A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Cleveland Guardians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

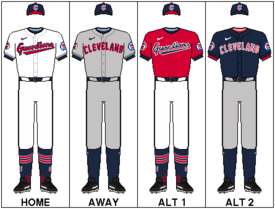

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| |||||

| Name | |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (2) | |||||

| AL Pennants (6) | |||||

| AL Central Division titles (11) | |||||

| Wild card berths (2) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Larry Dolan | ||||

| President | Paul Dolan (Chairman / CEO) | ||||

| President of baseball operations | Chris Antonetti | ||||

| General manager | Mike Chernoff | ||||

| Manager | Stephen Vogt | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/guardians | ||||

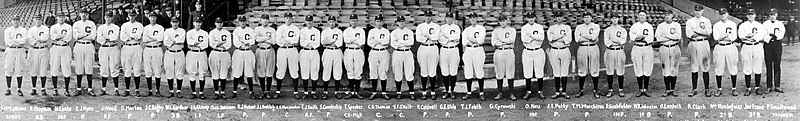

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central Division. Since 1994, the team has played its home games at Progressive Field. Since their establishment as a Major League franchise in 1901, the team has won 11 Central Division titles, six American League pennants, and two World Series championships (in 1920 and 1948). The team's World Series championship drought since 1948 is the longest active among all 30 current Major League teams.[1] The team's name references the Guardians of Traffic, eight monolithic 1932 Art Deco sculptures by Henry Hering on the city's Hope Memorial Bridge,[2] which is adjacent to Progressive Field.[3][4] The team's mascot is named "Slider".[5] The team's spring training facility is at Goodyear Ballpark in Goodyear, Arizona.[6]

The franchise originated in 1896 as the Columbus Buckeyes, a minor league team based in Columbus, Ohio, that played in the Western League.[7] The team renamed to the Columbus Senators the following year and then relocated to Grand Rapids, Michigan in the middle of the 1899 season, becoming the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers for the remainder of the season.[8][9] The team relocated to Cleveland in 1900 and was called the Cleveland Lake Shores.[10] The Western League itself was renamed the American League prior to the 1900 season while continuing its minor league status. When the American League declared itself a major league in 1901, Cleveland was one of its eight charter franchises. Originally called the Cleveland Bluebirds or Blues, the team was also unofficially called the Cleveland Bronchos in 1902. Beginning in 1903, the team was named the Cleveland Napoleons or Naps, after team captain Nap Lajoie.

Lajoie left after the 1914 season and club owner Charles Somers requested that baseball writers choose a new name. They chose the name Cleveland Indians.[11][12] That name stuck and remained in use for more than a century. Common nicknames for the Indians were "the Tribe" and "the Wahoos", the latter referencing their longtime logo, Chief Wahoo. After the Indians name came under criticism as part of the Native American mascot controversy, the team adopted the Guardians name following the 2021 season.[3][13][14][15][16]

From August 24 to September 14, 2017, the team won 22 consecutive games, the longest winning streak in American League history, and the second longest winning streak in Major League Baseball history.

As of the end of the 2023 season, the franchise's overall record is 9,760–9,300 (.512).[17]

Early Cleveland baseball teams

According to one historian of baseball, "In 1857, baseball games were a daily spectacle in Cleveland's Public Squares. City authorities tried to find an ordinance forbidding it, to the joy of the crowd, they were unsuccessful."[18]

- 1865–1868 Forest Citys of Cleveland (Amateur)

- 1869–1872 Forest Citys of Cleveland

From 1865 to 1868 Forest Citys was an amateur ball club. During the 1869 season, Cleveland was among several cities that established professional baseball teams following the success of the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first fully professional team.[19][20] In the newspapers before and after 1870, the team was often called the Forest Citys, in the same generic way that the team from Chicago was sometimes called The Chicagos.

In 1871 the Forest Citys joined the new National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NA), the first professional league. Ultimately, two of the league's western clubs went out of business during the first season and the Chicago Fire left that city's White Stockings impoverished, unable to field a team again until 1874. Cleveland was thus the NA's westernmost outpost in 1872, the year the club folded. Cleveland played its full schedule to July 19 followed by two games versus Boston in mid-August and disbanded at the end of the season.[21]

- 1879–1881 Cleveland Forest Citys

- 1882–1884 Cleveland Blues

In 1876, the National League (NL) supplanted the NA as the major professional league. Cleveland was not among its charter members, but by 1879 the league was looking for new entries and the city gained an NL team. The Cleveland Forest Citys were recreated, but rebranded in 1882 as the Cleveland Blues, because the National League required distinct colors for that season. The Blues had mediocre records for six seasons and were ruined by a trade war with the Union Association (UA) in 1884, when its three best players (Fred Dunlap, Jack Glasscock, and Jim McCormick) jumped to the UA after being offered higher salaries. The Cleveland Blues merged with the St. Louis Maroons UA team in 1885.

- 1887–1899 Cleveland Spiders – nickname "Blues"

Cleveland went without major league baseball for two seasons until gaining a team in the American Association (AA) in 1887. After the AA's Allegheny club jumped to the NL, Cleveland followed suit in 1889, as the AA began to crumble. The Cleveland ball club, named the Spiders (supposedly inspired by their "skinny and spindly" players) slowly became a power in the league.[22] In 1891, the Spiders moved into League Park, which would serve as the home of Cleveland professional baseball for the next 55 years. Led by native Ohioan Cy Young, the Spiders became a contender in the mid-1890s, playing in the Temple Cup Series (that era's World Series) twice and winning it in 1895. The team began to fade after this success, and was dealt a severe blow under the ownership of the Robison brothers.

Prior to the 1899 season, Frank Robison, the Spiders' owner, bought the St. Louis Browns, thus owning two clubs at the same time. The Browns were renamed the "Perfectos", and restocked with Cleveland talent. Just weeks before the season opener, most of the better Spiders were transferred to St. Louis, including three future Hall of Famers: Cy Young, Jesse Burkett and Bobby Wallace.[23] The roster maneuvers failed to create a powerhouse Perfectos team, as St. Louis finished fifth in both 1899 and 1900. The Spiders were left with essentially a minor league lineup, and began to lose games at a record pace. Drawing almost no fans at home, they ended up playing most of their season on the road, and became known as "The Wanderers".[24] The team ended the season in 12th place, 84 games out of first place, with an all-time worst record of 20–134 (.130 winning percentage).[25] Following the 1899 season, the National League disbanded four teams, including the Spiders franchise. The disastrous 1899 season would actually be a step toward a new future for Cleveland fans the next year.

- 1890, Cleveland Infants – nickname "Babes"

The Cleveland Infants competed in the Players' League, which was well-attended in some cities, but club owners lacked the confidence to continue beyond the one season. The Cleveland Infants finished with 55 wins and 75 losses, playing their home games at Brotherhood Park.[26]

Franchise history

1896–1935: Beginning to middle

The Columbus Buckeyes were founded in Ohio in 1896 and were part of the Western League.[7] In 1897 the team changed their name to the Columbus Senators.[8] In the middle of the 1899 season, the Senators made a swap with the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers of the Interstate League; the Columbus Senators would become the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers and play in the Western League, and the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers would become the Columbus Senators and play in the Interstate League.[27] Often confused with the Grand Rapids Rustlers (also known as Rippers), the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers finished the 1899 season in the Western League to become the Grand Rapids franchise to be relocated to Cleveland the following season.[9][28] In 1900 the team moved to Cleveland and was named the Cleveland Lake Shores. Around the same time Ban Johnson changed the name of his minor league (Western League) to the American League. In 1900 the American League was still considered a minor league. In 1901 the team was called the Cleveland Bluebirds or Blues when the American League broke with the National Agreement and declared itself a competing Major League. The Cleveland franchise was among its eight charter members, and is one of four teams that remain in its original city, along with Boston, Chicago, and Detroit.

The new team was owned by coal magnate Charles Somers and tailor Jack Kilfoyl. Somers, a wealthy industrialist and also co-owner of the Boston Americans, lent money to other team owners, including Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics, to keep them and the new league afloat. Players did not think the name "Bluebirds" was suitable for a baseball team.[29] Writers frequently shortened it to Cleveland Blues due to the players' all-blue uniforms,[30] but the players did not like this unofficial name either.[31] The players themselves tried to change the name to Cleveland Bronchos in 1902, but this name never caught on.[29]

Cleveland suffered from financial problems in their first two seasons. This led Somers to seriously consider moving to either Pittsburgh or Cincinnati. Relief came in 1902 as a result of the conflict between the National and American Leagues. In 1901, Napoleon "Nap" Lajoie, the Philadelphia Phillies' star second baseman, jumped to the A's after his contract was capped at $2,400 per year—one of the highest-profile players to jump to the upstart AL. The Phillies subsequently filed an injunction to force Lajoie's return, which was granted by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The injunction appeared to doom any hopes of an early settlement between the warring leagues. However, a lawyer discovered that the injunction was only enforceable in the state of Pennsylvania.[29] Mack, partly to thank Somers for his past financial support, agreed to trade Lajoie to the then-moribund Blues, who offered $25,000 salary over three years.[32] Due to the injunction, however, Lajoie had to sit out any games played against the A's in Philadelphia.[33] Lajoie arrived in Cleveland on June 4 and was an immediate hit, drawing 10,000 fans to League Park. Soon afterward, he was named team captain, and in 1903 the team was called the Cleveland Napoleons or Naps after a newspaper conducted a write-in contest.[29]

Lajoie was named manager in 1905, and the team's fortunes improved somewhat. They finished half a game short of the pennant in 1908.[34] However, the success did not last and Lajoie resigned during the 1909 season as manager but remained on as a player.[35]

After that, the team began to unravel, leading Kilfoyl to sell his share of the team to Somers. Cy Young, who returned to Cleveland in 1909, was ineffective for most of his three remaining years[36] and Addie Joss died from tubercular meningitis prior to the 1911 season.[37]

Despite a strong lineup anchored by the potent Lajoie and Shoeless Joe Jackson, poor pitching kept the team below third place for most of the next decade. One reporter referred to the team as the Napkins, "because they fold up so easily". The team hit bottom in 1914 and 1915, finishing last place both years.[38][39]

1915 brought significant changes to the team. Lajoie, nearly 40 years old, was no longer a top hitter in the league, batting only .258 in 1914. With Lajoie engaged in a feud with manager Joe Birmingham, the team sold Lajoie back to the A's.[40]

With Lajoie gone, the club needed a new name. Somers asked the local baseball writers to come up with a new name, and based on their input, the team was renamed the Cleveland Indians.[41] The name referred to the nickname "Indians" that was applied to the Cleveland Spiders baseball club during the time when Louis Sockalexis, a Native American, played in Cleveland (1897–1899).[42]

At the same time, Somers' business ventures began to fail, leaving him deeply in debt. With the Indians playing poorly, attendance and revenue suffered.[43] Somers decided to trade Jackson midway through the 1915 season for two players and $31,500, one of the largest sums paid for a player at the time.[44]

By 1916, Somers was at the end of his tether, and sold the team to a syndicate headed by Chicago railroad contractor James C. "Jack" Dunn.[43] Manager Lee Fohl, who had taken over in early 1915, acquired two minor league pitchers, Stan Coveleski and Jim Bagby and traded for center fielder Tris Speaker, who was engaged in a salary dispute with the Red Sox.[45] All three would ultimately become key players in bringing a championship to Cleveland.

Speaker took over the reins as player-manager in 1919, and led the team to a championship in 1920. On August 16, 1920, the Indians were playing the Yankees at the Polo Grounds in New York. Shortstop Ray Chapman, who often crowded the plate, was batting against Carl Mays, who had an unusual underhand delivery. It was also late in the afternoon and the infield was completely shaded with the center field area (the batters' background) bathed in sunlight. As well, at the time, "part of every pitcher's job was to dirty up a new ball the moment it was thrown onto the field. By turns, they smeared it with dirt, licorice, tobacco juice; it was deliberately scuffed, sandpapered, scarred, cut, even spiked. The result was a misshapen, earth-colored ball that traveled through the air erratically, tended to soften in the later innings, and as it came over the plate, was very hard to see."[46]

In any case, Chapman did not move reflexively when Mays' pitch came his way. The pitch hit Chapman in the head, fracturing his skull. Chapman died the next day, becoming the only player to sustain a fatal injury from a pitched ball.[47] The Indians, who at the time were locked in a tight three-way pennant race with the Yankees and White Sox,[48] were not slowed down by the death of their teammate. Rookie Joe Sewell hit .329 after replacing Chapman in the lineup.[49]

In September 1920, the Black Sox Scandal came to a boil. With just a few games left in the season, and Cleveland and Chicago neck-and-neck for first place at 94–54 and 95–56 respectively,[50][51] the Chicago owner suspended eight players. The White Sox lost two of three in their final series, while Cleveland won four and lost two in their final two series. Cleveland finished two games ahead of Chicago and three games ahead of the Yankees to win its first pennant, led by Speaker's .388 hitting, Jim Bagby's 30 victories and solid performances from Steve O'Neill and Stan Coveleski. Cleveland went on to defeat the Brooklyn Robins 5–2 in the World Series for their first title, winning four games in a row after the Robins took a 2–1 Series lead. The Series included three memorable "firsts", all of them in Game 5 at Cleveland, and all by the home team. In the first inning, right fielder Elmer Smith hit the first Series grand slam. In the fourth inning, Jim Bagby hit the first Series home run by a pitcher. In the top of the fifth inning, second baseman Bill Wambsganss executed the first (and only, so far) unassisted triple play in World Series history, in fact, the only Series triple play of any kind.

The team would not reach the heights of 1920 again for 28 years. Speaker and Coveleski were aging and the Yankees were rising with a new weapon: Babe Ruth and the home run. They managed two second-place finishes but spent much of the decade in last place. In 1927 Dunn's widow, Mrs. George Pross (Dunn had died in 1922), sold the team to a syndicate headed by Alva Bradley.

1936–1946: Bob Feller enters the show

The Indians were a middling team by the 1930s, finishing third or fourth most years. 1936 brought Cleveland a new superstar in 17-year-old pitcher Bob Feller, who came from Iowa with a dominating fastball. That season, Feller set a record with 17 strikeouts in a single game and went on to lead the league in strikeouts from 1938 to 1941.

On August 20, 1938, Indians catchers Hank Helf and Frank Pytlak set the "all-time altitude mark" by catching baseballs dropped from the 708-foot (216 m) Terminal Tower.[52]

By 1940, Feller, along with Ken Keltner, Mel Harder and Lou Boudreau, led the Indians to within one game of the pennant. However, the team was wracked with dissension, with some players (including Feller and Mel Harder) going so far as to request that Bradley fire manager Ossie Vitt. Reporters lampooned them as the Cleveland Crybabies.[53][better source needed] Feller, who had pitched a no-hitter to open the season and won 27 games, lost the final game of the season to unknown pitcher Floyd Giebell of the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers won the pennant and Giebell never won another major league game.[54]

Cleveland entered 1941 with a young team and a new manager; Roger Peckinpaugh had replaced the despised Vitt; but the team regressed, finishing in fourth. Cleveland would soon be depleted of two stars. Hal Trosky retired in 1941 due to migraine headaches[55] and Bob Feller enlisted in the Navy two days after the Attack on Pearl Harbor. Starting third baseman Ken Keltner and outfielder Ray Mack were both drafted in 1945 taking two more starters out of the lineup.[56]

1946–1949: The Bill Veeck years

In 1946, Bill Veeck formed an investment group that purchased the Cleveland Indians from Bradley's group for a reported $1.6 million.[57] Among the investors was Bob Hope, who had grown up in Cleveland, and former Tigers slugger, Hank Greenberg.[58] A former owner of a minor league franchise in Milwaukee, Veeck brought to Cleveland a gift for promotion. At one point, Veeck hired rubber-faced[59] Max Patkin, the "Clown Prince of Baseball" as a coach. Patkin's appearance in the coaching box was the sort of promotional stunt that delighted fans but infuriated the American League front office.

Recognizing that he had acquired a solid team, Veeck soon abandoned the aging, small and lightless League Park to take up full-time residence in massive Cleveland Municipal Stadium.[60] The Indians had briefly moved from League Park to Municipal Stadium in mid-1932, but moved back to League Park due to complaints about the cavernous environment. From 1937 onward, however, the Indians began playing an increasing number of games at Municipal, until by 1940 they played most of their home slate there.[61] League Park was mostly demolished in 1951, but has since been rebuilt as a recreational park.[62]

Making the most of the cavernous stadium, Veeck had a portable center field fence installed, which he could move in or out depending on how the distance favored the Indians against their opponents in a given series. The fence moved as much as 15 feet (5 m) between series opponents. Following the 1947 season, the American League countered with a rule change that fixed the distance of an outfield wall for the duration of a season. The massive stadium did, however, permit the Indians to set the then-record for the largest crowd to see a Major League baseball game. On October 10, 1948, Game 5 of the World Series against the Boston Braves drew over 84,000. The record stood until the Los Angeles Dodgers drew a crowd in excess of 92,500 to watch Game 5 of the 1959 World Series at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum against the Chicago White Sox.

Under Veeck's leadership, one of Cleveland's most significant achievements was breaking the color barrier in the American League by signing Larry Doby, formerly a player for the Negro league's Newark Eagles in 1947, 11 weeks after Jackie Robinson signed with the Dodgers.[60] Similar to Robinson, Doby battled racism on and off the field but posted a .301 batting average in 1948, his first full season. A power-hitting center fielder, Doby led the American League twice in homers.

In 1948, needing pitching for the stretch run of the pennant race, Veeck turned to the Negro leagues again and signed pitching great Satchel Paige amid much controversy.[60] Barred from Major League Baseball during his prime, Veeck's signing of the aging star in 1948 was viewed by many as another publicity stunt. At an official age of 42, Paige became the oldest rookie in Major League baseball history, and the first black pitcher. Paige ended the year with a 6–1 record with a 2.48 ERA, 45 strikeouts and two shutouts.[63]

In 1948, veterans Boudreau, Keltner, and Joe Gordon had career offensive seasons, while newcomers Doby and Gene Bearden also had standout seasons. The team went down to the wire with the Boston Red Sox, winning a one-game playoff, the first in American League history, to go to the World Series. In the series, the Indians defeated the Boston Braves four games to two for their first championship in 28 years. Boudreau won the American League MVP Award.

The Indians appeared in a film the following year titled The Kid From Cleveland, in which Veeck had an interest.[60] The film portrayed the team helping out a "troubled teenaged fan"[64] and featured many members of the Indians organization. However, filming during the season cost the players valuable rest days leading to fatigue towards the end of the season.[60] That season, Cleveland again contended before falling to third place. On September 23, 1949, Bill Veeck and the Indians buried their 1948 pennant in center field the day after they were mathematically eliminated from the pennant race.[60]

Later in 1949, Veeck's first wife (who had a half-stake in Veeck's share of the team) divorced him. With most of his money tied up in the Indians, Veeck was forced to sell the team[65] to a syndicate headed by insurance magnate Ellis Ryan.

1950–1959: Near misses

In 1953, Al Rosen was an All Star for the second year in a row, was named The Sporting News Major League Player of the Year, and won the American League Most Valuable Player Award in a unanimous vote playing for the Indians after leading the AL in runs, home runs, RBIs (for the second year in a row), and slugging percentage, and coming in second by one point in batting average.[66] Ryan was forced out in 1953 in favor of Myron Wilson, who in turn gave way to William Daley in 1956. Despite this turnover in the ownership, a powerhouse team composed of Feller, Doby, Minnie Miñoso, Luke Easter, Bobby Ávila, Al Rosen, Early Wynn, Bob Lemon, and Mike Garcia continued to contend through the early 1950s. However, Cleveland only won a single pennant in the decade, in 1954, finishing second to the New York Yankees five times.

The winningest season in franchise history came in 1954, when the Indians finished the season with a record of 111–43 (.721). That mark set an American League record for wins that stood for 44 years until the Yankees won 114 games in 1998 (a 162-game regular season). The Indians' 1954 winning percentage of .721 is still an American League record. The Indians returned to the World Series to face the New York Giants. The team could not bring home the title, however, ultimately being upset by the Giants in a sweep. The series was notable for Willie Mays' over-the-shoulder catch off the bat of Vic Wertz in Game 1. Cleveland remained a talented team throughout the remainder of the decade, finishing in second place in 1959, George Strickland's last full year in the majors.

1960–1993: The 33-year slump

From 1960 to 1993, the Indians managed one third-place finish (in 1968) and six fourth-place finishes (in 1960, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1990, and 1992) but spent the rest of the time at or near the bottom of the standings, including four seasons with over 100 losses (1971, 1985, 1987, 1991).

Frank Lane becomes general manager

The Indians hired general manager Frank Lane, known as "Trader" Lane, away from the St. Louis Cardinals in 1957. Lane over the years had gained a reputation as a GM who loved to make deals. With the White Sox, Lane had made over 100 trades involving over 400 players in seven years.[67] In a short stint in St. Louis, he traded away Red Schoendienst and Harvey Haddix.[67] Lane summed up his philosophy when he said that the only deals he regretted were the ones that he did not make.[68]

One of Lane's early trades in Cleveland was to send Roger Maris to the Kansas City Athletics in the middle of 1958. Indians executive Hank Greenberg was not happy about the trade[69] and neither was Maris, who said that he could not stand Lane.[69] After Maris broke Babe Ruth's home run record, Lane defended himself by saying he still would have done the deal because Maris was unknown and he received good ballplayers in exchange.[69]

After the Maris trade, Lane acquired 25-year-old Norm Cash from the White Sox for Minnie Miñoso and then traded him to Detroit before he ever played a game for the Indians; Cash went on to hit over 350 home runs for the Tigers. The Indians received Steve Demeter in the deal, who had only five at-bats for Cleveland.[70]

Curse of Rocky Colavito

In 1960, Lane made the trade that would define his tenure in Cleveland when he dealt slugging right fielder and fan favorite[71] Rocky Colavito to the Detroit Tigers for Harvey Kuenn just before Opening Day in 1960.

It was a blockbuster trade that swapped the 1959 AL home run co-champion (Colavito) for the AL batting champion (Kuenn). After the trade, however, Colavito hit over 30 home runs four times and made three All-Star teams for Detroit and Kansas City before returning to Cleveland in 1965. Kuenn, on the other hand, played only one season for the Indians before departing for San Francisco in a trade for an aging Johnny Antonelli and Willie Kirkland. Akron Beacon Journal columnist Terry Pluto documented the decades of woe that followed the trade in his book The Curse of Rocky Colavito.[72] Despite being attached to the curse, Colavito said that he never placed a curse on the Indians but that the trade was prompted by a salary dispute with Lane.[73]

Lane also engineered a unique trade of managers in mid-season 1960, sending Joe Gordon to the Tigers in exchange for Jimmy Dykes. Lane left the team in 1961, but ill-advised trades continued. In 1965, the Indians traded pitcher Tommy John, who would go on to win 288 games in his career, and 1966 Rookie of the Year Tommy Agee to the White Sox to get Colavito back.[73]

However, Indians' pitchers set numerous strikeout records. They led the league in K's every year from 1963 to 1968, and narrowly missed in 1969. The 1964 staff was the first to amass 1,100 strikeouts, and in 1968, they were the first to collect more strikeouts than hits allowed.

Move to the AL East division

The 1970s were not much better, with the Indians trading away several future stars, including Graig Nettles, Dennis Eckersley, Buddy Bell and 1971 Rookie of the Year Chris Chambliss,[74] for a number of players who made no impact.[75]

Constant ownership changes did not help the Indians. In 1963, Daley's syndicate sold the team to a group headed by general manager Gabe Paul.[29] Three years later, Paul sold the Indians to Vernon Stouffer,[76] of the Stouffer's frozen-food empire. Prior to Stouffer's purchase, the team was rumored to be relocated due to poor attendance. Despite the potential for a financially strong owner, Stouffer had some non-baseball related financial setbacks and, consequently, the team was cash-poor. In order to solve some financial problems, Stouffer had made an agreement to play a minimum of 30 home games in New Orleans with a view to a possible move there.[77] After rejecting an offer from George Steinbrenner and former Indian Al Rosen, Stouffer sold the team in 1972 to a group led by Cleveland Cavaliers and Cleveland Barons owner Nick Mileti.[77] Steinbrenner went on to buy the New York Yankees in 1973.[78]

Only five years later, Mileti's group sold the team for $11 million to a syndicate headed by trucking magnate Steve O'Neill and including former general manager and owner Gabe Paul.[79] O'Neill's death in 1983 led to the team going on the market once more. O'Neill's nephew Patrick O'Neill did not find a buyer until real estate magnates Richard and David Jacobs purchased the team in 1986.[80]

The team was unable to move out of last place, with losing seasons between 1969 and 1975. One highlight was the acquisition of Gaylord Perry in 1972. The Indians traded fireballer "Sudden Sam" McDowell for Perry, who became the first Indian pitcher to win the Cy Young Award. In 1975, Cleveland broke another color barrier with the hiring of Frank Robinson as Major League Baseball's first African American manager. Robinson served as player-manager and provided a franchise highlight when he hit a pinch-hit home run on Opening Day. But the high-profile signing of Wayne Garland, a 20-game winner in Baltimore, proved to be a disaster after Garland suffered from shoulder problems and went 28–48 over five years.[81] The team failed to improve with Robinson as manager and he was fired in 1977. In 1977, pitcher Dennis Eckersley threw a no-hitter against the California Angels. The next season, he was traded to the Boston Red Sox where he won 20 games in 1978 and another 17 in 1979.

The 1970s also featured the infamous Ten Cent Beer Night at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. The ill-conceived promotion at a 1974 game against the Texas Rangers ended in a riot by fans and a forfeit by the Indians.[82]

There were more bright spots in the 1980s. In May 1981, Len Barker threw a perfect game against the Toronto Blue Jays, joining Addie Joss as the only other Indian pitcher to do so.[83] "Super Joe" Charboneau won the American League Rookie of the Year award. Unfortunately, Charboneau was out of baseball by 1983 after falling victim to back injuries[84] and Barker, who was also hampered by injuries, never became a consistently dominant starting pitcher.[83]

Eventually, the Indians traded Barker to the Atlanta Braves for Brett Butler and Brook Jacoby,[83] who became mainstays of the team for the remainder of the decade. Butler and Jacoby were joined by Joe Carter, Mel Hall, Julio Franco and Cory Snyder, bringing new hope to fans in the late 1980s.[85]

Cleveland's struggles over the 30-year span were highlighted in the 1989 film Major League, which comically depicted a hapless Cleveland ball club going from worst to first by the end of the film.

Throughout the 1980s, the Indians' owners had pushed for a new stadium. Cleveland Stadium had been a symbol of the Indians' glory years in the 1940s and 1950s.[86] However, during the lean years even crowds of 40,000 were swallowed up by the cavernous environment. The old stadium was not aging gracefully; chunks of concrete were falling off in sections and the old wooden pilings were petrifying.[87] In 1984, a proposal for a $150 million domed stadium was defeated in a referendum 2–1.[88]

Finally, in May 1990, Cuyahoga County voters passed an excise tax on sales of alcohol and cigarettes in the county. The tax proceeds were to be used for financing the construction of the Gateway Sports and Entertainment Complex, which would include Jacobs Field for the Indians and Gund Arena for the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team.[89]

The team's fortunes started to turn in 1989, ironically with a very unpopular trade. The team sent power-hitting outfielder Joe Carter to the San Diego Padres for two unproven players, Sandy Alomar Jr. and Carlos Baerga. Alomar made an immediate impact, not only being elected to the All-Star team but also winning Cleveland's fourth Rookie of the Year award and a Gold Glove. Baerga became a three-time All-Star with consistent offensive production.

Indians general manager John Hart made a number of moves that finally brought success to the team. In 1991, he hired former Indian Mike Hargrove to manage and traded catcher Eddie Taubensee to the Houston Astros who, with a surplus of outfielders, were willing to part with Kenny Lofton. Lofton finished second in AL Rookie of the Year balloting with a .285 average and 66 stolen bases.

The Indians were named "Organization of the Year" by Baseball America[90] in 1992, in response to the appearance of offensive bright spots and an improving farm system.

The team suffered a tragedy during spring training of 1993, when a boat carrying pitchers Steve Olin, Tim Crews, and Bob Ojeda crashed into a pier. Olin and Crews were killed, and Ojeda was seriously injured. (Ojeda missed most of the season, and retired the following year).[91]

By the end of the 1993 season, the team was in transition, leaving Cleveland Stadium and fielding a talented nucleus of young players. Many of those players came from the Indians' new AAA farm team, the Charlotte Knights, who won the International League title that year.

1994–2001: New beginnings

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Cleveland_GuardiansText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk