A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Appalachia | |

|---|---|

Region | |

Left–right from top:

| |

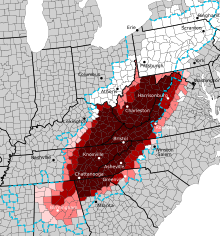

Red and dark red counties form the Appalachian Regional Commission; dark red and dark red striped counties form traditional Appalachia.[2] | |

| Coordinates: 38°48′N 81°00′W / 38.80°N 81.00°W | |

| Country | United States of America |

| Counties or county-equivalents | 420[1] |

| States | 13 |

| Largest city | Pittsburgh |

| Area | |

| • Total | 206,000 sq mi (530,000 km2) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 26.3 million[1] (Appalachian Regional Commission estimate) |

| • Density | 127.7/sq mi (49.3/km2) |

| Demonym | Appalachian |

| Dialect(s) | Appalachian English |

Appalachia (/ˌæpəˈlætʃə, -leɪtʃə, -leɪʃə/)[4] is a geographic region located in the central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States. Its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountains of New York state into Pennsylvania, continuing on through the Blue Ridge Mountains and Great Smoky Mountains into northern Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, with West Virginia being the only state in which the entire state is within the boundaries of Appalachia.[5] In 2021, the region was home to an estimated 26.3 million people, of whom roughly 80% were white.[1]

Since its recognition as a cultural region in the late 19th century, Appalachia has been a source of enduring myths and distortions regarding the isolation, temperament, and behavior of its inhabitants. Early 20th-century writers often engaged in yellow journalism focused on sensationalistic aspects of the region's culture, such as moonshining and clan feuding, portraying the region's inhabitants as uneducated and unrefined; sociology studies have since helped dispel these stereotypes.[6][7]

While endowed with abundant natural resources, Appalachia has long struggled economically and has been associated with poverty. In the early 20th century, large-scale logging and coal mining firms brought jobs and modern amenities to Appalachia, but by the 1960s the region had failed to capitalize on any long-term benefits[8] from these two industries. Beginning in the 1930s, the federal government sought to alleviate poverty in the Appalachian region with a series of New Deal initiatives, specifically the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The TVA was responsible for the construction of hydroelectric dams that provide a vast amount of electricity and that support programs for better farming practices, regional planning, and economic development.

In 1965 the Appalachian Regional Commission[9] was created to further alleviate poverty in the region, mainly by diversifying the region's economy and helping to provide better health care and educational opportunities to the region's inhabitants. By 1990 Appalachia had largely joined the economic mainstream but still lagged behind the rest of the nation in most economic indicators.[6]

Definitions

Since Appalachia lacks definite physiographical or topographical boundaries, there has been some disagreement over what the region encompasses. The most commonly used modern definition of Appalachia is the one initially defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) in 1965 and expanded over subsequent decades.[6] The region defined by the commission currently includes 420 counties and eight independent cities in 13 states, including all 55 counties in West Virginia, 14 counties in New York, 52 in Pennsylvania, 32 in Ohio, 3 in Maryland, 54 in Kentucky, 25 counties and 8 cities in Virginia,[11] 29 in North Carolina, 52 in Tennessee, 6 in South Carolina, 37 in Georgia, 37 in Alabama, and 24 in Mississippi.[5] When the commission was established, counties were added based on economic need, however, rather than any cultural parameters.[6]

The first major attempt to map Appalachia as a distinctive cultural region came in the 1890s with the efforts of Berea College president William Goodell Frost, whose "Appalachian America" included 194 counties in 8 states.[12]: 11–14 In 1921, John C. Campbell published The Southern Highlander and His Homeland in which he modified Frost's map to include 254 counties in 9 states. A landmark survey of the region in the following decade by the United States Department of Agriculture defined the region as consisting of 206 counties in 6 states. In 1984, Karl Raitz and Richard Ulack expanded the ARC's definition to include 445 counties in 13 states, although they removed all counties in Mississippi and added two in New Jersey. Historian John Alexander Williams, in his 2002 book Appalachia: A History, distinguished between a "core" Appalachian region consisting of 164 counties in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia, and a greater region defined by the ARC.[6]

In the Encyclopedia of Appalachia (2006), Appalachian State University historian Howard Dorgan suggests the term "Old Appalachia" for the region's cultural boundaries, noting an academic tendency to ignore the southwestern and northeastern extremes of the ARC's pragmatic definition.[13] The term "Greater Appalachia" was introduced by American journalist Colin Woodard in his 2011 book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. Sean Trende, senior elections analyst at RealClearPolitics, defines "Greater Appalachia" in his 2012 book The Lost Majority as including both the Appalachian Mountains region and the Upland South, following Protestant Scotch-Irish migrations to the southern and Midwestern United States in the 18th and 19th centuries.[14] The Upland South region includes the Ozark Plateau in Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, an area which is not included in the ARC definition.

Toponymy and pronunciation

While exploring inland along the northern coast of Florida in 1528, the members of the Narváez expedition, including Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, found a village of indigenous peoples near present-day Tallahassee, Florida, whose name they transcribed as Apalchen or Apalachen (IPA: [aˈpal(a)tʃen]). The name was altered by the Spanish to Apalache (Apalachee) and used as a name for the tribe and region spreading well inland to the north. Pánfilo de Narváez's expedition first entered Apalachee territory on June 15, 1528, and applied the name. Now spelled "Appalachian", it is the fourth oldest surviving European place-name in the U.S.[15] After the de Soto expedition in 1540, Spanish cartographers began to apply the name of the tribe to the Appalachian Mountain range. The first cartographic appearance of Apalchen is on Diego Gutiérrez's 1562 map; the first use for the mountain range is the 1565 map by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues.[16] Le Moyne was also the first European to apply "Apalachen" specifically to a mountain range as opposed to a village, native tribe, or a southeastern region of North America.[17]

The name was not commonly used for the whole mountain range until the late 19th century. A competing and often more popular name was the "Allegheny Mountains", "Alleghenies", and even "Alleghania".[18]

In southern U.S. dialects, the mountains are called the /æpəˈlætʃənz/, and the cultural region of Appalachia is pronounced /ˈæpəˈlætʃ(i)ə/, both with a third syllable like the "la" in "latch".[19][20] This pronunciation is favored in the "core" region in the central and southern parts of the Appalachian range. In northern U.S. dialects, the mountains are pronounced /æpəˈleɪtʃənz/ or /æpəˈleɪʃənz/. The cultural region of Appalachia is pronounced /æpəˈleɪtʃ(i)ə/, also /æpəˈleɪʃ(i)ə/, all with a third syllable like "lay". The use of northern pronunciations is controversial to some in the southern region.[21] Despite not being in Appalachia, Appalachian Trail organizations in New England popularized the occasional use of the "sh" sound for the "ch" in northern dialects in the early 20th century.[12]: 11–14

History

Early history

Native American hunter-gatherers first arrived in what is now Appalachia over 16,000 years ago. The earliest discovered site is the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Washington County, Pennsylvania, which some scientists claim is pre-Clovis culture. Several other Archaic period (8000–1000 BC) archaeological sites have been identified in the region, such as the St. Albans site in West Virginia and the Icehouse Bottom site in Tennessee. The presence of Africans in the Appalachian Mountains dates back to the 16th century with the arrival of European colonists. Enslaved Africans were first brought to America during the 16th-century Spanish expeditions to the mountainous regions of the South. In 1526 enslaved Africans were brought to the Pee Dee River region of western North Carolina by Spanish explorer Lucas Vazquez de Ayllõn. Enslaved Africans also accompanied the expeditions of Fernando de Soto in 1540 and Juan Pardo in 1566, who both traveled through Appalachia.[22]

The de Soto and Pardo expeditions explored the mountains of South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia, and encountered complex agrarian societies consisting of Muskogean-speaking inhabitants. De Soto indicated that much of the region west of the mountains was part of the domain of Coosa, a paramount chiefdom centered around a village complex in northern Georgia.[23] By the time English explorers arrived in Appalachia in the late 17th century, the central part of the region was controlled by Algonquian tribes (namely the Shawnee), and the southern part of the region was controlled by the Cherokee. The French based in modern-day Quebec also made inroads into the northern areas of the region in modern-day New York state and Pennsylvania. By the mid-18th century the French had outposts such as Fort Duquesne and Fort Le Boeuf controlling the access points of the Allegheny River and upper Ohio River valleys after exploration by Celeron de Bienville.

European migration into Appalachia began in the 18th century. As lands in eastern Pennsylvania, the Tidewater region of Virginia and the Carolinas filled up, immigrants began pushing further and further westward into the Appalachian Mountains. A relatively large proportion of the early backcountry immigrants were Ulster Scots—later known as "Scotch-Irish", a group mostly originating from southern Scotland and northern England, many of whom had settled in Ulster Ireland prior to migrating to America[24][25][26][27]—who were seeking cheaper land and freedom from prejudice as the Scotch-Irish were looked down upon by other more powerful elements in society.[28] Others included Germans from the Palatinate region and English settlers from the Anglo-Scottish border country. Between 1730 and 1763, immigrants trickled into western Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, and western Maryland. Thomas Walker's discovery of the Cumberland Gap in 1750 and the end of the French and Indian War in 1763 lured settlers deeper into the mountains, namely to upper east Tennessee, northwestern North Carolina, upstate South Carolina, and central Kentucky.

During the 18th century, enslaved Africans were brought to Appalachia by European settlers of trans-Appalachia Kentucky and the upper Blue Ridge Valley. According to the first census of 1790, more than 3,000 enslaved Africans were transported across the mountains into East Tennessee and more than 12,000 into the Kentucky mountains.[29] Between 1790 and 1840, a series of treaties with the Cherokee and other Native American tribes opened up lands in north Georgia, north Alabama, the Tennessee Valley, the Cumberland Plateau, and the Great Smoky Mountains.[12]: 30–44 The last of these treaties culminated in the removal of the bulk of the Cherokee population (as well as Choctaw, Chickasaw and others) from the region via the Trail of Tears in the 1830s.

Appalachian frontier

Appalachian frontiersmen have long been romanticized for their ruggedness and self-sufficiency. A typical depiction of an Appalachian pioneer involves a hunter wearing a coonskin cap and buckskin clothing, and sporting a long rifle and shoulder-strapped powder horn. Perhaps no single figure symbolizes the Appalachian pioneer more than Daniel Boone, a long hunter and surveyor instrumental in the early settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee. Like Boone, Appalachian pioneers moved into areas largely separated from "civilization" by high mountain ridges and had to fend for themselves against the elements. As many of these early settlers were living on Native American lands, attacks from Native American tribes were a continuous threat until the 19th century.[30]: 7–13, 19

As early as the 18th century, Appalachia (then known simply as the "backcountry") began to distinguish itself from its wealthier lowland and coastal neighbors to the east. Frontiersmen often argued with lowland and tidewater elites over taxes, sometimes to the point of armed revolts such as the Regulator Movement (1767–1771) in North Carolina.[31]: 59–69 In 1778, at the height of the American Revolution, backwoodsmen from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and what is now Kentucky took part in George Rogers Clark's Illinois campaign. Two years later, a group of Appalachian frontiersmen known as the Overmountain Men routed British forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain after rejecting a call by the British to disarm.[12]: 64–68 After the war, residents throughout the Appalachian backcountry—especially the Monongahela region in western Pennsylvania and antebellum northwestern Virginia (now the north-central part of West Virginia)—refused to pay a tax placed on whiskey by the new American government, leading to what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion.[12]: 118–19 The resulting tighter federal controls in the Monongahela valley resulted in many whiskey/bourbon makers migrating via the Ohio River to Kentucky and Tennessee where the industry could flourish.

Early 19th century

In the early 19th century, the rift between the yeoman farmers of Appalachia and their wealthier lowland counterparts continued to grow, especially as the latter dominated most state legislatures. People in Appalachia began to feel slighted over what they considered unfair taxation methods and lack of state funding for improvements (especially for roads). In the northern half of the region, the lowland elites consisted largely of industrial and business interests, whereas in the parts of the region south of the Mason–Dixon line, the lowland elites consisted of large-scale land-owning planters.[31]: 59–69 The Whig Party, formed in the 1830s, drew widespread support from disaffected Appalachians.

Tensions between the mountain counties and state governments sometimes reached the point of mountain counties threatening to break off and form separate states. In 1832, bickering between western Virginia and eastern Virginia over the state's constitution led to calls on both sides for the state's separation into two states.[12]: 141 In 1841, Tennessee state senator (and later U.S. president) Andrew Johnson introduced legislation in the Tennessee Senate calling for the creation of a separate state in East Tennessee. The proposed state would have been known as "Frankland" and would have invited like-minded mountain counties in Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama to join it.[32]

Proposal to rename the United States

In 1839 Washington Irving proposed to rename the United States "Alleghania" or "Appalachia" in place of "America", since the latter name belonged to Latin America too.[12] Edgar Allan Poe later took up the idea and considered Appalachia a much better name than America or Alleghania; he thought it better defined the United States as a distinct geographical entity, separate from the rest of the Americas, and he also thought it did honor to both Irving and the natives after whom the Appalachian Mountains had been named.[33] At the time, however, the United States had already reached far beyond the greater Appalachian region, but the "magnificence" of Appalachia Poe considered enough to rechristen the nation with a name that would be unique to its character. However, Poe's popular influence only grew decades after his death, and so the name was never seriously considered.

U.S. Civil War

By 1860, the Whig Party had disintegrated. Sentiments in northern Appalachia had shifted to the pro-abolitionist Republican Party. In southern Appalachia, abolitionists still constituted a radical minority, although several smaller opposition parties (most of which were both pro-Union and pro-slavery) were formed to oppose the planter-dominated Southern Democrats. As states in the southern United States moved toward secession, a majority of southern Appalachians still supported the Union.[34] In 1861, a Minnesota newspaper identified 161 counties in southern Appalachia—which the paper called "Alleghenia"—where Union support remained strong, and which might provide crucial support for the defeat of the Confederacy.[12]: 11–14 However, many of these Unionists—especially in the mountain areas of North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama—were "conditional" Unionists in that they opposed secession but also opposed violence to prevent secession, and thus when their respective state legislatures voted to secede their support shifted to the Confederacy.[12]: 160–65 Kentucky sought to remain neutral at the outset of the conflict, opting not to supply troops to either side. After Virginia voted to secede, several mountain counties in northwestern Virginia rejected the ordinance and with the help of the Union Army established a separate state, admitted to the Union as West Virginia in 1863. However, half the counties included in the new state, comprising two-thirds of its territory, were secessionist and pro-Confederate.[35]

This caused great difficulty for the Unionist state government in Wheeling, both during and after the war.[36] A similar effort occurred in East Tennessee. Still, the initiative failed after Tennessee's governor ordered the Confederate Army to occupy the region, forcing East Tennessee's Unionists to flee to the north or go into hiding.[12]: 160–65 The one exception was the so-called Free and Independent State of Scott.[37]

Both central and southern Appalachia suffered tremendous violence and turmoil during the Civil War. While there were two major theaters of operation in the region—namely the Shenandoah Valley and the Chattanooga area—much of the violence was caused by bushwhackers and guerrilla warfare. The northernmost battles of the war were fought in Appalachia with the Battle of Buffington Island and the Battle of Salineville resulting from Morgan's Raid. Large numbers of livestock were killed (grazing was an important part of Appalachia's economy), and numerous farms were destroyed, pillaged, or neglected.[34] The actions of both Union and Confederate armies left many inhabitants in the region resentful of government authority and suspicious of outsiders for decades after the war.[31]: 109–23 [30]: 39–45

Late 19th and early 20th centuries

Economic boom

After the Civil War, northern Appalachia experienced an economic boom. At the same time, economies in the southern region stagnated, especially as Southern Democrats regained control of their respective state legislatures at the end of Reconstruction.[34] Pittsburgh as well as Knoxville grew into major industrial centers, especially regarding iron and steel production. By 1900, the Chattanooga area of north Georgia and northern Alabama had experienced similar changes with manufacturing booms in Atlanta and Birmingham at the edge of the Appalachian region. Railroad construction gave the greater nation access to the vast coalfields in central Appalachia, making its economy greatly dependent on coal mining. As the nationwide demand for lumber skyrocketed, lumber firms turned to the virgin forests of southern Appalachia, using sawmill and logging railroad innovations to reach remote timber stands. The Tri-Cities area of Tennessee and Virginia and the Kanawha Valley of West Virginia became major petrochemical production centers.[31]: 131–141

Stereotypes

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw the development of various regional stereotypes. Attempts by President Rutherford B. Hayes to enforce the whiskey tax in the late 1870s led to an explosion in violence between Appalachian "moonshiners" and federal "revenuers" that lasted through the Prohibition period in the 1920s.[12]: 187–193 The breakdown of authority and law enforcement during the Civil War may have contributed to an increase in clan feuding, which by the 1880s was reported to be a problem across most of Kentucky's Cumberland region as well as Carter County, Tennessee; Carroll County, Virginia; and Mingo and Logan counties in West Virginia.[31]: 109–23 [12]: 187–93 Regional writers from this period such as Mary Noailles Murfree and Horace Kephart liked to focus on such sensational aspects of mountain culture, leading readers outside the region to believe they were more widespread than in reality. In an 1899 article in The Atlantic, Berea College president William G. Frost attempted to redefine the inhabitants of Appalachia as "noble mountaineers"—relics of the nation's pioneer period whose isolation had left them unaffected by modern times.[31]: 109–23

Entering the 21st century, residents of Appalachia are viewed by many Americans as uneducated and unrefined, resulting in culture-based stereotyping and discrimination in many areas, including employment and housing. Such discrimination has prompted some to seek redress under prevailing federal and state civil rights laws.[38]

Feuds

Appalachia, and especially Kentucky, became nationally known for its violent feuds, especially in the remote mountain districts.[citation needed] They pitted the men in extended clans against each other for decades, often using assassination and arson as weapons, along with ambushes, gunfights, and pre-arranged shootouts. The infamous Hatfield-McCoy Feud was the best-known of these family feuds. Some of the feuds were continuations of violent local Civil War episodes.[39] Journalists often wrote about the violence, using stereotypes that "city folks" had developed about Appalachia; they interpreted the feuds as the natural products of profound ignorance, poverty, and isolation, and perhaps even inbreeding. In reality, the leading participants were typically well-to-do local elites with networks of clients who, like the Northeast and Chicago political machines, fought for their power over local and regional politics.[40]

Modern Appalachia

Logging firms' rapid devastation of the forests of the Appalachians sparked a movement among conservationists to preserve what remained and allow the land to "heal". In 1911, Congress passed the Weeks Act, giving the federal government authority to create national forests east of the Mississippi River and control timber harvesting. Regional writers and business interests led a movement to create national parks in the eastern United States similar to Yosemite and Yellowstone in the west, culminating in the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Shenandoah National Park, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, and the Blue Ridge Parkway in the 1930s.[31]: 200–210 During the same period, New England forester Benton MacKaye led the movement to build the 2,175-mile (3,500 km) Appalachian Trail, stretching from Georgia to Maine.

Several significant moments of investment by the United States government into areas of science and technology were established in the mid-20th century, notably with NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, crucial with the design of Apollo program launch vehicles and propulsion of the Space Shuttle program,[41] and at adjacent facilities Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee with the Manhattan Project and advancements in supercomputing and nuclear power.[42]

By the 1950s, poor farming techniques and the loss of jobs to mechanization in the mining industry had left much of central and southern Appalachia poverty-stricken. The lack of jobs also led to widespread difficulties with outmigration. Beginning in the 1930s, federal agencies such as the Tennessee Valley Authority began investing in the Appalachian region.[12]: 310–12 Sociologists such as James Brown and Cratis Williams and authors such as Harry Caudill and Michael Harrington brought attention to the region's plight in the 1960s, prompting Congress to create the Appalachian Regional Commission in 1965. The commission's efforts helped to stem the tide of outmigration and diversify the region's economies.[31]: 200–210 Although there have been drastic improvements in the region's economic conditions since the commission's founding, the ARC listed 80 counties as "distressed" in 2020, with nearly half of them (38) in Kentucky.[43]

Since the 1980s, population growth in southern Appalachia has brought about concerns of farmland loss and hazards to the local environment. Regarding housing development, exurban development, characterized by its low-density housing, has violated the habitats of native species and contributed significantly to the decline in agricultural land use in larger Appalachia.[44]

There are growing IT sectors in many parts of the region.[45][46] Frontier, the fastest supercomputer in the world, is housed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.[47] In the 21st century, Appalachia has swung heavily towards the Republican Party.[48]

Cities

Due to topographic considerations, several major cities are located near but not included in Appalachia. These include Cincinnati, Ohio, Cleveland, Ohio, Nashville, Tennessee, and Atlanta, Georgia. Pittsburgh is the largest city by population to be sometimes considered within the Appalachian region.

As defined by the 2020 census, the following metropolitan statistical areas and micropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) are sometimes included as part of Appalachia:[citation needed]