, the threat of Indian attack led many to flee from the exposed Santo André da Borda do Campo to the walled fortified Colegio. Two years later, the Colégio was besieged. Though the town survived, fighting took place sporadically for another three decades.

By 1600, the town had about 1,500 citizens and 150 households. Little was produced for export, save a number of agricultural goods. The isolation was to continue for many years, as the development of Brazil centered on the sugar plantations in the north-east.

The city's location, at the mouth of the Tietê-Paranapanema river system (which winds into the interior), made it an ideal base for another activity—enslaving expeditions. The economics were simple. Enslaved manpower for Brazil's northern sugar plantations were in short supply. Enslaved Africans were expensive, so demand for indigenous captives soared. The task was, nonetheless, hard, if not impossible, to achieve.

Expansion

Among those who attempted to enslave the native were explorers of the hinterland called "bandeirantes". From their base in São Paulo, they also combed the interior in search of natural riches. Silver, gold and diamonds were companion pursuits, as well as the exploration of unknown territories. Roman Catholic missionaries sometimes tagged along, as efforts at converting the natives aborigines (Indians) worked hand in hand with Portuguese colonialism.

Despite their atrocities, the wild and hardy bandeirantes are now equally remembered for penetrating Brazil's vast interior. Trading posts established by them became permanent settlements. Interior routes opened up. Though the bandeirantes had no loyalty to the Portuguese crown, they did claim land for the king. Thus, the borders of Brazil were pushed forward to the northwest and the Amazon region and west to the Andes Mountains.

French Emperor Napoleon's invasion of Portugal in 1807 prompted the British with their vast powerful Royal Navy to evacuate King João VI of Portugal, Portugal's prince regent, from the capital Lisbon, across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro and Brazil then became the first overseas colony to become the temporary headquarters of the Portuguese Empire. João VI rewarded his hosts with economic reforms that would prove crucial to São Paulo's rise. Brazil's ports—long closed to non-Portuguese ships—were opened up to international trade. Restrictions on domestic manufacturing were waived.

When Napoleon was defeated in 1815, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, João gave political shape to his territory, which soon became the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Portugal and Brazil, in other words, were ostensibly co-equals. Returning to Portugal six years later, João left his son, Pedro, to rule as regent and governor.

Empire of Brazil period

Pedro I of Brazil inherited his father's love of Brazil, resisting demands from Lisbon that Brazil should be ruled from Europe once again. Legend has it that in 1822 the regent was riding outside São Paulo when a messenger delivered a missive demanding his return to Europe, and Dom Pedro waved his sword and shouted "Independência ou morte!" (Independence or death).

João had whetted the appetite of Brazilians, who now sought a full break from the monarchy. The ever-restless Paulistas were at the vanguard of the independence movement. The small mother country of Portugal was in no position to resist—on 7 September 1822, Dom Pedro rubber-stamped Brazil's independence. He was crowned emperor shortly afterwards. The emperors ruled an independent Brazil until 1889. Over this time, the growth of liberalism in Europe had a parallel in Brazil. As the Brazilian provinces became more assertive, São Paulo was the scene of a minor (and unsuccessful) liberal revolution in 1842. When independence was declared, the city of São Paulo had just 25,000 people and 4,000 houses, but the next 60 years would see gradual growth. In 1828, the Law School, the pioneer of the city's intellectual tradition, opened. The first newspaper, O Farol Paulistano, appeared in 1827. Municipal developments such as botanical gardens, an opera house and a library, gave the city a cultural boost.

Regardless, São Paulo still faced many hurdles, especially transport. Mule-trains were the main method of transportation, and the road from the plateau down to the port of Santos was famously arduous. In the late 1860s São Paulo got its first railway line, developed by British engineers, to the Port of Santos. Other lines, such as a railway to Campinas, were soon built. This was good timing, because in the 1880s the coffee craze hit in earnest. Brazil, which had been growing it since the mid-18th century, could grow more. The Paraíba valley, which spans the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, had suitable soil and climate. São Paulo city, at the western end of the Paraíba valley, was well positioned to channel the coffee to the port of Santos.

Republican era

Meanwhile, the Brazilian monarchy had fallen in 1889. A feudalistic regime, the new republic had friends only among the sugar planters of the Northeast, whose dominance Paulistanos, among others, despised. In 1891, a new federal constitution, which delegated power to the states, was approved. The new coffee elite saw its chance. São Paulo ironed out a power-sharing understanding—known as the "café com leite" (coffee-and-milk) deal—with dairy-rich Minas Gerais, Brazil's other dominant state. Together, they held a virtual lock on federal power. Brazilian politics now became a favourite pastime of the once-rebellious Paulistanos, who sent several presidents to Rio de Janeiro—including Prudente de Morais, Brazil's first civilian president, who took office in 1894.

Plantation labor was needed—this time for coffee, not sugar. Slavery had been fading since the import of enslaved Africans was outlawed in 1850. São Paulo, thanks to such figures as Luiz Gama (a former slave), was a center of abolitionism. In 1888, Brazil abolished slavery (it was the last country in the Americas to do so) and the freed African-Brazilians who had been helping build the nation were then forced to beg for their jobs back, working for food and shelter only because of the failure of the system to integrate them as equal citizens with Euro-Brazilians. In an effort to "bleach the race", as the nation's leaders feared Brazil was becoming a "black country", Spanish, Portuguese and Italian nationals were given incentives to become farm workers in São Paulo. The state government was so eager to bring in European immigrants that it paid for their trips and provided varying levels of subsidy.

By 1893, foreigners made up over 55 percent of São Paulo's population. Fearing oversupply, the government applied the brakes briefly in 1899; then the boom resumed. From 1908, the Japanese arrived in great numbers, many destined for the plantations on fixed-term contracts. By 1920, São Paulo was Brazil's second-largest city; a half-century before, it had been just the tenth-largest. Immigration and migration of Paulistas from other towns as well as Nordestinos and citizens from other states, the coffee industry, and modernization through the manufacturing of textiles, car and airplane parts, as well as food and technological industries, construction, fashion, and services transformed the greater São Paulo area into a thriving megalopolis and one of the world's greatest multiethnic regions.

Early 20th century

Between 1901 and 1910, coffee made up 51 percent of Brazil's total exports, far overshadowing rubber, sugar and cotton. But reliance on coffee made Brazil (and São Paulo in particular) vulnerable to poor harvests and the whims of world markets. The development of plantations in the 1890s, and widespread reliance on credit, took place against fluctuating prices and supply levels, culminating in saturation of the international market around the start of the 20th century. The government's policies of "valorisation "—borrowing money to buy coffee and stockpiling it, in order to have a surplus during bad harvests, and meanwhile taxing coffee exports to pay off loans—seemed feasible in the short term (as did its manipulation of foreign-exchange rates to the advantage of coffee growers). But in the longer term, these actions contributed to oversupply and eventual collapse.

São Paulo's industrial development, from 1889 into the 1940s, was gradual and inward looking. Initially, industry was closely associated with agriculture: cotton plantations led to the growth of textile manufacturing. Coffee planters were among the early industrial investors.

The boom in immigration provided a market for goods, and sectors such as food processing grew. Traditional immigrant families such as the Matarazzo, Diniz, Mofarrej and Maluf became industrialists, entrepreneurs, and leading politicians.

Restrictions on imports forced by world wars and government policies of "import substitution" and trade tariffs, all contributed to industrial growth. By 1945, São Paulo had become the largest industrial center in South America. World War I sent ripples through Brazil. Inflation was rampant. Some 50,000 workers went on strike.

The growing of the urban population grew increasingly resentful of the coffee elite. Disaffected intellectuals expressed their views during a memorable "Week of Modern Art" in 1922. Two years later, a garrison of soldiers staged a revolt (eventually quashed by government troops).

The stand-off was also political: politics had been long monopolised by the Paulista Republican Party, but in 1926 a more left-leaning party rose in opposition. In 1928, the PRP amended São Paulo's state constitution to give it more control over the city. The turbulence was mirrored on Brazil's national scene. With the Great Depression, coffee prices plunged, as did real GDP. Americans, keen investors during the 1920s, backed away.

The opening of the first highway between São Paulo and Rio in 1928 was one of the few bright spots. Into the breach stepped Getúlio Vargas, a southerner veteran in state politics. In Brazil's 1930 presidential elections, he opposed Júlio Prestes, a favorite son of São Paulo. Vargas lost the election, but with backing from Minas Gerais state—São Paulo's former ally and neighbor to the north—he seized power regardless.

Constitutionalist Revolution

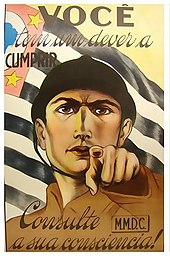

The Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932 or Paulista War is the name given to the uprising of the population of the Brazilian state of São Paulo against the federal government of Vargas. Its main goal was to press the provisional government headed by Getúlio Vargas to enact a new Constitution, since it had revoked the previous one, adopted in 1889. However, as the movement developed and resentment against President Vargas grew deeper, it came to advocate the overthrow of the Federal Government and the secession of São Paulo from the Brazilian federation. But, it is noted that the separatist scenario was used as guerrilla tactics by the Federal Government to turn the population of the rest of the country against the state of São Paulo, broadcasting the alleged separatist notion throughout the country. There is no evidence that the movement's commanders sought separatism.

The uprising started on 9 July 1932, after five protesting students were killed by government troops on 23 May 1932. On the wake of their deaths, a movement called MMDC (from the initials of the names of each of the four students killed, Martins, Miragaia, Dráusio and Camargo) started. A fifth victim, Alvarenga, was also shot that night, but died months later.

Revolutionary troops entrenched in the battlefield. In a few months, the state of São Paulo rebelled against the federal government. Counting on the solidarity of three other powerful states, (Rio Grande do Sul, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro), the politicians of São Paulo expected a quick war. However, that solidarity was never translated into actual support, and the São Paulo civil war was won by the Federation on 2 October 1932.

In spite of its military defeat, some of the movement's main demands were finally granted by Vargas afterwards: the appointment of a non-military state Governor, the election of a Constituent Assembly and, finally, the enactment of a new Constitution in 1934. However that Constitution was short lived, as in 1937, amidst growing extremism on the left and right wings of the political spectrum, Vargas closed the National Congress and enacted another Constitution, which established an authoritarian regime called Estado Novo.

Late 20th century

Vargas's rule was a study in political turbulence. Elected in 1934, he ruled by dictatorship (albeit a popular one, thanks to his health and social-welfare programmes) from 1937 to 1945—a period dubbed the "Estado Novo". Thrown out by a coup in 1945, he ran for office again in 1950, and was overwhelmingly elected. On the verge of being overthrown from office again, he committed suicide in 1954. Vargas's main legacy was the centralization of power.

The encouragement of industry and diversification of agriculture, not to mention the abolition of subsidies on coffee, finally did away with the dominance of the coffee oligarchies. His replacement, Juscelino Kubitschek, focused on heavy industry. Kubitschek built car factories, steel plants, hydro-power infrastructure and roads. Petrobras, Brazil's oil monolith, was set up in 1953. By 1958, São Paulo state controlled some 55 percent of Brazil's industrial production, up from 17 percent in 1907. Another of Kubitschek's pet projects was the creation of Brasília, which became Brazil's capital in 1960—the year Kubitschek stepped down. The University of São Paulo was founded in 1934; two years after São Paulo's failed uprising. It has established itself as the most prestigious higher learning institution in the country.

With a transitional government from military to civil and a new currency that made stagnant the economy during the mid- to late 1980s, unemployment and crime became rampant. São Paulo, by now the world's third-largest city after Mexico City and Tokyo, was hard-hit. Wealthy Brazilians retreated to suburban highly secured housing complexes such as Alphaville, and favelas, pockets of substandard living slums that lined the periphery, had a tremendous growth. For the first time in history, Brazil experienced large segments of its population immigrating to continents such as North America, Europe, Australia, and East Asia, particularly to Japan.[citation needed]

Geography

São Paulo is one of 27 states of Brazil, located southwest of the Southeast Region. The state area is 248,222.362 km2 (95,839.190 sq mi), most of the north of the Tropic of Capricorn, and the 12th unit of the Brazilian federation in area and the second in the Southeast region, behind only Minas Gerais. The state has a relatively high relief, having 85 percent of its surface between three hundred and nine hundred meters above sea level, 8 percent below three hundred meters and 7 percent over nine hundred meters.[17]

The distance between its north and south end points is 611 km (380 mi), and 923 km (574 mi) between the east–west extremes. The state time zone follows the Brasilia time, which is three hours behind Greenwich Mean Time. It is bordered by the states of Minas Gerais to the north and northeast, Paraná to the south, Rio de Janeiro to the east, Mato Grosso do Sul to the west, and the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast.[18]

The coastline consists of plains below 300 metres (980 ft), that border the Serra do Mar. Located in the Serra da Mantiqueira, Mine Stone, with 2,798 metres (9,180 ft) above sea level, is the highest point the state territory and the fifth in the country.[19]

São Paulo has its territory divided into 21 watersheds,[20] inserted in three river basin districts, the largest of which is the Paraná, which covers much of the state territory. Noteworthy is the Rio Grande, which born in Minas Gerais and join with Paranaiba to form the Parana River, which separates São Paulo from Mato Grosso do Sul.[21]

Two major rivers Paulistas tributaries of the left bank of the Paraná River are the Paranapanema, which is 930 km (580 mi) long and a natural divider between São Paulo and Paraná in most of its course,[22] and the Tiete River, which has a length of 1,136 km (706 mi) and runs through the state territory from southeast to northwest, from its source in Salesópolis, to its mouth in the city of Itapura.[23]

Climate

The state territory covers seven distinct climatic types, taking into account the temperature and rainfall. In the mountain areas of the state, there are subtropical climate (Cfa in Köppen climate classification), in areas of high altitude such as the Serra do Mar and the Serra da Mantiqueira, having humid, hot summers and average temperatures below 18 °C (64 °F) in the month cooler year; and oceanic (Cfb and Cwb) with regular and well distributed throughout the year and warmer summers rains.[24]

On the coast, the climate is super-humid tropical type, very similar to the prevailing equatorial climate in the Amazon (Af), with rainfall exceeding sixty monthly millimeters in every month of the year, without the existence of a dry season. The tropical climate of altitude (Cwa), predominant in the state territory, specifically in the center of the state, is characterized by a summer rainy season and a dry season in winter, with temperatures above 22 °C (72 °F) in the hottest month of the year. In other areas, there is tropical savanna climate (Aw) with rainfall less than 60 millimetres (2.4 in) in one or more months of the year and warmer, with average temperatures above 18 °C (64 °F) during the year. There are also small areas with characteristics of monsoons (Am).[24]

The occurrence of snow is very rare, but has been recorded in Campos do Jordão and there are also reports that the phenomenon has occurred in several parts of the south of the state, except for the Ribeira Valley.[25] The frosts are common, especially in higher areas with altitude of 800 metres (2,600 ft).[26]

Environment

São Paulo's territory is located, for the most part, in the Atlantic Forest biome, whose initial formation covered just over two thirds of São Paulo's territory and today is only spread out in several fragments, with 32.6% of the original remnants remaining today, most of it on the slopes of Serra do Mar. In the cerrado biome, typical of areas in the center-west of São Paulo, this number is even lower, at just 3%. On the coast there are small areas of dunes, with plant species adapted to heat and salinity, in addition to restingas and mangroves, the latter at the mouths of rivers. As it is located at the junction of the tropical and temperate zones of the planet, São Paulo has its fauna and flora made up of species from both tropical and subtropical regions, some of which are endemic.[27]

In 2020, only 22.9% of São Paulo's territory, or 5,670,532 hectares (ha), were covered by native vegetation, both untouched and in the regeneration stage.[27] That same year, São Paulo had 102 state conservation units and thirteen more federal ones, among areas of environmental protection and relevant ecological interest, ecological stations, national and state forests and parks, wildlife refuges, extractive and sustainable development reserves and also private natural heritage reserves (RPPN).[28]

Demographics

According to the IBGE estimates for 2022, there were 44,411,238 people residing in the state.[8] The population density was 177.4 inhabitants per square kilometre (459/sq mi).

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 837,354 | — |

| 1890 | 1,384,753 | +65.4% |

| 1900 | 2,282,279 | +64.8% |

| 1920 | 4,592,188 | +101.2% |

| 1940 | 7,180,316 | +56.4% |

| 1950 | 9,134,423 | +27.2% |

| 1960 | 12,974,699 | +42.0% |

| 1970 | 17,958,693 | +38.4% |

| 1980 | 25,375,199 | +41.3% |

| 1991 | 31,546,473 | +24.3% |

| 2000 | 36,969,476 | +17.2% |

| 2010 | 41,262,199 | +11.6% |

| 2022 | 44,411,238 | +7.6% |

| Source:[4] | ||

Racial groups of São Paulo (2022 census)[30]

The 2022 census revealed the following numbers: 25,661,895 White people (57.8%), 14,636,695 Brown (Multiracial) people (33%), 3,546,562 Black people (8%), 513,066 Asian people (1.2%), and 50,528 Amerindian people (0.1%).[31][32]

People of Italian descent predominate in many towns, including the capital city, where 48 percent of the population has at least one Italian ancestor. The Italians mostly came from Veneto and Campania.[33] There are 32 million descendants of Italians in Brazil, half of whom live in the state of São Paulo. Estimates point to 16 million descendants of Italians in São Paulo, around 35% of the state.

The Even population is 10.9% with 4.6 million inhabitants. Most of German, Swedish, Norwegian, Italian, Jewish, Scottish, Irish, Greek, and Polish descent.

Portuguese and Spanish descendants predominate in most towns. Most of the Portuguese immigrants and settlers came from the Entre-Douro-e-Minho Province in northern Portugal, the Spanish immigrants mostly came from Galicia and Andalusia.

People of African or Mixed background are relatively numerous. São Paulo is also home to the largest Asian population in Brazil, as well to the largest Japanese community outside Japan itself.[34]

There are many people of Levantine descent, mostly Syrian and Lebanese.[35] The majority of Brazilian Jews live in the state, especially in the capital city but there are also communities in Greater São Paulo, Santos, Guarujá, Campinas, Valinhos, Vinhedo, São José dos Campos, Ribeirão Preto, Sorocaba and Itu.

People of more than 70 different nationalities emigrated to Brazil in the past centuries, most of them through the Port of Santos in Santos, São Paulo. Although many of them spread to other areas of Brazil, São Paulo can be considered a true melting-pot. People of German, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Russian, Chinese, Korean, Polish, American, Bolivian, Greek and French background, as well as dozens of other immigrant groups, form sizable groups in the state.

Thousands of Southern refugees from the American Civil War, called Confederados, emigrated to Brazil, with many settling in São Paulo.[11][36]

A genetic study, from 2013, showed the overall composition of São Paulo to be: 61.9% European, 25.5% African and 11.6% Native American, respectively.[37]

According to an autosomal DNA genetic study (from 2006), the overall results were: 79 percent of the ancestry was European, 14 percent are of African origin, and 7 percent Native American.[38]

The city of São Paulo, the homonymous state capital, is ranked as the world's 12th largest city and its metropolitan area, with 20 million inhabitants,[9] is the 9th largest in the world and first in the Americas. Regions near the city of São Paulo are also metropolitan areas, such as Campinas, Santos, Sorocaba and São José dos Campos. The total population of these areas coupled with the state capital—the so-called "Expanded Metropolitan Complex of São Paulo"—exceeds 30 million inhabitants, i.e. approximately 75 percent of the population of São Paulo statewide, the first macro-metropolis in the southern hemisphere, joining 65 municipalities that together are home to 12 percent of the Brazilian population.

Metropolitan areas and urban agglomerations

The Metropolitan Region of São Paulo (RMSP), also known as Greater São Paulo, was established by federal complementary law nº 14 of 1973 and is made up of 39 municipalities in São Paulo, some of them in conurbations with a core city, São Paulo, forming a large continuous urban spot. It is the most populous metropolitan region in Brazil and one of the largest in the world, with an estimated population of approximately 21 million inhabitants in 2022, almost half of the state's population.[39] It is in the RMSP that the municipalities with the highest population density in the state of São Paulo are found: Taboão da Serra (13.416 inhabitants/km2), Diadema (12.795 inhabitants/km2), Osasco (11.445 inhab./km2), Carapicuíba (11.205 inhab./km2), São Caetano do Sul (10.805 inhab./km2), and São Paulo (7.527 inhab./km2).[40]

Largest urban concentrations in São Paulo (state)

(2022 census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)[41] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Pop. | Rank | Pop. | ||||||

São Paulo  Campinas |

1 | São Paulo | 20,673,280 | 11 | Franca | 397,769 |  Baixada Santista  São José dos Campos | ||

| 2 | Campinas | 2,093,118 | 12 | Bauru | 394,254 | ||||

| 3 | Baixada Santista | 1,672,991 | 13 | Presidente Prudente | 357,402 | ||||

| 4 | São José dos Campos | 1,589,875 | 14 | Caraguatatuba–Ubatuba–São Sebastião | 344,383 | ||||

| 5 | Sorocaba | 945,097 | 15 | Limeira | 313,836 | ||||

| 6 | Ribeirão Preto | 861 177 | 16 | Itu–Salto | 302,559 | ||||

| 7 | Jundiaí | 843,633 | 17 | Araraquara | 296,196 | ||||

| 8 | São José do Rio Preto | 660,744 | 18 | São Carlos | 287,035 | ||||

| 9 | Americana–Santa Bárbara d'Oeste | 482,606 | 19 | Mogi Guaçu–Mogi Mirim | 257,511 | ||||

| 10 | Piracicaba | 478,347 | 20 | Indaiatuba | 255,748 | ||||

Religion

Religion in São Paulo (2010)[42][43]

According to the 2010 demographic census, of the total population of the state, there were 24 781 288 Roman Catholics (60.06%), 9 937 853 Protestants or evangelicals (24.08%), 1 356 193 spiritists (3.29%), 444 968 Jehovah's Witnesses (1.08%), 153 564 Buddhists (0.37%), 141 553 Umbanda and Candomblecists (0.34%), 81 810 Brazilian Catholic Apostolic Church (0.20%), 70 856 new Eastern religious (0.17%), 65 556 Mormons (0.16%), 51 050, Jewish (0.12%), 31 618 Orthodox Christians (0.08%), 20 375 spiritualists (0.05%), Esoteric 17 827 (0.04%), 14 778 Islamic (0.04%), 4,591 belonging to indigenous traditions (0.01%) and 1,822 Hindus (0.00%). There were still 3 357 682 people without religion (8.14%), 214 332 with indeterminate religion or multiple membership (0.52%), 50 153 did not know (0.12%) and 18 038 did not declare (0.04%).[42][43]

Crime

São Paulo, as well as other states of Brazil, has two types of police forces to carry out public safety in their territory, the Military Police of São Paulo State (PMESP), the largest police in Brazil and the third largest in Latin America, with 138,000 soldiers,[44] and the Civil Police of the State of São Paulo, which exercises judicial police function and is subordinate to the state government.[45]

According to data from the "Map of Violence 2011", published by the Sangari Institute and the Ministry of Justice, the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants in the state of São Paulo is the lowest in Brazil. The number of homicides in São Paulo fell from 39.7 to 10.1 per 100,000 inhabitants between 1998 and 2014. The state, which occupied the 5th place among the most violent states in the country in 1998, then came to occupy the 27th position in 2016.[46]

In 2019, according to data from the Public Security Secretariat, the state reached a rate of 6.27 homicides per 100 thousand inhabitants, a special reduction compared to the number recorded in 1999, which was 35.27 homicides per 100 thousand inhabitants inhabitants. The state's current homicide rate is below what is considered bearable by the World Health Organization, which is below homicides per 100,000 inhabitants (2023).[47] Other crime rates also fell during the period studied, such as rape, which saw a large reduction.[48]

According to the 2022 Brazilian Security Yearbook, São Paulo has the lowest rate of violent deaths recorded in the country,[49] having 7 of the 10 least violent cities in Brazil.[50]

Health

The state of São Paulo is the country's main health hub, while its capital, the city of São Paulo, has established itself as the Latin American health capital, being the one that receives the most foreigners in search of medical treatments and diagnoses. The city receives patients from all over the world. The first healthcare institution outside the US to receive Joint Commission International (JCI) accreditation was the Albert Einstein hospital.[51]

According to a survey carried out by IBGE in 2013, 71.8% of the population of São Paulo evaluates their health as good or very good — placing the State among those with the highest proportions of people who declared a positive self-rated health; the national average was 66.1%.[52] In 2008, 72.7% of the population reported having regular medical appointments; 45.2% of the inhabitants consult the dentist regularly and 6.5% of the population was admitted to a hospital bed in the last twelve months. 33.7% of the inhabitants reported having a chronic illness and only 40.1% had health insurance. Another significant fact is the fact that 28.9% of the inhabitants declare that they always need the Family Health Unit Program — PUSF.[53]

Regarding female health, 49.7% of women over 40 years of age had a clinical breast exam in the last twelve months; 64.9% of women between 50 and 69 years old had a mammography in the last two years; and 84.4% of women aged 25 to 59 had a cervical cancer screening in the last three years.[53] More recent data from 2012 shows that the birth rate in the state of São Paulo was 14.71 per thousand inhabitants and the mortality rate was 13.17 per thousand live births, one of the lowest in the country.[54]

Education and science

Covered by a significant number of renowned educational institutions and centers of excellence, São Paulo is the largest research and development hub in Brazil, responsible for 52% of Brazilian scientific production and 0.7% of world production in the period between the years 1998 and 2002. Its capital is one of the world's main high-impact science centers.[55] The illiteracy rate indicated by the last IBGE demographic census in 2022 was 2.2%, the 3rd lowest in the country, alongside Santa Catarina.[56] The functional illiteracy rate was 13.2% in 2010.[57] With 15.027 primary schools, 12.539 pre-school units, 5.639 secondary schools and more than 578 universities,[58] the state's education network is the largest in the country.[59]

The HDI education factor in the state in 2005 reached the mark of 0.921 - a very high level, in accordance with the standards of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Among the many higher education institutions, the University of São Paulo (USP) stands out, classified as the best in Latin America and frequently cited among the best universities in the world, reaching 22nd position in 2021;[60][61] the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), the largest producer of research patents in Brazil; the São Paulo State University (UNESP), the 485th best university on the planet and the 16th best in Latin America.[60][62] The three universities, all maintained by the São Paulo government, are maintained by around 10% state revenue from the Tax on Circulation of Goods and Services (ICMS) and by funds from public institutions that promote research, with emphasis on the Fundação de Amparo to Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (formerly the National Research Council, whose acronym, CNPq, was maintained).[63]

Among those maintained by the federal government, the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), the Federal University of ABC (UFABC) and the Technological Institute of Aeronautics (ITA), the latter a center reference in engineering education. The state also has private universities of great national and international reputation, such as the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP), the Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, the Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing (ESPM), the Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP ) and the Education and Research Institute (INSPER).

In addition to many universities, in the field of science and technology, São Paulo has important research institutes, including: Institute for Technological Research (IPT), Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN), Butantan Institute, Biological Institute, Pasteur Institute, the Institute of Medicine Tropical (IMTSP), Forestry Institute, National Institute for Space Research (INPE), National Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNS) and Agronomic Institute of Campinas (IAC).[64]

Educational institutions

This section concentrates unduly on statistical information. |

- Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas e Nucleares (IPEN) (Nuclear and Energy Research Institute, Public);

- Instituto Tecnológico da Aeronáutica (ITA) (Air Force Technological Institute, Public);

- Universidade de São Paulo (USP) (University of São Paulo, Public);

- Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp) (Federal University of São Paulo, Public);

- Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp) (São Paulo State University, Public);

- Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) (University of Campinas, Public);

- Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar) (Federal University of São Carlos, Public);

- Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo (IFSP) (São Paulo Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology, Public);

- Instituto Mauá de Tecnologia (Mauá) (Mauá Institute of Technology, Private);

- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP) (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, Private);

- Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie (Mackenzie) (Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Private);

- Universidade de Sorocaba (UNISO) (University of Sorocaba, Private)

- Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV) (Getúlio Vargas Foundation, Private);

- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas (Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas, Private);

- Universidade Federal do ABC (UFABC) (Federal University of ABC, Public);

- Faculdade de Medicina de Marília (FAMEMA) (Marília Faculty of Medicine, Public);

- Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto (FAMERP) (São José do Rio Preto Faculty of Medicine, Public);

- Universidade Metodista de São Paulo (UMESP) (Methodist University of São Paulo, Private);

- Faculdade de Teologia Metodista Livre (FTML) (Free Methodist College, Private);

- Faculdade de Tecnologia do Estado de São Paulo (FATEC) (São Paulo State Technological College, Public);

- Universidade de Ribeirão Preto (UNAERP) (Ribeirão Preto, Private);

- Universidade de Marília (UNIMAR) (Marília, Private);

- Universidade Paulista (UNIP) (Private)

Government and politics

The Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) held the governorship and the speakership of the state' Legislative Assembly from 1994 to 2022, when governor Rodrigo Garcia, lost the election to Tarcisio de Freitas (Republicanos)

Local politicians of note (with party affiliations) include: former President of Brazil (1994–2002) Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB), former president (2002–2010) Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), José Serra (PSDB), Geraldo Alckmin (PSB), Mário Covas (PSDB), Antonio Palocci (PT), Eduardo Suplicy (PT), Aloizio Mercadante (PT), Marta Suplicy (MDB), Gilberto Kassab (PSD), and Paulo Maluf (PP).

Three of last four Brazilian presidents, Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) and Michel Temer (MDB) were politicians from São Paulo, although Cardoso was actually born in the state of Rio de Janeiro and Lula in Pernambuco. Cardoso and Lula respectively live in the cities of São Paulo and São Bernardo do Campo. The former president Jair Bolsonaro (PL) was born in small town of Glicério, in the state northwest, but built his political career in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

According to the strategist D.L.P.G. da Costa, São Paulo state is geopolitically responsible to split Brazil in two parts, the federal integrated area and the south non-integrated area. Because of its strong self-determination, São Paulo functions as a backup to the rest of Brazil and as a historical pioneer, creating innovations for the rest of the country to sustain its own demands and needs. If it is a fact that on one side São Paulo functions as a geopolitical buffer, blocking the South from a stronger national cohesion, then the other side is also true—a failed São Paulo would probably wreck all of Brazil. At the same time that São Paulo is an anchor whose administration hinders presidential and federal authority, the state of São Paulo also prevents reckless rulers from freely taking complete control of the country and establishing an excessively centralized government. If by one side this is the reason of the south area has feelings for separation by the other side this prevented major economic and political crisis to spread in the same level across the country.[65]

Economy

In 2009 the service sector was the largest component of GDP at 69%, followed by the industrial sector at 31%. Agriculture represents 2% of GDP. The state produces 34% of Brazilian goods and services. São Paulo (state) exports: vehicles 17%, airplanes and helicopters 12%, food industry 10%, sugar and alcohol fuel 8%, orange juice 5%, telecommunications 4% (2002).

São Paulo state is responsible for approximately a third of Brazilian GDP.[68] The state's GDP (PPP) amounts US$1.221 trillion, making it the biggest economy in Latin America and in the Southern Hemisphere.[69] Its economy is based on machinery, the automobile and aviation industries, services, financial companies, commerce, textiles, orange growing, sugar cane and coffee bean production.

São Paulo, one of the largest economic poles in both Latin and South America, has a diversified economy. Some of the largest industries are metal-mechanics, sugar cane, textile and car and aviation manufacturing. Service and financial sectors, as well as the cultivation of oranges, cane sugar and coffee form the basis of an economy which accounts for 34% of Brazil's GDP (equivalent to US$727.053 billion).

The towns of Campinas, Ribeirão Preto, Bauru, São José do Rio Preto, Piracicaba, Jaú, Marilia, Botucatu, Assis, and Ourinhos are important university, engineering, agricultural, zoo-technique, technology, or health sciences centers. The Instituto Butantan in São Paulo is a herpetology serpentary science center that collects snakes and other poisonous animals, as it produces venom antidotes. The Instituto Pasteur produces medical vaccines. The state is also at the vanguard of ethanol production, soybeans, aircraft construction in São José dos Campos, and its rivers have been important in generating electricity through its hydroelectric plants.

Moreover, São Paulo is one of the world's most important sources of beans, rice, oranges and other fruit, coffee, sugar cane, alcohol, flowers and vegetables, maize, cattle, swine, milk, cheese, wine, and oil producers. Textile and manufacturing centers such as Rua José Paulino and 25 de Março in São Paulo city is a magnet for retail shopping and shipping that attracts customers from the whole country and as far as Cape Verde and Angola in Africa.

Primary sector

In agriculture, it is a giant producer of sugar cane and oranges, and also has large production of coffee, soy, maize, bananas, peanuts, lemons, persimmons, tangerines, cassavas, carrots, potatoes and strawberries.

In 2019, São Paulo produced 425,617,093 tons of sugar cane.[70] São Paulo production is equivalent to 56.5% of the Brazilian production of 752,895,389 tons, exceeds the production of India (2nd largest world producer of cane) in 2019 (which was 405,416,180 tons) and was equivalent to 21.85% of the world cane production in the same year (1,949,310,108 tons).[71][72][73][74]

In 2019, São Paulo produced 13,256,246 tons of oranges.[75] São Paulo production is equivalent to 78% of Brazilian production of 17,073,593 tons, exceeds the production of China (2nd largest orange producer in the world) of 2019 (which was 10,435,719 tons) and was equivalent to 16.84% of world production of orange in the same year (78,699,604 tons). Most of it is destined for the industrialization and export of juice.[71]

In 2017, São Paulo represented 9.8% of the total national production of coffee (third place).[72][76]

The state of São Paulo concentrates more than 90% of the national production of peanuts, and Brazil exports around 30% of the peanuts it produces.[77]

São Paulo is also the largest national producer of banana, with 1 million tons in 2018. The country produced 6.7 million tons this year. Brazil was already the 2nd largest producer of the fruit in the world, currently in 3rd place, losing only to India and Ecuador.[78][79]

The cultivation of soy, on the other hand, is increasing, however, it is not among the largest national producers of this grain. In the 2018–2019 harvest, São Paulo harvested 3 million tons (Brazil produced 120 million).[80]

São Paulo also has a considerable production of maize (corn). In 2019, it produced almost 2 million tons. It is the sixth largest producer of this grain in Brazil. State demand is estimated at 9 million tons, for animal feed, which requires the State of São Paulo to buy corn from other units of the Federation.[81]

In the production of cassava, Brazil produced a total of 17.6 million tons in 2018. São Paulo was the third largest producer in the country, with 1.1 million tons.[82]

In 2018, São Paulo was the largest producer of tangerines in Brazil. About persimmons, São Paulo is the largest producer in the country with 58%. The Southeast is the largest producer of lemons in the country, with 86% of the total obtained in 2018. Only the state of São Paulo produces 79% of the total.[83][84][85]

In 2019, in Brazil, there was a total production area of around 4 thousand hectares of strawberries. São Paulo ranked second in Brazil with 800 hectares, with production concentrated in the municipalities of Piedade, Campinas, Jundiaí, Atibaia and nearby municipalities.[86]

With regard to carrots, Brazil ranked fifth in the world ranking in 2016, with an annual production of around 760 thousand tons. In relation to the exports of this product, Brazil occupies the seventh world position. Minas Gerais and São Paulo are the 2 largest producers in Brazil. In São Paulo, the producing municipalities are Piedade, Ibiúna and Mogi das Cruzes. As for potatoes, the main national producer is the state of Minas Gerais, with 32% of the total produced in the country. In 2017, Minas Gerais harvested around 1.3 million tons of the product. São Paulo owns 24% of the production.[87][88][89][90]

Regarding the bovine herd, in 2019 São Paulo had approximately 10.3 million head of cattle (6.1 million for beef, 1 million for milk production, 3 million for both). The production of milk this year was 1.78 billion liters. The number of birds to lay eggs was 56.49 million heads. Production of eggs was 1.34 billion dozen. The State of São Paulo is the largest national producer with 29.4%. In the production of poultry for production in São Paulo, there was a production of 690.96 million heads in 2019, equivalent to an offer of 1.57 million tons of chicken. The number of pigs in the state in 2019 is 929.62 thousand heads. Production was 1.46 million head, or 126 thousand tons of pork.[91]

In 2018, when it comes to chickens, the first ranking region was the Southeast, with 38.9% of the total head of the country. A total of 246.9 million chickens were estimated for 2018. The state of São Paulo was responsible for 21.9%. The national production of chicken eggs was 4.4 billion dozen in 2018. The Southeast region was responsible for 43.8% of the total produced. The state of São Paulo was the largest national producer (25.6%). The number of quail was 16.8 million birds. The Southeast is responsible for 64%, highlighting São Paulo (24.6%).[92]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=State_of_São_PauloText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk