A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Niall Ferguson | |

|---|---|

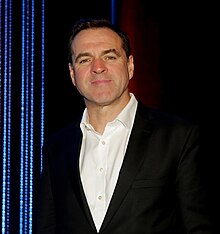

Ferguson in 2017 | |

| Born | Niall Campbell Ferguson 18 April 1964 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Citizenship |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5 |

| Academic background | |

| Education | Magdalen College, Oxford (MA, DPhil) University of Hamburg |

| Thesis | Business and Politics in the German Inflation (1989) |

| Doctoral advisor | Norman Stone |

| Influences | A. J. P. Taylor |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | International history Economic history |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | Tyler Goodspeed |

| Notable works | Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World (2003) Civilisation: the West and the Rest (2011) |

| Website | www |

Niall Campbell Ferguson FRSE (/ˈniːl/; born 18 April 1964)[1] is a Scottish–American historian who is the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a senior fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University.[2][3] Previously, he was a professor at Harvard University, the London School of Economics, New York University, a visiting professor at the New College of the Humanities, and a senior research fellow at Jesus College, Oxford.

Ferguson writes and lectures on international history, economic history, financial history and the history of the British Empire and American imperialism.[4] He holds positive views concerning the British Empire.[5] In 2004, he was one of Time magazine's 100 most influential people in the world.[6] Ferguson has written and presented numerous television documentary series, including The Ascent of Money, which won an International Emmy Award for Best Documentary in 2009.[7]

Ferguson has been a contributing editor for Bloomberg Television[8] and a columnist for Newsweek. He began writing a semi-monthly column for Bloomberg Opinion in June 2020.[9]

Early life and education

Ferguson was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on 18 April 1964 to James Campbell Ferguson, a doctor, and Molly Archibald Hamilton, a physics teacher.[10][11] Ferguson grew up in the Ibrox area of Glasgow in a home close to the Ibrox Park football stadium.[12][13] He attended The Glasgow Academy.[14] He was brought up as—and remains (as of the last version of this article) —an atheist, though he has encouraged his children to study religion and attends church occasionally.[15]

In a 2023 interview,[16] however, Ferguson declares: "I'm a lapsed atheist... I go to church every Sunday, precisely because having been brought up as an atheist, I came to realise in my career as a historian that not only is atheism a disastrous basis for a society... but also because I don't think it can be a basis for individual ethical decision making".

Ferguson cites his father as instilling in him a strong sense of self-discipline and of the moral value of work, while his mother encouraged his creative side.[17] His maternal grandfather, a journalist, encouraged him to write.[17] He has described his parents as "both very much products of the Scottish Enlightenment."[13] Ferguson ascribes his decision to read history at university instead of English literature to two main factors: Leo Tolstoy's reflections on history at the end of War and Peace (which he read at the age of fifteen)[citation needed], and his admiration of historian A. J. P. Taylor.

Oxford

Ferguson received a demyship (highest scholarship) from Magdalen College, Oxford.[18] Whilst a student there, he wrote a 90-minute student film The Labours of Hercules Sprote, played double bass in a jazz band "Night in Tunisia", edited the student magazine Tributary, and befriended Andrew Sullivan, who shared his interest in right-wing politics and punk music.[19] He had become a Thatcherite by 1982. He graduated with a first-class honours degree in history in 1985.[18][citation needed]

Ferguson studied as a Hanseatic Scholar at the University of Hamburg from 1986 until 1988. He received his Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Oxford in 1989. His dissertation was titled "Business and Politics in the German Inflation: Hamburg 1914–1924".[20]

Career

Academic career

In 1989, Ferguson worked as a research fellow at Christ's College, Cambridge. From 1990 to 1992 he was an official fellow and lecturer at Peterhouse, Cambridge. He then became a fellow and tutor in modern history at Jesus College, Oxford, where in 2000 he was named a professor of political and financial history. In 2002 Ferguson became the John Herzog Professor in Financial History at New York University Stern School of Business, and in 2004 he became the Laurence A. Tisch Professor of History at Harvard University and William Ziegler Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. From 2010 to 2011, Ferguson held the Philippe Roman Chair in history and international affairs at the London School of Economics.[21] In 2016 Ferguson left Harvard[22] to become a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he had been an adjunct fellow since 2005.

Ferguson has received honorary degrees from the University of Buckingham, Macquarie University (Australia) and Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez (Chile). In May 2010, Michael Gove, education secretary, asked Ferguson to advise on the development of a new history syllabus, to be entitled "history as a connected narrative", for schools in England and Wales.[23][24] In June 2011, he joined other academics to set up the New College of the Humanities, a private college in London.[25]

In the same year emails were released to the public and university administrators which documented Ferguson's attempts to discredit a progressive activist student at Stanford University who had been critical of Ferguson's choices of speakers invited to the Cardinal Conversations free speech initiative.[26] He teamed with a Republican student group to find information that might discredit the student. Ferguson resigned from leadership of the program once university administrators became aware of his actions.[26][27]

Ferguson responded in his column[28] saying, "Re-reading my emails now, I am struck by their juvenile, jocular tone. "A famous victory," I wrote the morning after the Murray event. 'Now we turn to the more subtle game of grinding them down on the committee. The price of liberty is eternal vigilance.' Then I added: 'Some opposition research on Mr O might also be worthwhile'—a reference to the leader of the protests. None of this happened. The meetings of the student committee were repeatedly postponed. No one ever did any digging on "Mr O". The spring vacation arrived. The only thing that came of the emails was that their circulation led to my stepping down."

Business career

In 2000 Ferguson was a founding director of Boxmind,[29] an Oxford-based educational technology company.

In 2006 he set up Chimerica Media Ltd.,[30] a London-based television production company.

In 2007 Ferguson was appointed as an investment management consultant by GLG Partners, to advise on geopolitical risk as well as current structural issues in economic behaviour relating to investment decisions.[31] GLG is a UK-based hedge fund management firm headed by Noam Gottesman.[32] Ferguson was also an adviser to Morgan Stanley, the investment bank.

In 2011 he set up Greenmantle LLC, an advisory business specializing in macroeconomics and geopolitics.[citation needed] He also serves as a non-executive director on the board of Affiliated Managers Group.[citation needed]

Political involvement

Ferguson was an advisor to John McCain's U.S. presidential campaign in 2008, supported Mitt Romney in his 2012 campaign, and was a vocal critic of Barack Obama.[33][34]

Non-profit organisation

Ferguson is a trustee of the New-York Historical Society and the London-based Centre for Policy Studies.[citation needed]

Career as a commentator, documentarian and public intellectual

Ferguson has written regularly for British newspapers and magazines since the mid 1980s. At that time, he was lead writer for The Daily Telegraph, and a regular book reviewer for The Daily Mail. In the summer of 1989, while travelling in Berlin, he wrote an article for a British newspaper with the provisional headline "The Berlin Wall is Crumbling", but it was not published.[35] In the early 2000s he wrote a weekly column for The Sunday Telegraph and Los Angeles Times,[36] leaving in 2007 to become a contributing editor to the Financial Times.[37][38] Between 2008 and 2012 he wrote regularly for Newsweek.[23] Since 2015 he has written a weekly column for The Sunday Times and The Boston Globe, which also appears in numerous papers around the world.

Ferguson's television series The Ascent of Money[39] won the 2009 International Emmy award for Best Documentary.[7] In 2011, his film company Chimerica Media released its first feature-length documentary, Kissinger, which won the New York Film Festival's prize for Best Documentary.

In an interview with Peter Robinson, Ferguson recounted the "humiliation" his wife, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, endured at being disinvited from giving the commencement address at Brandeis University in 2014.[40][41] Observing this to being a recurring phenomena as "a curious illiberal turn" for universities— including Harvard where he was teaching—made him a critic of cancel culture.[40][42] Prospect has since described him as one of the most prominent supporters of anti cancel-culture.[42] Ferguson's main target here seems to be the academe, saying, "Wokeism has gone from being a fringe fashion to be the dominant ideology of the universities."[40][43]

Television documentaries

- Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World (2003)

- American Colossus (2004)

- The War of the World (2006)

- The Ascent of Money (2008)

- Civilization: Is the West History? (2011)

- Kissinger (2011)

- China: Triumph and Turmoil (2012)

- The Pity of War (2014)

- Networld (2020)

BBC Reith Lectures

In May 2012 the BBC announced Niall Ferguson was to present its annual Reith Lectures. These four lectures, titled The Rule of Law and its Enemies, examine the role man-made institutions have played in the economic and political spheres.[44]

In the first lecture, held at the London School of Economics, titled The Human Hive, Ferguson argues for greater openness from governments, saying they should publish accounts which clearly state all assets and liabilities. Governments, he said, should also follow the lead of business and adopt the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and, above all, generational accounts should be prepared on a regular basis to make absolutely clear the inter-generational implications of current fiscal policy. In the lecture, Ferguson says young voters should be more supportive of government austerity measures if they do not wish to pay further down the line for the profligacy of the baby boomer generation.[45]

In the second lecture, The Darwinian Economy, Ferguson reflects on the causes of the global financial crisis, and allegedly erroneous conclusions that many people have drawn from it about the role of regulation, and asks whether regulation is in fact "the disease of which it purports to be the cure".

The Landscape of Law was the third lecture, delivered at Gresham College. It examines the rule of law in comparative terms, asking how far the common law's claims to superiority over other systems are credible, and whether we are living through a time of "creeping legal degeneration" in the English-speaking world.

The fourth and final lecture, Civil and Uncivil Societies, focuses on institutions (outside the political, economic and legal realms) designed to preserve and transmit particular knowledge and values. Ferguson asks whether the modern state is quietly killing civil society in the Western world, and what non-Western societies can do to build a vibrant civil society.

The first lecture was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and the BBC World Service on Tuesday, 19 June 2012.[46] The series is available as a BBC podcast.[47]

Books

The Cash Nexus

In his 2001 book, The Cash Nexus, which he wrote following a year as Houblon-Norman Fellow at the Bank of England,[38] Ferguson argues that the popular saying, "money makes the world go 'round", is wrong; instead he presented a case for human actions in history motivated by far more than just economic concerns.

Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World

In his 2003 book, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, Ferguson conducts a provocative reinterpretation of the British Empire, casting it as one of the world's great modernising forces. The Empire produced durable changes and globalisation with steampower, telegraphs, and engineers.[48][49]

Bernard Porter, famous for expressing his views during the Porter–MacKenzie debate on the British Empire, attacked Empire in The London Review of Books as a "panegyric to British colonialism".[50] Ferguson, in response to this, drew Porter's attention to the conclusion of the book, where he writes: "No one would claim that the record of the British Empire was unblemished. On the contrary, I have tried to show how often it failed to live up to its own ideal of individual liberty, particularly in the early era of enslavement, transportation and the 'ethnic cleansing' of indigenous peoples." Ferguson argues however that the British Empire was preferable to German and Japanese rule at the time:

The 19th-century empire undeniably pioneered free trade, free capital movements and, with the abolition of slavery, free labour. It invested immense sums in developing a global network of modern communications. It spread and enforced the rule of law over vast areas. Though it fought many small wars, the empire maintained a global peace unmatched before or since. In the 20th century too the empire more than justified its own existence. For the alternatives to British rule represented by the German and Japanese empires were clearly—and they admitted it themselves—far worse. And without its empire, it is inconceivable that Britain could have withstood them.[50]

The book was the subject for a documentary series on British television network Channel 4.

Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire

In his 2005 book, Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire, Ferguson proposes that the United States aspires to globalize free markets, the rule of law, and representative government, but shies away from the long-term commitments of manpower and money that are indispensable, in taking a more active role in resolving conflict arising from the failure of states.[51] The U.S. is an empire in denial, not acknowledging the scale of global responsibilities.[52] The American writer Michael Lind, responding to Ferguson's advocation of an enlarged American military through conscription, accused Ferguson of engaging in apocalyptic alarmism about the possibility of a world without the United States as the dominant power and of a casual disregard for the value of human life.[53]

War of the World

In War of the World, published in 2006, Ferguson argued that a combination of economic volatility, decaying empires, psychopathic dictators, racially/ethnically motivated and institutionalised violence resulted in the wars and genocides of what he calls "History's Age of Hatred". The New York Times Book Review named War of the World one of the 100 Notable Books of the Year in 2006, while the International Herald Tribune called it "one of the most intriguing attempts by an historian to explain man's inhumanity to man".[54]

Ferguson addresses the paradox that, though the 20th century was "so bloody", it was also "a time of unparalleled progress". As with his earlier work Empire, War of the World was accompanied by a Channel 4 television series presented by Ferguson.[55]

The Ascent of Money

Published in 2008, The Ascent of Money examines the history of money, credit, and banking. In it, Ferguson predicts a financial crisis as a result of the world economy and in particular the United States using too much credit. He cites the China–United States dynamic which he refers to as Chimerica where an Asian "savings glut" helped create the subprime mortgage crisis with an influx of easy money.[56]

Civilization

Published in 2011, Civilization: The West and the Rest examines what Ferguson calls the most "interesting question" of our day: "Why, beginning around 1500, did a few small polities on the western end of the Eurasian landmass come to dominate the rest of the world?" [57]

The Economist in a review wrote:

In 1500 Europe's future imperial powers controlled 10% of the world's territories and generated just over 40% of its wealth. By 1913, at the height of empire, the West controlled almost 60% of the territories, which together generated almost 80% of the wealth. This stunning fact is lost, he regrets, on a generation that has supplanted history's sweep with a feeble-minded relativism that holds "all civilisations as somehow equal".[58]

Ferguson attributes this divergence to the West's development of six "killer apps", which he finds were largely missing elsewhere in the world in 1500 – "competition, the scientific method, the rule of law, modern medicine, consumerism and the work ethic".[23]

Ferguson compared and contrasted how the West's "killer apps" allowed the West to triumph over "the Rest" citing examples.[58] Ferguson argued the rowdy and savage competition between European merchants created far more wealth than did the static and ordered society of Qing China. Tolerance extended to thinkers like Sir Isaac Newton in Stuart England had no counterpart in the Ottoman Empire, where Takiyuddin's state built observatory was eventually demolished due to political conflict. This ensured that Western civilization was capable of making scientific advances that Ottoman civilization never could. Respect for private property was far stronger in British America than it ever was in Spanish America, which led to the United States and Canada becoming prosperous societies while Latin America was and remains mired in poverty.[58]

Ferguson also argued that the modern West had lost its edge and the future belongs to the nations of Asia, especially China, which has adopted the West's "killer apps".[58] Ferguson argues that in the coming years, we will see a steady decline of the West, while China and the rest of the Asian nations will be the rising powers.[58]

A related documentary Civilization: Is the West History? was broadcast as a six-part series on Channel 4 in March and April 2011.[59]

Kissinger: 1923–1968: The Idealist

Kissinger The Idealist, Volume I, published in September 2015, is the first part of a planned two-part biography of Henry Kissinger based on his private papers. The book starts with a quote from a letter which Kissinger wrote in 1972. The book examines Kissinger's life from being a refugee and fleeing Nazi Germany in 1938, to serving in the US army as a "free man" in World War II, to studying at Harvard. The book explores the history of Kissinger joining the Kennedy administration and later becoming critical of its foreign policy, to supporting Nelson Rockefeller on three failed presidential bids, to joining the Nixon administration. The book includes Kissinger's early evaluation of the Vietnam War and his efforts to negotiate with the North Vietnamese in Paris.

Historians and political scientists gave the book mixed reviews.[60][61] The Economist wrote in a review about The Idealist: "Mr Ferguson, a British historian also at Harvard, has in the past sometimes produced work that is rushed and uneven. Not here. Like Mr Kissinger or loathe him, this is a work of engrossing scholarship."[62] In a negative review of The Idealist, the American journalist Michael O'Donnell questioned Ferguson's interpretation of Kissinger's actions leading up to Nixon's election as President.[63]

Andrew Roberts praised the book in The New York Times,[64] concluding: "Niall Ferguson already has many important, scholarly and controversial books to his credit. But if the second volume of "Kissinger" is anywhere near as comprehensive, well written and riveting as the first, this will be his masterpiece."

The Square and the Tower

In 2018's The Square and the Tower, Ferguson proposed a modified version of group selection that history can be explained by the evolution of human networks. He wrote, "Man, with his unrivaled neural network, was born to network."[65] The title refers to a transition from hierarchical, "tower" networks to flatter, "square" network connections between individuals. John Gray in a review of the book was not convinced. He wrote, "He offers a mix of metaphor and what purports to be a new science."[66]

"Niall Ferguson has again written a brilliant book," wrote Deirdre McCloskey in The Wall Street Journal,[67] "this time in defence of traditional top-down principles of governing the wild market and the wilder international order. The Square and the Tower raises the question of just how much the unruly world should be governed – and by whom. Not everyone will agree, but everyone will be charmed and educated. ... "The Square and the Tower" is always readable, intelligent, original. You can swallow a chapter a night before sleep and your dreams will overflow with scenes of Stendhal's "The Red and the Black," Napoleon, Kissinger. In 400 pages you will have restocked your mind. Do it."

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe

In this book, Ferguson offers a global history of disaster. Damon Linker of The New York Times argues that the book is "often insightful, productively provocative and downright brilliant" and suggests that Ferguson displays "an impressive command of the latest research in a large number of specialized fields, among them medical history, epidemiology, probability theory, cliodynamics and network theory."[68] However Linker also criticises the book's "perplexing lacunae."[68]

In a review for The Times, David Aaronovitch described Ferguson's theory as "nebulous."[69]

Opinions, views and research

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|