A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| National and regional referendums held within the United Kingdom and its constituent countries | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum, also known as the UK-wide referendum on the Parliamentary voting system was held on Thursday 5 May 2011 in the United Kingdom to choose the method of electing MPs at subsequent general elections. It occurred as a provision of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement drawn up in 2010 (after a general election that had resulted in the first hung parliament since February 1974) and also indirectly in the aftermath of the 2009 expenses scandal. It operated under the provisions of the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 and was the first national referendum to be held under provisions laid out in the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. Many local elections were also held on this day.

The referendum concerned whether to replace the present "first-past-the-post" system with the "alternative vote" (AV) method and was the first national referendum to be held across the whole of the United Kingdom in the twenty-first century. The proposal to introduce AV was rejected by 67.9% of voters on a national turnout of 42%. The failure of the referendum was considered a humiliating setback for Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg, who had acquiesced to the Conservative offer of a referendum on AV rather than proportional representation (PR) as part of the coalition agreement.[1][2] The referendum was linked to the ongoing decline of his popularity and that of the Liberal Democrats in general.[3][4]

This was only the second UK-wide referendum to be held (the first was the EC referendum in 1975) and the first such to be overseen by the Electoral Commission. It is to date the only UK-wide referendum to be held on an issue not related to the European Communities or the European Union, and is also the first to have been not merely consultative: it committed the government to give effect to its decision.[5]

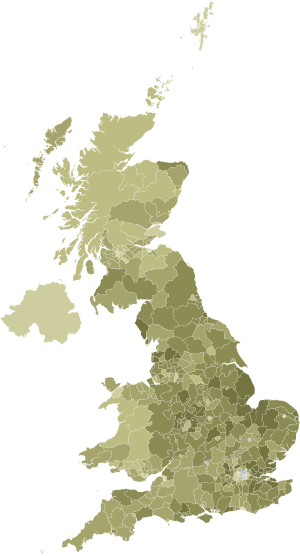

All registered electors over 18 (British, Irish and Commonwealth citizens living in the UK and enrolled British citizens living outside)[6] – including members of the House of Lords (who cannot vote in UK general elections) – were entitled to take part. On a turnout of 42.2 percent, 68 percent voted 'No' and 32 percent voted 'Yes'. Ten of the 440 local voting areas recorded 'Yes' votes above 50 per cent: four were Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh Central and Glasgow Kelvin, with the remaining six being in London.[7]

History

Historical context

The alternative vote and the single transferable vote (STV) for the House of Commons were debated in Parliament several times between 1917 and 1931, and came close to being adopted. Both the Liberals and Labour at various times supported a change from non-transferable voting to AV or STV in one-, two- and three-member constituencies. STV was adopted for the university seats (which were abolished in 1949).[8] Both AV and STV involve voters rank-ordering preferences. However, STV is considered to be a form of proportional representation, using multi-member constituencies, while AV, in single-member constituencies, is not.[9]

In 1950, all constituencies became single-member and all votes non-transferable.[10] From then until 2010, the Labour and Conservative parties, the two parties who formed each government of the United Kingdom normally by virtue of an overall majority in the Commons, always voted down proposals for moving away from this uniform "first-past-the-post" (FPTP) voting system for the Commons.[citation needed] Other voting systems were introduced for various other British elections. STV was reintroduced in Northern Ireland and list-PR introduced for European elections except in Northern Ireland.

Whilst out of power, the Labour Party set up a working group to examine electoral reform. The resulting Plant Commission reported in 1993 and recommended the adoption, for elections to the Commons, of the supplementary vote, the system used to elect the Mayor of London.[11] Labour's 1997 manifesto committed the party to a referendum on the voting system for the Commons and to setting up an independent commission to recommend a proportional alternative to FPTP to be put in that referendum.[12]

After winning the 1997 general election, the new Labour government consequently set up the Jenkins Commission into electoral reform, supported by the Liberal Democrats, the third party in British politics in recent years and long supporters of proportional representation. (The Commission chair, Roy Jenkins, was a Liberal Democrat peer and former Labour minister.) The commission reported in September 1998 and proposed the novel alternative vote top-up or AV+ system. Having been tasked to meet a "requirement for broad proportionality",[13] the Commission rejected both FPTP, as the status quo, and AV as options. It pointed out (chapter 3, para 21) that "the single-member constituency is not an inherent part of the British parliamentary tradition. It was unusual until 1885...Until most seats were two-member..." (referring to the English system established in 1276). Jenkins rejected AV because "so far from doing much to relieve disproportionality, it is capable of substantially adding to it".[14] AV was also described as "disturbingly unpredictable" and "unacceptably unfair".[15]

However, legislation for a referendum was not put forward. Proportional systems were introduced for the new Scottish Parliament and Welsh and London Assemblies, and the supplementary vote was introduced for mayoral elections. With House of Lords reform in 1999, AV was introduced to elect replacements for the remaining 92 hereditary peers who sit in the Lords.[16]

At the next general election in 2001, Labour's manifesto stated that the party would review the experience of the new systems (in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and the Jenkins report, to assess the possibility of changes to the Commons, which would still be subject to a referendum.[17] Electoral reform in the Commons remained at a standstill, although in the Scottish Parliament, a coalition of Labour and the Liberal Democrats introduced STV for local elections in Scotland.

Pre-election

In February 2010, the Labour government (which had been in power since 1997) used its majority to pass an amendment to its Constitutional Reform Bill to include a referendum on the introduction of AV to be held in the next Parliament, citing a desire to restore trust in Parliament in the wake of the 2009 expenses scandal.[18] A Liberal Democrat amendment to hold the referendum earlier, and on STV,[19] was defeated by 476 votes to 69.[18] There was insufficient time remaining in the term of that Parliament for the Bill to become law before Parliament was dissolved; and so the move was dismissed by several Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs as a political manoeuvre.[18]

In the ensuing 2010 general election campaign, the Labour manifesto supported the introduction of AV via a referendum, to "ensure that every MP is supported by the majority of their constituents voting at each election".[20] The Liberal Democrats argued for proportional representation, preferably by single transferable vote, and the Conservatives argued for the retention of FPTP. Both the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats proposed reducing the number of MPs, while the Conservative Party argued for more equal sized constituencies.

Election outcome to Queen's Speech

The 2010 UK general election held on 6 May resulted in a hung parliament, the first since 1974, leading to a period of negotiations. Honouring a pre-election pledge, the Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg entered into negotiations with the Conservatives as the party who had won most votes and most seats. William Hague offered the Liberal Democrats a referendum on the alternative vote as part of a "final offer" in the Conservatives' negotiations for a proposed "full and proper" coalition between the two parties.[21] Hague and Conservative leader David Cameron said that this was in response to Labour offering the Liberal Democrats the alternative vote without a referendum, although it later emerged that Labour had not made such an offer.[22] Negotiations between the Liberal Democrats and Labour quickly ended.[21] On 11 May 2010, Prime Minister Gordon Brown stepped down, followed by the establishment of a full coalition government between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. David Cameron became Prime Minister and Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg became Deputy Prime Minister.

The initial Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement, dated 11 May 2010, detailed the issues which had been agreed between the two parties before they committed to entering into coalition. On the issue of an electoral reform referendum, it stated:

The parties will bring forward a Referendum Bill on electoral reform, which includes provision for the introduction of the Alternative Vote in the event of a positive result in the referendum, as well as for the creation of fewer and more equal sized constituencies. Both parties will whip their Parliamentary Parties in both Houses to support a simple majority referendum on the Alternative Vote, without prejudice to the positions parties will take during such a referendum.[23]

Following the agreement between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, with the new coalition government now formed, a commitment to the referendum was included in the coalition government's Queen's Speech on 25 May 2010 as the Parliamentary Reform Bill, although with no date set for the referendum.[24]

The coalition agreement committed both parties in the government to "whip" their Parliamentary parties in both the House of Commons and House of Lords to support the bill, thereby ensuring that it could reasonably be expected to be passed into law due to the simple majority in the Commons of the combined Conservative – Liberal Democrat voting bloc. The Lords can only delay, rather than block, a Bill passed by the Commons.

Passage through Parliament

According to The Guardian, reporting after the Queen's Speech, unnamed pro-referendum Cabinet members were believed to want the referendum held on 5 May 2011, to coincide with elections to the Scottish parliament, the Welsh assembly and many English local councils. Nick Clegg's prior hope of a referendum as early as October 2010 was considered unrealistic due to the parliamentary programme announced in the speech.[25]

On 5 July 2010, Clegg announced the detailed plans for the Parliamentary Reform Bill in a statement to the House of Commons, as part of the wider package of voting and election reforms set out in the coalition agreement, including setting the referendum date as 5 May 2011.[26][27] In addition to a referendum on AV, the reform bill also included the other coalition measures of reducing and resizing the Westminster parliamentary constituencies, introducing fixed-term parliaments and setting the date of the next general election as 7 May 2015, changing the voting threshold for early dissolution of parliament to 55%, and providing for the recall of MPs by their constituents.[28]

The plans to hold the vote on 5 May faced criticism from some Conservative MPs as distorting the result because turnout was predicted to be higher in those places where local elections were also held. It also faced criticism from Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish MPs for the effects it would have on their devolved elections on the same day, while Clegg himself faced further criticism from Labour, and implied lessening support from Liberal Democrat MPs, for backing down on earlier Liberal Democrat positions on proportional representation.[1] Clegg defended the date, stating the referendum question was simple and that it would save £17m in costs.[29] Over 45 MPs, mostly Conservatives, signed a motion calling for the date to be moved.[30] In September 2010, Ian Davidson MP, chairman of the Commons Scottish affairs select committee, stated after consultation with the Scottish Parliament that there was "unanimous" opposition among Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) to the referendum date, following the "chaos" of the combined 2007 Scottish parliament and council elections.[31]

On 22 July 2010, the proposal for fixed-term parliaments was put before parliament as the Fixed-term Parliaments Bill, while the proposals for the AV referendum, change in dissolution arrangements and equalising constituencies were put forward in the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Bill, which accordingly had three parts: Part 1, Voting system for parliamentary elections; Part 2, Parliamentary constituencies; and Part 3, Miscellaneous and general.[32][33] The Bill contained the text of a proposed referendum question.[32]

The original proposed question in English was:[34]

Do you want the United Kingdom to adopt the "alternative vote" system instead of the current "first past the post" system for electing Members of Parliament to the House of Commons?

In Welsh:

Ydych chi am i'r Deyrnas Unedig fabwysiadu'r system "bleidlais amgen" yn lle'r system "first past the post" presennol ar gyfer ethol Aelodau Seneddol i Dŷ'r Cyffredin?

permitting a simple YES / NO answer (to be marked with a single (X)).

This wording was criticised by the Electoral Commission, saying that "particularly those with lower levels of education or literacy, found the question hard work and did not understand it". The Electoral Commission recommended a changed wording to make the issue easier to understand,[35] and the government subsequently amended the Bill to bring it into line with the Electoral Commission's recommendations.[36]

The Bill passed an interim vote in the Commons on 7 September 2010 by 328 votes to 269.[30]

An amendment proposed in the Lords by Lord Rooker (Independent) to require a minimum turn-out of 40% for the referendum to be valid was supported by Labour, a majority of cross-benchers and ten rebel Conservatives, and was passed by one vote.[37] Labour's 2010 AV referendum proposal had not included such a threshold and they were criticised for seeking to impose one for this referendum, while the 2011 Welsh referendum, held under a Bill passed by Labour, also had no threshold[38] (and would have failed if it had had one, as turnout in that referendum was only 35%). In the latter hours of debate, a "game" of parliamentary ping-pong saw the Commons overturning the threshold amendment before it was reimposed by the Lords, and then removed again.[39]

After some compromises between the two Houses on amendments, the Bill was passed into law on 16 February 2011.[39]

Legislation

The Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 provides for the holding of the referendum, and the related changes had it led to the adoption of AV. Passing the bill into law was a necessary measure before the referendum could actually take place. It received Royal assent on 16 February 2011.[39]

The Act has the following long title:[33]

An Act to make provision for a referendum on the voting system for parliamentary elections and to provide for parliamentary elections to be held under the alternative vote system if a majority of those voting in the referendum are in favour of that; to make provision about the number and size of parliamentary constituencies; and for connected purposes

Referendum question

Based on the coalition agreement, the referendum was a simple majority yes/no question as to whether to replace the current first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system used in general elections with the alternative vote (AV) system.

The question posed by the referendum was:[36]

At present, the UK uses the "first past the post" system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the "alternative vote" system be used instead?

In Wales, the question on the ballot paper also appeared in Welsh:

Ar hyn o bryd, mae'r DU yn defnyddio'r system "y cyntaf i’r felin" i ethol ASau i Dŷ'r Cyffredin. A ddylid defnyddio’r system "pleidlais amgen" yn lle hynny?

permitting a simple YES / NO answer (to be marked with a single (X)).

Administration

The referendum took place on 5 May 2011, coinciding with various United Kingdom local elections, the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, the 2011 Welsh Assembly election and the 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly election.[26] The deadline for voters in England, Wales and Northern Ireland to register to vote in the referendum was midnight on Thursday 14 April 2011, whilst voters in Scotland had until midnight on Friday 15 April 2011 to register. Anyone in the United Kingdom who qualified as an anonymous elector had until midnight on Tuesday 26 April 2011 to register.[40] In the vote count, the referendum ballots in England, Scotland and Wales were counted after the various election ballots, from 4 pm on 6 May 2011.[41] The referendum had no minimum threshold on the required turnout needed for the result to be valid.[39]

Anyone on the electoral register and eligible to vote in a general election was entitled to vote in the referendum.[6] This includes British citizens living outside the UK who were registered as overseas electors. In addition, Members of the House of Lords, who are not eligible to vote in a general election, were entitled to vote in the referendum, provided they were entitled to vote in local elections.

Campaign positions

Political parties

| Political parties' position on the referendum | For a 'Yes' vote (introduce AV) | No official party position | For a 'No' vote (oppose AV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parties elected to the House of Commons | Liberal Democrats Scottish National Party Sinn Féin Plaid Cymru Social Democratic and Labour Party Green Party of England and Wales Alliance Party of Northern Ireland |

Labour Party | Conservative Party Democratic Unionist Party |

| Parties elected to the European Parliament or regional assemblies / parliaments | UKIP Scottish Greens |

British National Party Ulster Unionist Party Green Party in Northern Ireland | |

| Minor parties | Liberal Party Mebyon Kernow English Democrats Christian Party Christian Peoples Alliance Pirate Party UK Libertarian Party |

Socialist Party of Great Britain Official Monster Raving Loony Party |

Traditional Unionist Voice Respect Party Communist Party of Britain Socialist Party Alliance for Workers' Liberty |

Coalition parties

The coalition partners campaigned on opposite sides, with the Liberal Democrats supporting AV and the Conservatives opposing it.[42]

Despite the Conservative Party's formal position, party members who were aligned to the Conservative Action for Electoral Reform, an internal party group in favour of electoral reform, campaigned in favour,[43] while a BBC News report described "some Tory MPs" as being "relaxed" about a 'Yes' result.[44] Some Conservatives campaigned in favour of AV, e.g. Andrew Boff AM;[45] and Andrew Marshall, former head of the Conservative Group on Camden Council.[46] The Conservative Party uses a system of successive ballots to elect its leader,[47] which has been described as a "form of AV" (since the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated in each round),[48] but unlike AV, the candidates are not ranked in order of preference during each ballot.

Other parties represented in the House of Commons

Labour elected a new leader following the 2010 general election and many of the leadership candidates supported AV, including winner Ed Miliband;[49][50] however, Andy Burnham was critical of the referendum.[51] Former Labour Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett was president of the No to AV campaign.[52] Other supporters of the party also used the referendum to attack the coalition[53] and voiced opposition to the bill currently providing for the referendum, on the grounds of the inclusion of boundary changes that are viewed as beneficial to the Conservative Party.[54]

Plaid Cymru supported AV, but did not take an active role in the campaign, as it focused on separate Welsh votes on the same day.[44] The Scottish National Party, while maintaining its longstanding support for PR-STV, also supported a 'Yes' vote in the referendum.[44] Both of these parties opposed the planned referendum date, as they did not want it held at the same time as the 2011 Welsh Assembly elections and the 2011 Scottish Parliament elections respectively.[30]

Among the Northern Irish parties, the Alliance Party and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) supported AV.[55] SDLP leader Margaret Ritchie announced that her party would actively campaign in favour.[56] Sinn Féin also supported a 'Yes' vote, but the Democratic Unionist Party supported a 'No' vote.[57]

The Green Party of England and Wales voted in favour of joining the campaign for AV in the referendum at its September 2010 party conference. Many leading figures in the party supported the change as a step towards their preferred system, proportional representation.[58] Previously, the party's leader and only MP, Caroline Lucas, had called for a referendum that included a choice of proportional representation.[59] However, at the party's Conference, Deputy Leader Adrian Ramsay argued that "If you vote No in this referendum, nobody would know whether you were rejecting AV because you wanted genuine reform, or were simply opposing any reform."[58]

Minor parties

The UK Independence Party's National Executive Committee formally announced that it would be supporting Alternative Vote, although it would prefer a proportional system.[60] An e-mail was sent to members informing them that they might vote against AV, but were not allowed to campaign.[44][61]

The British National Party criticised AV[62] and supported a 'No' vote.[44]

The Respect Party also supported proportional representation and campaigned against AV.[44] Rob Hoveman, on behalf of Tower Hamlets Respect, wrote to the East London Advertiser on 24 February 2011 urging a 'No' vote on the grounds that the AV system created an even greater imbalance between votes and seats, and urging a proportional system instead.[63]

The Scottish Green Party also supported AV, although it prefers the adoption of STV for all elections.[44][64]

The Ulster Unionist Party and Traditional Unionist Voice supported a 'No' vote.[57] The Green Party Northern Ireland also opposed the change to AV, as they viewed it as a betrayal of proportional representation.[65]

The English Democrats,[44] the Christian Peoples Alliance[44] and the Christian Party all supported AV.[66] Pirate Party UK endorsed a 'Yes' vote, with over 90% of members expressing support for AV.[67]

The Liberal Party agreed to support the 'Yes' campaign, seeing AV as "a potential 'stepping stone' to further reform" and STV.[68]

The Communist Party of Britain opposed AV.[44]

Mebyon Kernow, the Cornish nationalist party, favoured proportional representation and was disappointed that the referendum did not give voters that option.[69] However, leader Dick Cole announced on 1 April 2011 that Mebyon Kernow would be supporting the 'Yes' campaign.[70]

The United Kingdom Libertarian Party favoured AV[71] as a slight improvement on first-past-the-post.

The Socialist Party of Great Britain adopted a neutral position, arguing "what matters more is what we use our votes for" in the context of class struggle.[72]

The Socialist Party opposed AV, pointing out that it is not more proportional than First Past the Post.[73]

The Alliance for Workers' Liberty opposed AV, arguing that it did not offer progress on the party's main democratic demands.[74]

Politicians

Prime Minister David Cameron of the Conservative Party and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg of the Liberal Democrats made speeches backing the 'No' and 'Yes' campaigns respectively on the same day, but were thereafter not expected to take much part in the campaigns,[75] although both were active since. Cameron described AV as "undemocratic, obscure, unfair and crazy".[76] He was praised for his intervention by back-bench Conservative MPs.[77]

Labour leader Ed Miliband said he would take an active part in the 'Yes' campaign,[78] while Wales's First Minister and Welsh Labour Leader Carwyn Jones[79] and Scottish Labour Leader Iain Gray both also supported AV.[80] Also supporting the 'Yes' campaign were over 50 Labour MPs including Alan Johnson, Peter Hain, Hilary Benn, John Denham, Liam Byrne, Sadiq Khan, Tessa Jowell, Ben Bradshaw, Douglas Alexander,[81] Alistair Darling,[82] Diane Abbott and Debbie Abrahams.[83] Labour peers supporting the 'Yes' campaign include Lord Mandelson, Oona King, Raymond Plant (chair of Labour's 1993 working group on electoral reform), Andrew Adonis, Anthony Giddens, former Labour leader Neil Kinnock, former deputy leader Roy Hattersley and Glenys Kinnock,[84] while further Labour figures supporting AV included former Mayor of London Ken Livingstone,[83] Michael Cashman MEP, Tony Benn,[85] and former Labour council candidate and wife of the Speaker Sally Bercow.[86]

The Liberal Democrats supported a 'Yes' vote and many individual Liberal Democrat politicians were active in the 'Yes' campaign. The SNP leader, Alex Salmond, supported a 'Yes' vote.[80] UKIP supported a 'Yes' vote and their principal spokesmen on the campaign were William Dartmouth MEP and party leader, Nigel Farage MEP.[60]

Supporting the 'No' campaign were both senior Conservative (including William Hague, Kenneth Clarke, George Osborne, Theresa May, Philip Hammond, Steven Norris and Baroness Warsi)[87] and Labour politicians (including John Prescott, Margaret Beckett (president of the No to AV campaign), David Blunkett, John Reid, Tony Lloyd, John Healey, Caroline Flint, Hazel Blears, Beverley Hughes, Paul Boateng, John Hutton and Lord Falconer).[52] The Conservative Party announced that seven MPs (Conor Burns, George Eustice, Sam Gyimah, Kwasi Kwarteng, Charlotte Leslie, Priti Patel, Chris Skidmore) and two former candidates (Chris Philp and Maggie Throup, later elected as MPs) would act as party spokespersons in the 'No' campaign.[88] Overall, most Labour MPs supported the 'No' campaign rather than the 'Yes' campaign, with other notable opponents of AV including Paul Goggins, Ann Clwyd, Sir Gerald Kaufman, Austin Mitchell, Margaret Hodge, Lindsay Hoyle, Jim Fitzpatrick, Dennis Skinner and Keith Vaz.[82] Also supporting a 'No' vote were crossbencher and former SDP leader Lord Owen, who supported the No to AV But Yes to PR campaign.[89]

Conservative politician Michael Gove was initially mistakenly announced by the No to AV campaign as opposing AV, but his advisers stated that he had never been involved in the campaign and had not yet made up his mind.[90] Over five Labour MPs announced as opposing AV were also found to have been wrongly included:[91][92] for example, Alun Michael supported a 'Yes' vote,[91] while Meg Hillier did not lend her name to either campaign.[93]

Some Conservative politicians did support AV, including John Strafford, a former member of the Conservative Party's national executive, who chaired the Conservative campaign in favour of a 'Yes' vote.[94]

Other organisations

AV campaigning organisations

Two campaign groups were established in response to the proposed referendum, one on each side of the debate. NOtoAV was established to campaign against the change to the alternative vote[95] and YES! To Fairer Votes[96] was established to campaign in favour.[97]

Political reform groups

Take Back Parliament,[98] the Electoral Reform Society,[99] Make My Vote Count,[100] and Unlock Democracy[101] all campaigned in favour of the change to AV.

Trade unions

The GMB Union opposes the change to AV. It provided "substantial" sums of money to the 'No' campaign and marshalled its members to vote 'No'.[102] Unions generally supported the 'No' campaign, with only Billy Hayes, general secretary of the Communication Workers' Union, supporting AV.[103]

Think tanks

Compass supported the change to the AV and urged the Labour Party to do so too.[50][104] It prefers a switch to a more proportional system, but viewed AV as superior to FPTP. ResPublica supported the change to AV and urged the Conservative Party to do so too.[105] Policy Exchange opposed the change to AV.[106] Ekklesia supported the change to AV.[107]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=2011_United_Kingdom_Alternative_Vote_referendum

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk