A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The relationship between science and the Catholic Church is a widely debated subject. Historically, the Catholic Church has been a patron of sciences. It has been prolific in the foundation and funding of schools, universities, and hospitals, and many clergy have been active in the sciences. Some historians of science such as Pierre Duhem credit medieval Catholic mathematicians and philosophers such as John Buridan, Nicole Oresme, and Roger Bacon as the founders of modern science.[1] Duhem found "the mechanics and physics, of which modern times are justifiably proud, to proceed by an uninterrupted series of scarcely perceptible improvements from doctrines professed in the heart of the medieval schools."[2] Historian John Heilbron says that "The Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment, than any other, and probably all, other Institutions."[3] The conflict thesis and other critiques emphasize the historical or contemporary conflict between the Catholic Church and science, citing, in particular, the trial of Galileo as evidence. For its part, the Catholic Church teaches that science and the Christian faith are complementary, as can be seen from the Catechism of the Catholic Church which states in regards to faith and science:

Though faith is above reason, there can never be any real discrepancy between faith and reason. Since the same God who reveals mysteries and infuses faith has bestowed the light of reason on the human mind, God cannot deny himself, nor can truth ever contradict truth. ... Consequently, methodical research in all branches of knowledge, provided it is carried out in a truly scientific manner and does not override moral laws, can never conflict with the faith, because the things of the world and the things of faith derive from the same God. The humble and persevering investigator of the secrets of nature is being led, as it were, by the hand of God despite himself, for it is God, the conserver of all things, who made them what they are.[4]

Catholic scientists, both religious and lay, have led scientific discovery in many fields.[5] From ancient times, Christian emphasis on practical charity gave rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals and the Church remains the single largest private provider of medical care and research facilities in the world.[6] Following the Fall of Rome, monasteries and convents remained bastions of scholarship in Western Europe and clergymen were the leading scholars of the age – studying nature, mathematics, and the motion of the stars (largely for religious purposes).[7] During the Middle Ages, the Church founded Europe's first universities, producing scholars like Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Roger Bacon, and Thomas Aquinas, who helped establish the scientific method.[8]

Today almost all historians agree that Christianity (Catholicism as well Protestantism) moved many early-modem intellectuals to study nature systematically. Historians have also found that notions borrowed from Christian bellef found their ways into scientific discourse, with glorious results.

— Noah J. Efron[9]

During this period, the Church was also a major patron of engineering for the construction of elaborate cathedrals. Since the Renaissance, Catholic scientists have been credited as fathers of a diverse range of scientific fields: Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) pioneered heliocentrism, René Descartes (1596-1650) father of analytical geometry and co-founder of modern philosophy, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) prefigured the theory of evolution with Lamarckism, Friar Gregor Mendel (1822-1884) pioneered genetics, and Fr Georges Lemaître (1894-1966) proposed the Big Bang cosmological model.[10] The Society of Jesus has been particularly active, notably in astronomy; the Papacy and the Jesuits initially promoted the observations and studies of Galileo Galilei, until the latter was put on trial and forced to recant by the Roman inquisition. Church patronage of sciences continues through institutions like the Pontifical Academy of Sciences (a successor to the Accademia dei Lincei of 1603) and Vatican Observatory (a successor to the Gregorian Observatory of 1580).[11]

According to historian John L. Heilbron, "Between 1650 and 1750, four Catholic churches were home to the best solar observatories in the world. Built to fix an unquestionable date for Easter, they also housed instruments that threw light on the disputed geometry of the solar system."[12]

The theory of conflict between science and the Church

This view of the Church as a patron of sciences is contested by some, who speak either of a historically varied relationship which has shifted, from active and even singular support to bitter clashes (with accusations of heresy) – or of an enduring intellectual conflict between religion and science.[13] Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire were famously dismissive of the achievements of the Middle Ages. In the 19th century, the "conflict thesis" emerged to propose an intrinsic conflict or conflicts between the Church and science. The original historical usage of the term asserted that the Church has been in perpetual opposition to science. Later uses of the term denote the Church's epistemological opposition to science. The thesis interprets the relationship between the Church and science as inevitably leading to public hostility when religion aggressively challenges new scientific ideas as in the Galileo Affair.[14] An alternative criticism is that the Church opposed particular scientific discoveries that it felt challenged its authority and power – particularly through the Reformation and on through the Enlightenment. This thesis shifts the emphasis away from the perception of the fundamental incompatibility of religion per se and science-in-general to a critique of the structural reasons for the resistance of the Church as a political organization.[15]

The Church itself rejects the notion of innate conflict. The Vatican Council (1869/70) declared that "Faith and reason are of mutual help to each other."[16] The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1912 proffers that "The conflicts between science and the Church are not real", and states that belief in such conflicts are predicated on false assumptions.[17] Pope John Paul II summarised the Catholic view of the relationship between faith and reason in the encyclical Fides et Ratio, saying that "faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth – in a word, to know himself – so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to the fullness of truth about themselves."[18] The present Papal astronomer Brother Guy Consolmagno describes science as an "act of worship" and as "a way of getting intimate with the Creator."[19]

Some leading Catholic scientists

Scientific fields with important foundational contributions from Catholic scientists include: physics (Galileo) despite his trial and conviction in 1633 for publishing a treatise on his observation that the earth revolves around the sun, which banned his writings and made him spend the remainder of his life under house arrest, acoustics (Mersenne), mineralogy (Agricola), modern chemistry (Lavoisier), modern anatomy (Vesalius), stratigraphy (Steno), bacteriology (Kircher and Pasteur), genetics (Mendel), analytical geometry (Descartes), heliocentric cosmology (Copernicus), atomic theory (Boscovich), and the Big Bang Theory on the origins of the universe (Lemaître). Jesuits devised modern lunar nomenclature and stellar classification and some 35 craters of the moon are named after Jesuits, among whose great scientific polymaths were Francesco Grimaldi and Giambattista Riccioli. The Jesuits also introduced Western science to India and China and translated local texts to be sent to Europe for study. Missionaries contributed significantly to the fields of anthropology, zoology, and botany during Europe's Age of Discovery.[citation needed]

Definitions of science

Differing analyses of the Catholic relationship to science may arise from definitional variance. While secular philosophers consider "science" in the restricted sense of natural science, in the past theologians tended to view science in a very broad sense as given by Aristotle's definition that science is the sure and evident knowledge obtained from demonstrations.[20] In this sense, science comprises the entire curriculum of university studies, and the Church has claimed authority in matters of doctrine and teaching of science. With the gradual secularisation of the West, the influence of the Church over scientific research has faded.[21]

History

Early Middle Ages

After the Fall of Rome, while an increasingly Hellenized Roman Empire and Christian religion endured as the Byzantine Empire in the East, the study of nature endured in monastic communities in the West. On the fringes of western Europe, where the Roman tradition had not made a strong imprint, monks engaged in the study of Latin as a foreign language, and actively investigated the traditions of Roman learning. Ireland's most learned monks even retained knowledge of Greek. Irish missionaries like Colombanus later founded monasteries in continental Europe, which went on to create libraries and become centers of scholarship.[22]

The leading scholars of the Early Middle Ages were clergymen, for whom the study of nature was but a small part of their scholarly interest. They lived in an atmosphere which provided opportunity and motives for the study of aspects of nature. Some of this study was carried out for explicitly religious reasons. The need for monks to determine the proper time to pray led them to study the motion of the stars;[23] the need to compute the date of Easter led them to study and teach rudimentary mathematics and the motions of the Sun and Moon.[24] Modern readers may find it disconcerting that sometimes the same works discuss both the technical details of natural phenomena and their symbolic significance.[25] In astronomical observation, Bede of Jarrow described two comets over England, and wrote that the "fiery torches" of AD 729 struck terror in all who saw them – for comets were heralds of bad news.[26]

Among these clerical scholars was Bishop Isidore of Seville who wrote a comprehensive encyclopedia of natural knowledge, the monk Bede of Jarrow who wrote treatises on The Reckoning of Time and The Nature of Things, Alcuin of York, abbot of the Abbey of Marmoutier, who advised Charlemagne on scientific matters, and Rabanus Maurus, Archbishop of Mainz and one of the most prominent teachers of the Carolingian Age, who, Like Bede, wrote treatises on computus and On the Nature of Things. Abbot Ælfric of Eynsham, who is known mostly for his Old English homilies, wrote a book on the astronomical time reckoning in Old English based on the writings of Bede. Abbo of Fleury wrote astronomical discussions of timekeeping and of the celestial spheres for his students, teaching for a while in England where he influenced the work of Byrhtferth of Ramsey, who wrote a Manual in Old English to discuss timekeeping and the natural and mystical significance of numbers.[27]

Later Middle Ages

Foundation of universities

In the early Middle Ages, Cathedral schools developed as centers of education, evolving into the medieval universities which were the springboard of many of Western Europe's later achievements.[28] During the High Middle Ages, Chartres Cathedral operated the famous and influential Chartres Cathedral School. Among the great early Catholic universities were Bologna University (1088);[29] Paris University (c 1150); Oxford University (1167);[30] Salerno University (1173); University of Vicenza (1204);[disputed – discuss] Cambridge University (1209); Salamanca University (1218-1219); Padua University (1222); Naples University (1224); and Vercelli University (1228).[31]

Using church Latin as a lingua franca, the medieval universities across Western Europe produced a great variety of scholars and natural philosophers, including Robert Grosseteste of the University of Oxford, an early expositor of a systematic method of scientific experimentation,[32] and Saint Albert the Great, a pioneer of biological field research.[33] By the mid-15th century, prior to the Reformation, Catholic Europe had some 50 universities.[31]

Condemnations of 1210-1277

The Condemnations of 1210-1277 were enacted at the medieval University of Paris to restrict certain teachings as being heretical. These included a number of medieval theological teachings, but most importantly the physical treatises of Aristotle. The investigations of these teachings were conducted by the Bishops of Paris. The Condemnations of 1277 are traditionally linked to an investigation requested by Pope John XXI, although whether he actually supported drawing up a list of condemnations is unclear.

Approximately sixteen lists of censured theses were issued by the University of Paris during the 13th and 14th centuries.[34] Most of these lists of propositions were put together into systematic collections of prohibited articles.[34]

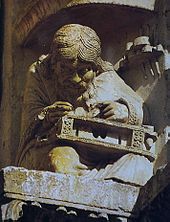

Mathematics, engineering and architecture

According to art historian Kenneth Clark, "to medieval man, geometry was a divine activity. God was the great geometer, and this concept inspired the architect."[35] Monumental cathedrals such as that of Chartres appear to evidence a complex understanding of mathematics.[35] The Church has invested greatly in engineering and architecture and founded a number of architectural genres – including Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, High Renaissance, and Baroque.[31]

Roman Inquisition

In the Middle Ages of the Roman Church, Pope Paul III (1468-1549) initiated the Congregation of the Roman Inquisition in 1542,[36] which is also known as the Holy Office.[37] A large expansion of Protestantism began to spread all throughout Italy, which triggered Pope Paul III to act against it. He would be the first to create proactive reforms for the sake of Roman Catholicism.[38] Evidently the reforms would be strict rulings against foreign ideologies that would fall outside of their religious beliefs. The Inquisition would soon be under the control of Pope Sixtus V in 1588.

View of outsiders

The Roman society was not very fond of outside beliefs. They would keep their borders up to religious foreigners as they felt other practices would influence and change their sacred Catholicism religion.[39] They were also against witchcraft as such practices were seen in 1484 where Pope Innocent stated it was an act of going against the church.[40] Any ideologies that was outside of their norm beliefs was seen as a threat and needed to be corrected even if it was through torture.

Inquisition tactics and practices

Pope Sixtus V put forth 15 congregations. The inquisition would imprison anyone who was seen as a threat towards the Catholic Church or placed onto house arrest.[41] They kept a tight security and denied any other religious foreigners from coming inside their regions. Papal policies were implemented to stop foreigners from showing their practices to the public. The Index of Forbidden Books was used to prevent people from doing magic[42] and to suppress books deemed heretical, politically disruptive, or threatening to public morals. To stray away from this would allow for one to not be "infected".[43] Punishment was acceptable and torture tactics were used in order for one to confess their sins.[44]

The fall of the inquisition

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Science_and_the_Catholic_ChurchText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk