A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Ecological economics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

Ecological economics, bioeconomics, ecolonomy, eco-economics, or ecol-econ is both a transdisciplinary and an interdisciplinary field of academic research addressing the interdependence and coevolution of human economies and natural ecosystems, both intertemporally and spatially.[1] By treating the economy as a subsystem of Earth's larger ecosystem, and by emphasizing the preservation of natural capital, the field of ecological economics is differentiated from environmental economics, which is the mainstream economic analysis of the environment.[2] One survey of German economists found that ecological and environmental economics are different schools of economic thought, with ecological economists emphasizing strong sustainability and rejecting the proposition that physical (human-made) capital can substitute for natural capital (see the section on weak versus strong sustainability below).[3]

Ecological economics was founded in the 1980s as a modern discipline on the works of and interactions between various European and American academics (see the section on History and development below). The related field of green economics is in general a more politically applied form of the subject.[4][5]

According to ecological economist Malte Michael Faber, ecological economics is defined by its focus on nature, justice, and time. Issues of intergenerational equity, irreversibility of environmental change, uncertainty of long-term outcomes, and sustainable development guide ecological economic analysis and valuation.[6] Ecological economists have questioned fundamental mainstream economic approaches such as cost-benefit analysis, and the separability of economic values from scientific research, contending that economics is unavoidably normative, i.e. prescriptive, rather than positive or descriptive.[7] Positional analysis, which attempts to incorporate time and justice issues, is proposed as an alternative.[8][9] Ecological economics shares several of its perspectives with feminist economics, including the focus on sustainability, nature, justice and care values.[10] Karl Marx also commented on relationship between capital and ecology, what is now known as ecosocialism.[11]

History and development

The antecedents of ecological economics can be traced back to the Romantics of the 19th century as well as some Enlightenment political economists of that era. Concerns over population were expressed by Thomas Malthus, while John Stuart Mill predicted the desirability of the stationary state of an economy. Mill thereby anticipated later insights of modern ecological economists, but without having had their experience of the social and ecological costs of the Post–World War II economic expansion. In 1880, Marxian economist Sergei Podolinsky attempted to theorize a labor theory of value based on embodied energy; his work was read and critiqued by Marx and Engels.[12] Otto Neurath developed an ecological approach based on a natural economy whilst employed by the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919. He argued that a market system failed to take into account the needs of future generations, and that a socialist economy required calculation in kind, the tracking of all the different materials, rather than synthesising them into money as a general equivalent. In this he was criticised by neo-liberal economists such as Ludwig von Mises and Freidrich Hayek in what became known as the socialist calculation debate.[13]

The debate on energy in economic systems can also be traced back to Nobel prize-winning radiochemist Frederick Soddy (1877–1956). In his book Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt (1926), Soddy criticized the prevailing belief of the economy as a perpetual motion machine, capable of generating infinite wealth—a criticism expanded upon by later ecological economists such as Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Herman Daly.[14]

European predecessors of ecological economics include K. William Kapp (1950)[15] Karl Polanyi (1944),[16] and Romanian economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1971). Georgescu-Roegen, who would later mentor Herman Daly at Vanderbilt University, provided ecological economics with a modern conceptual framework based on the material and energy flows of economic production and consumption. His magnum opus, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (1971), is credited by Daly as a fundamental text of the field, alongside Soddy's Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt.[17] Some key concepts of what is now ecological economics are evident in the writings of Kenneth Boulding and E.F. Schumacher, whose book Small Is Beautiful – A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (1973) was published just a few years before the first edition of Herman Daly's comprehensive and persuasive Steady-State Economics (1977).[18][19]

The first organized meetings of ecological economists occurred in the 1980s. These began in 1982, at the instigation of Lois Banner,[20] with a meeting held in Sweden (including Robert Costanza, Herman Daly, Charles Hall, Bruce Hannon, H.T. Odum, and David Pimentel).[21] Most were ecosystem ecologists or mainstream environmental economists, with the exception of Daly. In 1987, Daly and Costanza edited an issue of Ecological Modeling to test the waters. A book entitled Ecological Economics, by Joan Martinez Alier, was published later that year.[21] Alier renewed interest in the approach developed by Otto Neurath during the interwar period.[22] The year 1989 saw the foundation of the International Society for Ecological Economics and publication of its journal, Ecological Economics, by Elsevier. Robert Costanza was the first president of the society and first editor of the journal, which is currently edited by Richard Howarth. Other figures include ecologists C.S. Holling and H.T. Odum, biologist Gretchen Daily, and physicist Robert Ayres. In the Marxian tradition, sociologist John Bellamy Foster and CUNY geography professor David Harvey explicitly center ecological concerns in political economy.

Articles by Inge Ropke (2004, 2005)[23] and Clive Spash (1999)[24] cover the development and modern history of ecological economics and explain its differentiation from resource and environmental economics, as well as some of the controversy between American and European schools of thought. An article by Robert Costanza, David Stern, Lining He, and Chunbo Ma[25] responded to a call by Mick Common to determine the foundational literature of ecological economics by using citation analysis to examine which books and articles have had the most influence on the development of the field. However, citations analysis has itself proven controversial and similar work has been criticized by Clive Spash for attempting to pre-determine what is regarded as influential in ecological economics through study design and data manipulation.[26] In addition, the journal Ecological Economics has itself been criticized for swamping the field with mainstream economics.[27][28]

Schools of thought

Various competing schools of thought exist in the field. Some are close to resource and environmental economics while others are far more heterodox in outlook. An example of the latter is the European Society for Ecological Economics. An example of the former is the Swedish Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics. Clive Spash has argued for the classification of the ecological economics movement, and more generally work by different economic schools on the environment, into three main categories. These are the mainstream new resource economists, the new environmental pragmatists,[29] and the more radical social ecological economists.[30] International survey work comparing the relevance of the categories for mainstream and heterodox economists shows some clear divisions between environmental and ecological economists.[31] A growing field of radical social-ecological theory is degrowth economics.[32]Degrowth addresses both biophysical limits and global inequality while rejecting neoliberal economics. Degrowth prioritizes grassroots initiatives in progressive socio-ecological goals, adhering to ecological limits by shrinking the human ecological footprint (See Differences from Mainstream Economics Below). It involves an equitable downscale in both production and consumption of resources in order to adhere to biophysical limits. Degrowth draws from Marxian economics, citing the growth of efficient systems as the alienation of nature and man.[33] Economic movements like degrowth reject the idea of growth itself. Some degrowth theorists call for an "exit of the economy".[34] Critics of the degrowth movement include new resource economists, who point to the gaining momentum of sustainable development. These economists highlight the positive aspects of a green economy, which include equitable access to renewable energy and a commitment to eradicate global inequality through sustainable development (See Green Economics).[34] Examples of heterodox ecological economic experiments include the Catalan Integral Cooperative and the Solidarity Economy Networks in Italy. Both of these grassroots movements use communitarian based economies and consciously reduce their ecological footprint by limiting material growth and adapting to regenerative agriculture.[35]

Non-traditional approaches to ecological economics

Cultural and heterodox applications of economic interaction around the world have begun to be included as ecological economic practices. E.F. Schumacher introduced examples of non-western economic ideas to mainstream thought in his book, Small is Beautiful, where he addresses neoliberal economics through the lens of natural harmony in Buddhist economics.[18] This emphasis on natural harmony is witnessed in diverse cultures across the globe. Buen Vivir is a traditional socio-economic movement in South America that rejects the western development model of economics. Meaning Good Life, Buen Vivir emphasizes harmony with nature, diverse pluralculturism, coexistence, and inseparability of nature and material. Value is not attributed to material accumulation, and it instead takes a more spiritual and communitarian approach to economic activity. Ecological Swaraj originated out of India, and is an evolving world view of human interactions within the ecosystem. This train of thought respects physical bio-limits and non-human species, pursuing equity and social justice through direct democracy and grassroots leadership. Social well-being is paired with spiritual, physical, and material well-being. These movements are unique to their region, but the values can be seen across the globe in indigenous traditions, such as the Ubuntu Philosophy in South Africa.[36]

Differences from mainstream economics

Ecological economics differs from mainstream economics in that it heavily reflects on the ecological footprint of human interactions in the economy. This footprint is measured by the impact of human activities on natural resources and the waste generated in the process. Ecological economists aim to minimize the ecological footprint, taking into account the scarcity of global and regional resources and their accessibility to an economy.[37] Some ecological economists prioritise adding natural capital to the typical capital asset analysis of land, labor, and financial capital. These ecological economists use tools from mathematical economics, as in mainstream economics, but may apply them more closely to the natural world. Whereas mainstream economists tend to be technological optimists, ecological economists are inclined to be technological sceptics. They reason that the natural world has a limited carrying capacity and that its resources may run out. Since destruction of important environmental resources could be practically irreversible and catastrophic, ecological economists are inclined to justify cautionary measures based on the precautionary principle.[38] As ecological economists try to minimize these potential disasters, calculating the fallout of environmental destruction becomes a humanitarian issue as well. Already, the Global South has seen trends of mass migration due to environmental changes. Climate refugees from the Global South are adversely affected by changes in the environment, and some scholars point to global wealth inequality within the current neoliberal economic system as a source of this issue.[39]

The most cogent example of how the different theories treat similar assets is tropical rainforest ecosystems, most obviously the Yasuni region of Ecuador. While this area has substantial deposits of bitumen it is also one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth and some estimates establish it has over 200 undiscovered medical substances in its genomes – most of which would be destroyed by logging the forest or mining the bitumen. Effectively, the instructional capital of the genomes is undervalued by analyses that view the rainforest primarily as a source of wood, oil/tar and perhaps food. Increasingly the carbon credit for leaving the extremely carbon-intensive ("dirty") bitumen in the ground is also valued – the government of Ecuador set a price of US$350M for an oil lease with the intent of selling it to someone committed to never exercising it at all and instead preserving the rainforest.

While this natural capital and ecosystems services approach has proven popular amongst many it has also been contested as failing to address the underlying problems with mainstream economics, growth, market capitalism and monetary valuation of the environment.[40][41][42] Critiques concern the need to create a more meaningful relationship with Nature and the non-human world than evident in the instrumentalism of shallow ecology and the environmental economists commodification of everything external to the market system.[43][44][45]

Nature and ecology

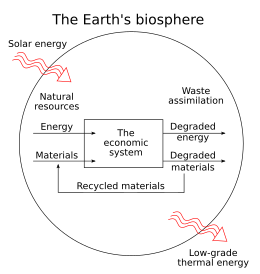

A simple circular flow of income diagram is replaced in ecological economics by a more complex flow diagram reflecting the input of solar energy, which sustains natural inputs and environmental services which are then used as units of production. Once consumed, natural inputs pass out of the economy as pollution and waste. The potential of an environment to provide services and materials is referred to as an "environment's source function", and this function is depleted as resources are consumed or pollution contaminates the resources. The "sink function" describes an environment's ability to absorb and render harmless waste and pollution: when waste output exceeds the limit of the sink function, long-term damage occurs.[46]: 8 Some persistent pollutants, such as some organic pollutants and nuclear waste are absorbed very slowly or not at all; ecological economists emphasize minimizing "cumulative pollutants".[46]: 28 Pollutants affect human health and the health of the ecosystem.

The economic value of natural capital and ecosystem services is accepted by mainstream environmental economics, but is emphasized as especially important in ecological economics. Ecological economists may begin by estimating how to maintain a stable environment before assessing the cost in dollar terms.[46]: 9 Ecological economist Robert Costanza led an attempted valuation of the global ecosystem in 1997. Initially published in Nature, the article concluded on $33 trillion with a range from $16 trillion to $54 trillion (in 1997, total global GDP was $27 trillion).[47] Half of the value went to nutrient cycling. The open oceans, continental shelves, and estuaries had the highest total value, and the highest per-hectare values went to estuaries, swamps/floodplains, and seagrass/algae beds. The work was criticized by articles in Ecological Economics Volume 25, Issue 1, but the critics acknowledged the positive potential for economic valuation of the global ecosystem.[46]: 129

The Earth's carrying capacity is a central issue in ecological economics. Early economists such as Thomas Malthus pointed out the finite carrying capacity of the earth, which was also central to the MIT study Limits to Growth. Diminishing returns suggest that productivity increases will slow if major technological progress is not made. Food production may become a problem, as erosion, an impending water crisis, and soil salinity (from irrigation) reduce the productivity of agriculture. Ecological economists argue that industrial agriculture, which exacerbates these problems, is not sustainable agriculture, and are generally inclined favorably to organic farming, which also reduces the output of carbon.[46]: 26

Global wild fisheries are believed to have peaked and begun a decline, with valuable habitat such as estuaries in critical condition.[46]: 28 The aquaculture or farming of piscivorous fish, like salmon, does not help solve the problem because they need to be fed products from other fish. Studies have shown that salmon farming has major negative impacts on wild salmon, as well as the forage fish that need to be caught to feed them.[48][49]

Since animals are higher on the trophic level, they are less efficient sources of food energy. Reduced consumption of meat would reduce the demand for food, but as nations develop, they tend to adopt high-meat diets similar to that of the United States. Genetically modified food (GMF) a conventional solution to the problem, presents numerous problems – Bt corn produces its own Bacillus thuringiensis toxin/protein, but the pest resistance is believed to be only a matter of time.[46]: 31

Global warming is now widely acknowledged as a major issue, with all national scientific academies expressing agreement on the importance of the issue. As the population growth intensifies and energy demand increases, the world faces an energy crisis. Some economists and scientists forecast a global ecological crisis if energy use is not contained – the Stern report is an example. The disagreement has sparked a vigorous debate on issue of discounting and intergenerational equity.

- GLOBAL GEOCHEMICAL CYCLES CRITICAL FOR LIFE

Ethics

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Mainstream economics has attempted to become a value-free 'hard science', but ecological economists argue that value-free economics is generally not realistic. Ecological economics is more willing to entertain alternative conceptions of utility, efficiency, and cost-benefits such as positional analysis or multi-criteria analysis. Ecological economics is typically viewed as economics for sustainable development,[50] and may have goals similar to green politics.

Green economics

In international, regional, and national policy circles, the concept of the green economy grew in popularity as a response to the financial predicament at first then became a vehicle for growth and development.[51]

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) defines a 'green economy' as one that focuses on the human aspects and natural influences and an economic order that can generate high-salary jobs. In 2011, its definition was further developed as the word 'green' is made to refer to an economy that is not only resourceful and well-organized but also impartial, guaranteeing an objective shift to an economy that is low-carbon, resource-efficient, and socially-inclusive.

The ideas and studies regarding the green economy denote a fundamental shift for more effective, resourceful, environment-friendly and resource‐saving technologies that could lessen emissions and alleviate the adverse consequences of climate change, at the same time confront issues about resource exhaustion and grave environmental dilapidation.[52]

As an indispensable requirement and vital precondition to realizing sustainable development, the Green Economy adherents robustly promote good governance. To boost local investments and foreign ventures, it is crucial to have a constant and foreseeable macroeconomic atmosphere. Likewise, such an environment will also need to be transparent and accountable. In the absence of a substantial and solid governance structure, the prospect of shifting towards a sustainable development route would be insignificant. In achieving a green economy, competent institutions and governance systems are vital in guaranteeing the efficient execution of strategies, guidelines, campaigns, and programmes.

Shifting to a Green Economy demands a fresh mindset and an innovative outlook of doing business. It likewise necessitates new capacities, skills set from labor and professionals who can competently function across sectors, and able to work as effective components within multi-disciplinary teams. To achieve this goal, vocational training packages must be developed with focus on greening the sectors. Simultaneously, the educational system needs to be assessed as well in order to fit in the environmental and social considerations of various disciplines.[53]

Topics

Among the topics addressed by ecological economics are methodology, allocation of resources, weak versus strong sustainability, energy economics, energy accounting and balance, environmental services, cost shifting, modeling, and monetary policy.

Methodology

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|