A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air flying under its own power.[1] Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air to achieve the lift needed to stay airborne.

In early dirigibles, the lifting gas used was hydrogen, due to its high lifting capacity and ready availability, but the inherent flammability led to several fatal accidents that rendered hydrogen airships obsolete. The alternative lifting gas, helium gas is not flammable, but is rare and relatively expensive. Significant amounts were first discovered in the United States and for a while helium was only available for airship usage in North America.[2] Most airships built since the 1960s have used helium, though some have used hot air.[note 1]

The envelope of an airship may form the gasbag, or it may contain a number of gas-filled cells. An airship also has engines, crew, and optionally also payload accommodation, typically housed in one or more gondolas suspended below the envelope.

The main types of airship are non-rigid, semi-rigid and rigid airships.[3] Non-rigid airships, often called "blimps", rely solely on internal gas pressure to maintain the envelope shape. Semi-rigid airships maintain their shape by internal pressure, but have some form of supporting structure, such as a fixed keel, attached to it. Rigid airships have an outer structural framework that maintains the shape and carries all structural loads, while the lifting gas is contained in one or more internal gasbags or cells.[4] Rigid airships were first flown by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin and the vast majority of rigid airships built were manufactured by the firm he founded, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin. As a result, rigid airships are often called zeppelins.[5]

Airships were the first aircraft capable of controlled powered flight, and were most commonly used before the 1940s; their use decreased as their capabilities were surpassed by those of aeroplanes. Their decline was accelerated by a series of high-profile accidents, including the 1930 crash and burning of the British R101 in France, the 1933 and 1935 storm-related crashes of the twin airborne aircraft carrier U.S. Navy helium-filled rigids, the USS Akron and USS Macon respectively, and the 1937 burning of the German hydrogen-filled Hindenburg. From the 1960s, helium airships have been used where the ability to hover for a long time outweighs the need for speed and manoeuvrability, such as advertising, tourism, camera platforms, geological surveys and aerial observation.

Terminology

Airship

During the pioneer years of aeronautics, terms such as "airship", "air-ship", "air ship" and "ship of the air" meant any kind of navigable or dirigible flying machine.[6][7][8][9][10][11] In 1919 Frederick Handley Page was reported as referring to "ships of the air", with smaller passenger types as "air yachts".[12] In the 1930s, large intercontinental flying boats were also sometimes referred to as "ships of the air" or "flying-ships".[13][14] Nowadays the term "airship" is used only for powered, dirigible balloons, with sub-types being classified as rigid, semi-rigid or non-rigid.[3] Semi-rigid architecture is the more recent, following advances in deformable structures and the exigency of reducing weight and volume of the airships. They have a minimal structure that keeps the shape jointly with overpressure of the gas envelope.[15][16]

Aerostat

An aerostat is an aircraft that remains aloft using buoyancy or static lift, as opposed to the aerodyne, which obtains lift by moving through the air. Airships are a type of aerostat.[3] The term aerostat has also been used to indicate a tethered or moored balloon as opposed to a free-floating balloon.[17] Aerostats today are capable of lifting a payload of 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) to an altitude of more than 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) above sea level.[18] They can also stay in the air for extended periods of time, particularly when powered by an on-board generator or if the tether contains electrical conductors.[18] Due to this capability, aerostats can be used as platforms for telecommunication services. For instance, Platform Wireless International Corporation announced in 2001 that it would use a tethered 1,250 pounds (570 kg) airborne payload to deliver cellular phone service to a 140 miles (230 km) region in Brazil.[19][20] The European Union's ABSOLUTE project was also reportedly exploring the use of tethered aerostat stations to provide telecommunications during disaster response.[21]

Blimp

A blimp is a non-rigid aerostat.[22] In British usage it refers to any non-rigid aerostat, including barrage balloons and other kite balloons, having a streamlined shape and stabilising tail fins.[23] Some blimps may be powered dirigibles, as in early versions of the Goodyear Blimp. Later Goodyear dirigibles, though technically semi-rigid airships, have still been called "blimps" by the company.[24]

Zeppelin

The term zeppelin originally referred to airships manufactured by the German Zeppelin Company, which built and operated the first rigid airships in the early years of the twentieth century. The initials LZ, for Luftschiff Zeppelin (German for "Zeppelin airship"), usually prefixed their craft's serial identifiers.

Streamlined rigid (or semi-rigid)[25] airships are often referred to as "Zeppelins", because of the fame that this company acquired due to the number of airships it produced,[26][27] although its early rival was the Parseval semi-rigid design.

Hybrid airship

Hybrid airships fly with a positive aerostatic contribution, usually equal to the empty weight of the system, and the variable payload is sustained by propulsion or aerodynamic contribution.[28][29]

Classification

Airships are classified according to their method of construction into rigid, semi-rigid and non-rigid types.[3]

Rigid

A rigid airship has a rigid framework covered by an outer skin or envelope. The interior contains one or more gasbags, cells or balloons to provide lift. Rigid airships are typically unpressurised and can be made to virtually any size. Most, but not all, of the German Zeppelin airships have been of this type.

Semi-rigid

A semi-rigid airship has some kind of supporting structure but the main envelope is held in shape by the internal pressure of the lifting gas. Typically the airship has an extended, usually articulated keel running along the bottom of the envelope to stop it kinking in the middle by distributing suspension loads into the envelope, while also allowing lower envelope pressures.

Non-rigid

Non-rigid airships are often called "blimps". Most, but not all, of the American Goodyear airships have been blimps.

A non-rigid airship relies entirely on internal gas pressure to retain its shape during flight. Unlike the rigid design, the non-rigid airship's gas envelope has no compartments. However, it still typically has smaller internal bags containing air (ballonets). As altitude is increased, the lifting gas expands and air from the ballonets is expelled through valves to maintain the hull's shape. To return to sea level, the process is reversed: air is forced back into the ballonets by scooping air from the engine exhaust and using auxiliary blowers.

Construction

Envelope

The envelope itself is the structure, including textiles that contain the buoyant gas. Internally two ballonets are generally placed in the front part and in the rear part of the hull and contains air.[30]

The problem of the exact determination of the pressure on an airship envelope is still problematic and has fascinated major scientists such as Theodor Von Karman.[31]

A few airships have been metal-clad, with rigid and nonrigid examples made. Each kind used a thin gastight metal envelope, rather than the usual rubber-coated fabric envelope. Only four metal-clad ships are known to have been built, and only two actually flew: Schwarz's first aluminum rigid airship of 1893 collapsed,[32] while his second flew;[33] the nonrigid ZMC-2 built for the U.S. Navy flew from 1929 to 1941 when it was scrapped as too small for operational use on anti-submarine patrols;[34] while the 1929 nonrigid Slate Aircraft Corporation City of Glendale collapsed on its first flight attempt.[35][36]

Ballonet

A ballonet is an air bag inside the outer envelope of an airship which, when inflated, reduces the volume available for the lifting gas, making it more dense. Because air is also denser than the lifting gas, inflating the ballonet reduces the overall lift, while deflating it increases lift. In this way, the ballonet can be used to adjust the lift as required by controlling the buoyancy. By inflating or deflating ballonets strategically, the pilot can control the airship's altitude and attitude.

Ballonets may typically be used in non-rigid or semi-rigid airships, commonly with multiple ballonets located both fore and aft to maintain balance and to control the pitch of the airship.

Lifting gas

Lifting gas is generally hydrogen, helium or hot air.

Hydrogen gives the highest lift 1.1 kg/m3 (0.069 lb/cu ft) and is inexpensive and easily obtained, but is highly flammable and can detonate if mixed with air. Helium is completely non flammable, but gives lower performance-1.02 kg/m3 (0.064 lb/cu ft) and is a rare element and much more expensive.[37]

Thermal airships use a heated lifting gas, usually air, in a fashion similar to hot air balloons. The first to do so was flown in 1973 by the British company Cameron Balloons.[38]

Gondola

Propulsion and control

This section needs to be updated. (December 2019) |

Small airships carry their engine(s) in their gondola. Where there were multiple engines on larger airships, these were placed in separate nacelles, termed power cars or engine cars.[39] To allow asymmetric thrust to be applied for maneuvering, these power cars were mounted towards the sides of the envelope, away from the centre line gondola. This also raised them above the ground, reducing the risk of a propeller strike when landing. Widely spaced power cars were also termed wing cars, from the use of "wing" to mean being on the side of something, as in a theater, rather than the aerodynamic device.[39] These engine cars carried a crew during flight who maintained the engines as needed, but who also worked the engine controls, throttle etc., mounted directly on the engine. Instructions were relayed to them from the pilot's station by a telegraph system, as on a ship.[39]

If fuel is burnt for propulsion, then progressive reduction in the airship's overall weight occurs. In hydrogen airships, this is usually dealt with by simply venting cheap hydrogen lifting gas. In helium airships water is often condensed from the exhaust and stored as ballast.[40]

Fins and rudders

To control the airship's direction and stability, it is equipped with fins and rudders. Fins are typically located on the tail section and provide stability and resistance to rolling. Rudders are movable surfaces on the tail that allow the pilot to steer the airship left or right.

Empennage

The empennage refers to the tail section of the airship, which includes the fins, rudders, and other aerodynamic surfaces. It plays a crucial role in maintaining stability and controlling the airship's attitude.

Fuel and power systems

Airships require a source of power to operate their propulsion systems. This includes engines, generators, or batteries, depending on the type of airship and its design. Fuel tanks or batteries are typically located within the envelope or gondola.

To navigate safely and communicate with ground control or other aircraft, airships are equipped with a range of instruments, including GPS systems, radios, radar, and navigation lights.

Landing gear

Some airships have landing gear that allows them to land on runways or other surfaces. This landing gear may include wheels, skids, or landing pads.

Performance

Efficiency

The main advantage of airships with respect to any other vehicle is that they require less energy to remain in flight, compared to other air vehicles.[41][42] The proposed Varialift airship, powered by a mixture of solar-powered engines and conventional jet engines, would use only an estimated 8 percent of the fuel required by jet aircraft.[43][44] Furthermore, utilizing the jet stream could allow for a faster and more energy-efficient cargo transport alternative to maritime shipping.[45] This is one of the reasons why China has embraced their use recently.[46]

History

Early pioneersedit

17th–18th centuryedit

In 1670, the Jesuit Father Francesco Lana de Terzi, sometimes referred to as the "Father of Aeronautics",[47] published a description of an "Aerial Ship" supported by four copper spheres from which the air was evacuated. Although the basic principle is sound, such a craft was unrealizable then and remains so to the present day, since external air pressure would cause the spheres to collapse unless their thickness was such as to make them too heavy to be buoyant.[48] A hypothetical craft constructed using this principle is known as a vacuum airship.

In 1709, the Brazilian-Portuguese Jesuit priest Bartolomeu de Gusmão made a hot air balloon, the Passarola, ascend to the skies, before an astonished Portuguese court. It would have been on August 8, 1709, when Father Bartolomeu de Gusmão held, in the courtyard of the Casa da Índia, in the city of Lisbon, the first Passarola demonstration.[49][50] The balloon caught fire without leaving the ground, but, in a second demonstration, it rose to 95 meters in height. It was a small balloon of thick brown paper, filled with hot air, produced by the "fire of material contained in a clay bowl embedded in the base of a waxed wooden tray". The event was witnessed by King John V of Portugal and the future Pope Innocent XIII.[51]

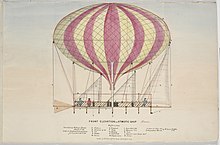

A more practical dirigible airship was described by Lieutenant Jean Baptiste Marie Meusnier in a paper entitled "Mémoire sur l'équilibre des machines aérostatiques" (Memorandum on the equilibrium of aerostatic machines) presented to the French Academy on 3 December 1783. The 16 water-color drawings published the following year depict a 260-foot-long (79 m) streamlined envelope with internal ballonets that could be used for regulating lift: this was attached to a long carriage that could be used as a boat if the vehicle was forced to land in water. The airship was designed to be driven by three propellers and steered with a sail-like aft rudder. In 1784, Jean-Pierre Blanchard fitted a hand-powered propeller to a balloon, the first recorded means of propulsion carried aloft. In 1785, he crossed the English Channel in a balloon equipped with flapping wings for propulsion and a birdlike tail for steering.[52]

19th centuryedit

The 19th century saw continued attempts to add methods of propulsion to balloons. Rufus Porter built and flew scale models of his "Aerial Locomotive", but never a successful full-size implementation.[53] The Australian William Bland sent designs for his "Atmotic airship" to the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851, where a model was displayed. This was an elongated balloon with a steam engine driving twin propellers suspended underneath. The lift of the balloon was estimated as 5 tons and the car with the fuel as weighing 3.5 tons, giving a payload of 1.5 tons.[54][55] Bland believed that the machine could be driven at 80 km/h (50 mph) and could fly from Sydney to London in less than a week.

In 1852, Henri Giffard became the first person to make an engine-powered flight when he flew 27 km (17 mi) in a steam-powered airship.[56] Airships would develop considerably over the next two decades. In 1863, Solomon Andrews flew his aereon design, an unpowered, controllable dirigible in Perth Amboy, New Jersey and offered the device to the U.S. Military during the Civil War.[57] He flew a later design in 1866 around New York City and as far as Oyster Bay, New York. This concept used changes in lift to provide propulsive force, and did not need a powerplant. In 1872, the French naval architect Dupuy de Lome launched a large navigable balloon, which was driven by a large propeller turned by eight men.[58] It was developed during the Franco-Prussian war and was intended as an improvement to the balloons used for communications between Paris and the countryside during the siege of Paris, but was completed only after the end of the war.

In 1872, Paul Haenlein flew an airship with an internal combustion engine running on the coal gas used to inflate the envelope, the first use of such an engine to power an aircraft.[59][60] Charles F. Ritchel made a public demonstration flight in 1878 of his hand-powered one-man rigid airship, and went on to build and sell five of his aircraft.[60]

In 1874, Micajah Clark Dyer filed U.S. Patent 154,654 "Apparatus for Navigating the Air".[61][62][63] It is believed successful trial flights were made between 1872 and 1874, but detailed dates are not available.[64] The apparatus used a combination of wings and paddle wheels for navigation and propulsion.

In operating the machinery the wings receive an upward and downward motion, in the manner of the wings of a bird, the outer ends yielding as they are raised, but opening out and then remaining rigid while being depressed. The wings, if desired, may be set at an angle so as to propel forward as well as to raise the machine in the air. The paddle-wheels are intended to be used for propelling the machine, in the same way that a vessel is propelled in water. An instrument answering to a rudder is attached for guiding the machine. A balloon is to be used for elevating the flying ship, after which it is to be guided and controlled at the pleasure of its occupants.[65]

More details can be found in the book about his life.[66]

In 1883, the first electric-powered flight was made by Gaston Tissandier, who fitted a 1.5 hp (1.1 kW) Siemens electric motor to an airship.

The first fully controllable free flight was made in 1884 by Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs in the French Army airship La France. La France made the first flight of an airship that landed where it took off; the 170 ft (52 m) long, 66,000 cu ft (1,900 m3) airship covered 8 km (5.0 mi) in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8.5 hp (6.3 kW) electric motor,[67] and a 435 kg (959 lb) battery. It made seven flights in 1884 and 1885.[60]

In 1888, the design of the Campbell Air Ship, designed by Professor Peter C. Campbell, was built by the Novelty Air Ship Company. It was lost at sea in 1889 while being flown by Professor Hogan during an exhibition flight.[68]

From 1888 to 1897, Friedrich Wölfert built three airships powered by Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft-built petrol engines, the last of which, Deutschland, caught fire in flight and killed both occupants in 1897.[69] The 1888 version used a 2 hp (1.5 kW) single cylinder Daimler engine and flew 10 km (6 mi) from Canstatt to Kornwestheim.[70][71]

In 1897, an airship with an aluminum envelope was built by the Hungarian-Croatian engineer David Schwarz. It made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin after Schwarz had died. His widow, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 marks by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin to release the industrialist Carl Berg from his exclusive contract to supply Schwartz with aluminium.[72]

From 1897 to 1899, Konstantin Danilewsky, medical doctor and inventor from Kharkiv (now Ukraine, then Russian Empire), built four muscle-powered airships, of gas volume 150–180 m3 (5,300–6,400 cu ft). About 200 ascents were made within a framework of experimental flight program, at two locations, with no significant incidents.[73][74]

Early 20th centuryedit

In July 1900, the Luftschiff Zeppelin LZ1 made its first flight. This led to the most successful airships of all time: the Zeppelins, named after Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin who began working on rigid airship designs in the 1890s, leading to the flawed LZ1 in 1900 and the more successful LZ2 in 1906. The Zeppelin airships had a framework composed of triangular lattice girders covered with fabric that contained separate gas cells. At first multiplane tail surfaces were used for control and stability: later designs had simpler cruciform tail surfaces. The engines and crew were accommodated in "gondolas" hung beneath the hull driving propellers attached to the sides of the frame by means of long drive shafts. Additionally, there was a passenger compartment (later a bomb bay) located halfway between the two engine compartments.

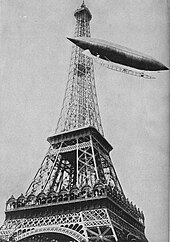

Alberto Santos-Dumont was a wealthy young Brazilian who lived in France and had a passion for flying. He designed 18 balloons and dirigibles before turning his attention to fixed-winged aircraft.[75] On 19 October 1901 he flew his airship Number 6, from the Parc Saint Cloud to and around the Eiffel Tower and back in under thirty minutes.[76] This feat earned him the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize of 100,000 francs. Many inventors were inspired by Santos-Dumont's small airships. Many airship pioneers, such as the American Thomas Scott Baldwin, financed their activities through passenger flights and public demonstration flights. Stanley Spencer built the first British airship with funds from advertising baby food on the sides of the envelope.[77] Others, such as Walter Wellman and Melvin Vaniman, set their sights on loftier goals, attempting two polar flights in 1907 and 1909, and two trans-Atlantic flights in 1910 and 1912.[78]

In 1902 the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo published details of an innovative airship design in Spain and France titled "Perfectionnements aux aerostats dirigibles" ("Improvements in dirigible aerostats").[79][80] With a non-rigid body and internal bracing wires, it overcame the flaws of these types of aircraft as regards both rigid structure (zeppelin type) and flexibility, providing the airships with more stability during flight, and the capability of using heavier engines and a greater passenger load. A system called "auto-rigid". In 1905, helped by Captain A. Kindelán, he built the airship "Torres Quevedo" at the Guadalajara military base.[81] In 1909 he patented an improved design that he offered to the French Astra company, who started mass-producing it in 1911 as the Astra-Torres airship.[82] This type of envelope was employed in the United Kingdom in the Coastal, C Star, and North Sea airships.[83] The distinctive three-lobed design was widely used during the Great War by the Entente powers for diverse tasks, principally convoy protection and anti-submarine warfare. The success during the war even drew the attention of the Imperial Japanese Navy, who acquired a model in 1922.[84] Torres also drew up designs of a 'docking station' and made alterations to airship designs, to find a resolution to the slew of problems faced by airship engineers to dock dirigibles. In 1910, he proposed the idea of attaching an airships nose to a mooring mast and allowing the airship to weathervane with changes of wind direction. The use of a metal column erected on the ground, the top of which the bow or stem would be directly attached to (by a cable) would allow a dirigible to be moored at any time, in the open, regardless of wind speeds. Additionally, Torres' design called for the improvement and accessibility of temporary landing sites, where airships were to be moored for the purpose of disembarkation of passengers. The final patent was presented in February 1911 in Belgium, and later to France and the United Kingdom in 1912, under the title "Improvements in Mooring Arrengements for Airships".[85][86][87]

Other airship builders were also active before the war: from 1902 the French company Lebaudy Frères specialized in semirigid airships such as the Patrie and the République, designed by their engineer Henri Julliot, who later worked for the American company Goodrich; the German firm Schütte-Lanz built the wooden-framed SL series from 1911, introducing important technical innovations; another German firm Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft built the Parseval-Luftschiff (PL) series from 1909,[88] and Italian Enrico Forlanini's firm had built and flown the first two Forlanini airships.[89]

On May 12, 1902, the inventor and Brazilian aeronaut Augusto Severo de Albuquerque Maranhao and his French mechanic, Georges Saché, died when they were flying over Paris in the airship called Pax. A marble plaque at number 81 of the Avenue du Maine in Paris, commemorates the location of Augusto Severo accident.[90][91] The Catastrophe of the Balloon "Le Pax" is a 1902 short silent film recreation of the catastrophe, directed by Georges Méliès.

In Britain, the Army built their first dirigible, the Nulli Secundus, in 1907. The Navy ordered the construction of an experimental rigid in 1908. Officially known as His Majesty's Airship No. 1 and nicknamed the Mayfly, it broke its back in 1911 before making a single flight. Work on a successor did not start until 1913.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Dirigibles

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk