A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

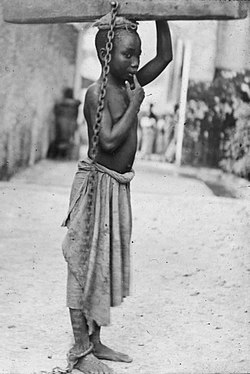

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate slaves around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. Under the actions of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, chattel slavery has been abolished across Japan since 1590, though other forms of forced labour were used during World War II. The first and only country to self-liberate from slavery was actually a former French colony, Haiti, as a result of the Revolution of 1791–1804. The British abolitionist movement began in the late 18th century, and the 1772 Somersett case established that slavery did not exist in English law. In 1807, the slave trade was made illegal throughout the British Empire, though existing slaves in British colonies were not liberated until the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. Vermont was the first state in America to abolish slavery in 1777. By 1804, the rest of the northern states had abolished slavery but it remained legal in southern states. By 1808, the United States outlawed the importation of slaves but did not ban slavery outright until 1865.

In Eastern Europe, groups organized to abolish the enslavement of the Roma in Wallachia and Moldavia between 1843 and 1855, and to emancipate the serfs in Russia in 1861. The United States would pass the 13th Amendment in December 1865 after having just fought a bloody Civil War, ending slavery "except as a punishment for crime". In 1888, Brazil became the last country in the Americas to outlaw slavery. As the Empire of Japan annexed Asian countries, from the late 19th century onwards, archaic institutions including slavery were abolished in those countries.

After centuries of struggle, slavery was eventually declared illegal at the global level in 1948 under the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Mauritania was the last country to officially abolish slavery, with a presidential decree in 1981.[1] Today, child and adult slavery and forced labour are illegal in almost all countries, as well as being against international law, but human trafficking for labour and for sexual bondage continues to affect tens of millions of adults and children.

France

Early abolition in metropolitan France

Balthild of Chelles, herself a former slave, queen consort of Neustria and Burgundy by marriage to Clovis II, became regent in 657 since the king, her son Chlothar III, was only five years old. At some unknown date during her rule, she abolished the trade of slaves, although not slavery. Moreover, her (and contemporaneous Saint Eligius') favorite charity was to buy and free slaves, especially children. Slavery started to dwindle and would be superseded by serfdom.[2][3]

In 1315, Louis X, king of France, published a decree proclaiming that "France signifies freedom" and that any slave setting foot on French soil should be freed. This prompted subsequent governments to circumscribe slavery in the overseas colonies.[4]

Some cases of African slaves freed by setting foot on French soil were recorded such as the example of a Norman slave merchant who tried to sell slaves in Bordeaux in 1571. He was arrested and his slaves were freed according to a declaration of the Parlement of Guyenne which stated that slavery was intolerable in France, although it is a misconception that there were 'no slaves in France'; thousands of African slaves were present in France during the 18th century.[5][6] Born into slavery in Saint Domingue, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas became free when his father brought him to France in 1776.

Code Noir and Age of Enlightenment

As in other New World colonies, the French relied on the Atlantic slave trade for labour for their sugar cane plantations in their Caribbean colonies; the French West Indies. In addition, French colonists in Louisiane in North America held slaves, particularly in the South around New Orleans, where they established sugarcane plantations.

Louis XIV's Code Noir regulated the slave trade and institution in the colonies. It gave unparalleled rights to slaves. It included the right to marry, gather publicly or take Sundays off. Although the Code Noir authorized and codified cruel corporal punishment against slaves under certain conditions, it forbade slave owners to torture them or to separate families. It also demanded enslaved Africans receive instruction in the Catholic faith, implying that Africans were human beings endowed with a soul, a fact French law did not admit until then. It resulted in a far higher percentage of Black people being free in 1830 (13.2% in Louisiana compared to 0.8% in Mississippi).[7] They were on average exceptionally literate, with a significant number of them owning businesses, properties, and even slaves.[8][9] Other free people of colour, such as Julien Raimond, spoke out against slavery.

The Code Noir also forbade interracial marriages, but it was often ignored in French colonial society and the mulattoes became an intermediate caste between whites and blacks, while in the British colonies mulattoes and blacks were considered equal and discriminated against equally.[9][10]

During the Age of Enlightenment, many philosophers wrote pamphlets against slavery and its moral and economical justifications, including Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws (1748) and Denis Diderot in the Encyclopédie.[11] In 1788, Jacques Pierre Brissot founded the Society of the Friends of the Blacks (Société des Amis des Noirs) to work for the abolition of slavery. After the Revolution, on 4 April 1792, France granted free people of colour full citizenship.

The slave revolt, in the largest Caribbean French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1791, was the beginning of what became the Haitian Revolution led by formerly enslaved people like Georges Biassou, Toussaint L'Ouverture, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. The rebellion swept through the north of the colony, and with it came freedom to thousands of enslaved blacks, but also violence and death.[12] In 1793, French Civil Commissioners in St. Domingue and abolitionists, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel, issued the first emancipation proclamation of the modern world (Decree of 16 Pluviôse An II). The Convention sent them to safeguard the allegiance of the population to revolutionary France. The proclamation resulted in crucial military strategy as it gradually brought most of the black troops into the French fold and kept the colony under the French flag for most of the conflict.[13] The connection with France lasted until blacks and free people of colour formed L'armée indigène in 1802 to resist Napoleon's Expédition de Saint-Domingue. Victory over the French in the decisive Battle of Vertières finally led to independence and the creation of present Haiti in 1804.[14]

First general abolition of slavery (1794)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

The convention, the first elected Assembly of the First Republic (1792–1804), on 4 February 1794, under the leadership of Maximilien Robespierre, abolished slavery in law in France and its colonies.[15] Abbé Grégoire and the Society of the Friends of the Blacks were part of the abolitionist movement, which had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole. The first article of the law stated that "Slavery was abolished" in the French colonies, while the second article stated that "slave-owners would be indemnified" with financial compensation for the value of their slaves. The French constitution passed in 1795 included in the declaration of the Rights of Man that slavery was abolished.

Re-establishment of slavery in the colonies (1802)

During the French Revolutionary Wars, French slave-owners joined the counter-revolution en masse and, through the Whitehall Accord, they threatened to move the French Caribbean colonies under British control, as Great Britain still allowed slavery. Fearing secession from these islands, successfully lobbied by planters and concerned about revenues from the West Indies, and influenced by the slaveholder family of his wife, Napoleon Bonaparte decided to re-establish slavery after becoming First Consul. He promulgated the law of 20 May 1802 and sent military governors and troops to the colonies to impose it.

On 10 May 1802, Colonel Delgrès launched a rebellion in Guadeloupe against Napoleon's representative, General Richepanse. The rebellion was repressed, and slavery was re-established.

Abolition of slavery in Haiti (1804)

The news of the Law of 4 February 1794 that abolished slavery in France and its colonies and the revolution led by Colonel Delgrès sparked another wave of rebellion in Saint-Domingue. From 1802 Napoleon sent more than 20,000 troops to the island, two-thirds died, mostly from yellow fever.

Seeing the failure of the Saint-Domingue expedition, in 1803 Napoleon decided to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States.

The French governments initially refused to recognize Haïti. It forced the nation to pay a substantial amount of reparations (which it could ill afford) for losses during the revolution and did not recognize its government until 1825.

France was a signatory to the first multilateral treaty for the suppression of the slave trade, the Treaty for the Suppression of the African Slave Trade (1841), but the king, Louis Philippe I, declined to ratify it.

Second abolition (1848) and subsequent events

On 27 April 1848, under the Second Republic (1848–1852), the decree-law written by Victor Schœlcher abolished slavery in the remaining colonies. The state bought the slaves from the colons (white colonists; Békés in Creole), and then freed them.

At about the same time, France started colonizing Africa and gained possession of much of West Africa by 1900. In 1905, the French abolished slavery in most of French West Africa. The French also attempted to abolish Tuareg slavery following the Kaocen Revolt. In the region of the Sahel, slavery has long persisted.

Passed on 10 May 2001, the Taubira law officially acknowledges slavery and the Atlantic slave trade as a crime against humanity. 10 May was chosen as the day dedicated to recognition of the crime of slavery.

Great Britain

Overview

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=AbolitionismText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk