A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article's lead section may be too long. (June 2024) |

| |||||

| Hebrew Bible (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

The Book of Enoch (also 1 Enoch;[a] Hebrew: סֵפֶר חֲנוֹךְ, Sēfer Ḥănōḵ; Ge'ez: መጽሐፈ ሄኖክ, Maṣḥafa Hēnok) is an ancient Hebrew apocalyptic religious text, ascribed by tradition to the patriarch Enoch who was the father of Methuselah and the great-grandfather of Noah.[1][2] The Book of Enoch contains unique material on the origins of demons and Nephilim, why some angels fell from heaven, an explanation of why the Genesis flood was morally necessary, and a prophetic exposition of the thousand-year reign of the Messiah. Three books are traditionally attributed to Enoch, including the distinct works 2 Enoch and 3 Enoch.

None of the three books are considered to be canonical scripture by the majority of Jewish or Christian church bodies.

The older sections of 1 Enoch (mainly in the Book of the Watchers) are estimated to date from about 300–200 BC, and the latest part (Book of Parables) is probably to 100 BC.[3]

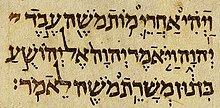

Modern scholars believe that Enoch was originally written in either Aramaic or Hebrew, the languages first used for Jewish texts; Ephraim Isaac suggests that the Book of Enoch, like the Book of Daniel, was composed partially in Aramaic and partially in Hebrew.[4]: 6 No Hebrew version is known to have survived.

The individuals residing in the Qumran Caves, where the Dead Sea Scrolls and the book were unearthed, were not aligned with the mainstream Jewish sect of the time known as the Pharisees. Instead, they were affiliated with one of several splinter groups called the Essenes, who adhered to distinctive practices. Hence, the Book of Enoch, alongside numerous other texts discovered in the caves, is recognized for its substantial variance from Rabbinic Judaism.[5]

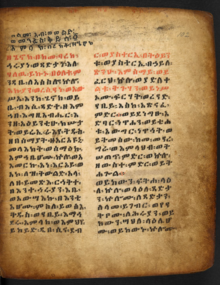

Authors of the New Testament were also familiar with some content of the story.[6] A short section of 1 Enoch (1:9) is cited in the New Testament Epistle of Jude, Jude 1:14–15, and is attributed there to "Enoch the Seventh from Adam" (1 Enoch 60:8), although this section of 1 Enoch is a midrash on Deuteronomy 33:2. Several copies of the earlier sections of 1 Enoch were preserved among the Dead Sea Scrolls.[2] Today, The Book of Enoch only survives in its entirety in Ge'ez (Ethiopic) translation.

It is part of the biblical canon used by the Ethiopian Jewish community Beta Israel, as well as the Christian Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Other Jewish and Christian groups generally regard it as non-canonical or non-inspired, but may accept it as having some historical or theological interest.

Canonicity

Judaism

Based on the number of copies found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Book of Enoch was widely read during the Second Temple period. Today, the Ethiopic Beta Israel community of Haymanot Jews is the only Jewish group that accepts the Book of Enoch as canonical and still preserves it in its liturgical language of Geʽez, where it plays a central role in worship.[7] Apart from this community, the Book of Enoch was excluded from both the formal canon of the Tanakh and the Septuagint and therefore, also from the writings known today as the Deuterocanon.[8][9]

The main reason for Jewish rejection of the book is that it is inconsistent with the teachings of the Torah. From the standpoint of Rabbinic Judaism, the book is considered to be heretical. For example, in 1 Enoch 40:1–10, the angel Phanuel (who is not mentioned elsewhere in scripture) presides over those who repent of sin and are granted eternal life. Some claim that this refers to Jesus Christ, as "Phanuel" translates to "the Face of God".[b]

Another reason for the exclusion of the texts might be the textual nature of several early sections of the book that make use of material from the Torah; for example, 1 En 1 is a midrash of Deuteronomy 33.[10][c] The content, particularly detailed descriptions of fallen angels, would also be a reason for rejection from the Hebrew canon at this period – as illustrated by the comments of Trypho the Jew when debating with Justin Martyr on this subject: "The utterances of God are holy, but your expositions are mere contrivances, as is plain from what has been explained by you; nay, even blasphemies, for you assert that angels sinned and revolted from God."[13]

Christianity

By the fifth century, the Book of Enoch was mostly excluded from Christian biblical canons, and it is now regarded as scripture only by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[14][15][16]

References in the New Testament

"Enoch, the seventh from Adam" is quoted in Jude 1:14–15:

- And Enoch also, the seventh from Adam, prophesied of these, saying, Behold, the Lord cometh with ten thousands of his saints, To execute judgment upon all, and to convict all that are ungodly among them of all their ungodly deeds which they have ungodly committed, and of all their hard speeches which ungodly sinners have spoken against him.

Compare this with Enoch 1:9, translated from the Ethiopic (found also in Qumran scroll 4Q204=4QEnochc ar, col I 16–18):[17][18]

- And behold! He cometh with ten thousands of His Saints to execute judgment upon all, and to destroy all the ungodly: And to convict all flesh of all the works of their ungodliness which they have ungodly committed, and of all the hard things which ungodly sinners have spoken against Him.

Compare this also with what may be the original source of 1 Enoch 1:9 in Deuteronomy 33:2: In "He cometh with ten thousands of His holy ones" the text reproduces the Masoretic of Deuteronomy 33 in reading אָתָא = ἔρκεται, whereas the three Targums, the Syriac and Vulgate read אִתֹּה, = μετ' αὐτοῦ. Here the Septuagint diverges wholly. The reading אתא is recognized as original. The writer of 1–5 therefore used the Hebrew text and presumably wrote in Hebrew.[19][d][e]

The Lord came from Sinai and dawned from Seir upon us; he shone forth from Mount Paran; he came from the ten thousands of Saints, with flaming fire at his right hand.

Under the heading of canonicity, it is not enough to merely demonstrate that something is quoted. Instead, it is necessary to demonstrate the nature of the quotation.[22]

In the case of the Jude 1:14 quotation of 1 Enoch 1:9, it would be difficult to argue that Jude does not quote Enoch as a historical prophet, since he cites Enoch by name. However, there remains a question as to whether the author of Jude attributed the quotation believing the source to be the historical Enoch before the flood or a midrash of Deut 33:2–3.[24][25][26] The Greek text might seem unusual in stating that "Enoch the Seventh from Adam" prophesied "to" (dative case) not "of" (genitive case) the men, however, this Greek grammar might indicate meaning "against them" – the dative τούτοις as a dative of disadvantage (dativus incommodi).[f]

Davids (2006)[28] points to Dead Sea Scrolls evidence but leaves it open as to whether Jude viewed 1 Enoch as canon, deuterocanon, or otherwise: "Did Jude, then, consider this scripture to be like Genesis or Isaiah? Certainly he did consider it authoritative, a true word from God. We cannot tell whether he ranked it alongside other prophetic books such as Isaiah and Jeremiah. What we do know is, first, that other Jewish groups, most notably those living in Qumran near the Dead Sea, also used and valued 1 Enoch, but we do not find it grouped with the scriptural scrolls."[28]

The attribution "Enoch the Seventh from Adam" is apparently itself a section heading taken from 1 Enoch (1 Enoch 60:8, Jude 1:14a) and not from Genesis.[23][full citation needed]

Enoch is referred to directly in the Epistle to the Hebrews. The epistle mentions that Enoch received testimony from God before his translation,(Hebrews 11:5) which may be a reference to 1 Enoch.

It has also been alleged that the First Epistle of Peter (1 Peter 3:19–20) and the Second Epistle of Peter (2 Peter 2:4–5) make reference to some Enochian material.[29]

Reception

The Book of Enoch was considered as scripture in the Epistle of Barnabas (4:3)[30] and by some of the early church Fathers, such as Athenagoras,[31] Clement of Alexandria,[32] and Tertullian,[33] who wrote c. 200 that the Book of Enoch had been rejected by the Jews because it purportedly contained prophecies pertaining to Christ.[34]

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not consider 1 Enoch to be part of its standard canon, although it believes that a purported "original" Book of Enoch was an inspired book.[35] The Mormon Book of Moses, first published in the 1830s, is part of the standard works of the Church, and has a section which claims to contain extracts from the "original" Book of Enoch. This section has many similarities to 1 Enoch and other Enoch texts, including 2 Enoch, 3 Enoch, and The Book of Giants.[36] The Enoch section of the Book of Moses is believed by the Church to contain extracts from "the ministry, teachings, and visions of Enoch", though it does not contain the entire Book of Enoch itself. The Church considers the portions of the other texts which match its Enoch excerpts to be inspired, while not rejecting but withholding judgment on the remainder.[37][38][39]

Manuscript tradition

Ethiopic

The most extensive surviving early manuscripts of the Book of Enoch exist in the Ge'ez language. Robert Henry Charles's critical edition of 1906 subdivides the Ethiopic manuscripts into two families:

Family α: thought to be more ancient and more similar to the earlier Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek versions:

- A – ms. orient. 485 of the British Museum, 16th century, with Jubilees

- B – ms. orient. 491 of the British Museum, 18th century, with other biblical writings

- C – ms. of Berlin orient. Petermann II Nachtrag 29, 16th century

- D – ms. abbadiano 35, 17th century

- E – ms. abbadiano 55, 16th century

- F – ms. 9 of the Lago Lair, 15th century

Family β: more recent, apparently edited texts

- G – ms. 23 of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 18th century

- H – ms. orient. 531 of the Bodleian Library of Oxford, 18th century

- I – ms. Brace 74 of the Bodleian Library of Oxford, 16th century

- J – ms. orient. 8822 of the British Museum, 18th century

- K – ms. property of E. Ullendorff of London, 18th century

- L – ms. abbadiano 99, 19th century

- M – ms. orient. 492 of the British Museum, 18th century

- N – ms. Ethiopian 30 of Munich, 18th century

- O – ms. orient. 484 of the British Museum, 18th century

- P – ms. Ethiopian 71 of the Vatican, 18th century

- Q – ms. orient. 486 of the British Museum, 18th century, lacking chapters 1–60

Additionally, there are the manuscripts[which?] used by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church for preparation of the deuterocanonicals from Ge'ez into the targumic Amharic in the bilingual Haile Selassie Amharic Bible (Mashaf qeddus bage'ezenna ba'amaregna yatasafe 4 vols. c. 1935[when?]).[40]

Aramaic

Eleven Aramaic-language fragments of the Book of Enoch were found in cave 4 of Qumran in 1948[41] and are in the care of the Israel Antiquities Authority. They were translated for and discussed by Józef Milik and Matthew Black in The Books of Enoch.[42] Another translation has been released by Vermes[43][full citation needed] and Garcia-Martinez.[44] Milik described the documents as being white or cream in color, blackened in areas, and made of leather that was smooth, thick and stiff. It was also partly damaged, with the ink blurred and faint.

- 4Q201 = 4QEnoch a ar, Enoch 2:1–5:6; 6:4–8:1; 8:3–9:3,6–8

- 4Q202 = 4QEnoch b ar, Enoch 5:9–6:4, 6:7–8:1, 8:2–9:4, 10:8–12, 14:4–6

- 4Q204 = 4QEnoch c ar, Enoch 1:9–5:1, 6:7, 10:13–19, 12:3, 13:6–14:16, 30:1–32:1, 35, 36:1–4, 106:13–107:2

- 4Q205 = 4QEnoch d ar; Enoch 89:29–31, 89:43–44

- 4Q206 = 4QEnoch e ar; Enoch 22:3–7, 28:3–29:2, 31:2–32:3, 88:3, 89:1–6, 89:26–30, 89:31–37

- 4Q207 = 4QEnoch f ar

- 4Q208 = 4QEnastr a ar

- 4Q209 = 4QEnastr b ar; Enoch 79:3–5, 78:17, 79:2 and large fragments that do not correspond to any part of the Ethiopian text

- 4Q210 = 4QEnastr c ar; Enoch 76:3–10, 76:13–77:4, 78:6–8

- 4Q211 = 4QEnastr d ar; large fragments that do not correspond to any part of the Ethiopian text

- 4Q212 = 4QEn g ar; Enoch 91:10, 91:18–19, 92:1–2, 93:2–4, 93:9–10, 91:11–17, 93:11–93:1

Greek

The 8th-century work Chronographia Universalis by the Byzantine historian George Syncellus preserved some passages of the Book of Enoch in Greek (6:1–9:4, 15:8–16:1). Other Greek fragments known are:

- Codex Panopolitanus (Cairo Papyrus 10759), named also Codex Gizeh or Akhmim fragments, consists of fragments of two 6th-century papyri containing portions of chapters 1–32 recovered by a French archeological team at Akhmim in Egypt and published five years later, in 1892.

According to Elena Dugan, this Codex was written by two separate scribes and was previously misunderstood as containing errors. She suggests that the first scribe actually preserves a valuable text that is not erroneous. In fact the text preserves "a thoughtful composition, corresponding to the progression of Enoch's life and culminating in an ascent to heaven". The first scribe may have been working earlier, and was possibly unconnected to the second.[45]

- Vatican Fragments, f. 216v (11th century): including 89:42–49

- Chester Beatty Papyri XII : including 97:6–107:3 (less chapter 105)

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri 2069: including only a few letters, which made the identification uncertain, from 77:7–78:1, 78:1–3, 78:8, 85:10–86:2, 87:1–3

It has been claimed that several small additional fragments in Greek have been found at Qumran (7QEnoch: 7Q4, 7Q8, 7Q10-13), dating about 100 BC, ranging from 98:11? to 103:15[46] and written on papyrus with grid lines, but this identification is highly contested.

Portions of 1 Enoch were incorporated into the chronicle of Panodoros (c. 400) and thence borrowed by his contemporary Annianos.[47]

Coptic

A sixth- or seventh-century fragmentary manuscript contains a Coptic version of the Apocalypse of Weeks. How extensive the Coptic text originally was cannot be known. It agrees with the Aramaic text against the Ethiopic, but was probably derived from Greek.[48]

Latin

Of the Latin translation, only 1:9 and 106:1–18 are known. The first passage occurs in the Pseudo-Cyprianic Ad Novatianum and the Pseudo-Vigilian Contra Varimadum;[49] the second was discovered in 1893 by M. R. James in an 8th-century manuscript in the British Museum and published in the same year.[50]

Syriac

The only surviving example of 1 Enoch in Syriac is found in the 12th century Chronicle of Michael the Great. It is a passage from Book VI and is also known from Syncellus and papyrus. Michael's source appears to have been a Syriac translation of (part of) the chronicle of Annianos.[51]

History

Origins

Ephraim Isaac, the editor and translator of 1 Enoch in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, writes that "1 Enoch is clearly composite representing numerous periods and writers". And that the dating of the various sections spans from early pre-Maccabean (i.e. c. 200 BC) to AD 160.[52] George W. E. Nickelsburg writes that "1 Enoch is a collection of Jewish apocalyptic traditions that date from the last three centuries before the common era".[53]

Second Temple period

Paleographic analysis of the Enochic fragments found in the Qumran caves dates the oldest fragments of the Book of the Watchers to 200–150 BC.[42] Since this work shows evidence of multiple stages of composition, it is probable that this work was already extant in the 3rd century BC.[54] The same can be said about the Astronomical Book.[1]

Because of these findings, it was no longer possible to claim that the core of the Book of Enoch was composed in the wake of the Maccabean Revolt as a reaction to Hellenization.[55]: 93 Scholars thus had to look for the origins of the Qumranic sections of 1 Enoch in the previous historical period, and the comparison with traditional material of such a time showed that these sections do not draw exclusively on categories and ideas prominent in the Hebrew Bible. David Jackson speaks even of an "Enochic Judaism" from which the writers of Qumran scrolls were descended.[56] Margaret Barker argues, "Enoch is the writing of a very conservative group whose roots go right back to the time of the First Temple".[57] The main peculiar aspects of this Enochic Judaism include:

- the idea that evil and impurity on Earth originated as a result of angels that had intercourse with human women and were subsequently expelled from Heaven;[55]: 90

- the absence of references to terms of the Mosaic covenant (such as the observance of Shabbat or the rite of circumcision), as found in the Torah;[58]: 50–51

- the concept of "End of Days" as the time of final judgment that takes the place of promised earthly rewards;[55]: 92

- the rejection of the Second Temple's sacrifices considered impure: according to Enoch 89:73, the Jews, when returned from the exile, "reared up that tower (the temple) and they began again to place a table before the tower, but all the bread on it was polluted and not pure";[citation needed]

- the presentation of heaven in 1 Enoch 1–36, not in terms of the Jerusalem temple and its priests, but modelling God and his angels on an ancient near eastern or Hellenistic court, with its king and courtiers;[59]

- a solar calendar in opposition to the lunar calendar used in the Second Temple (a very important aspect for the determination of the dates of religious feasts);

- an interest in the angelic world that involves life after death.[60]

Most Qumran fragments are relatively early, with none written from the last period of the Qumranic experience. Thus, it is probable that the Qumran community gradually lost interest in the Book of Enoch.[61]

The relation between 1 Enoch and the Essenes was noted even before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[62] While there is consensus to consider the sections of the Book of Enoch found in Qumran as texts used by the Essenes, the same is not so clear for the Enochic texts not found in Qumran (mainly the Book of Parables): it was proposed[63] to consider these parts as expression of the mainstream, but not-Qumranic, essenic movement. The main peculiar aspects of the not-Qumranic units of 1 Enoch are the following:

- a Messiah called "Son of Man", with divine attributes, generated before the creation, who will act directly in the final judgment and sit on a throne of glory (1 Enoch 46:1–4, 48:2–7, 69:26–29)[18]: 562–563

- the sinners usually seen as the wealthy ones and the just as the oppressed (a theme we find also in the Psalms of Solomon).

Early influence

Classical rabbinic literature is characterized by near silence concerning Enoch. It seems plausible that rabbinic polemics against Enochic texts and traditions might have led to the loss of these books to Rabbinic Judaism.[64]

The Book of Enoch plays an important role in the history of Jewish mysticism: the scholar Gershom Scholem wrote, "The main subjects of the later Merkabah mysticism already occupy a central position in the older esoteric literature, best represented by the Book of Enoch."[65] Particular attention is paid to the detailed description of the throne of God included in chapter 14 of 1 Enoch.[1]

For the quotation from the Book of the Watchers in the New Testament Epistle of Jude:

14 And Enoch also, the seventh from Adam, prophesied of these, saying, "Behold, the Lord cometh with ten thousand of His saints 15 to execute judgment upon all, and to convince all who are ungodly among them of all their godless deeds which they have godlessly committed, and of all the harsh speeches which godless sinners have spoken against Him."

There is little doubt that 1 Enoch was influential in molding New Testament doctrines about the Messiah, the Son of Man, the messianic kingdom, demonology, the resurrection, and eschatology.[2][4]: 10 The limits of the influence of 1 Enoch are discussed at length by R.H. Charles,[66] Ephraim Isaac,[4] and G.W. Nickelsburg[67] in their respective translations and commentaries. It is possible that the earlier sections of 1 Enoch had direct textual and content influence on many Biblical apocrypha, such as Jubilees, 2 Baruch, 2 Esdras, Apocalypse of Abraham and 2 Enoch, though even in these cases, the connection is typically more branches of a common trunk than direct development.[68]

The Greek text was known to, and quoted, both positively and negatively, by many Church Fathers: references can be found in Justin Martyr, Minucius Felix, Irenaeus, Origen, Cyprian, Hippolytus, Commodianus, Lactantius and Cassian.[69]: 430 After Cassian and before the modern "rediscovery", some excerpts are given in the Byzantine Empire by the 8th-century monk George Syncellus in his chronography, and in the 9th century, it is listed as an apocryphon of the New Testament by Patriarch Nicephorus.[70]

Rediscovery

Sir Walter Raleigh, in his History of the World (written in 1616 while imprisoned in the Tower of London), makes the curious assertion that part of the Book of Enoch "which contained the course of the stars, their names and motions" had been discovered in Saba (Sheba) in the first century and was thus available to Origen and Tertullian. He attributes this information to Origen,[g] although no such statement is found anywhere in extant versions of Origen.[72]

Outside of Ethiopia, the text of the Book of Enoch was considered lost until the beginning of the seventeenth century, when it was confidently asserted that the book was found in an Ethiopic (Ge'ez) language translation there, and Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc bought a book that was claimed to be identical to the one quoted by the Epistle of Jude and the Church Fathers. Hiob Ludolf, the great Ethiopic scholar of the 17th and 18th centuries, soon claimed it to be a forgery produced by Abba Bahaila Michael.[73]

Better success was achieved by the famous Scottish traveller James Bruce, who, in 1773, returned to Europe from six years in Abyssinia with three copies of a Ge'ez version.[74] One is preserved in the Bodleian Library, another was presented to the royal library of France, while the third was kept by Bruce. The copies remained unused until the 19th century; Silvestre de Sacy, in "Notices sur le livre d'Enoch",[75] included extracts of the books with Latin translations (Enoch chapters 1, 2, 5–16, 22, and 32). From this a German translation was made by Rink in 1801.[citation needed]

The first English translation of the Bodleian / Ethiopic manuscript was published in 1821 by Richard Laurence.[76] Revised editions appeared in 1833, 1838, and 1842.

In 1838, Laurence also released the first Ethiopic text of 1 Enoch published in the West, under the title: Libri Enoch Prophetae Versio Aethiopica. The text, divided into 105 chapters, was soon considered unreliable as it was the transcription of a single Ethiopic manuscript.[77]

In 1833, Professor Andreas Gottlieb Hoffmann of the University of Jena released a German translation, based on Laurence's work, called Das Buch Henoch in vollständiger Uebersetzung, mit fortlaufendem Kommentar, ausführlicher Einleitung und erläuternden Excursen. Two other translations came out around the same time: one in 1836 called Enoch Restitutus, or an Attempt (Rev. Edward Murray) and one in 1840 called Prophetae veteres Pseudepigraphi, partim ex Abyssinico vel Hebraico sermonibus Latine bersi (A. F. Gfrörer). However, both are considered to be poor—the 1836 translation most of all—and is discussed in Hoffmann.[78][full citation needed]

The first critical edition, based on five manuscripts, appeared in 1851 as Liber Henoch, Aethiopice, ad quinque codicum fidem editus, cum variis lectionibus, by August Dillmann. It was followed in 1853 by a German translation of the book by the same author with commentary titled Das Buch Henoch, übersetzt und erklärt. It was considered the standard edition of 1 Enoch until the work of Charles.[citation needed]

The generation of Enoch scholarship from 1890 to World War I was dominated by Robert Henry Charles. His 1893 translation and commentary of the Ethiopic text already represented an important advancement, as it was based on ten additional manuscripts. In 1906 R.H. Charles published a new critical edition of the Ethiopic text, using 23 Ethiopic manuscripts and all available sources at his time. The English translation of the reconstructed text appeared in 1912, and the same year in his collection of The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament.[2]

The publication, in the early 1950s, of the first Aramaic fragments of 1 Enoch among the Dead Sea Scrolls profoundly changed the study of the document, as it provided evidence of its antiquity and original text. The official edition of all Enoch fragments appeared in 1976, by Jozef Milik.[79][2]

The renewed interest in 1 Enoch spawned a number of other translations: in Hebrew (A. Kahana, 1956), Danish (Hammershaimb, 1956), Italian (Fusella, 1981), Spanish (1982), French (Caquot, 1984) and other modern languages. In 1978 a new edition of the Ethiopic text was edited by Michael Knibb, with an English translation, while a new commentary appeared in 1985 by Matthew Black.[citation needed]

In 2001 George W.E. Nickelsburg published the first volume of a comprehensive commentary on 1 Enoch in the Hermeneia series.[58] Since the year 2000, the Enoch seminar has devoted several meetings to the Enoch literature and has become the center of a lively debate concerning the hypothesis that the Enoch literature attests the presence of an autonomous non-Mosaic tradition of dissent in Second Temple Judaism.[citation needed]

Synopsis

The first part of the Book of Enoch describes the fall of the Watchers, the angels who fathered the angel-human hybrids called Nephilim.[1] The remainder of the book describes Enoch's revelations and his visits to heaven in the form of travels, visions, and dreams.[2]

The book consists of five quite distinct major sections (see each section for details):[1]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Book_of_Enoch

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk