A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Sushruta Samhita (Sanskrit: सुश्रुतसंहिता, lit. 'Suśruta's Compendium', IAST: Suśrutasaṃhitā) is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and one of the most important such treatises on this subject to survive from the ancient world. The Compendium of Suśruta is one of the foundational texts of Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine), alongside the Charaka-Saṃhitā, the Bhela-Saṃhitā, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript.[1][2] It is one of the two foundational Hindu texts on the medical profession that have survived from ancient India.[3]

The Suśrutasaṃhitā is of great historical importance because it includes historically unique chapters describing surgical training, instruments and procedures. [2][4][page needed] One of the oldest Sushruta Samhita palm-leaf manuscripts is preserved at the Kaiser Library, Nepal.[5]

History

Ancient qualifications of a Nurse

That person alone is fit to nurse or to attend the bedside of a patient, who is cool-headed and pleasant in his demeanor, does not speak ill of any body, is strong and attentive to the requirements of the sick, and strictly and indefatigably follows the instructions of the physician.

—Sushruta Samhita Book 1, Chapter XXXIV

Translator: Bhishagratna[6]

Date

The most detailed and extensive consideration of the date of the Suśrutasaṃhitā is that published by Meulenbeld in his History of Indian Medical Literature (1999-2002). Meulenbeld states that the Suśrutasaṃhitā is likely a work that includes several historical layers, whose composition may have begun in the last centuries BCE and was completed in its presently surviving form by another author who redacted its first five sections and added the long, final section, the "Uttaratantra."[1] It is likely that the Suśruta-saṃhitā was known to the scholar Dṛḍhabala (fl. 300-500 CE), which gives the latest date for the version of the work that has survived into the modern era.[1]

In Suśrutasaṃhitā - A Scientific Synopsis, the historians of Indian science Ray, Gupta and Roy noted the following view, which is broadly the same as Meulenbeld's:[7]

"The Chronology Committee of the National Institute of Sciences of India (Proceedings, 1952),[8] was of the opinion that third to fourth centuries A. D. may be accepted as the date of the recension of the Suśruta Saṃhitā by Nāgārjuna, which formed the basis of Dallaṇa's commentary."

The above view remains the consensus amongst university scholars of the history of Indian medicine and Sanskrit literature.

Hoernle's view

Regrettably, given its subsequent influence, the scholar Rudolf Hoernle (1841 – 1918) proposed in 1907 that because the author of Satapatha Brahmana, a Vedic text from the mid-first-millennium BCE, was aware of Sushruta's doctrines, Sushruta's work should be dated based on the composition date of Satapatha Brahmana.[9] The composition date of the Brahmana was itself unclear, added Hoernle, but he estimated it to be about the sixth century BCE.[9]

Unfortunately, Hoernle's date of 600 BCE for the Suśrutasaṃhitā continues to be widely and uncritically cited in spite of much intervening scholarship over the last century. Yet, because of further research, scores of scholars have subsequently published more considered opinions on the date of the work, and this scholarship has been summarized by Meulenbeld in his History of Indian Medical Literature.[10] It has become clear that Hoernle's dating was wrong by more than 500 years.

Central to the problem of chronology is the fact that the Suśrutasaṃhitā is the work of several hands. The internal tradition recorded in manuscript colophons and by medieval commentators makes clear that an old version of the Suśrutasaṃhitā consisted of sections 1-5, with the sixth part having been added by a later author. However, the oldest manuscripts we have of the work already include the sixth section, called "The Later Book" (Skt. Uttara-tantra). Manuscript colophons routinely call the whole work "The Suśrutasaṃhitā together with the Uttara-tantra," reinforcing the idea that this was perceived as a five+one composition. Thus, it does not make sense to speak of "the date of Suśruta." Like "Hippocrates," the name "Suśruta" refers to the work of many authors working over several centuries.

Further views on chronology

As mentioned above, scores of scholars have proposed hypotheses on the formation and dating of the Suśrutasaṃhitā, ranging from 2000 BCE to the sixth century CE. These views have been gathered and neutrally described by the medical historian Jan Meulenbeld.[11]

Authorship

Sushruta or Suśruta (Sanskrit: सुश्रुत, IAST: Suśruta, lit. 'well heard',[12] an adjective meaning "renowned"[13]) is named in the text as the author, who is presented in later manuscripts and printed editions a narrating the teaching of his guru, Divodāsa.[14][15] Early Buddhist Jatakas mention a Divodāsa as a physician who lived and taught in ancient Kashi (Varanasi).[10] The earliest known mentions of the name Suśruta firmly associated with the tradition of the Suśrutasaṃhitā is in the Bower Manuscript (4th or 5th century CE), where Suśruta is listed as one of the ten sages residing in the Himalayas.[16]

After a review of all past scholarship on the identity of Suśruta, Meulenbeld concluded that:

As is obvious from the foregoing, it is rather generally assumed that we owe the main part of the Suśrutasaṃhitā or an earlier verion of it to a historical person called Suśruta. This assumption, however, is not based on uncontrovertible evidence and may be illusroy. The text of the Suśrutasaṃhitā does not warrant that the one who composed it was a Suśruta. The structure oif the treatise shows without ambiguity that the aythor, who created a coherent whole out of earlier mateiral, attributed the teachings incorporated in his work to Kāśirāja Divodāsa...[17]

Religious affiliation

The text has been called a Hindu text by many scholars.[18][19][20] The text discusses surgery with the same terminology found in more ancient Hindu texts,[21][22] mentions Hindu gods such as Narayana, Hari, Brahma, Rudra, Indra and others in its chapters,[23][24] refers to the scriptures of Hinduism namely the Vedas,[25][26] and in some cases, recommends exercise, walking and "constant study of the Vedas" as part of the patient's treatment and recovery process.[27] The text also uses terminology of Vaiśeṣika, Samkhya and other schools of Hindu philosophy.[28][29][30]

The Sushruta Samhita and Caraka Samhita have religious ideas throughout, states Steven Engler, who then concludes "Vedic elements are too central to be discounted as marginal".[30] These ideas include the use of terms and same metaphors that are variously pervasive in Buddhist and Hindu scriptures – the Vedas, and the inclusion of theory of Karma, self (Atman) and Brahman (metaphysical reality) along the lines of those found in ancient Hindu and Buddhist texts.[30] However, adds Engler, the text also includes another layer of ideas, where empirical rational ideas flourish in competition or cooperation with religious ideas.[30] Following Engler's study, contemporary scholars have abandoned the distinction "religious" vs. "empirico-rational" as no longer being a useful analytical distinction.

The text may have Buddhist influences, since a redactor named Nagarjuna has raised many historical questions, although he cannot have been the person of Mahayana Buddhism fame.[31] Zysk produced evidence that the medications and therapies mentioned in the Pāli Canon bear strong resemblances and are sometimes identical to those of the Suśrutasaṃhitā and the Carakasaṃhitā.[32]

In general, states Zysk, Buddhist medical texts are closer to Sushruta than to Caraka,[33] and in his study suggests that the Sushruta Samhita probably underwent a "Hinduization process" around the end of 1st millennium BCE and the early centuries of the common era after the Hindu orthodox identity had formed.[34] Clifford states that the influence was probably mutual, with Buddhist medical practice in its ancient tradition prohibited outside of the Buddhist monastic order by a precedent set by Buddha, and Buddhist text praise Buddha instead of Hindu gods in their prelude.[35] The mutual influence between the medical traditions between the various Indian religions, the history of the layers of the Suśruta-saṃhitā remains unclear, a large and difficult research problem.[31]

Sushruta is reverentially held in Hindu tradition to be a descendant of Dhanvantari, the mythical god of medicine,[36] or as one who received the knowledge from a discourse from Dhanvantari in Varanasi.[14]

Manuscripts and transmission

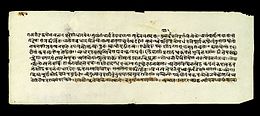

One of the oldest palm-leaf manuscripts of Sushruta Samhita has been discovered in Nepal. It is preserved at the Kaiser Library, Nepal as manuscript KL–699. A microfilm copy of the MS was created by Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project (NGMCP C 80/7) and is stored in the National Archives, Kathmandu.[5] The partially damaged manuscript consists of 152 folios, written on both sides, with 6 to 8 lines in transitional Gupta script. The manuscript has been verifiably dated to have been completed by the scribe on Sunday, April 13, 878 CE (Manadeva Samvat 301).[5]

Much of the scholarship on the Suśruta-saṃhitā is based on editions of the text that were published during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This includes the important edition by Vaidya Yādavaśarman Trivikramātmaja Ācārya that also includes the commentary of the scholar Dalhaṇa.[37]

The printed editions are based on the small subset of surviving manuscripts that was available in the major publishing centers of Bombay, Calcutta and elsewhere when the editions were being prepared — sometimes as few as three or four manuscripts. But these do not adequately represent the large number of manuscript versions of the Suśruta-saṃhitā that have survived into the modern era. Taken together, all printed versions of the Suśrutasaṃhitā are based on no more than ten percent of the more than 230 manuscripts of the work that exist today.[38]

Contents

Anatomy and empirical studies

The different parts or members of the body as mentioned before including the skin, cannot be correctly described by one who is not well versed in anatomy. Hence, any one desirous of acquiring a thorough knowledge of anatomy should prepare a dead body and carefully, observe, by dissecting it, and examine its different parts.

—Sushruta Samhita, Book 3, Chapter V

Translators: Loukas et al[39]

The Sushruta Samhita is among the most important ancient medical treatises.[1] It is one of the foundational texts of the medical tradition in India, alongside the Caraka-Saṃhitā, the Bheḷa-Saṃhitā, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript.[1][2]

Scope

The Sushruta Samhita was perhaps composed after Charaka Samhita and, except for some topics and their emphasis, both discuss many similar subjects such as General Principles, Pathology, Diagnosis, Anatomy, Sensorial Prognosis, Therapeutics, Pharmaceutics and Toxicology.[40][41][1]

The Sushruta and Charaka texts differ in one major aspect, with Sushruta Samhita providing more detailed descriptions of surgery, surgical instruments and surgical training. The Charaka Samhita mentions surgery, but only briefly.

Chapters

The Sushruta Samhita, in its extant form, is divided into 186 chapters and contains descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, 700 medicinal plants, 64 preparations from mineral sources and 57 preparations based on animal sources.[42]

The Suśruta-Saṃhitā is divided into two parts: the first five books (Skt. Sthanas) are considered to be the oldest part of the text, and the "Later Section" (Skt. Uttaratantra) that was added by the author Nagarjuna.[43] The content of these chapters is diverse, some topics are covered in multiple chapters in different books, and a summary according to the Bhishagratna's translation is as follows:[44][45][46]

| Book | Chapter | Topics (incomplete)[note 1] | Translation Comments | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||