A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Roman Empire

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 BC–AD 395 (unified)[1] AD 395–476/480 (Western) AD 395–1453 (Eastern) | |||||||||||

Roman Empire in AD 117 at its greatest extent, at the time of Trajan's death | |||||||||||

Roman territorial evolution from the rise of the city-state of Rome to the fall of the Western Roman Empire | |||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Roman | ||||||||||

| Government | Semi-elective absolute monarchy (de facto) | ||||||||||

• Emperor | (List) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical era to Late Middle Ages (Timeline) | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 25 BC[15] | 2,750,000 km2 (1,060,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| AD 117[15][16] | 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| AD 390[15] | 3,400,000 km2 (1,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 25 BC[17] | 56,800,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Sestertius,[e] aureus, solidus, nomisma | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Roman Empire[a] was the post-Republican state of ancient Rome. It is generally understood to mean the period and territory ruled by the Romans following Octavian's assumption of sole rule under the Principate in 27 BC. It included territories in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia and was ruled by emperors. The fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD conventionally marks the end of classical antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

Rome had expanded its rule to most of the Mediterranean and beyond. However, it was severely destabilized by civil wars and political conflicts, which culminated in the victory of Octavian over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and the subsequent conquest of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt. In 27 BC, the Roman Senate granted Octavian overarching power (imperium) and the new title of Augustus, marking his accession as the first Roman emperor of a monarchy with Rome as its sole capital. The vast Roman territories were organized into senatorial provinces, governed by proconsuls who were appointed by lot annually, and imperial provinces, which belonged to the emperor but were governed by legates.[19]

The first two centuries of the Empire saw a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity known as the Pax Romana (lit. 'Roman Peace'). Rome reached its greatest territorial extent under Trajan (r. 98–117 AD– ); a period of increasing trouble and decline began under Commodus (180–192). In the 3rd century, the Empire underwent a crisis that threatened its existence, as the Gallic and Palmyrene Empires broke away from the Roman state, and a series of short-lived emperors led the Empire. It was reunified under Aurelian (r. 270–275). Diocletian set up two different imperial courts in the Greek East and Latin West in 286; Christians rose to power in the 4th century after the Edict of Milan. The imperial seat moved from Rome to Byzantium in 330, renamed Constantinople after Constantine the Great. The Migration Period, involving large invasions by Germanic peoples and by the Huns of Attila, led to the decline of the Western Roman Empire. With the fall of Ravenna to the Germanic Herulians and the deposition of Romulus Augustus in 476 AD by Odoacer, the Western Roman Empire finally collapsed. The Eastern Roman Empire survived for another millennium with Constantinople as its sole capital, until the city's fall in 1453.[f]

Due to the Empire's extent and endurance, its institutions and culture had a lasting influence on the development of language, religion, art, architecture, literature, philosophy, law, and forms of government across its territories. Latin evolved into the Romance languages while Medieval Greek became the language of the East. The Empire's adoption of Christianity resulted in the formation of medieval Christendom. Roman and Greek art had a profound impact on the Italian Renaissance. Rome's architectural tradition served as the basis for Romanesque, Renaissance and Neoclassical architecture, influencing Islamic architecture. The rediscovery of classical science and technology (which formed the basis for Islamic science) in medieval Europe contributed to the Scientific Renaissance and Scientific Revolution. Many modern legal systems, such as the Napoleonic Code, descend from Roman law. Rome's republican institutions have influenced the Italian city-state republics of the medieval period, the early United States, and modern democratic republics.

History

Transition from Republic to Empire

Rome had begun expanding shortly after the founding of the Roman Republic in the 6th century BC, though not outside the Italian peninsula until the 3rd century BC. Thus, it was an "empire" (a great power) long before it had an emperor.[21] The Republic was not a nation-state in the modern sense, but a network of self-ruled towns (with varying degrees of independence from the Senate) and provinces administered by military commanders. It was governed by annually elected magistrates (Roman consuls above all) in conjunction with the Senate.[22] The 1st century BC was a time of political and military upheaval, which ultimately led to rule by emperors.[23][24][25] The consuls' military power rested in the Roman legal concept of imperium, meaning "command" (though typically in a military sense).[26] Occasionally, successful consuls were given the honorary title imperator (commander); this is the origin of the word emperor, since this title was always bestowed to the early emperors.[27]

Rome suffered a long series of internal conflicts, conspiracies, and civil wars from the late second century BC (see Crisis of the Roman Republic) while greatly extending its power beyond Italy. In 44 BC Julius Caesar was briefly dictator before being assassinated. The faction of his assassins was driven from Rome and defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC by Mark Antony and Caesar's adopted son Octavian. Antony and Octavian's division of the Roman world did not last and Octavian's forces defeated those of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In 27 BC the Senate made Octavian princeps ("first citizen") with proconsular imperium, thus beginning the Principate (the first epoch of Roman imperial history, usually dated from 27 BC to 284 AD), and gave him the title Augustus ("the venerated"). Although the republic stood in name, Augustus had all meaningful authority.[28] Since his rule began an unprecedented period of peace and prosperity, he was so loved that he came to hold the power of a monarch de facto if not de jure. During the years of his rule, a new constitutional order emerged (in part organically and in part by design), so that, upon his death, this new constitutional order operated as before when Tiberius was accepted as the new emperor.[citation needed]

Pax Romana

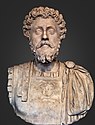

The 200 years that began with Augustus's rule is traditionally regarded as the Pax Romana ("Roman Peace"). The cohesion of the empire was furthered by a degree of social stability and economic prosperity that Rome had never before experienced. Uprisings in the provinces were infrequent and put down "mercilessly and swiftly".[29] The success of Augustus in establishing principles of dynastic succession was limited by his outliving a number of talented potential heirs. The Julio-Claudian dynasty lasted for four more emperors—Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—before it yielded in 69 AD to the strife-torn Year of the Four Emperors, from which Vespasian emerged as victor. Vespasian became the founder of the brief Flavian dynasty, followed by the Nerva–Antonine dynasty which produced the "Five Good Emperors": Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius.[citation needed]

Transition from classical to late antiquity

In the view of contemporary Greek historian Cassius Dio, the accession of Commodus in 180 marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron",[30] a comment which has led some historians, notably Edward Gibbon, to take Commodus' reign as the beginning of the Empire's decline.[31][32]

In 212, during the reign of Caracalla, Roman citizenship was granted to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. The Severan dynasty was tumultuous; an emperor's reign was ended routinely by his murder or execution and, following its collapse, the Empire was engulfed by the Crisis of the Third Century, a period of invasions, civil strife, economic disorder, and plague.[33] In defining historical epochs, this crisis sometimes marks the transition from Classical to Late Antiquity. Aurelian (r. 270–275) stabilised the empire militarily and Diocletian reorganised and restored much of it in 285.[34] Diocletian's reign brought the empire's most concerted effort against the perceived threat of Christianity, the "Great Persecution".[citation needed]

Diocletian divided the empire into four regions, each ruled by a separate tetrarch.[35] Confident that he fixed the disorder plaguing Rome, he abdicated along with his co-emperor, but the Tetrarchy collapsed shortly after. Order was eventually restored by Constantine the Great, who became the first emperor to convert to Christianity, and who established Constantinople as the new capital of the Eastern Empire. During the decades of the Constantinian and Valentinian dynasties, the empire was divided along an east–west axis, with dual power centres in Constantinople and Rome. Julian, who under the influence of his adviser Mardonius attempted to restore Classical Roman and Hellenistic religion, only briefly interrupted the succession of Christian emperors. Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule over both East and West, died in 395 after making Christianity the state religion.[36]

Fall in the West and survival in the East

The Western Roman Empire began to disintegrate in the early 5th century. The Romans were successful in fighting off all invaders, most famously Attila,[37] but the empire had assimilated so many Germanic peoples of dubious loyalty to Rome that the empire started to dismember itself.[38] Most chronologies place the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476, when Romulus Augustulus was forced to abdicate to the Germanic warlord Odoacer.[39][40][41]

Odoacer ended the Western Empire by declaring Zeno sole emperor and placing himself as Zeno's nominal subordinate. In reality, Italy was ruled by Odoacer alone.[39][40][42] The Eastern Roman Empire, called the Byzantine Empire by later historians, continued until the reign of Constantine XI Palaiologos. The last Roman emperor died in battle in 1453 against Mehmed II and his Ottoman forces during the siege of Constantinople. Mehmed II adopted the title of caesar in an attempt to claim a connection to the Empire.[43]

Geography and demography

The Roman Empire was one of the largest in history, with contiguous territories throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.[44] The Latin phrase imperium sine fine ("empire without end"[45]) expressed the ideology that neither time nor space limited the Empire. In Virgil's Aeneid, limitless empire is said to be granted to the Romans by Jupiter.[46] This claim of universal dominion was renewed when the Empire came under Christian rule in the 4th century.[g] In addition to annexing large regions, the Romans directly altered their geography, for example cutting down entire forests.[48]

Roman expansion was mostly accomplished under the Republic, though parts of northern Europe were conquered in the 1st century, when Roman control in Europe, Africa, and Asia was strengthened. Under Augustus, a "global map of the known world" was displayed for the first time in public at Rome, coinciding with the creation of the most comprehensive political geography that survives from antiquity, the Geography of Strabo.[49] When Augustus died, the account of his achievements (Res Gestae) prominently featured the geographical cataloguing of the Empire.[50] Geography alongside meticulous written records were central concerns of Roman Imperial administration.[51]

The Empire reached its largest expanse under Trajan (r. 98–117),[52] encompassing 5 million square kilometres.[15][16] The traditional population estimate of 55–60 million inhabitants[53] accounted for between one-sixth and one-fourth of the world's total population[54] and made it the most populous unified political entity in the West until the mid-19th century.[55] Recent demographic studies have argued for a population peak from 70 million to more than 100 million.[56] Each of the three largest cities in the Empire – Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch – was almost twice the size of any European city at the beginning of the 17th century.[57]

As the historian Christopher Kelly described it:

Then the empire stretched from Hadrian's Wall in drizzle-soaked northern England to the sun-baked banks of the Euphrates in Syria; from the great Rhine–Danube river system, which snaked across the fertile, flat lands of Europe from the Low Countries to the Black Sea, to the rich plains of the North African coast and the luxuriant gash of the Nile Valley in Egypt. The empire completely circled the Mediterranean ... referred to by its conquerors as mare nostrum—'our sea'.[53]

Trajan's successor Hadrian adopted a policy of maintaining rather than expanding the empire. Borders (fines) were marked, and the frontiers (limites) patrolled.[52] The most heavily fortified borders were the most unstable.[24] Hadrian's Wall, which separated the Roman world from what was perceived as an ever-present barbarian threat, is the primary surviving monument of this effort.[58]

Languages

Latin and Greek were the main languages of the Empire,[h] but the Empire was deliberately multilingual.[63] Andrew Wallace-Hadrill says "The main desire of the Roman government was to make itself understood".[64] At the start of the Empire, knowledge of Greek was useful to pass as educated nobility and knowledge of Latin was useful for a career in the military, government, or law.[65] Bilingual inscriptions indicate the everyday interpenetration of the two languages.[66]

Latin and Greek's mutual linguistic and cultural influence is a complex topic.[67] Latin words incorporated into Greek were very common by the early imperial era, especially for military, administration, and trade and commerce matters.[68] Greek grammar, literature, poetry and philosophy shaped Latin language and culture.[69][70]

There was never a legal requirement for Latin in the Empire, but it represented a certain status.[72] High standards of Latin, Latinitas, started with the advent of Latin literature.[73] Due to the flexible language policy of the Empire, a natural competition of language emerged that spurred Latinitas, to defend Latin against the stronger cultural influence of Greek.[74] Over time Latin usage was used to project power and a higher social class.[75][76] Most of the emperors were bilingual but had a preference for Latin in the public sphere for political reasons, a "rule" that first started during the Punic Wars.[77] Different emperors up until Justinian would attempt to require the use of Latin in various sections of the administration but there is no evidence that a linguistic imperialism existed during the early Empire.[78]

After all freeborn inhabitants were universally enfranchised in 212, many Roman citizens would have lacked a knowledge of Latin.[79] The wide use of Koine Greek was what enabled the spread of Christianity and reflects its role as the lingua franca of the Mediterranean during the time of the Empire.[80] Following Diocletian's reforms in the 3rd century CE, there was a decline in the knowledge of Greek in the west.[81] Spoken Latin later fragmented into the incipient romance languages in the 7th century CE following the collapse of the Empire's west.[82]

The dominance of Latin and Greek among the literate elite obscure the continuity of other spoken languages within the Empire.[83] Latin, referred to in its spoken form as Vulgar Latin, gradually replaced Celtic and Italic languages.[84][85] References to interpreters indicate the continuing use of local languages, particularly in Egypt with Coptic, and in military settings along the Rhine and Danube. Roman jurists also show a concern for local languages such as Punic, Gaulish, and Aramaic in assuring the correct understanding of laws and oaths.[86] In Africa, Libyco-Berber and Punic were used in inscriptions into the 2nd century.[83] In Syria, Palmyrene soldiers used their dialect of Aramaic for inscriptions, an exception to the rule that Latin was the language of the military.[87] The last reference to Gaulish was between 560 and 575.[88][89] The emergent Gallo-Romance languages would then be shaped by Gaulish.[90] Proto-Basque or Aquitanian evolved with Latin loan words to modern Basque.[91] The Thracian language, as were several now-extinct languages in Anatolia, are attested in Imperial-era inscriptions.[80][83]

Society

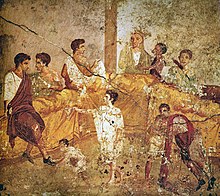

The Empire was remarkably multicultural, with "astonishing cohesive capacity" to create shared identity while encompassing diverse peoples.[93] Public monuments and communal spaces open to all—such as forums, amphitheatres, racetracks and baths—helped foster a sense of "Romanness".[94]

Roman society had multiple, overlapping social hierarchies.[95] The civil war preceding Augustus caused upheaval,[96] but did not effect an immediate redistribution of wealth and social power. From the perspective of the lower classes, a peak was merely added to the social pyramid.[97] Personal relationships—patronage, friendship (amicitia), family, marriage—continued to influence politics.[98] By the time of Nero, however, it was not unusual to find a former slave who was richer than a freeborn citizen, or an equestrian who exercised greater power than a senator.[99]

The blurring of the Republic's more rigid hierarchies led to increased social mobility,[100] both upward and downward, to a greater extent than all other well-documented ancient societies.[101] Women, freedmen, and slaves had opportunities to profit and exercise influence in ways previously less available to them.[102] Social life, particularly for those whose personal resources were limited, was further fostered by a proliferation of voluntary associations and confraternities (collegia and sodalitates): professional and trade guilds, veterans' groups, religious sodalities, drinking and dining clubs,[103] performing troupes,[104] and burial societies.[105]

Legal status

According to the jurist Gaius, the essential distinction in the Roman "law of persons" was that all humans were either free (liberi) or slaves (servi).[106] The legal status of free persons was further defined by their citizenship. Most citizens held limited rights (such as the ius Latinum, "Latin right"), but were entitled to legal protections and privileges not enjoyed by non-citizens. Free people not considered citizens, but living within the Roman world, were peregrini, non-Romans.[107] In 212, the Constitutio Antoniniana extended citizenship to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. This legal egalitarianism required a far-reaching revision of existing laws that distinguished between citizens and non-citizens.[108]

Women in Roman law

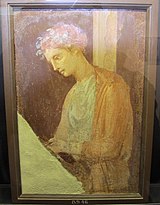

Right: Bronze statuette (1st century AD) of a young woman reading, based on a Hellenistic original

Freeborn Roman women were considered citizens, but did not vote, hold political office, or serve in the military. A mother's citizen status determined that of her children, as indicated by the phrase ex duobus civibus Romanis natos ("children born of two Roman citizens").[i] A Roman woman kept her own family name (nomen) for life. Children most often took the father's name, with some exceptions.[111] Women could own property, enter contracts, and engage in business.[112] Inscriptions throughout the Empire honour women as benefactors in funding public works, an indication they could hold considerable fortunes.[113]

The archaic manus marriage in which the woman was subject to her husband's authority was largely abandoned by the Imperial era, and a married woman retained ownership of any property she brought into the marriage. Technically she remained under her father's legal authority, even though she moved into her husband's home, but when her father died she became legally emancipated.[114] This arrangement was a factor in the degree of independence Roman women enjoyed compared to many other cultures up to the modern period:[115] although she had to answer to her father in legal matters, she was free of his direct scrutiny in daily life,[116] and her husband had no legal power over her.[117] Although it was a point of pride to be a "one-man woman" (univira) who had married only once, there was little stigma attached to divorce, nor to speedy remarriage after being widowed or divorced.[118] Girls had equal inheritance rights with boys if their father died without leaving a will.[119] A mother's right to own and dispose of property, including setting the terms of her will, gave her enormous influence over her sons into adulthood.[120]

As part of the Augustan programme to restore traditional morality and social order, moral legislation attempted to regulate conduct as a means of promoting "family values". Adultery was criminalized,[121] and defined broadly as an illicit sex act (stuprum) between a male citizen and a married woman, or between a married woman and any man other than her husband. That is, a double standard was in place: a married woman could have sex only with her husband, but a married man did not commit adultery if he had sex with a prostitute or person of marginalized status.[122] Childbearing was encouraged: a woman who had given birth to three children was granted symbolic honours and greater legal freedom (the ius trium liberorum).[123]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Roman_EmpireText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk