A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Communist Party of the Soviet Union Коммунистическая партия Советского Союза | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leadership[a] | Yakov Sverdlov (first) Vladimir Ivashko (last) |

| Founder | Vladimir Lenin |

| Founded | 5 January 1912[b] |

| Banned | 6 November 1991[1] |

| Preceded by | Bolshevik faction of the RSDLP |

| Succeeded by | UCP–CPSU[2] |

| Headquarters | 4 Staraya Square, Moscow |

| Newspaper | Pravda[3] |

| Youth wing | Komsomol[4] |

| Pioneer wing | Little Octobrists, Young Pioneers[5] |

| Membership | 19,487,822 (1989 est.)[6] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-left[10][11] |

| Religion | None[12] |

| National affiliation | Bloc of Communists and Non-Partisans (1936–91)[13][14] |

| International affiliation | |

| Colours | Red[18] |

| Slogan | "Workers of the world, unite!"[c] |

| Anthem | "The Internationale"[d][19] "Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"[e] |

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),[f] at some points known as the Russian Communist Party, All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet Communist Party (SCP), was the founding and ruling political party of the Soviet Union. The CPSU was the sole governing party of the Soviet Union until 1990 when the Congress of People's Deputies modified Article 6 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, which had previously granted the CPSU a monopoly over the political system. The party's main ideology was Marxism–Leninism.

The party started in 1898 as the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. In 1903, that party split into a Menshevik ("minority") and Bolshevik ("majority") faction; the latter, led by Vladimir Lenin, is the direct ancestor of the CPSU and is the party that seized power in the October Revolution of 1917. Its activities were suspended on Soviet territory 74 years later, on 29 August 1991, soon after a failed coup d'état by conservative CPSU leaders against the reforming Soviet president and party general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev.

The CPSU was a communist party based on democratic centralism. This principle, conceived by Lenin, entails democratic and open discussion of policy issues within the party, followed by the requirement of total unity in upholding the agreed policies. The highest body within the CPSU was the Party Congress, which convened every five years. When the Congress was not in session, the Central Committee was the highest body. Because the Central Committee met twice a year, most day-to-day duties and responsibilities were vested in the Politburo, (previously the Presidium), the Secretariat and the Orgburo (until 1952). The party leader was the head of government and held the office of either General Secretary, Premier or head of state, or two of the three offices concurrently, but never all three at the same time. The party leader was the de facto chairman of the CPSU Politburo and chief executive of the Soviet Union. The tension between the party and the state (Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union) for the shifting focus of power was never formally resolved.

After the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922, Lenin had introduced a mixed economy, commonly referred to as the New Economic Policy, which allowed for capitalist practices to resume under the Communist Party dictation in order to develop the necessary conditions for socialism to become a practical pursuit in the economically undeveloped country. In 1929, as Joseph Stalin became the leader of the party, Marxism–Leninism, a fusion of the original ideas of German philosopher and economic theorist Karl Marx, and Lenin, became formalized as the party's guiding ideology and would remain so throughout the rest of its existence. The party pursued state socialism, under which all industries were nationalized, and a command economy was implemented. After recovering from the Second World War, reforms were implemented which decentralized economic planning and liberalized Soviet society in general under Nikita Khrushchev. By 1980, various factors, including the continuing Cold War, and ongoing nuclear arms race with the United States and other Western European powers and unaddressed inefficiencies in the economy, led to stagnant economic growth under Alexei Kosygin, and further with Leonid Brezhnev and growing disillusionment. After the younger, vigorous Mikhail Gorbachev assumed leadership in 1985 (following two short-term elderly leaders, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, who quickly died in succession), rapid steps were taken to transform the tottering Soviet economic system in the direction of a market economy once again. Gorbachev and his allies envisioned the introduction of an economy similar to Lenin's earlier New Economic Policy through a program of "perestroika", or restructuring, but their reforms, along with the institution of free multi-candidate elections led to a decline in the party's power, and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the banning of the party by later last RSFSR President Boris Yeltsin and subsequent first President of an evolving democratic and free-market economy of the successor Russian Federation.

A number of causes contributed to CPSU's loss of control and the dissolution of the Soviet Union during the early 1990s. Some historians have written that Gorbachev's policy of "glasnost" (political openness) was the root cause, noting that it weakened the party's control over society. Gorbachev maintained that perestroika without glasnost was doomed to failure anyway. Others have blamed the economic stagnation and subsequent loss of faith by the general populace in communist ideology. In the final years of the CPSU's existence, the Communist Parties of the federal subjects of Russia were united into the Communist Party of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). After the CPSU's demise, the Communist Parties of the Union Republics became independent and underwent various separate paths of reform. In Russia, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation emerged and has been regarded as the inheritor of the CPSU's old Bolshevik legacy into the present day.[20]

History

Name

- 16 August 1917 – 8 March 1918: Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) (Russian: Российская социал-демократическая рабочая партия (большевиков); РСДРП(б), romanized: Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (bol'shevikov); RSDRP(b))

- 8 March 1918 – 31 December 1925: Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (Russian: Российская коммунистическая партия (большевиков); РКП(б), romanized: Rossiyskaya kommunisticheskaya partiya (bol'shevikov); RKP(b))

- 31 December 1925 – 14 October 1952: All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (Russian: Всесоюзная коммунистическая партия (большевиков); ВКП(б), romanized: Vsesoyuznaya kommunisticheskaya partiya (bol'shevikov); VKP(b))

- 14 October 1952 – 6 November 1991: Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Russian: Коммунистическая партия Советского Союза; КПСС, romanized: Kommunisticheskaya partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza; KPSS)

Early years (1898–1924)

The origin of the CPSU was in the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). This faction arose out of the split between followers of Julius Martov and Vladimir Lenin in August 1903 at the Party's second conference. Martov's followers were called the Mensheviks (which means minority in Russian); and Lenin's, the Bolsheviks (majority). (The two factions were in fact of fairly equal numerical size.) The split became more formalized in 1914, when the factions became named the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks), and Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Mensheviks). Prior to the February Revolution, the first phase of the Russian Revolutions of 1917, the party worked underground as organized anti-Tsarist groups. By the time of the revolution, many of the party's central leaders, including Lenin, were in exile.

After Emperor Nicholas II (1868–1918, reigned 1894–1917) abdicated in March 1917, a republic was established and administered by a provisional government, which was largely dominated by the interests of the military, former nobility, major capitalists business owners and democratic socialists. Alongside it, grassroots general assemblies spontaneously formed, called soviets, and a dual-power structure between the soviets and the provisional government was in place until such a time that their differences would be reconciled in a post-provisional government. Lenin was at this time in exile in Switzerland where he, with other dissidents in exile, managed to arrange with the Imperial German government safe passage through Germany in a sealed train back to Russia through the continent amidst the ongoing World War. In April, Lenin arrived in Petrograd (renamed former St. Petersburg) and condemned the provisional government, calling for the advancement of the revolution towards the transformation of the ongoing war into a war of the working class against capitalism. The rebellion proved not yet to be over, as tensions between the social forces aligned with the soviets (councils) and those with the provisional government now led by Alexander Kerensky (1881–1970, in power 1917), came into explosive tensions during that summer.

The Bolsheviks had rapidly increased their political presence from May onward through the popularity of their program, notably calling for an immediate end to the war, land reform for the peasants, and restoring food allocation to the urban population. This program was translated to the masses through simple slogans that patiently explained their solution to each crisis the revolution created. Up to July, these policies were disseminated through 41 publications, Pravda being the main paper, with a readership of 320,000. This was roughly halved after the repression of the Bolsheviks following the July Days demonstrations so that even by the end of August, the principal paper of the Bolsheviks had a print run of only 50,000 copies. Despite this, their ideas gained them increasing popularity in elections to the soviets.[21]

The factions within the soviets became increasingly polarized in the later summer after armed demonstrations by soldiers at the call of the Bolsheviks and an attempted military coup by commanding Gen. Lavr Kornilov to eliminate the socialists from the provisional government. As the general consensus within the soviets moved leftward, less militant forces began to abandon them, leaving the Bolsheviks in a stronger position. By October, the Bolsheviks were demanding the full transfer of power to the soviets and for total rejection of the Kerensky led provisional government's legitimacy. The provisional government, insistent on maintaining the universally despised war effort on the Eastern Front because of treaty ties with its Allies and fears of Imperial German victory, had become socially isolated and had no enthusiastic support on the streets. On 7 November (25 October, old style), the Bolsheviks led an armed insurrection, which overthrew the Kerensky provisional government and left the soviets as the sole governing force in Russia.

In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the soviets united federally and the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, the world's first constitutionally socialist state, was established.[22] The Bolsheviks were the majority within the soviets and began to fulfill their campaign promises by signing a damaging peace to end the war with the Germans in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and transferring estates and imperial lands to workers' and peasants' soviets.[22] In this context, in 1918, RSDLP(b) became All-Russian Communist Party (bolsheviks). Outside of Russia, social-democrats who supported the Soviet government began to identify as communists, while those who opposed it retained the social-democratic label.

In 1921, as the Civil War was drawing to a close, Lenin proposed the New Economic Policy (NEP), a system of state capitalism that started the process of industrialization and post-war recovery.[23] The NEP ended a brief period of intense rationing called "war communism" and began a period of a market economy under Communist dictation. The Bolsheviks believed at this time that Russia, being among the most economically undeveloped and socially backward countries in Europe, had not yet reached the necessary conditions of development for socialism to become a practical pursuit and that this would have to wait for such conditions to arrive under capitalist development as had been achieved in more advanced countries such as England and Germany. On 30 December 1922, the Russian SFSR joined former territories of the Russian Empire to form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), of which Lenin was elected leader.[24] On 9 March 1923, Lenin suffered a stroke, which incapacitated him and effectively ended his role in government. He died on 21 January 1924,[24] only thirteen months after the founding of the Soviet Union, of which he would become regarded as the founding father.

Stalin era (1924–53)

After Lenin's death, a power struggle ensued between Joseph Stalin, the party's General Secretary, and Leon Trotsky, the Minister of Defence, each with highly contrasting visions for the future direction of the country. Trotsky sought to implement a policy of permanent revolution, which was predicated on the notion that the Soviet Union would not be able to survive in a socialist character when surrounded by hostile governments and therefore concluded that it was necessary to actively support similar revolutions in the more advanced capitalist countries. Stalin, however, argued that such a foreign policy would not be feasible with the capabilities then possessed by the Soviet Union and that it would invite the country's destruction by engaging in armed conflict. Rather, Stalin argued that the Soviet Union should, in the meantime, pursue peaceful coexistence and invite foreign investment in order to develop the country's economy and build socialism in one country.

Ultimately, Stalin gained the greatest support within the party, and Trotsky, who was increasingly viewed as a collaborator with outside forces in an effort to depose Stalin, was isolated and subsequently expelled from the party and exiled from the country in 1928. Stalin's policies henceforth would later become collectively known as Stalinism. In 1925, the name of the party was changed to the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), reflecting that the republics outside of Russia proper were no longer part of an all-encompassing Russian state. The acronym was usually transliterated as VKP(b), or sometimes VCP(b). Stalin sought to formalize the party's ideological outlook into a philosophical hybrid of the original ideas of Lenin with orthodox Marxism into what would be called Marxism–Leninism. Stalin's position as General Secretary became the top executive position within the party, giving Stalin significant authority over party and state policy.

By the end of the 1920s, diplomatic relations with Western countries were deteriorating to the point that there was a growing fear of another allied attack on the Soviet Union. Within the country, the conditions of the NEP had enabled growing inequalities between increasingly wealthy strata and the remaining poor. The combination of these tensions led the party leadership to conclude that it was necessary for the government's survival to pursue a new policy that would centralize economic activity and accelerate industrialization. To do this, the first five-year plan was implemented in 1928. The plan doubled the industrial workforce, proletarianizing many of the peasants by removing them from their land and assembling them into urban centers. Peasants who remained in agricultural work were also made to have a similarly proletarian relationship to their labor through the policies of collectivization, which turned feudal-style farms into collective farms which would be in a cooperative nature under the direction of the state. These two shifts changed the base of Soviet society towards a more working-class alignment. The plan was fulfilled ahead of schedule in 1932.

The success of industrialization in the Soviet Union led Western countries, such as the United States, to open diplomatic relations with the Soviet government.[25] In 1933, after years of unsuccessful workers' revolutions (including a short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic) and spiraling economic calamity, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, violently suppressing the revolutionary organizers and posing a direct threat to the Soviet Union that ideologically supported them. The threat of fascist sabotage and imminent attack greatly exacerbated the already existing tensions within the Soviet Union and the Communist Party. A wave of paranoia overtook Stalin and the party leadership and spread through Soviet society. Seeing potential enemies everywhere, leaders of the government security apparatuses began severe crackdowns known as the Great Purge. In total, hundreds of thousands of people, many of whom were posthumously recognized as innocent, were arrested and either sent to prison camps or executed. Also during this time, a campaign against religion was waged in which the Russian Orthodox Church, which had long been a political arm of Tsarism before the revolution, was ruthlessly repressed, organized religion was generally removed from public life and made into a completely private matter, with many churches, mosques and other shrines being repurposed or demolished.

The Soviet Union was the first to warn of the impending danger of invasion from Nazi Germany to the international community. The Western powers, however, remained committed to maintaining peace and avoiding another war breaking out, many considering the Soviet Union's warnings to be an unwanted provocation. After many unsuccessful attempts to create an anti-fascist alliance among the Western countries, including trying to rally international support for the Spanish Republic in its struggle against a nationalist military coup which received supported from Germany and Italy, in 1939 the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Germany, later jointly invading and partitioning Poland to fulfil a secret protocol of the pact, as well as occupying the Baltic States, this pact would be broken in June 1941 when the German military invaded the Soviet Union in the largest land invasion in history, beginning the Great Patriotic War.

The Communist International was dissolved in 1943 after it was concluded that such an organization had failed to prevent the rise of fascism and the global war necessary to defeat it. After the 1945 Allied victory of World War II, the Party held to a doctrine of establishing socialist governments in the post-war occupied territories that would be administered by Communists loyal to Stalin's administration. The party also sought to expand its sphere of influence beyond the occupied territories, using proxy wars and espionage and providing training and funding to promote Communist elements abroad, leading to the establishment of the Cominform in 1947.

In 1949, the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War, causing an extreme shift in the global balance of forces and greatly escalating tensions between the Communists and the Western powers, fueling the Cold War. In Europe, Yugoslavia, under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, acquired the territory of Trieste, causing conflict both with the Western powers and with the Stalin administration who opposed such a provocative move. Furthermore, the Yugoslav Communists actively supported the Greek Communists during their civil war, further frustrating the Soviet government. These tensions led to a Tito–Stalin split, which marked the beginning of international sectarian division within the world communist movement.

Post-Stalin years (1953–85)

After Stalin's death, Nikita Khrushchev rose to the top post by overcoming political adversaries, including Lavrentiy Beria and Georgy Malenkov, in a power struggle.[26] In 1955, Khrushchev achieved the demotion of Malenkov and secured his own position as Soviet leader.[27] Early in his rule and with the support of several members of the Presidium, Khrushchev initiated the Thaw, which effectively ended the Stalinist mass terror of the prior decades and reduced socio-economic oppression considerably.[28] At the 20th Congress held in 1956, Khrushchev denounced Stalin's crimes, being careful to omit any reference to complicity by any sitting Presidium members.[29] His economic policies, while bringing about improvements, were not enough to fix the fundamental problems of the Soviet economy. The standard of living for ordinary citizens did increase; 108 million people moved into new housing between 1956 and 1965.[30]

Khrushchev's foreign policies led to the Sino-Soviet split, in part a consequence of his public denunciation of Stalin.[31] Khrushchev improved relations with Josip Broz Tito's League of Communists of Yugoslavia but failed to establish the close, party-to-party relations that he wanted.[30] While the Thaw reduced political oppression at home, it led to unintended consequences abroad, such as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and unrest in Poland, where the local citizenry now felt confident enough to rebel against Soviet control.[32] Khrushchev also failed to improve Soviet relations with the West, partially because of a hawkish military stance.[32] In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Khrushchev's position within the party was substantially weakened.[33] Shortly before his eventual ousting, he tried to introduce economic reforms championed by Evsei Liberman, a Soviet economist, which tried to implement market mechanisms into the planned economy.[34]

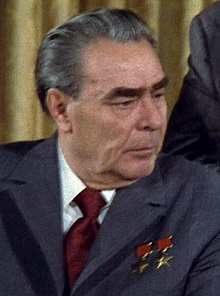

Khrushchev was ousted on 14 October 1964 in a Central Committee plenum that officially cited his inability to listen to others, his failure in consulting with the members of the Presidium, his establishment of a cult of personality, his economic mismanagement, and his anti-party reforms as the reasons he was no longer fit to remain as head of the party.[35] He was succeeded in office by Leonid Brezhnev as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[36]

The Brezhnev era began with a rejection of Khrushchevism in virtually every arena except one: continued opposition to Stalinist methods of terror and political violence.[38] Khrushchev's policies were criticized as voluntarism, and the Brezhnev period saw the rise of neo-Stalinism.[39] While Stalin was never rehabilitated during this period, the most conservative journals in the country were allowed to highlight positive features of his rule.[39]

At the 23rd Congress held in 1966, the names of the office of First Secretary and the body of the Presidium reverted to their original names: General Secretary and Politburo, respectively.[40] At the start of his premiership, Kosygin experimented with economic reforms similar to those championed by Malenkov, including prioritizing light industry over heavy industry to increase the production of consumer goods.[41] Similar reforms were introduced in Hungary under the name New Economic Mechanism; however, with the rise to power of Alexander Dubček in Czechoslovakia, who called for the establishment of "socialism with a human face", all non-conformist reform attempts in the Soviet Union were stopped.[42]

During his rule, Brezhnev supported détente, a passive weakening of animosity with the West with the goal of improving political and economic relations.[43] However, by the 25th Congress held in 1976, political, economic and social problems within the Soviet Union began to mount, and the Brezhnev administration found itself in an increasingly difficult position.[44] The previous year, Brezhnev's health began to deteriorate. He became addicted to painkillers and needed to take increasingly more potent medications to attend official meetings.[45] Because of the "trust in cadres" policy implemented by his administration, the CPSU leadership evolved into a gerontocracy.[46] At the end of Brezhnev's rule, problems continued to amount; in 1979 he consented to the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan to save the embattled communist regime there and supported the oppression of the Solidarity movement in Poland. As problems grew at home and abroad, Brezhnev was increasingly ineffective in responding to the growing criticism of the Soviet Union by Western leaders, most prominently by US Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[47] The CPSU, which had wishfully interpreted the financial crisis of the 1970s as the beginning of the end of capitalism, found its country falling far behind the West in its economic development.[48] Brezhnev died on 10 November 1982, and was succeeded by Yuri Andropov on 12 November.[49]

Andropov, a staunch anti-Stalinist, chaired the KGB during most of Brezhnev's reign.[50] He had appointed several reformers to leadership positions in the KGB, many of whom later became leading officials under Gorbachev.[50] Andropov supported increased openness in the press, particularly regarding the challenges facing the Soviet Union.[51] Andropov was in office briefly, but he appointed a number of reformers, including Yegor Ligachev, Nikolay Ryzhkov and Mikhail Gorbachev, to important positions. He also supported a crackdown on absenteeism and corruption.[51] Andropov had intended to let Gorbachev succeed him in office, but Konstantin Chernenko and his supporters suppressed the paragraph in the letter which called for Gorbachev's elevation.[51] Andropov died on 9 February 1984 and was succeeded by Chernenko.[52] The elderly Cherneko was in poor health throughout his short leadership and was unable to consolidate power; effective control of the party organization remained with Gorbachev.[52] Chernenko died on 10 March 1985 and was succeeded in office by Gorbachev the next day.[52]

Gorbachev and the party's demise (1985–91)

The Politburo did not want another elderly and frail leader after its previous three leaders, and elected Gorbachev as CPSU General Secretary on 11 March 1985, one day after Chernenko's death.[53] When Gorbachev acceded to power, the Soviet Union was stagnating but was stable and might have continued largely unchanged into the 21st century if not for Gorbachev's reforms.[54]

Gorbachev conducted a significant personnel reshuffling of the CPSU leadership, forcing old party conservatives out of office.[55] In 1985 and early 1986 the new leadership of the party called for uskoreniye (Russian: ускоре́ние, lit. 'acceleration').[55] Gorbachev reinvigorated the party ideology, adding new concepts and updating older ones.[55] Positive consequences of this included the allowance of "pluralism of thought" and a call for the establishment of "socialist pluralism" (literally, socialist democracy).[56] Gorbachev introduced a policy of glasnost (Russian: гла́сность, meaning openness or transparency) in 1986, which led to a wave of unintended democratization.[57] According to the British researcher of Russian affairs, Archie Brown, the democratization of the Soviet Union brought mixed blessings to Gorbachev; it helped him to weaken his conservative opponents within the party but brought out accumulated grievances which had been suppressed during the previous decades.[57]

In reaction to these changes, a conservative movement gained momentum in 1987 in response to Boris Yeltsin's dismissal as First Secretary of the CPSU Moscow City Committee.[58] On 13 March 1988, Nina Andreyeva, a university lecturer, wrote an article titled "I Cannot Forsake My Principles".[59] The publication was planned to occur when both Gorbachev and his protege Alexander Yakovlev were visiting foreign countries.[59] In their place, Yegor Ligachev led the party organization and told journalists that the article was "a benchmark for what we need in our ideology today".[59] Upon Gorbachev's return, the article was discussed at length during a Politburo meeting; it was revealed that nearly half of its members were sympathetic to the letter and opposed further reforms which could weaken the party.[59] The meeting lasted for two days, but on 5 April a Politburo resolution responded with a point-by-point rebuttal to Andreyeva's article.[59]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Communist_Party_of_Soviet_Union

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk