A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Brazilian Army | |

|---|---|

| Exército Brasileiro | |

The Brazilian Army's emblem | |

| Founded | 1822 (de facto) 1 November 1824 (de jure)[1] |

| Country | Brazil |

| Allegiance | Ministry of Defense |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size | 212,217 active (2024)[2] Over 1,000,000 reserve (2017)[3] |

| Part of | Brazilian Armed Forces |

| Command Headquarters | Brasília, Brazil |

| Nickname(s) | EB |

| Patron | The Duke of Caxias |

| Motto(s) | Braço forte, mão amiga[4] ("Strong arm, friendly hand") |

| Colors | sky blue red (heraldic colors)[5] |

| March | Canção do Exército ("Army Song") |

| Anniversaries | 19 April (Army Day)[6] |

| Equipment | See list |

| Engagements | List

|

| Website | www |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | |

| Minister of Defence | |

| Army Commander | |

| Insignia | |

| Coat of Arms |  |

| Flag |  |

|

| Brazilian Army of the Brazilian Armed Forces |

|---|

| History and future |

| Commands and components |

| Air and space command |

| Equipment |

The Brazilian Army (Portuguese: Exército Brasileiro; EB) is the branch of the Brazilian Armed Forces responsible, externally, for defending the country in eminently terrestrial operations and, internally, for guaranteeing law, order and the constitutional branches, subordinating itself, in the Federal Government's structure, to the Ministry of Defense, alongside the Brazilian Navy and Air Force. The Military Police (Polícias Militares; PMs) and Military Firefighters Corps (Corpos de Bombeiros Militares; CBMs) are legally designated as reserve and auxiliary forces to the army. Its operational arm is called Land Force. It is the largest army in South America and the largest branch of the Armed Forces of Brazil.

Emerging from the defense forces of the Portuguese Empire in Colonial Brazil as the Imperial Brazilian Army, its two main conventional warfare experiences were the Paraguayan War and the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, and its traditional rival in planning, until the 1990s, was Argentina, but the army also has many peacekeeping operations abroad and internal operations in Brazil. The Brazilian Army was directly responsible for the Proclamation of the Republic and gradually increased its capacity for political action, culminating in the military dictatorship of 1964–1985. Throughout Brazilian history, it safeguarded central authority against separatism and regionalism, intervened where unresolved social issues became violent and filled gaps left by other State institutions.

Changes in military doctrine, personnel, organization and equipment mark the history of the army, with the current phase, since 2010, known as the Army Transformation Process. Its presence strategy extends it throughout Brazil's territory, and the institution considers itself the only guarantee of Brazilianness in the most distant regions of the country. There are specialized forces for different terrains (jungle, mountain, Pantanal, Caatinga and urban) and rapid deployment forces (Army Aviation, Special Operations Command and parachute and airmobile brigades). The armored and mechanized forces, concentrated in Southern Brazil, are the most numerous on the continent, but include many vehicles nearing the end of their life cycle. The basic combined arms unit is the brigade.

Conventional military organizations train corporals and reservist soldiers through mandatory military service. There is a broad system of instruction, education and research, with the Military Academy of Agulhas Negras (Academia Militar das Agulhas Negras; AMAN) responsible for training the institution's leading elements: officers of infantry, cavalry, engineering, artillery and communications, the Quartermaster Service and the Ordnance Board. This system and the army's own health, housing and religious assistance services, are mechanisms through which it seeks to maintain its distinction from the rest of society.

Roles

The Brazilian Army is one of the three singular forces that make up the Brazilian Armed Forces, alongside the Brazilian Navy and the Air Force, all of which, according to article 142 of Brazil's constitution, act in the defense of the homeland and in guaranteeing constitutional powers and law and order, in addition to subsidiary attributions defined by complementary laws. The army forms the nation's land force, acting primarily in its external defense, but it also has a whole series of internal missions.[7][8] Its declared objectives include deterring external aggression, gaining prominence on the international stage and contributing to "sustainable development and social peace".[9]

Historically, previous Brazilian constitutions also defined external and internal functions for the Armed Forces.[10] A large workload is dedicated to the doctrine, planning, preparation and execution of law and order operations.[11] The army has a long history of internal defense and state structuring, defending political regimes and addressing threats from unresolved social issues that have resulted in internal conflicts.[12] Throughout Brazil's republican period, it is the most politically powerful of the three forces due to its past positions, its presence throughout the country's territory and its larger personnel.[13]

Covering the incompleteness of the national State, filling gaps that should have been filled by other institutions, is part of the army's culture. Through its "Presence Strategy", it occupies demographic voids, acting as a "colonizing army", whether through the military colonies it established in the 19th century or through current border posts, and sees itself as the only factor of Brazilianness in these remote regions of the country. Subsidiary roles are constant. Possibly at the expense of preparing for war, the army operates in the scientific-technological and socioeconomic fields, carries out engineering works, receives refugees (Operation Acolhida) and distributes water in Northeastern Brazil (Operation Pipa), among many other missions.[14]

- Examples of army operations

-

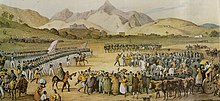

Field maneuvers

-

Occupation of Rocinha in 2008

-

Medical assistance

-

Road inspection at the borders

-

Highway works

History

The Brazilian Army originates from the defense forces of the Portuguese Empire in Colonial Brazil.[15] A Brazilian national army was designated by law for the first time in the Brazilian Empire's 1824 constitution,[16][17] but land forces had already been fighting under the Brazilian flag since the proclamation of Independence in 1822.[17] Command of these forces, until then dispersed among the viceroys and captain-generals of the captaincies, was unified under the Secretariat of State for War Affairs (later the Ministry of War) in 1822.[18]

Since 1994, the Brazilian Army has officially commemorated the First Battle of Guararapes, fought on 19 April 1648, as the moment in which the "seeds" of the institution were planted. There was still no "Brazilian nation" or Brazilian Army, however, and no current military organization in the country has institutional continuity with those that fought in 1648.[19] Several current units, however, trace their history back to the colonial period, such as the Old Terço of Rio de Janeiro, from 1567, whose heir is the 1st Mechanized Infantry Battalion.[20]

The highest authority in the army was the Adjutant General, whose body, the Adjutant General's Office, was created in 1857. The Adjutant General was always a military officer and served as an intermediary between the army and the Minister of War, whose position was a political one.[21] When the office was abolished, the chiefs of the Army General Staff (Estado-Maior do Exército; EME), created in 1899, and the Ministers of War began to compete for primacy of command.[22] The Ministry of War won the dispute.[23] In 1967, it was renamed Ministry of the Army,[24] which was later transformed into the current Army Command, subordinate to the Ministry of Defense, in 1999.[25]

19th century

First reign

The Brazilian War of Independence divided the military forces present in what is now Brazilian territory: some joined the Brazilian cause and others remained loyal to Portugal.[26] The Brazilian victory in the war did not break the continuity with the military organization and doctrine of the Portuguese Army, whose characteristics would be visible in the Brazilian institution until the beginning of the 20th century.[1][27][28] Portuguese professionals, landowners, European mercenaries and ordenanças came together in a heterogeneous army.[28][29]

The hierarchy had feudal aspects.[29] Promotion criteria were poorly defined. Some officers progressed in their careers within the institution, but others, coming from the civilian elite and the aristocracy, moved between the ranks and politics. Officers did not serve far from their birthplaces, and it was only later that service rotation in the provinces emerged.[30][31] Soldiers were generally obtained by impressment,[a] although there were volunteers, including fugitive slaves.[32] Until 1830, and again in 1851–1852, foreign mercenaries served in the ranks, and even staged a revolt of their own.[33] Military service, stigmatized,[32] was known as the "blood tribute".[34]

In December 1824, the nominal force numbered 30 thousand men of the 1st line (paid troops) and 40 thousand of the 2nd line (unpaid militia and some paid police, veterans and irregular troops). Lack of training and politicized recruitment limited the military capacity of the 2nd line.[35] The 1st line was organized into regiments, battalions and some smaller units called "corps".[36] In December 1824, it comprised three grenadier battalions, 28 caçadores (light infantry) battalions, seven cavalry regiments, five horse artillery corps and 12 field artillery corps.[37] Five brigades briefly existed in the Court (Rio de Janeiro), but throughout the century the army did not maintain large formations in peacetime. Provincial "commanders of arms" were subordinated to local governments, whose presidents were in turn appointed by the Emperor.[38] This organization would undergo numerous changes.[39] The structure of the Secretariat of State for War Affairs was small, and there was no general management body for the army in peacetime.[36]

The army was initially an instrument of emperor Pedro I's authority, closing the Constituent Assembly in 1823 (the Night of Agony) and suppressing a separatist movement, the Confederation of the Equator. Its greatest difficulty was in the Cisplatine War, when it faced logistical obstacles and a high desertion rate.[40]

Regency period

At the beginning of the regency period (1831–1840), the Liberal Party, predominant in politics, did not accept a large-scale professional military force, associating it, since previous years, with military losses in Cisplatina, mercenary revolts and the possibility of a coup.[41] The 2nd line troops were replaced by the National Guard, which was considered civilian and was outside the jurisdiction of the Secretariat of War.[39] The army did not have a monopoly on legitimate violence, which was shared with the National Guard and the justices of the peace, parish priests and police chiefs, who had authority over recruitment.[42] Personnel were drastically reduced: in 1837, the entire force numbered just 6,320 men.[43]

Faced with the numerous rebellions of the period, the political elite realized that territorial fragmentation of the country was the greatest danger and could not be controlled with the National Guard alone. Thus began the reconstruction of the army,[44] which put down the Cabanagem, Balaiada, Sabinada and Ragamuffin uprisings. It is for this reason that the Duke of Caxias, the patron of the army, is known as the "Peacemaker".[45] The army's official history emphasizes its role in ensuring national integrity.[46]

Second reign

By 1850 the political consensus was already in favor of the army.[47] The force grew to 15–16 thousand men. By the 1851 organization, the army had eight rifle battalions, six caçadores battalions, four light cavalry regiments, one horse artillery regiment, and four foot artillery battalions. These would be the "mobile corps", intended for operations in any region. A series of small corps and companies were designated "garrison corps", responsible for the internal security of the provinces.[48] Officers' careers were professionalized from 1850 onwards, with the adoption of formal criteria for advancement in the hierarchy and mandatory education in military courses.[49] The sons of the civilian nobility, who preferred to serve in the National Guard, gradually disappeared. Except in Rio Grande do Sul, officers were recruited from social groups with lower incomes, especially children of military personnel.[50]

With internal conflicts quelled, the Empire of Brazil used the army in external interventions in the Río de la Plata region. In 1851–1852, four army divisions, the National Guard and regional Argentine allies campaigned in the Platine War. The intervention was successful, but the risk of war remained in the region, and the government did not pay adequate attention to defense. When the Paraguayan War began in 1864, the Paraguayan Army had 60 thousand men, compared to 16 thousand in Brazil, whose war effort was marked by improvisation.[51] Technologies of the Second Industrial Revolution, such as the rifle, the telegraph and the observation balloon, coexisted with Napoleonic tactics, such as the infantry square, the "cult of the bayonet", cavalry as a shock weapon and artillery fired at close range, with grapeshot.[52] Lack of cartographic knowledge, good use of the terrain by the Paraguayans, logistical difficulties and epidemics delayed a decisive victory in the period before December 1868.[53]

The campaign was long and exhausting,[54] on a much larger scale than the War of Independence. Ground forces were expanded to 135,000 soldiers, including 59,000 from the National Guard and 55,000 Homeland Volunteers. At least initially, there was great popular enthusiasm for military service.[55] Three army corps were fielded.[56] The army's official history recognizes Paraguay a second historical milestone after Guararapes.[57] The institution became aware of its importance for the country, but it did not benefit after the victory in 1870: the budget was drastically reduced. Officers' nonconformity with political leaders grew. The participation of slaves in the struggle brought abolitionism to fore.[58][59][60]

A new military service law attempted to reform recruitment in 1874, but was not enforced due to popular resistance by the so-called "list rippers".[61][62] In the same year, officer education was completely separated from Civil Engineering and concentrated at the Military School of Praia Vermelha.[63]

By the end of the Empire, the officers were divided between "scientists" and "tarimbeiros": the latter, veterans of the Paraguayan War, normally without a degree, and the former, trained at Praia Vermelha. The curriculum, unrelated to military disciplines, did not produce good troop commanders but rather intellectuals, engineers, bureaucrats and politicians, who competed with civilians with degrees.[59][64] The 1888 organization defined 27 infantry units, ten cavalry units, four field artillery units, four position artillery units and two engineering units. The distinction between mobile and garrison corps disappeared. Units were very small, but would theoretically be expanded to a "war footing" when necessary, although there was no mobilization system.[65]

With no apparent external danger, the authorities used the army in public order, capturing fugitive slaves and controlling elections, which outraged the new generation of officers. New positivist ideas were spreading. In the 1880s, a series of incidents with civilian authorities, known as the Military Question, strained the army's relationship with the monarchy. The army had already become a political force, capable of making a minister resign. In the end, young officers, old leaders and civilians proclaimed the republic in a military coup that deposed emperor Pedro II.[66]

20th century

First Brazilian Republic

Until 1894, a period marked by the Federalist Revolution and the Navy Revolts, the new republican regime began under the tutelage of the army (the so-called Republic of the Sword). The military were not united and lost power to the civilian oligarchies,[67] which were alienated from the officer class[68] and transformed the Public Forces of the most powerful states into "small armies", a major obstacle to the expansion of the Armed Forces' power.[69] The period was one of struggle to assert its relevance.[70] In this context, the federal army guaranteed central power against regionalist tendencies.[71]

By the 1890s, the army's operational capacity had fallen to a level sometimes inferior to the insurgents it faced.[72] This and foreign policy fears sparked a military reform movement.[73][74][75] The First World War (1914–1918) favored reformism,[76][77] although direct Brazilian participation in land operations was limited to a mission of 26 officers to the French Army.[78] Seeking a successful army as a reference, groups of officers (known as the "Young Turks") were sent to intern in the Imperial German Army in 1906–1912,[79][80] and a French Military Mission was hired to advise on the reorganization of the Brazilian Army from 1920 to 1940.[80][81] Strategic planning had the Argentine Army as its hypothetical enemy,[82] at the time more modern and supported by a railway network that was denser than the Brazilian one.[83] Armament also had to be imported, as the arms industry was very limited.[84]

By 1919, the training of officers at the Military School of Realengo was already very different from Praia Vermelha: a curriculum dominated by professional subjects, field exercises and strict discipline, training officers with a strong sense of distinction from civilians.[85][86] The introduction of compulsory military service through the Sortition Law, in 1916 allowed the abolition of the National Guard two years later,[87] changed the army's relationship with society,[88] made recruitment more judicious[89] and allowed a gradual and continuous expansion of personnel. In the long term, this strengthened central power at the expense of regional oligarchies.[90] Military Aviation was introduced and remained in the army until 1941, when it was absorbed by the newly created Brazilian Air Force.[91]

The organization of these forces in peacetime was rudimentary until 1908, when commanders began to build a modern order of battle with regiments, brigades and divisions. In 1921 there were five infantry divisions, three cavalry divisions, a mixed brigade and independent units. The actual organization differed greatly from the formal one, with many incomplete regiments. Throughout the century, each new organization was somewhat fictional.[92][93] The force was estimated at 37 thousand men in 1919.[94]

The operational history of the period has two major conflicts arising from social issues in the interior of the country: the War of Canudos (1897) and the Contestado War (1912–1916).[45] In Canudos the force faced peasants without military training,[73] but the terrain was adverse and well used by the opponent.[95] The war concluded with the settlement of Belo Monte, in the interior of Bahia, burnt and littered by the bodies of thousands of inhabitants. The army suffered immense casualties.[96] In the 1920s the army had difficulty suppressing a mobile enemy, the Prestes Column, as its French-influenced doctrine was for a conflict in the style of the Western Front of the First World War.[97] On the other hand, the rebels were unable to threaten Rio de Janeiro.[98] In 1924 there was an experience of urban combat and the bombing of São Paulo by army artillery.[99]

Military revolts and interventions in politics marked the period, such as the proclamation of the republic itself, the Manifesto of the Thirteen Generals, Hermism/Salvations Policy, the Sergeants' Revolt of 1915, tenentism and the Revolution of 1930, which ended the First Republic. Most of the revolts involved the lower ranks and did not represent the army as a whole, damaging the hierarchy. The "Pacifying Movement", a military coup that made the 1930 Revolution triumph, differed in that it was planned by high levels of the army and navy. This was made possible by organizational changes, such as the development of the Army General Staff.[100]

Vargas Era

Getúlio Vargas' first period in power (1930–1945) was one of great modernization and expansion for the Brazilian Army,[101] which was introduced to the center of political power. The military received investments and positions in the administration.[102] But the army was deeply divided. Revolts by sergeants and corporals threatened the hierarchy, to the point of overthrowing the government of Piauí in 1931, and the officers also rebelled.[103] A large part of the São Paulo garrison joined the Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932, which was defeated due to the loyalty of the rest of the Armed Forces and state governments to Vargas.[104] Army units rose up in the Communist Uprising of 1935, which was quickly put down.[105] In 1938 the army also participated in the repression of the Integralist Uprising.[106]

To homogenize the institution, the government and army leaders carried out several purges of the officer ranks.[107][108] Revolts by young officers became less and less likely for organizational and technical reasons.[109] General Góis Monteiro, considered the "first great ideologue" of the institution, wrote about the need for the "army's politics", not "politics in the army".[110] The military aligned with the authoritarian and developmentalist ideals of the Estado Novo dictatorship, established by Vargas with a coup in 1937. The army served as the strong arm of a centralized State,[111] and the Public Forces were placed under the control of the Ministry of War, putting an end to the phenomenon of "state armies".[112] Military engineers participated in the development of the steel and oil industries in the country.[113][114] The concept of security, for the army, had been expanded, encompassing planning, energy, transport and industrialization.[115]

According to EME studies on the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution, the army had evolved in its doctrine and organization, but was still unprepared to face an external aggressor, as evidenced by the deficiency in the ammunition industry.[b] The Chaco War (1932– 1935) between Bolivia and Paraguay helped the army to continue expanding its numbers, which exceeded 60 thousand men.[116] Anti-aircraft artillery and mobile coastal artillery were implemented.[101] Later on, Brazil's entry into the Second World War in 1942 gave the army its "only experience in a conventional war along the lines of a total war".[117] Fighting alongside the Allies, Brazil received weapons (via Lend-Lease) and sent officers to study in the United States. The army's strength grew from around 80,000 men to 200,000 in 1944, organized into eight infantry divisions, three cavalry divisions and a mixed brigade.[118]

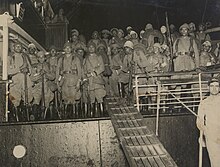

The army's participation consisted of reinforcing the northeastern salient[c] and sending the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (FEB) to the Italian Campaign. The Brazilian government promised three infantry divisions for the war effort, but due to mobilization difficulties, it was only possible to send the 1st Expeditionary Infantry Division (1st DIE),[118] subordinate to the IV Corps of the United States Army.[119] The Battle of Monte Castello, which it fought in 1944–1945, was not the most important of the IV Corps, but it stood out within the experience of the FEB, which overcame its inexperience and won after several demoralizing defeats in the offensive.[120] Tactics changed from French to American: from frontal attacks to flanking enemy positions and attacking in multiple directions.[121] The FEB was demobilized even before returning to Brazil, as it was considered a political threat.[122] This did not prevent the ousting of Vargas by the Armed Forces in 1945, after which democracy was restored. The army had changed a lot, and in addition to its technical modernization, had become politically autonomous and convinced that it could form a well-trained elite.[123]

Fourth Brazilian Republic

The Brazilian Army adopted American doctrine, organization, manuals and methods after World War II, although the absorption was partial, as older materiel of European origin and French concepts remained. New equipment was obtained through the Brazil–United States Treaty.[124][125] Since the war, motorized vehicles began to replace carts and mules. The use of armored vehicles, until then very limited, was consolidated.[126] The training of sergeants was centralized and professionalized at the Escola de Sergentos das Armas (Combatant Sergeants' School). From the 1950s onwards, sergeant revolts disappeared. The movements of enlisted personnel in the rest of the Armed Forces had less repercussions on the army.[127]

In 1960 the force comprised seven infantry divisions, four cavalry divisions, one armored division, the core of an airborne division, a mixed brigade and a School-Unit Group. These forces were grouped into four Military Zones in 1946, later called Armies in 1956, equivalent to the current Military Area Commands. The new structure was sophisticated, but the doctrine did not correspond to reality. Infantry divisions were supposed to have 15,000 men each, but averaged 5,500.[128] Officials feared Brazil's military fragility.[129] On the other hand, the relative power of neighboring countries was declining.[130] The hypothesis of war against Argentina lost relevance[131] and coexisted with concerns of the Cold War: nuclear war, revolutionary war and peace operations,[130] of which the first with Brazilian participation was the Suez battalion (1957–1967 ).[132]

The institution's political participation was continuous. In 1955, Minister of War Henrique Teixeira Lott carried out a "preventative coup", opposing the Navy and Air Force, to ensure the inauguration of president Juscelino Kubitschek. In 1961, the three military ministers (army, navy and air force) tried to veto the inauguration of João Goulart as president, but a split in the army allowed the victory of the inauguration cause.[133] Finally, the 1964 coup d'état began with the main commands of the army in loyalist hands, but officers defected en masse and the president was removed without a fight.[134] Military personnel aligned with the deposed government were purged, including 22.5% of the generals serving in 1964.[135] The ideological basis of Goulart's opponents was anti-communism,[136] developed since 1935,[137] and the doctrine of revolutionary war.[138]

Military dictatorship

In the subsequent military dictatorship (1964–1985) the center of political power was occupied by generals, although the institutions formally remained those of a liberal democracy. Generals disputed among themselves and were challenged by junior officers.[139] Political repression activities were centralized in the army,[140] whose Internal Defense Operations Centers (Centros de Operações de Defesa Interna; CODI) coordinated the Armed Forces and the police.[141] Military personnel were responsible for illegal detentions, torture, executions, forced disappearances and concealment of corpses,[142] and the army played a fundamental role in the genocide of the Waimiri-Atroari indigenous people.[143][144]

The armed struggle against the dictatorship was faced mainly by high-ranking intelligence bodies, such as the CODI and the Army Information Center (Centro de Informações do Exército; CIEx). Large-scale use of conventional troops for counterinsurgency occurred rarely and was ineffective.[141] The Araguaia Guerrilla (1972–1975), the most extensive rural insurgency of the period, could only be defeated by the principle of "fighting guerrilla with guerrilla": extensive intelligence work, infiltrated plainclothes patrols and the participation of the Special Forces Company.[145][146]

The "economic miracle" allowed the re-equipment of the army in the period 1969–1974, with a focus on conventional warfare.[147] Counterinsurgency did not make the military give up external defense, in part as a way of demonstrating the state's prestige.[148] There were two hypotheses of war: a "revolutionary war in South America" and a war between the Western and Communist blocs, with Brazil contributing an expeditionary army corps to the Western bloc.[149] Equipment inventories were rapidly nationalized thanks to the development of companies in the national arms industry, such as Engesa.[150][151] Rifles, machine guns, artillery and armor were replaced by 1980.[152]

After a century of emulating foreign armies, the Brazilian Army sought a doctrine more suited to local needs.[153][154] The order of battle was reorganized, suppressing infantry and artillery regiments and creating brigades, which became the main large maneuver units,[155] a system that still remains in the 21st century.[156] Total strength was at 170 thousand in 1970.[157] In 1980 the army fielded 13 ordinary infantry, one airborne, two jungle infantry, three armored infantry, one armored cavalry and four mechanized cavalry brigades.[158] But not all goals were met,[159] and there remained a technological delay in relation to the Argentine Army.[d]

Redemocratization and post-Cold War

Argentina's defeat in the Falklands War in 1982 shocked the Brazilian military. The United States did not support a South American country against an extracontinental power, and the Brazilian Armed Forces would clearly be out of date in a similar conflict.[160] Basic equipment was lacking and operational capacity was very low.[161] The EME began to study the hypothesis of a war with a country from the Western bloc, economically and militarily superior to Brazil, in the Amazon region,[162] at the same time that it planned the "army of the future", devising the Força Terrestre 90 (FT 90), Força Terrestre 2000 and Força Terrestre do Século XXI programs.[163][164]

After the end of the military dictatorship in 1985, the army distanced itself from political-ideological confrontation and began executing the FT 90 and its successors.[163] By the end of the 1980s, the social and economic standards of officers had declined,[165] and by the beginning of the following decade, the army's strategic priorities had become undefined.[166] Traditional threats (communism and Argentina) were giving way to non-traditional ones.[167] The United States Army once again became the "model to be followed" by winning the 1991 Gulf War, inspiring the Brazilian "Delta Doctrine".[168] The Brazilian arms industry collapsed.[169][170]

In 1991, the incursion of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) into Brazilian territory and the subsequent Operation Traíra redoubled attention in the Amazon.[171] Army officers viewed transnational crime, Colombian guerrillas, and environmental and indigenous issues as possible pretexts for foreign intervention in the region.[172] At the same time, public authorities often use the army for operations to guarantee law and order in places such as Rio de Janeiro,[173][174] as well as for subsidiary missions, which are, in a certain way, accommodated by the political class.[175] Abroad, participation in international UN missions increased.[176]

21st century

Total personnel grew from 194 thousand in 1985 to 238 thousand in 2007,[177] below the large quantitative expansion planned in the 1980s, due to budget restrictions.[178] The army of 2007, despite not being much larger than that of 1985, was more specialized, with new technologies. Electronic warfare capabilities were acquired and the roster of rapid action forces was expanded with the new Army Aviation Brigade (1989), airmobile infantry (1995) and the expansion of special operations forces (2003).[179]

The first Brazilian main battle tanks were acquired, the Leopard 1 and M60 models,[180] and the structure of Brazilian armored brigades was made equivalent to their Argentine counterparts, despite good bilateral relations.[179] An attempt was made to reduce dependence on compulsory military service, but the costs of professional soldiers limited the measures.[181][182] The Amazon Military Command's two brigades of jungle infantry were reinforced by another three.[183]

In 2012 some generals gave the press an overview of the army, describing its aging equipment and technological obsolescence. Since 2004, only 9 to 10% of the budget was available for funding and investments, with the remainder being spent on personnel.[184] The guidelines for the Army Transformation Process had just been published, with ambitious goals for the year 2030, just like the planners of the 1980s, who had defined 2010 as the year in which the "army of the future" would exist.[185] The drivers of the Transformation Process are strategic projects/programs,[186][e] such as ASTROS 2020, for the expansion of missile and rocket artillery (Astros II) and the development of a cruise missile (AV-TM 300);[187] Guarani armored vehicles, with a new family of wheeled armor;[188] Anti-Air Defense, with the renewal of low-altitude anti-aircraft artillery and acquisition of medium-altitude artillery;[189] and the Integrated Border Monitoring System, Cyber Defense and others.[190][191]

A notable peacekeeping operation during this period was the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) (2007–2017).[176] Most of the Brazilian battalion commanders in Haiti achieved generalship.[192]

The occupation of Complexo do Alemão in 2010 was the largest law and order operation since the promulgation of the 1988 Constitution, and was considered more difficult than Haiti. When confronting organized crime in Rio de Janeiro's favelas, the military had to change tactics and equipment. They recognize the difficulty of police work, in which they are not specialized and there is a risk of collateral damage. There were protests by local residents against abuses of authority, torture and excessive shooting and use of tear gas.[193] In the federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro in 2018, an army general held the position of Secretary of Security in Rio de Janeiro, and other generals held roles in that secretariat and in the federal intervention office.[194]

Strategic projects suffered from contingencies and cuts in military spending resulting from the economic crisis of the mid-2010s,[195] and by 2019 their deadlines were already being extended, some until 2040.[196][197] When the Guyana-Venezuela crisis began in 2023, the army reinforced Roraima, but still did not have cruise missiles, medium-altitude anti-aircraft defense or Centauro II tank destroyers available.[198]

Personnel

Military personnel may be on active or reserve status. If active, they may be career military personnel (with guaranteed or presumed lifetime status) or temporary personnel.[199] The number established by decree for the army in 2023 was 212,217 active military personnel, of which 149 were generals, 29,220 other officers, 46,773 warrant officers and sergeants and 136,005 corporals and soldiers.[2] Out of 214 thousand in 2023, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) quantified 112 thousand conscripts.[200] There are much lower estimates of the proportion of conscripts (30%).[201] In addition to active duty personnel, the IISS estimated the reserve at 1,340,000 military personnel in 2023, but did not distinguish between the three branches;[200] Frank McCann estimated over a million Army reservists in 2017.[3] The Brazilian Army is historically one of the largest in the region.[f]

Ranks and uniforms

Hierarchy and discipline are formally defined as the basis of the organization of the Armed Forces. In the army the hierarchy comprises 19 levels, called "postos" on the upper levels (officers), and "graduações" on the lower ones (enlisted personnel). Postos and graduações are grouped into social coexistence circles: from highest to lowest, they are the circles of general officers,[g] senior officers,[h] intermediate officers,[i] junior officers,[j] warrant officers and sergeants,[k] and corporals and soldiers. In peacetime, the highest rank is that of army general. The rank of marshal may be created in wartime.[202][203] Enlisted personnel can be called "graduados", except for soldiers, which form the lowest level of the hierarchy and are considered "non-graduated" military personnel.[204]

The greatest separation in the career is between officers and praças (enlisted men),[205] as the officers are the active leading element, trained from the beginning for command, while the enlisted men are trained to apply orders.[206] Aside from this, there are mechanisms for merit-based social mobility, and the army emphasizes that every general was once a cadet, that is, a student at the officer academy.[205]

Respect for the hierarchy must be maintained even outside of service and even upon retirement. There are rules of coexistence between different military circles (for example, sergeants and officers do not sit at the same table), and disrespecting them is known as "hierarchical promiscuity".[207] There is always a superior and a subordinate between two soldiers. Within the same position, the difference is seniority. In the case of officers from the Military Academy of Agulhas Negras, seniority is defined by the date of the last promotion or, if it is the same, which is common among officers of the same class, by the classification (final grade average) at the academy.[208][209]

Rank is indicated by insignia on the uniform, along with military organization badges and course badges and brevets. The most famous color in uniforms is olive green, which is one of the main elements of the army's visual identity. First adopted in 1931 in place of khaki, the color was also used on field uniforms until the 1990s, when the use of camouflage became widespread.[l] Olive green is the standard color for berets, but specific troops distinguish themselves by different colors: red for paratroopers, brindle for jungle troops, marine blue for aviation, gray for mountain specialists, beige for the airmobile brigade and steel blue for officer and sergeant training schools. Some units wear traditional historical uniforms, such as the Presidential Guard Battalion and the 1st Guard Cavalry Regiment.[210]

Commissioned officer ranks

The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marechal | General de exército | General de divisão | General de brigada | Coronel | Tenente-coronel | Major | Capitão | Primeiro tenente | Segundo tenente | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other ranks

The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subtenente | Primeiro-sargento | Segundo-sargento | Terceiro-sargento | Taifeiro-mor | Cabo | Taifeiro primeira classe | Taifeiro segunda classe | Soldado | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Military instruction

Military teaching and instruction can be defined as the army's main missions in peacetime.[212][213] This system encompasses education, instruction, and research.[214] Soldiers' and corporals' activities correspond to elementary education, sergeants' to secondary, technical or higher education (technologist) and officers' to higher education.[m] Practically all military organizations have some responsibility for training soldiers.[215] Active-duty organizations have a fixed personnel, but annually train a variable number of reservists. There are organizations exclusively focused on reservists: the Reserve Officer Training Bodies (Órgãos de Formação de Oficiais da Reserva; OFOR), which consist of the Preparation Centers (Centros de Preparação; CPOR) and the Preparation Nuclei (Núcleos de Preparação; NPOR), and the Tiros de Guerra.[216] Other organizations train career military personnel (officers and sergeants).[215] By law, military education is regulated exclusively by the army itself.[217]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Brazilian_Army

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk