A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

বিলাতী বাংলাদেশী | |

|---|---|

Distribution by local authority per 2011 census | |

| Total population | |

| 652,535[a] (2021/22)[1][2][3]

1.0% of the total UK population (2021/22) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Bengali · Sylheti[b] · English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam (92.0%); minority follows other faiths (1.5%)[c] or are irreligious (1.5%) 2021 census, England and Wales only[5] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Part of a series on |

| British people |

|---|

| United Kingdom |

| Eastern European |

| Northern European |

| Southern European |

| Western European |

| Central Asian |

| East Asian |

| South Asian |

| Southeast Asian |

| West Asian |

| African and Afro-Caribbean |

| Northern American |

| South American |

| Oceanian |

British Bangladeshis (Bengali: বিলাতী বাংলাদেশী, romanized: Bilatī Bangladeshī) are people of Bangladeshi origin who have attained citizenship in the United Kingdom, through immigration and historical naturalisation. The term can also refer to their descendants. Bengali Muslims have prominently been migrating to the UK since World War II. Migration reached its peak during the 1970s, with most originating from the Sylhet Division. The largest concentration live in east London boroughs, such as Tower Hamlets.[6][7] This large diaspora in London leads people in Sylhet to refer to British Bangladeshis as Londoni (Bengali: লন্ডনী).[6]

Bangladeshis form one of the UK's largest group of people of overseas descent and are also one of the country's youngest and fastest growing communities.[8] The 2021 United Kingdom census recorded over 652,500 Bangladeshis residing in the United Kingdom, with just under half of the population residing in Greater London.[1]

History

Bengalis have been present in Britain as early as the 19th century. One of the earliest records of a Bengali migrant, by the name of Saeed Ullah, can be found in Robert Lindsay's autobiography. Saeed Ullah was said to have migrated not only for work but also to attack Lindsay and avenge his elders for the Muharram Rebellion of 1782.[9] Other early records of arrivals from the region that is now known as Bangladesh are of Sylheti cooks in London during 1873, in the employment of the East India Company, who travelled to the UK as lascars on ships to work in restaurants.[10][11]

The first educated South Asian to travel to Europe and live in Britain was I'tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim cleric, Munshi and diplomat to the Mughal Empire who arrived in 1765 with his servant Muhammad Muqim during the reign of King George III.[12] He wrote of his experiences and travels in his Persian book, Shigurf-nama-i-Wilayat (or 'Wonder Book of Europe').[13] This is also the earliest record of literature by a British Asian. Also during the reign of George III, the hookah-bardar (hookah servant/preparer) of James Achilles Kirkpatrick was said to have robbed and cheated Kirkpatrick, making his way to England and stylising himself as the Prince of Sylhet. The man was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of the King.[14]

Many Sylheti people believed that seafaring was a historical and cultural inheritance due to a large proportion of Sylheti Muslims being descended from foreign traders, lascars and businessman from the Middle East and Central Asia who migrated to the Sylhet region before and after the Conquest of Sylhet.[15] Khala Miah, who was a Sylheti migrant, claimed this was a very encouraging factor for Sylhetis to travel to Calcutta aiming to eventually reach the United States and United Kingdom.[16] A crew of lascars would be led by a Serang. Serangs were ordered to recruit crew members themselves by the British and so they would go into their own villages and areas in the Sylhet region often recruiting their family and neighbours. The British had no problem with this as it guaranteed the group of lascars would be in harmony. According to lascars Moklis Miah and Mothosir Ali, up to forty lascars from the same village would be in the same ship.[15]

Shah Abdul Majid Qureshi claimed to be the first Sylheti to own a restaurant in the country. It was called Dilkush and was located in Soho.[17] Another one of his restaurants, known as India Centre, alongside early Sylheti migrant Ayub Ali Master's Shah Jalal cafe, became a hub for the British Asian community and a site where the India League would hold meetings attracting influential figures such as Subhas Chandra Bose, Krishna Menon and Mulk Raj Anand. Ayub Ali was also the president of the United Kingdom Muslim League having links with Liaquat Ali Khan and Mohammad Ali Jinnah.[18]

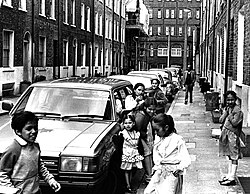

Some ancestors of British Bangladeshis went to the UK before the Second World War.[19] Author Caroline Adams records that in 1925 a lost Bengali man was searching for other Bengali settlers in London.[20] These first few arrivals started the process of "chain migration" mainly from one region of Bangladesh, Sylhet, which led to substantial numbers of people migrating from rural areas of the region, creating links between relatives in Britain and the region.[21] They mainly immigrated to the United Kingdom to find work, achieve a better standard of living, and to escape conflict. During the pre-state years, the 1950s and 1960s, Bengali men immigrated to London in search of employment.[20][22][23] Most settled in Tower Hamlets, particularly around Spitalfields and Brick Lane.[24] In 1971, Bangladesh (until then known as "East Pakistan") fought for its independence from West Pakistan in what was known as the Bangladesh Liberation War. In the region of Sylhet, this led some to join the Mukti Bahini, or Liberation Army.[25]

In the 1970s, changes in immigration laws encouraged a new wave of Bangladeshis to come to the UK and settle. Job opportunities were initially limited to low paid sectors, with unskilled and semi-skilled work in small factories and the textile trade being common. When the 'Indian' restaurant concept became popular, some Sylhetis started to open cafes. From these small beginnings a network of Bangladeshi restaurants, shops and other small businesses became established in Brick Lane and surrounding areas. The influence of Bangladeshi culture and diversity began to develop across the East London boroughs.[24]

The early immigrants lived and worked mainly in cramped basements and attics within the Tower Hamlets area. The men were often illiterate, poorly educated, and spoke little English, so they could not interact well with the English-speaking population and could not enter higher education.[22][26] Some became targets for businessmen, who sold their properties to Sylhetis, even though they had no legal claim to the buildings.[22][27]

By the late 1970s, the Brick Lane area had become predominantly Bengali, replacing the former Jewish community which had declined. Jews migrated to outlying suburbs of London, as they integrated with the majority British population. Jewish bakeries were turned into curry houses, jewellery shops became sari stores, and synagogues became dress factories. The synagogue at the corner of Fournier Street and Brick Lane became the Brick Lane Jamme Masjid or 'Brick Lane Mosque', which continues to serve the Bangladeshi community to this day.[22][27][28] This building represents the history of successive communities of immigrants in this part of London. It was built in 1743 as a French Protestant church; in 1819 it became a Methodist chapel, and in 1898 was designated as the Spitalfields Great Synagogue. It was finally sold, to become the Jamme Masjid.[29]

The period also however saw a rise in the number of attacks on Bangladeshis in the area, in a reprise of the racial tensions of the 1930s, when Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts had marched against the Jewish communities. In nearby Bethnal Green the anti-immigrant National Front became active, distributing leaflets on the streets and holding meetings. White youths known as "skinheads" appeared in the Brick Lane area, vandalising property and reportedly spitting on Bengali children and assaulting women. Bengali children were allowed out of school early; women walked to work in groups to shield them from potential violence. Parents began to impose curfews on their children, for their own safety; flats were protected against racially motivated arson by the installation of fire-proof letterboxes.[22]

On 4 May 1978, Altab Ali, a 24-year-old Bangladeshi leather clothing worker, was murdered by three teenage boys as he walked home from work in a racially motivated attack.[30] The murder took place near the corner of Adler Street and Whitechapel Road, by St Mary's Churchyard.[22][27] This murder mobilised the Bangladeshi community in Britain. Demonstrations were held in the area of Brick Lane against the National Front,[31] and groups such as the Bangladesh Youth Movement were formed. On 14 May, over 7,000-10,000 people, mostly Bangladeshis, took part in a demonstration against racial violence, marching behind Altab Ali's coffin to Hyde Park.[32][33][34] Some youths formed local gangs and carried out reprisal attacks on their skinhead opponents (see Youth gangs).

The name "Altab Ali" became associated with a movement of resistance against racist attacks, and remains linked with this struggle for human rights. His murder was the trigger for the first significant political organisation against racism by local Bangladeshis. The identification and association of British Bangladeshis with Tower Hamlets owes much to this campaign. A park has been named after Altab Ali at the street where he was murdered.[31] In 1993, racial violence was incited by the anti-immigration British National Party (BNP); several Bangladeshi students were severely injured, but the BNP's attempted inroads were stopped after demonstrations of Bangladeshi resolve.[22][35]

In 1986, the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee's race relations and immigration sub-committee conducted an inquiry called Bangladeshis in Britain. In evidence given to the committee by Home Office officials, they noted that an estimated 100,000 Bangladeshis lived in Great Britain. The evidence also noted issues of concern to the Bangladesh community, including "immigration arrangements; relationships with the police (particularly in the context of racial harassment or attacks); and the provision of suitable housing, education, and personal, health and social services". A Home Office official noted that the Sylheti dialect was "the ordinary means of communication for about 95 per cent of the people who come from Bangladesh" and that all three Bengali interpreters employed at Heathrow Airport spoke Sylheti, including Abdul Latif.[36]

In 1988, a "friendship link" between the city of St Albans in Hertfordshire and the municipality of Sylhet was created by the district council under the presidency of Muhammad Gulzar Hussain of Bangladesh Welfare Association, St Albans. BWA St Albans were able to name a road in Sylhet municipality (now Sylhet City Corporation) called St Albans Road. This link between the two cities was established when the council supported housing project in the city as part of the International Year of Shelter for the Homeless initiative. It was also created because Sylhet is the area of origin for the largest ethnic minority group in St Albans.[37][38] In April 2001, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets council officially renamed the 'Spitalfields' electoral ward Spitalfields and Banglatown. Surrounding streets were redecorated, with lamp posts painted in green and red, the colours of the Bangladeshi flag.[6] By this stage the majority living in the ward were of Bangladeshi origin—nearly 60% of the population.[26]

Demographics

| Region / Country | 2021[40] | 2011[44] | 2001[48] | 1991[51] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 629,583 | 1.11% | 436,514 | 0.82% | 275,394 | 0.56% | 157,881 | 0.34% | |

| —Greater London | 322,054 | 3.66% | 222,127 | 2.72% | 153,893 | 2.15% | 85,738 | 1.28% |

| —West Midlands | 77,518 | 1.30% | 52,477 | 0.94% | 31,401 | 0.60% | 19,415 | 0.38% |

| —North West | 60,859 | 0.82% | 45,897 | 0.65% | 26,003 | 0.39% | 15,016 | 0.22% |

| —East of England | 50,685 | 0.80% | 32,992 | 0.56% | 18,503 | 0.34% | 10,934 | 0.22% |

| —South East | 39,881 | 0.43% | 27,951 | 0.32% | 15,358 | 0.19% | 8,546 | 0.11% |

| —Yorkshire and the Humber | 29,018 | 0.53% | 22,424 | 0.42% | 12,330 | 0.25% | 8,347 | 0.17% |

| —East Midlands | 20,980 | 0.43% | 13,258 | 0.29% | 6,923 | 0.17% | 4,161 | 0.11% |

| —North East | 16,355 | 0.61% | 10,972 | 0.42% | 6,167 | 0.25% | 3,416 | 0.13% |

| —South West | 12,217 | 0.21% | 8,416 | 0.16% | 4,816 | 0.10% | 2,308 | 0.05% |

| 15,317 | 0.49% | 10,687 | 0.35% | 5,436 | 0.19% | 3,820 | 0.13% | |

| 6,934[α] | 0.12% | 3,788 | 0.07% | 1,981 | 0.04% | 1,134 | 0.02% | |

| Northern Ireland | 710 | 0.04% | 540 | 0.03% | 252 | 0.01% | — | — |

| 652,535 | 0.97% | 451,529 | 0.71% | 283,063 | 0.42% | 162,835[β] | 0.30% | |

Population

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk