A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Egyptian | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

Ebers Papyrus detailing treatment of asthma | |||||||

| Region | Originally, throughout Ancient Egypt and parts of Nubia (especially during the times of the Nubian kingdoms)[2] | ||||||

| Ethnicity | Ancient Egyptians | ||||||

| Era | Late fourth millennium BC – 19th century AD[note 2] (with the extinction of Coptic); still used as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox and Coptic Catholic Churches | ||||||

Afro-Asiatic

| |||||||

| Dialects |

| ||||||

| Hieroglyphs, cursive hieroglyphs, Hieratic, Demotic and Coptic (later, occasionally, Arabic script in government translations and Latin script in scholars' transliterations and several hieroglyphic dictionaries[5]) | |||||||

| Language codes | |||||||

| ISO 639-2 | egy (also cop for Coptic) | ||||||

| ISO 639-3 | egy (also cop for Coptic) | ||||||

| Glottolog | egyp1246 | ||||||

| Linguasphere | 11-AAA-a | ||||||

The Egyptian language or Ancient Egyptian (r n km.t)[1][6] is an extinct branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts, which were made accessible to the modern world following the decipherment of the ancient Egyptian scripts in the early 19th century. Egyptian is one of the earliest known written languages, first recorded in the hieroglyphic script in the late 4th millennium BC. It is also the longest-attested human language, with a written record spanning over 4,000 years.[7] Its classical form is known as "Middle Egyptian." This was the vernacular of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, and it remained the literary language of Egypt until the Roman period. By the time of classical antiquity, the spoken language had evolved into Demotic, and by the Roman era it had diversified into the Coptic dialects. These were eventually supplanted by Arabic after the Muslim conquest of Egypt, although Bohairic Coptic remains in use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Church.[8][note 2]

Classification

The Egyptian language branch belongs to the Afroasiatic language family.[9][10] Among the typological features of Egyptian that are typically Afroasiatic are its fusional morphology, nonconcatenative morphology, a series of emphatic consonants, a three-vowel system /a i u/, a nominal feminine suffix *-at, a nominal prefix m-, an adjectival suffix -ī and characteristic personal verbal affixes.[9] Of the other Afroasiatic branches, linguists have variously suggested that the Egyptian language shares its greatest affinities with Berber[11] and Semitic[10][12][13] languages, particularly Arabic[citation needed] (which is spoken in Egypt today) and Hebrew.[10] However, other scholars have argued that the Egyptian language shared closer linguistic ties with northeastern African regions.[14][15][16]

There are two theories that seek to establish the cognate sets between Egyptian and Afroasiatic, the traditional theory and the neuere Komparatistik, founded by Semiticist Otto Rössler.[17] According to the neuere Komparatistik, in Egyptian, the Proto-Afroasiatic voiced consonants */d z ð/ developed into pharyngeal ⟨ꜥ⟩ /ʕ/: Egyptian ꜥr.t 'portal', Semitic dalt 'door'. The traditional theory instead disputes the values given to those consonants by the neuere Komparatistik, instead connecting ⟨ꜥ⟩ with Semitic /ʕ/ and /ɣ/.[18] Both schools agree that Afroasiatic */l/ merged with Egyptian ⟨n⟩, ⟨r⟩, ⟨ꜣ⟩, and ⟨j⟩ in the dialect on which the written language was based, but it was preserved in other Egyptian varieties. They also agree that original */k g ḳ/ palatalise to ⟨ṯ j ḏ⟩ in some environments and are preserved as ⟨k g q⟩ in others.[19][20]

The Egyptian language has many biradical and perhaps monoradical roots, in contrast to the Semitic preference for triradical roots. Egyptian is probably more conservative, and Semitic likely underwent later regularizations converting roots into the triradical pattern.[21]

Although Egyptian is the oldest Afroasiatic language documented in written form, its morphological repertoire is very different from that of the rest of the Afroasiatic languages in general, and Semitic languages in particular. There are multiple possibilities: perhaps Egyptian had already undergone radical changes from Proto-Afroasiatic before it was recorded; or the Afroasiatic family has so far been studied with an excessively Semitocentric approach; or, as G. W. Tsereteli suggests, Afroasiatic is an allogenetic rather than a genetic group of languages.[22]

History

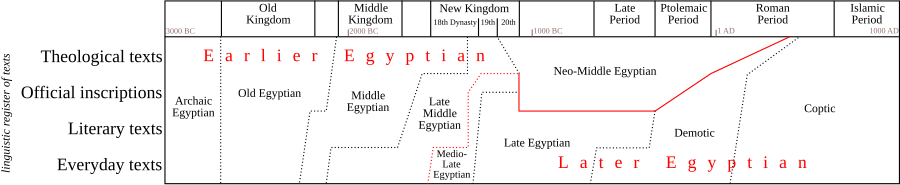

The Egyptian language can be grouped thus:[23][24]

- Egyptian

- Earlier Egyptian, Older Egyptian, or Classical Egyptian

- Old Egyptian

- Early Egyptian, Early Old Egyptian, Archaic Old Egyptian, Pre-Old Egyptian, or archaic Egyptian

- standard Old Egyptian

- Middle Egyptian

- Old Egyptian

- Later Egyptian

- Late Egyptian

- Demotic Egyptian

- Coptic

- Earlier Egyptian, Older Egyptian, or Classical Egyptian

The Egyptian language is conventionally grouped into six major chronological divisions:[25]

- Archaic Egyptian (before 2600 BC), the reconstructed language of the Early Dynastic Period,

- Old Egyptian (c. 2600 – 2000 BC), the language of the Old Kingdom,

- Middle Egyptian (c. 2000 – 1350 BC), the language of the Middle Kingdom to early New Kingdom and continuing on as a literary language into the 4th century,

- Late Egyptian (c. 1350 – 700 BC), Amarna period to Third Intermediate Period,

- Demotic Egyptian (c. 700 BC – 400 AD), the vernacular of the Late Period, Ptolemaic and early Roman Egypt,

- Coptic (after c. 200 AD), the vernacular at the time of Christianisation, and the liturgical language of Egyptian Christianity.

Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian were all written using both the hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts. Demotic is the name of the script derived from the hieratic beginning in the 7th century BC.

The Coptic alphabet was derived from the Greek alphabet, with adaptations for Egyptian phonology. It was first developed in the Ptolemaic period, and gradually replaced the Demotic script in about the 4th to 5th centuries of the Christian era.

Old Egyptian

The term "Archaic Egyptian" is sometimes reserved for the earliest use of hieroglyphs, from the late fourth through the early third millennia BC. At the earliest stage, around 3300 BC,[26] hieroglyphs were not a fully developed writing system, being at a transitional stage of proto-writing; over the time leading up to the 27th century BC, grammatical features such as nisba formation can be seen to occur.[26][27]

Old Egyptian is dated from the oldest known complete sentence, including a finite verb, which has been found. Discovered in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen (dated c. 2690 BC), the seal impression reads:

d(m)ḏ.n.f tꜣ-wj n zꜣ.f nsw.t-bj.t(j) pr-jb.sn(j) unite.PRF.he[28] land.two for son.his sedge-bee house-heart.their "He has united the Two Lands for his son, Dual King Peribsen."[29]

Extensive texts appear from about 2600 BC.[27] The Pyramid Texts are the largest body of literature written in this phase of the language. One of its distinguishing characteristics is the tripling of ideograms, phonograms, and determinatives to indicate the plural. Overall, it does not differ significantly from Middle Egyptian, the classical stage of the language, though it is based on a different dialect.

In the period of the 3rd dynasty (c. 2650 – c. 2575 BC), many of the principles of hieroglyphic writing were regularized. From that time on, until the script was supplanted by an early version of Coptic (about the third and fourth centuries), the system remained virtually unchanged. Even the number of signs used remained constant at about 700 for more than 2,000 years.[30]

Middle Egyptian

Middle Egyptian was spoken for about 700 years, beginning around 2000 BC, during the Middle Kingdom and the subsequent Second Intermediate Period.[12] As the classical variant of Egyptian, Middle Egyptian is the best-documented variety of the language, and has attracted the most attention by far from Egyptology. While most Middle Egyptian is seen written on monuments by hieroglyphs, it was also written using a cursive variant, and the related hieratic.[31]

Middle Egyptian first became available to modern scholarship with the decipherment of hieroglyphs in the early 19th century. The first grammar of Middle Egyptian was published by Adolf Erman in 1894, surpassed in 1927 by Alan Gardiner's work. Middle Egyptian has been well-understood since then, although certain points of the verbal inflection remained open to revision until the mid-20th century, notably due to the contributions of Hans Jakob Polotsky.[32][33]

The Middle Egyptian stage is taken to have ended around the 14th century BC, giving rise to Late Egyptian. This transition was taking place in the later period of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (known as the Amarna Period).[citation needed]

Egyptien de tradition

Original Old Egyptian and Middle Egyptian texts were still used after the 14th century BCE. And an emulation of predominately Middle Egyptian, but also with characteristics of Old Egyptian, Late Egyptian and Demotic, called "Égyptien de tradition" or "Neo-Middle Egyptian" by scholars, was used as a literary language for new texts since the later New Kingdom in official and religious hieroglyphic and hieratic texts in preference to Late Egyptian or Demotic. Égyptien de tradition as a religious language survived until the Christianisation of Roman Egypt in the 4th century.

Late Egyptian

Late Egyptian was spoken for about 650 years, beginning around 1350 BC, during the New Kingdom of Egypt. Late Egyptian succeeded but did not fully supplant Middle Egyptian as a literary language, and was also the language of the New Kingdom administration.[6][34]

Texts written wholly in Late Egyptian date to the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt and later. Late Egyptian is represented by a large body of religious and secular literature, comprising such examples as the Story of Wenamun, the love poems of the Chester–Beatty I papyrus, and the Instruction of Any. Instructions became a popular literary genre of the New Kingdom, which took the form of advice on proper behavior. Late Egyptian was also the language of New Kingdom administration.[35][36]

Late Egyptian is not completely distinct from Middle Egyptian, as many "classicisms" appear in historical and literary documents of this phase.[37] However, the difference between Middle and Late Egyptian is greater than the difference between Middle and Old Egyptian. Originally a synthetic language, Egyptian by the Late Egyptian phase had become an analytic language.[38] The relationship between Middle Egyptian and Late Egyptian has been described as being similar to that between Latin and Italian.[39]

- Written Late Egyptian was seemingly a better representative than Middle Egyptian of the spoken language in the New Kingdom and beyond: weak consonants ꜣ, w, j, as well as the feminine ending .t were increasingly dropped, apparently because they stopped being pronounced.

- The demonstrative pronouns pꜣ (masc.), tꜣ (fem.), and nꜣ (pl.) were used as definite articles.

- The old form sḏm.n.f (he heard) of the verb was replaced by sḏm-f which had both prospective (he shall hear) and perfective (he heard) aspects. The past tense was also formed using the auxiliary verb jr (make), as in jr.f saḥa.f (he has accused him).

- Adjectives as attributes of nouns are often replaced by nouns.

The Late Egyptian stage is taken to have ended around the 8th century BC, giving rise to Demotic.

Demotic

Demotic is a later development of the Egyptian language written in the Demotic script, following Late Egyptian and preceding Coptic, the latter of which it shares much with. In the earlier stages of Demotic, such as those texts written in the early Demotic script, it probably represented the spoken idiom of the time. However, as its use became increasingly confined to literary and religious purposes, the written language diverged more and more from the spoken form, leading to significant diglossia between the late Demotic texts and the spoken language of the time, similar to the use of classical Middle Egyptian during the Ptolemaic Period.

Coptic

Coptic is the name given to the late Egyptian vernacular when it was written in a Greek-based alphabet, the Coptic alphabet; it flourished from the time of Early Christianity (c. 31/33–324), but Egyptian phrases written in the Greek alphabet first appeared during the Hellenistic period c. 3rd century BC,[40] with the first known Coptic text, still pagan (Old Coptic), from the 1st century AD.

Coptic survived into the medieval period, but by the 16th century was dwindling rapidly due to the persecution of Coptic Christians under the Mamluks. It probably survived in the Egyptian countryside as a spoken language for several centuries after that. Coptic survives as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Coptic Catholic Church.

Dialects

Most hieroglyphic Egyptian texts are written in a literary prestige register rather than the vernacular speech variety of their author. As a result, dialectical differences are not apparent in written Egyptian until the adoption of the Coptic alphabet.[3][4] Nevertheless, it is clear that these differences existed before the Coptic period. In one Late Egyptian letter (dated c. 1200 BC), a scribe jokes that his colleague's writing is incoherent like "the speech of a Delta man with a man of Elephantine."[3][4]

Recently, some evidence of internal dialects has been found in pairs of similar words in Egyptian that, based on similarities with later dialects of Coptic, may be derived from northern and southern dialects of Egyptian.[41] Written Coptic has five major dialects, which differ mainly in graphic conventions, most notably the southern Saidic dialect, the main classical dialect, and the northern Bohairic dialect, currently used in Coptic Church services.[3][4]

Writing systemsedit

Most surviving texts in the Egyptian language are written on stone in hieroglyphs. The native name for Egyptian hieroglyphic writing is zẖꜣ n mdw-nṯr ("writing of the gods' words").[42][citation needed] In antiquity, most texts were written on perishable papyrus in hieratic and (later) demotic. There was also a form of cursive hieroglyphs, used for religious documents on papyrus, such as the Book of the Dead of the Twentieth Dynasty; it was simpler to write than the hieroglyphs in stone inscriptions, but it was not as cursive as hieratic and lacked the wide use of ligatures. Additionally, there was a variety of stone-cut hieratic, known as "lapidary hieratic".[citation needed] In the language's final stage of development, the Coptic alphabet replaced the older writing system.

Hieroglyphs are employed in two ways in Egyptian texts: as ideograms to represent the idea depicted by the pictures and, more commonly, as phonograms to represent their phonetic value.

As the phonetic realisation of Egyptian cannot be known with certainty, Egyptologists use a system of transliteration to denote each sound that could be represented by a uniliteral hieroglyph.[43]

Egyptian scholar Gamal Mokhtar argued that the inventory of hieroglyphic symbols derived from "fauna and flora used in the signs which are essentially African" and in "regards to writing, we have seen that a purely Nilotic, hence African origin not only is not excluded, but probably reflects the reality" although he acknowledged the geographical location of Egypt made it a receptacle for many influences.[44]

Phonologyedit

While the consonantal phonology of the Egyptian language may be reconstructed, the exact phonetics is unknown, and there are varying opinions on how to classify the individual phonemes. In addition, because Egyptian is recorded over a full 2,000 years, the Archaic and Late stages being separated by the amount of time that separates Old Latin from Modern Italian, significant phonetic changes must have occurred during that lengthy time frame.[45]

Phonologically, Egyptian contrasted labial, alveolar, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, and glottal consonants. Egyptian also contrasted voiceless and emphatic consonants, as with other Afroasiatic languages, but exactly how the emphatic consonants were realised is unknown. Early research had assumed that the opposition in stops was one of voicing, but it is now thought to be either one of tenuis and emphatic consonants, as in many Semitic languages, or one of aspirated and ejective consonants, as in many Cushitic languages.[note 3]

Since vowels were not written until Coptic, reconstructions of the Egyptian vowel system are much more uncertain and rely mainly on evidence from Coptic and records of Egyptian words, especially proper nouns, in other languages/writing systems.[46]

The actual pronunciations reconstructed by such means are used only by a few specialists in the language. For all other purposes, the Egyptological pronunciation is used, but it often bears little resemblance to what is known of how Egyptian was pronounced.

Old Egyptianedit

Consonantsedit

The following consonants are reconstructed for Archaic (before 2600 BC) and Old Egyptian (2686–2181 BC), with IPA equivalents in square brackets if they differ from the usual transcription scheme:

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | ṯ [c] | k | q[a] | ʔ | ||

| voiced | b | d[a] | ḏ[a] [ɟ] | ɡ[a] | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | š [ʃ] | ẖ [ç] | ḫ [χ] | ḥ [ħ] | h | |

| voiced | z[a] | ꜥ (ʿ) [ʕ] | |||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||||

| Trill | r | ꜣ (ȝ) [ʀ] | |||||||

/l/ has no independent representation in the hieroglyphic orthography, and it is frequently written as if it were /n/ or /r/.[47] That is probably because the standard for written Egyptian is based on a dialect in which /l/ had merged with other sonorants.[19] Also, the rare cases of /ʔ/ occurring are not represented. The phoneme /j/ is written as ⟨j⟩ in the initial position (⟨jt⟩ = */ˈjaːtVj/ 'father') and immediately after a stressed vowel (⟨bjn⟩ = */ˈbaːjin/ 'bad') and as ⟨jj⟩ word-medially immediately before a stressed vowel (⟨ḫꜥjjk⟩ = */χaʕˈjak/ 'you will appear') and are unmarked word-finally (⟨jt⟩ = /ˈjaːtVj/ 'father').[47]

Middle Egyptianedit

In Middle Egyptian (2055–1650 BC), a number of consonantal shifts take place. By the beginning of the Middle Kingdom period, /z/ and /s/ had merged, and the graphemes ⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ are used interchangeably.[48] In addition, /j/ had become /ʔ/ word-initially in an unstressed syllable (⟨jwn⟩ /jaˈwin/ > */ʔaˈwin/ "colour") and after a stressed vowel (⟨ḥjpw⟩ */ˈħujpVw/ > /ˈħeʔp(Vw)/ 'the god Apis').[49]

Late Egyptianedit

In Late Egyptian (1069–700 BC), the phonemes d ḏ g gradually merge with their counterparts t ṯ k (⟨dbn⟩ */ˈdiːban/ > Akkadian transcription ti-ba-an 'dbn-weight'). Also, ṯ ḏ often become /t d/, but they are retained in many lexemes; ꜣ becomes /ʔ/; and /t r j w/ become /ʔ/ at the end of a stressed syllable and eventually null word-finally: ⟨pḏ.t⟩ */ˈpiːɟat/ > Akkadian transcription -pi-ta 'bow'.[50]

Demoticedit

Phonologyedit

The most important source of information about Demotic phonology is Coptic. The consonant inventory of Demotic can be reconstructed on the basis of evidence from the Coptic dialects.[51] Demotic orthography is relatively opaque. The Demotic "alphabetical" signs are mostly inherited from the hieroglyphic script, and due to historical sound changes they do not always map neatly onto Demotic phonemes. However, the Demotic script does feature certain orthographic innovations, such as the use of the sign h̭ for /ç/,[52] which allow it to represent sounds that were not present in earlier forms of Egyptian.

The Demotic consonants can be divided into two primary classes: obstruents (stops, affricates and fricatives) and sonorants (approximants, nasals, and semivowels).[53] Voice is not a contrastive feature; all obstruents are voiceless and all sonorants are voiced.[54] Stops may be either aspirated or tenuis (unaspirated),[55] although there is evidence that aspirates merged with their tenuis counterparts in certain environments.[56]

The following table presents the consonants of Demotic Egyptian. The reconstructed value of a phoneme is given in IPA transcription, followed by a transliteration of the corresponding Demotic "alphabetical" sign(s) in angle brackets ⟨ ⟩.

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalv. | Palatal | Velar | Pharyng. | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ | /n/ | |||||||

| Obstruent | aspirate | /pʰ/ ⟨p⟩ | /tʰ/ ⟨t ṯ⟩ | /t͡ʃʰ/ ⟨ṯ⟩ | /cʰ/ ⟨k⟩ | /kʰ/ ⟨k⟩ | |||

| tenuis | /t/ ⟨d ḏ t ṯ ṱ⟩ | /t͡ʃ/ ⟨ḏ ṯ⟩ | /c/ ⟨g k q⟩ | /k/ ⟨q k g⟩ | |||||

| fricative | /f/ ⟨f⟩ | /s/ ⟨s⟩ | /ʃ/ ⟨š⟩ | /ç/ ⟨h̭ ḫ⟩ | /x/ ⟨ẖ ḫ⟩ | /ħ/ ⟨ḥ⟩ | /h/ ⟨h⟩ | ||

| Approximant | /β/ ⟨b⟩ | /r/ ⟨r⟩ | /l/ ⟨l r⟩ | /j/ ⟨y ı͗⟩ | /w/ ⟨w⟩ | /ʕ/ ⟨ꜥ⟩[a] | |||