A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Slovenes |

|---|

|

| Diaspora by country |

| Culture of Slovenia |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

Carinthian Slovenes or Carinthian Slovenians (Slovene: Koroški Slovenci; German: Kärntner Slowenen) are the indigenous minority of Slovene ethnicity, living within borders of the Austrian state of Carinthia, neighboring Slovenia. Their status of the minority group is guaranteed in principle by the Constitution of Austria and under international law, and have seats in the National Ethnic Groups Advisory Council.

History

The present-day Slovene-speaking area was initially settled towards the end of the early medieval Migration Period by, among others, the West Slavic peoples, and thereafter eventually by the South Slavs, who became the predominant group (see Slavic settlement of Eastern Alps). A South Slavic informal language with western Slavonic influence arose. At the end of the migration period, a Slavic proto-state called Carantania, the precursor of the later Duchy of Carinthia, arose; it extended far beyond the present area of the present state and its political center is said to have lain in the Zollfeld Valley.

In the mid 8th century, the Carantanian Prince Boruth, embattled by the Avars, had to pledge allegiance to Duke Odilo of Bavaria. The principality became part of Francia and the Carolingian Empire under Emperor Charlemagne, and, in consequence, was incorporated as the Carinthian march of the Holy Roman Empire. As a result of this, German noble families became gradually prevalent, while the rural population remained Slavic.[citation needed]

Finally, Bavarian settlers moved into Carinthia, where they established themselves in the hitherto sparsely populated areas, such as wooded regions and high valleys. Only here and there did this lead to the direct displacement of Slavs (the development of the Slovene nation did not take place until later). A language border formed which kept steady until the 19th century.[1] The local capital Klagenfurt, at this time a bilingual city with social superior German usage and Slovene-speaking environs, was also a centre of Slovene culture and literature.

Carinthian Plebiscite

With the emergence of the nationalist movement in the late Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, there was an acceleration in the process of assimilation; at the same time the conflict between national groups became more intense.

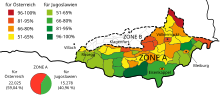

In the course of the dissolution of Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I, the Carinthian provisional assembly proclaimed the accession to German-Austria, whereafter the newly established State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs for a short time occupied the districts where the greater majority still used Slovene. Armed clashes followed and this issue also split the Slovene population. In the plebiscite zone in which the Slovene-speaking proportion of the population constituted about 70%, 59% of those who voted came out to remain with the First Austrian Republic. In the run-up to the plebiscite the state government gave an assurance that it would promote and support the retention of Slovene culture. These conciliatory promises, in addition to economic and other reasons, led to about 40% of the Slovenes living in the plebiscite zone voting to retain the unity of Carinthia. Voting patterns were, however, different by region; in many municipalities there were majorities who voted to become part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (mainly in the south).

Initially, the Slovene community in Carinthia enjoyed minority rights like bilingual schools and parishes, Slovene newspapers, associations and representatives in municipal councils and in the Landtag assembly.

Interwar Period

Similar to other European states, German nationalism in Austria grew in the interwar period and ethnic tensions led to an increasing discrimination against Carinthian Slovenes. Promises made were broken, assimilation was forced by dividing the Carinthian Slovenes into "nationalist" Slovenes proper and "Germanophile" Windisch, even by denying that their language – a Slovene dialect with a large number of words borrowed from German – was Slovene at all.

Nazi persecution and anti-Nazi resistance during World War II

The persecution increased with the 1938 Anschluss and escalated in 1942, when Slovene families were systematically expelled from their farms and homes and many were also sent to Nazi concentration camps, such as Ravensbrück, where the multiple-awarded writer Maja Haderlap's Grandmother was sent to.[2]

Following the Nazi persecution, Slovene minority members – including the awarded writer Maja Haderlap's grandfather and father – joined the only Anti-Nazi military resistance of Austria, i.e. Slovene Partisans. Many returned to Carinthia, including its capital Klagenfurt, as part of Yugoslav Partisans. Families whose members were fighting against Nazis as resistance fighters, were treated as 'homeland traitors' by the Austrian German-speaking neighbors, as described by Maja Haderlap,[2] after the WWII when they were forced by the British to withdraw from Austria.

Austrian State Treaty

As the Nazi rule had strongy reinforced the stigmatization of Slovene language and culture, anti-Slovene sentiments continued after WWII amongst large swaths of the German-speaking population in Carinthia.[3]

On 15 May 1955, the Austrian State Treaty was signed, in Article 7 of which the "rights of the Slovene and Croat minorities" in Austria were regulated. In 1975, the electoral grouping of the Slovene national group (Unity List) only just failed to gain entry to the state assembly. With the argument that in elections the population should vote for the political parties rather than according to their ethnic allegiance, before the next elections in 1979 the originally single electoral district of Carinthia was divided into four constituencies. The area of settlement of Carinthian Slovenes was divided up and these parts were in turn combined with purely German-speaking parts of the province. In the new constituencies, the Slovene-speaking proportion of the population was reduced in such a way that it was no longer possible for the representatives of national minorities to succeed in getting into the state assembly. The Austrian Center for Ethnic Groups and the representatives of Carinthian Slovenes saw in this way of proceeding a successful attempt of gerrymandering in order to reduce the political influence of the Slovene-speaking minority group.

In 1957, the German national Kärntner Heimatdienst (KHD) pressure group was established, by its own admission in order to advocate the interests of "patriotic" Carinthians. In the 1970s, the situation again escalated in a dispute over bilingual place-name signs (Ortstafelstreit), but thereafter became less tense.[4] However, continuing up to the present, individual statements by Slovene politicians are interpreted by parts of the German-speaking population as Slovene territorial claims, and they therefore regard the territorial integrity of Carinthia as still not being guaranteed.[citation needed] This interpretation is rejected both by the Slovene government and by the organizations representing the interests of Carinthian Slovenes. The territorial integrity of Carinthia and its remaining part of Austria are said not to be placed in question at all.

Current developments

Since the 1990s, a growing interest in Slovene on the part of the German-speaking Carinthians has been perceptible, but this could turn out to be too late in view of the increase in the proportion of elderly people. From 1997, Slovene and German traditionalist associations met in regular roundtable discussions to reach a consensus. However, the success of Jörg Haider, former governor of Carinthia from 1999 to 2008, in making again a political issue out of the dispute over bilingual place-name signs showed that the conflict is, as before, still present.[citation needed]

Area of Slovene settlement and proportion of the population

|

| 2001 census |

5–10% 10–20% 20–30% > 30%

|

|

| 1971 census |

At the end of the 19th century, Carinthian Slovenes comprised approximately one quarter to one third of the total population of Carinthia, which then, however, included parts that in the meantime have been ceded. In the course of the 20th century, the numbers declined, especially because of the pressure to assimilate, to an official figure of 2.3% of the total population. As the pressure from German came above all from the west and north, the present area of settlement lies in the south and east of the state, in the valleys known in German as Jauntal (Slovene: Podjuna), Rosental (Slovene: Rož), the lower Lavanttal (Labotska dolina), the Sattniz (Gure) mountains between the Drau River and Klagenfurt, and the lower part of Gailtal / Ziljska dolina (to about as far as Tröpolach). Köstenberg and Diex are approximately the most northerly points of current Slovene settlement. The municipalities with the highest proportion of Carinthian Slovenes are Zell (89%), Globasnitz (42%), and Eisenkappel-Vellach (38%), according to the 2001 special census which inquired about the mother tongue and preferred language. The actual number of Carinthian Slovenes is disputed, as both the representatives of Slovene organizations and the representatives of Carinthian traditional organizations describe the census results as inaccurate. The former point to the, in part, strongly fluctuating census results in individual municipalities, which in their opinion correlate strongly with political tensions in national minority questions. Consequently, the results would underestimate the actual number of Carinthian Slovenes.[citation needed] The South Carinthian municipality of Gallizien is cited as an example: according to the 1951 census the proportion of Slovene speakers was 80%, whereas in 1961—in absence of any significant migratory movements and with approximately the same population—the proportion dropped to only 11%.

| Year | Number of Slovenes |

|---|---|

| 1818 | 137,000 |

| 1848 | 114,000 |

| 1880 | 85,051 |

| 1890 | 84,667 |

| 1900 | 75,136 |

| 1910 | 66,463 |

| 1923 | 34,650 |

| 1934 | 24,875 |

| 1939 | 43,179 |

| 1951 | 42,095 |

| 1961 | 24,911 |

| 1971 | 20,972 |

| 1981 | 16,552 |

| 1991 | 14,850 |

| 2001 | 13,109 |

As a further example, the results of the former municipality of Mieger (now in the municipality of Ebental) are cited, which in 1910 and 1923 had a Slovene-speaking population of 96% and 51% respectively, but in 1934 only 3%. After World War II and a relaxation of relations between both population groups, the municipality showed a result of 91.5% in the 1951 census. Ultimately, in 1971 in the run-up to the Carinthian place-name signs dispute, the number of the Slovenes was reduced again to 24%. The representatives of Carinthian Slovenes regard the census results as the absolute lower limit. They refer to an investigation carried out in 1991 in bilingual parishes, in the process of which there was a question about the colloquial language used by members of the parish. The results of this investigation (50,000 members of national minority groups) differed significantly from those of the census that took place in the same year (about 14,000). Carinthian traditional organizations, on the other hand, estimate the actual number of self-declared Slovenes as being 2,000 to 5,000 persons.

| Municipalities | Percent of Slovenes 2001 | Percent of Slovenes 1951 | Percent of Slovenes 1880 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg/Brdo | Part of Hermagor/Šmohor | 56.1% | 95% |

| Görtschach/Goriče | Part of Hermagor/Šmohor | 58.4% | 98.5% |

| St. Stefan im Gailtal/Štefan na Zilji | 1.2% | N.D. | 97.4% |

| Vorderberg/Blače | Part of St. Stefan im Gailtal/Štefan na Zilji | 54.8% | 99.8% |

| Hermagor/Šmohor | 1.6% | N.D | N.D |

| Arnoldstein/Podklošter | 2.1% | 9.2% | 39.7% |

| Augsdorf/Loga vas | Part of Velden am Wörther See/Vrba ob Jezeru | 48.2% | 93.8% |

| Feistritz an der Gail/Bistrica na Zilji | 7.9% | 53.4% | 83.9% |

| Finkenstein/Bekštanj | 5.7% | 24.2% | 96.3% |

| Hohenthurn/Straja vas | 8.3 | 27.1% | 98.9% |

| Köstenberg/Kostanje | Part of Velden am Wörther See/Vrba | 40.1% | 76.1% |

| Ledenitzen/Ledince | Part of Sankt Jakob im Rosental/Šentjakob v Rožu | 37.8% | 96.8% |

| Lind ob Velden/Lipa pri Vrbi | Part of Velden am Wörther See/Vrba | 15.8% | 44.5% |

| Maria Gail/Marija na Zilji | Part of Villach/Beljak | 16.7% | 95.9% |

| Nötsch/Čajna | 0.6% | 3.6% | N.D. |

| Rosegg/Rožek | 6.1% | 32.4% | 96.7% |

| Sankt Jakob im Rosental/Št. Jakob v Rožu | 16.4% | 62.7% | 99.3% |

| Velden am Wörther See/Vrba ob Jezeru | 2.8% | 0.9% | 96.3% |

| Wernberg/Vernberk | 1.0% | 20.5% | 73.2% |

| Ebental/Žrelec | 4.2% | 16.4% | 62.8% |

| Feistritz im Rosental/Bistrica v Rožu | 13.4% | 47.2% | 97.7% |

| Ferlach/Borovlje | 8.3% | 20.5% | 61.4% |

| Grafenstein/Grabštajn | 0.8% | 7.6% | 95.6% |

| Keutschach/Hodiše | 5.6% | 60.6% | 96.5% |

| Köttmannsdorf/Kotmara vas | 6.4% | 45.6% | 95.3% |

| Ludmannsdorf/Bilčovs | 28.3% | 85.0% | 100% |

| Maria Rain/Žihpolje | 3.9% | 10.5% | 55.1% |

| Maria Wörth/Otok | 1.1% | 16.3% | 41.9% |

| Mieger/Medgorje | Part of Ebental/Žrelec | 91.5% | 98.1% |

| Poggersdorf/Pokrče | 1.2% | 2.8% | 87% |

| Radsberg/Radiše | Part of Ebental/Žrelec | 52.0% | 100% |

| Schiefling/Škofiče | 6.0% | 38.4% | 98.9% |

| Sankt Margareten im Rosental/ Šmarjeta v Rožu | 11.8% | 76.8% | 92.4% |

| Magdalensberg/Štalenska gora | 1.5% | 3.1% | N.D. |

| Techelsberg/Teholica | 0.2% | 6.7% | N.D. |

| Unterferlach/Medborovnica | Part of Ferlach/Borovlje | 47.2% | 99.7% |

| Viktring/Vetrinj | Part of Klagenfurt/Celovec | 3.3% | 57.6% |

| Weizelsdorf/Svetna vas | Part of Feistritz im Rosental/Bistrica v Rožu | 69.3% | 100% |

| Windisch Bleiberg/Slovenji Plajberk | Part of Ferlach/Borovlje | 81.3% | 91.7% |

| Zell/Sele | 89.6% | 93.1% | 100% |

| Feistritz ob Bleiburg/Bistrica pri Pliberku | 33.2% | 82.8% | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Carinthian_Slovenes