A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure.[1][2][3][4] There is no scientific consensus on a definition.[5][6] Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.[7]

Research on emotion has increased over the past two decades, with many fields contributing, including psychology, medicine, history, sociology of emotions, computer science and philosophy. The numerous attempts to explain the origin, function, and other aspects of emotions have fostered intense research on this topic. Theorizing about the evolutionary origin and possible purpose of emotion dates back to Charles Darwin. Current areas of research include the neuroscience of emotion, using tools like PET and fMRI scans to study the affective picture processes in the brain.[8]

From a mechanistic perspective, emotions can be defined as "a positive or negative experience that is associated with a particular pattern of physiological activity."[4] Emotions are complex, involving multiple different components, such as subjective experience, cognitive processes, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behavior.[9][10] At one time, academics attempted to identify the emotion with one of the components: William James with a subjective experience, behaviorists with instrumental behavior, psychophysiologists with physiological changes, and so on. More recently, emotion has been said to consist of all the components. The different components of emotion are categorized somewhat differently depending on the academic discipline. In psychology and philosophy, emotion typically includes a subjective, conscious experience characterized primarily by psychophysiological expressions, biological reactions, and mental states. A similar multi-componential description of emotion is found in sociology. For example, Peggy Thoits described emotions as involving physiological components, cultural or emotional labels (anger, surprise, etc.), expressive body actions, and the appraisal of situations and contexts.[11] Cognitive processes, like reasoning and decision-making, are often regarded as separate from emotional processes, making a division between "thinking" and "feeling". However, not all theories of emotion regard this separation as valid.[12]

Nowadays, most research into emotions in the clinical and well-being context focuses on emotion dynamics in daily life, predominantly the intensity of specific emotions and their variability, instability, inertia, and differentiation, as well as whether and how emotions augment or blunt each other over time and differences in these dynamics between people and along the lifespan.[13][14]

Etymology

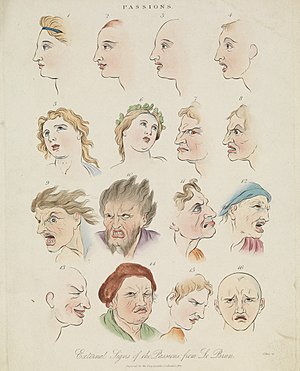

The word "emotion" dates back to 1579, when it was adapted from the French word émouvoir, which means "to stir up". The term emotion was introduced into academic discussion as a catch-all term to passions, sentiments and affections.[15] The word "emotion" was coined in the early 1800s by Thomas Brown and it is around the 1830s that the modern concept of emotion first emerged for the English language.[16] "No one felt emotions before about 1830. Instead they felt other things – 'passions', 'accidents of the soul', 'moral sentiments' – and explained them very differently from how we understand emotions today."[16]

Some cross-cultural studies indicate that the categorization of "emotion" and classification of basic emotions such as "anger" and "sadness" are not universal and that the boundaries and domains of these concepts are categorized differently by all cultures.[17] However, others argue that there are some universal bases of emotions (see Section 6.1).[18] In psychiatry and psychology, an inability to express or perceive emotion is sometimes referred to as alexithymia.[19]

History

Human nature and the accompanying bodily sensations have always been part of the interests of thinkers and philosophers. Far more extensively, this has also been of great interest to both Western and Eastern societies. Emotional states have been associated with the divine and with the enlightenment of the human mind and body.[20] The ever-changing actions of individuals and their mood variations have been of great importance to most of the Western philosophers (including Aristotle, Plato, Descartes, Aquinas, and Hobbes), leading them to propose extensive theories—often competing theories—that sought to explain emotion and the accompanying motivators of human action, as well as its consequences.

In the Age of Enlightenment, Scottish thinker David Hume[21] proposed a revolutionary argument that sought to explain the main motivators of human action and conduct. He proposed that actions are motivated by "fears, desires, and passions". As he wrote in his book A Treatise of Human Nature (1773): "Reason alone can never be a motive to any action of the will… it can never oppose passion in the direction of the will… The reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them".[22] With these lines, Hume attempted to explain that reason and further action would be subject to the desires and experience of the self. Later thinkers would propose that actions and emotions are deeply interrelated with social, political, historical, and cultural aspects of reality that would also come to be associated with sophisticated neurological and physiological research on the brain and other parts of the physical body.

Definitions

The Lexico definition of emotion is "A strong feeling deriving from one's circumstances, mood, or relationships with others."[23] Emotions are responses to significant internal and external events.[24]

Emotions can be occurrences (e.g., panic) or dispositions (e.g., hostility), and short-lived (e.g., anger) or long-lived (e.g., grief).[25] Psychotherapist Michael C. Graham describes all emotions as existing on a continuum of intensity.[26] Thus fear might range from mild concern to terror or shame might range from simple embarrassment to toxic shame.[27] Emotions have been described as consisting of a coordinated set of responses, which may include verbal, physiological, behavioral, and neural mechanisms.[28]

Emotions have been categorized, with some relationships existing between emotions and some direct opposites existing. Graham differentiates emotions as functional or dysfunctional and argues all functional emotions have benefits.[29]

In some uses of the word, emotions are intense feelings that are directed at someone or something.[30] On the other hand, emotion can be used to refer to states that are mild (as in annoyed or content) and to states that are not directed at anything (as in anxiety and depression). One line of research looks at the meaning of the word emotion in everyday language and finds that this usage is rather different from that in academic discourse.[31]

In practical terms, Joseph LeDoux has defined emotions as the result of a cognitive and conscious process which occurs in response to a body system response to a trigger.[32]

Components

According to Scherer's Component Process Model (CPM) of emotion,[10] there are five crucial elements of emotion. From the component process perspective, emotional experience requires that all of these processes become coordinated and synchronized for a short period of time, driven by appraisal processes. Although the inclusion of cognitive appraisal as one of the elements is slightly controversial, since some theorists make the assumption that emotion and cognition are separate but interacting systems, the CPM provides a sequence of events that effectively describes the coordination involved during an emotional episode.

- Cognitive appraisal: provides an evaluation of events and objects.

- Bodily symptoms: the physiological component of emotional experience.

- Action tendencies: a motivational component for the preparation and direction of motor responses.

- Expression: facial and vocal expression almost always accompanies an emotional state to communicate reaction and intention of actions.

- Feelings: the subjective experience of emotional state once it has occurred.

Differentiation

Emotion can be differentiated from a number of similar constructs within the field of affective neuroscience:[28]

- Emotions: predispositions to a certain type of action in response to a specific stimulus, which produce a cascade of rapid and synchronized physiological and cognitive changes.[9]

- Feeling: not all feelings include emotion, such as the feeling of knowing. In the context of emotion, feelings are best understood as a subjective representation of emotions, private to the individual experiencing them. Emotions are often described as the raw, instinctive responses, while feelings involve our interpretation and awareness of those responses.[33][34][better source needed]

- Moods: enduring affective states that are considered less intense than emotions and appear to lack a contextual stimulus.[30]

- Affect: a broader term used to describe the emotional and cognitive experience of an emotion, feeling or mood. It can be understood as a combination of three components: emotion, mood, and affectivity (an individual's overall disposition or temperament, which can be characterized as having a generally positive or negative affect).

Evolutionary Approach: Emotions' Purpose and Value

There is no single, universally accepted evolutionary theory. The most prominent ideas suggest that emotions have evolved to serve various adaptive functions:[35][36]

- Survival, Threat Detection, Decision-Making, and Motivation. One view is that emotions facilitate adaptive responses to environmental challenges. Emotions like fear, anger, and disgust are thought to have evolved to help humans and other animals detect and respond to threats and dangers in their environment. For example, fear helps individuals react quickly to potential dangers, anger can motivate self-defense or assertiveness, and disgust can protect against harmful substances. While happiness might reinforce behaviors that lead to positive outcomes. For example, the anticipation of the reward associated with a pleasurable emotion like joy can motivate individuals to engage in behaviors that promote their well-being.[37]

- Memory Enhancement: Emotions can enhance memory. Events or experiences that trigger strong emotions are often remembered more vividly, which can be advantageous for learning from past experiences and avoiding potential threats or repeating successful behaviors.

- Social Communication. Emotions play a crucial role in social interactions. Expressing emotions through facial expressions, body language, and vocalizations helps convey information to others about one's internal state. This, in turn, facilitates cooperation, bonding, and the maintenance of social relationships. For example, a smile communicates happiness and friendliness, while a frown may signal distress or disapproval. Emotions can also ignite conversations about values and ethics.[38] However some emotions, such as some forms of anxiety, are sometimes regarded as part of a mental illness and thus possibly of negative value.[39]

Classification

A distinction can be made between emotional episodes and emotional dispositions. Emotional dispositions are also comparable to character traits, where someone may be said to be generally disposed to experience certain emotions. For example, an irritable person is generally disposed to feel irritation more easily or quickly than others do. Finally, some theorists place emotions within a more general category of "affective states" where affective states can also include emotion-related phenomena such as pleasure and pain, motivational states (for example, hunger or curiosity), moods, dispositions and traits.[40]

Basic Emotions Theory

For more than 40 years, Paul Ekman has supported the view that emotions are discrete, measurable, and physiologically distinct. Ekman's most influential work revolved around the finding that certain emotions appeared to be universally recognized, even in cultures that were preliterate and could not have learned associations for facial expressions through media. Another classic study found that when participants contorted their facial muscles into distinct facial expressions (for example, disgust), they reported subjective and physiological experiences that matched the distinct facial expressions. Ekman's facial-expression research examined six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.[41]

Later in his career,[42] Ekman theorized that other universal emotions may exist beyond these six. In light of this, recent cross-cultural studies led by Daniel Cordaro and Dacher Keltner, both former students of Ekman, extended the list of universal emotions. In addition to the original six, these studies provided evidence for amusement, awe, contentment, desire, embarrassment, pain, relief, and sympathy in both facial and vocal expressions. They also found evidence for boredom, confusion, interest, pride, and shame facial expressions, as well as contempt, relief, and triumph vocal expressions.[43][44][45]

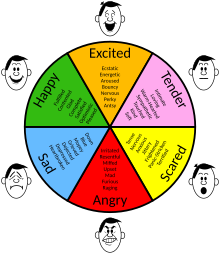

Robert Plutchik agreed with Ekman's biologically driven perspective but developed the "wheel of emotions", suggesting eight primary emotions grouped on a positive or negative basis: joy versus sadness; anger versus fear; trust versus disgust; and surprise versus anticipation.[46] Some basic emotions can be modified to form complex emotions. The complex emotions could arise from cultural conditioning or association combined with the basic emotions. Alternatively, similar to the way primary colors combine, primary emotions could blend to form the full spectrum of human emotional experience. For example, interpersonal anger and disgust could blend to form contempt. Relationships exist between basic emotions, resulting in positive or negative influences.[47]

Jaak Panksepp carved out seven biologically inherited primary affective systems called SEEKING (expectancy), FEAR (anxiety), RAGE (anger), LUST (sexual excitement), CARE (nurturance), PANIC/GRIEF (sadness), and PLAY (social joy). He proposed what is known as "core-SELF" to be generating these affects.[48]

Multi-Dimensional Analysis Theory

Psychologists have used methods such as factor analysis to attempt to map emotion-related responses onto a more limited number of dimensions. Such methods attempt to boil emotions down to underlying dimensions that capture the similarities and differences between experiences.[50] Often, the first two dimensions uncovered by factor analysis are valence (how negative or positive the experience feels) and arousal (how energized or enervated the experience feels). These two dimensions can be depicted on a 2D coordinate map.[4] This two-dimensional map has been theorized to capture one important component of emotion called core affect.[51][52] Core affect is not theorized to be the only component to emotion, but to give the emotion its hedonic and felt energy.

Using statistical methods to analyze emotional states elicited by short videos, Cowen and Keltner identified 27 varieties of emotional experience: admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire and surprise.[53]

Theories

Pre-modern history

In Hinduism, Bharata Muni enunciated the eight rasas (emotions) in the Nātyasāstra, an ancient Sanskrit text of dramatic theory and other performance arts, written between 200 BC and 200 AD.[54] The theory of rasas still forms the aesthetic underpinning of all Indian classical dance and theatre, such as Bharatanatyam, kathak, Kuchipudi, Odissi, Manipuri, Kudiyattam, Kathakali and others.[54] Bharata Muni established the following: Śṛṅgāraḥ (शृङ्गारः): Romance / Love / attractiveness, Hāsyam (हास्यं): Laughter /mirth /comedy, Raudram (रौद्रं): Fury, Kāruṇyam (कारुण्यं): Compassion / mercy. Bībhatsam (बीभत्सं): Disgust / aversion, Bhayānakam (भयानकं): Horror / terror, Veeram (वीरं): Heroism. Adbhutam (अद्भुतं): Surprise/ wonder.[55]

In Buddhism, emotions occur when an object is considered as attractive or repulsive. There is a felt tendency impelling people towards attractive objects and impelling them to move away from repulsive or harmful objects; a disposition to possess the object (greed), to destroy it (hatred), to flee from it (fear), to get obsessed or worried over it (anxiety), and so on.[56]

In Stoic theories, normal emotions (like delight and fear) are described as irrational impulses which come from incorrect appraisals of what is 'good' or 'bad'. Alternatively, there are 'good emotions' (like joy and caution) experienced by those that are wise, which come from correct appraisals of what is 'good' and 'bad'.[57][58]

Aristotle believed that emotions were an essential component of virtue.[59] In the Aristotelian view all emotions (called passions) corresponded to appetites or capacities. During the Middle Ages, the Aristotelian view was adopted and further developed by scholasticism and Thomas Aquinas[60] in particular.

In Chinese antiquity, excessive emotion was believed to cause damage to qi, which in turn, damages the vital organs.[61] The four humors theory made popular by Hippocrates contributed to the study of emotion in the same way that it did for medicine.

In the early 11th century, Avicenna theorized about the influence of emotions on health and behaviors, suggesting the need to manage emotions.[62]

Early modern views on emotion are developed in the works of philosophers such as René Descartes, Niccolò Machiavelli, Baruch Spinoza,[63] Thomas Hobbes[64] and David Hume. In the 19th century emotions were considered adaptive and were studied more frequently from an empiricist psychiatric perspective.

Western theological

Christian perspective on emotion presupposes a theistic origin to humanity. God who created humans gave humans the ability to feel emotion and interact emotionally. Biblical content expresses that God is a person who feels and expresses emotion. Though a somatic view would place the locus of emotions in the physical body, Christian theory of emotions would view the body more as a platform for the sensing and expression of emotions. Therefore, emotions themselves arise from the person, or that which is "imago-dei" or Image of God in humans. In Christian thought, emotions have the potential to be controlled through reasoned reflection. That reasoned reflection also mimics God who made mind. The purpose of emotions in human life is therefore summarized in God's call to enjoy Him and creation, humans are to enjoy emotions and benefit from them and use them to energize behavior.[65][66]

Evolutionary theories

19th century

Perspectives on emotions from evolutionary theory were initiated during the mid-late 19th century with Charles Darwin's 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.[67] Darwin argued that emotions served no evolved purpose for humans, neither in communication, nor in aiding survival.[68] Darwin largely argued that emotions evolved via the inheritance of acquired characters. He pioneered various methods for studying non-verbal expressions, from which he concluded that some expressions had cross-cultural universality. Darwin also detailed homologous expressions of emotions that occur in animals. This led the way for animal research on emotions and the eventual determination of the neural underpinnings of emotion.

Contemporary

More contemporary views along the evolutionary psychology spectrum posit that both basic emotions and social emotions evolved to motivate (social) behaviors that were adaptive in the ancestral environment.[69] Emotion is an essential part of any human decision-making and planning, and the famous distinction made between reason and emotion is not as clear as it seems.[70] Paul D. MacLean claims that emotion competes with even more instinctive responses, on one hand, and the more abstract reasoning, on the other hand. The increased potential in neuroimaging has also allowed investigation into evolutionarily ancient parts of the brain. Important neurological advances were derived from these perspectives in the 1990s by Joseph E. LeDoux and Antonio Damasio. For example, in an extensive study of a subject with ventromedial frontal lobe damage described in the book Descartes' Error, Damasio demonstrated how loss of physiological capacity for emotion resulted in the subject's lost capacity to make decisions despite having robust faculties for rationally assessing options.[71] Research on physiological emotion has caused modern neuroscience to abandon the model of emotions and rationality as opposing forces. In contrast to the ancient Greek ideal of dispassionate reason, the neuroscience of emotion shows that emotion is necessarily integrated with intellect.[72]

Research on social emotion also focuses on the physical displays of emotion including body language of animals and humans (see affect display). For example, spite seems to work against the individual but it can establish an individual's reputation as someone to be feared.[69] Shame and pride can motivate behaviors that help one maintain one's standing in a community, and self-esteem is one's estimate of one's status.[69][73][page needed]

Somatic theories

Somatic theories of emotion claim that bodily responses, rather than cognitive interpretations, are essential to emotions. The first modern version of such theories came from William James in the 1880s. The theory lost favor in the 20th century, but has regained popularity more recently due largely to theorists such as John T. Cacioppo,[74] Antonio Damasio,[75] Joseph E. LeDoux[76] and Robert Zajonc[77] who are able to appeal to neurological evidence.[78]

James–Lange theory

In his 1884 article[79] William James argued that feelings and emotions were secondary to physiological phenomena. In his theory, James proposed that the perception of what he called an "exciting fact" directly led to a physiological response, known as "emotion".[80] To account for different types of emotional experiences, James proposed that stimuli trigger activity in the autonomic nervous system, which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain. The Danish psychologist Carl Lange also proposed a similar theory at around the same time, and therefore this theory became known as the James–Lange theory. As James wrote, "the perception of bodily changes, as they occur, is the emotion." James further claims that "we feel sad because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and either we cry, strike, or tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be."[79]

An example of this theory in action would be as follows: An emotion-evoking stimulus (snake) triggers a pattern of physiological response (increased heart rate, faster breathing, etc.), which is interpreted as a particular emotion (fear). This theory is supported by experiments in which by manipulating the bodily state induces a desired emotional state.[81] Some people may believe that emotions give rise to emotion-specific actions, for example, "I'm crying because I'm sad", or "I ran away because I was scared." The issue with the James–Lange theory is that of causation (bodily states causing emotions and being a priori), not that of the bodily influences on emotional experience (which can be argued and is still quite prevalent today in biofeedback studies and embodiment theory).[82]

Although mostly abandoned in its original form, Tim Dalgleish argues that most contemporary neuroscientists have embraced the components of the James-Lange theory of emotions.[83]

The James–Lange theory has remained influential. Its main contribution is the emphasis it places on the embodiment of emotions, especially the argument that changes in the bodily concomitants of emotions can alter their experienced intensity. Most contemporary neuroscientists would endorse a modified James–Lange view in which bodily feedback modulates the experience of emotion. (p. 583)

Cannon–Bard theory

Walter Bradford Cannon agreed that physiological responses played a crucial role in emotions, but did not believe that physiological responses alone could explain subjective emotional experiences. He argued that physiological responses were too slow and often imperceptible and this could not account for the relatively rapid and intense subjective awareness of emotion.[84] He also believed that the richness, variety, and temporal course of emotional experiences could not stem from physiological reactions, that reflected fairly undifferentiated fight or flight responses.[85][86] An example of this theory in action is as follows: An emotion-evoking event (snake) triggers simultaneously both a physiological response and a conscious experience of an emotion.

Phillip Bard contributed to the theory with his work on animals. Bard found that sensory, motor, and physiological information all had to pass through the diencephalon (particularly the thalamus), before being subjected to any further processing. Therefore, Cannon also argued that it was not anatomically possible for sensory events to trigger a physiological response prior to triggering conscious awareness and emotional stimuli had to trigger both physiological and experiential aspects of emotion simultaneously.[85]

Two-factor theory

Stanley Schachter formulated his theory on the earlier work of a Spanish physician, Gregorio Marañón, who injected patients with epinephrine and subsequently asked them how they felt. Marañón found that most of these patients felt something but in the absence of an actual emotion-evoking stimulus, the patients were unable to interpret their physiological arousal as an experienced emotion. Schachter did agree that physiological reactions played a big role in emotions. He suggested that physiological reactions contributed to emotional experience by facilitating a focused cognitive appraisal of a given physiologically arousing event and that this appraisal was what defined the subjective emotional experience. Emotions were thus a result of two-stage process: general physiological arousal, and experience of emotion. For example, the physiological arousal, heart pounding, in a response to an evoking stimulus, the sight of a bear in the kitchen. The brain then quickly scans the area, to explain the pounding, and notices the bear. Consequently, the brain interprets the pounding heart as being the result of fearing the bear.[4] With his student, Jerome Singer, Schachter demonstrated that subjects can have different emotional reactions despite being placed into the same physiological state with an injection of epinephrine. Subjects were observed to express either anger or amusement depending on whether another person in the situation (a confederate) displayed that emotion. Hence, the combination of the appraisal of the situation (cognitive) and the participants' reception of adrenalin or a placebo together determined the response. This experiment has been criticized in Jesse Prinz's (2004) Gut Reactions.[87]

Cognitive theories

With the two-factor theory now incorporating cognition, several theories began to argue that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts were entirely necessary for an emotion to occur.

Cognitive theories of emotion emphasize that emotions are shaped by how individuals interpret and appraise situations. These theories highlight:

- The role of cognitive appraisals in evaluating the significance of events.

- The subjectivity of emotions and the influence of individual differences.

- The cognitive labeling of emotional experiences.

- The complexity of emotional responses, influenced by cognitive processes, physiological reactions, and situational factors.

These theories acknowledge that emotions are not automatic reactions but result from the interplay of cognitive interpretations, physiological responses, and the social context. A prominent philosophical exponent is Robert C. Solomon (for example, The Passions, Emotions and the Meaning of Life, 1993[88]). Solomon claims that emotions are judgments. He has put forward a more nuanced view which responds to what he has called the 'standard objection' to cognitivism, the idea that a judgment that something is fearsome can occur with or without emotion, so judgment cannot be identified with emotion.

Cognitive Appraisal Theory

One of the main proponents of this view was Richard Lazarus who argued that emotions must have some cognitive intentionality. The cognitive activity involved in the interpretation of an emotional context may be conscious or unconscious and may or may not take the form of conceptual processing.

Lazarus' theory is very influential; emotion is a disturbance that occurs in the following order:

- Cognitive appraisal: The individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion.

- Physiological changes: The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response.

- Action: The individual feels the emotion and chooses how to react.

For example: Jenny sees a snake.

- Jenny cognitively assesses the snake in her presence. Cognition allows her to understand it as a danger.

- Her brain activates the adrenal glands which pump adrenalin through her blood stream, resulting in increased heartbeat.

- Jenny screams and runs away.

Lazarus stressed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes. These processes underline coping strategies that form the emotional reaction by altering the relationship between the person and the environment.

Two-Process Theory

George Mandler provided an extensive theoretical and empirical discussion of emotion as influenced by cognition, consciousness, and the autonomic nervous system in two books (Mind and Emotion, 1975,[89] and Mind and Body: Psychology of Emotion and Stress, 1984[90])

George Mandler, a prominent psychologist known for his contributions to the study of cognition and emotion, proposed the "Two-Process Theory of Emotion". This theory offers insights into how emotions are generated and how cognitive processes play a role in emotional experiences. Mandler's theory focuses on the interplay between primary and secondary appraisal processes in the formation of emotions. Here are the key components of his theory:

- Primary Appraisal: This initial cognitive appraisal involves evaluating a situation for its relevance and implications for one's well-being. It assesses whether a situation is beneficial, harmful, or neutral. A positive primary appraisal may lead to positive emotions, while a negative primary appraisal may lead to negative emotions.

- Secondary Appraisal: Secondary appraisal follows the primary appraisal and involves an assessment of one's ability to cope with or manage the situation. If an individual believes they have the resources and skills to cope effectively, this may result in a different emotional response than if they perceive themselves as unable to cope.

- Emotion Generation: The combination of the primary and secondary appraisals contributes to the generation of emotions. The specific emotion experienced is determined by these appraisals. For instance, if a person appraises a situation as relevant to their well-being (positive or negative) and believes they have the resources to cope, this might lead to an emotion such as joy or relief. Conversely, if the situation is appraised negatively, and coping resources are perceived as lacking, emotions like fear or sadness may result.

Mandler's Two-Process Theory of Emotion emphasizes the importance of cognitive appraisal processes in shaping emotional experiences. It recognizes that emotions are not just automatic reactions but result from complex evaluations of the significance of situations and one's ability to manage them effectively. This theory underscores the role of cognition in the emotional process and highlights the interplay of cognitive factors in the formation of emotions.

The Affect Infusion Model (AIM)

The Affect Infusion Model (AIM) is a psychological framework that was developed by Joseph Forgas in the 1990s. This model focuses on how affect, or mood and emotions, can influence cognitive processes and decision-making. The central idea of the AIM is that affect, whether it's a positive or negative mood, can "infuse" or influence various cognitive activities, including information processing and judgments.

Key components and principles of the Affect Infusion Model include:

- Affect as Information: The AIM posits that individuals use their current mood or emotional state as a source of information when making judgments or decisions. In other words, people consider their emotional experiences as part of the decision-making process.

- Information Processing Strategies: The model suggests that affect can influence the strategies people use to process information. Positive affect might lead to a more heuristic or "top-down" processing style, whereas negative affect might lead to a more systematic, detail-oriented "bottom-up" processing style.

- Affect Congruence: The AIM suggests that when the affective state is congruent with the information being processed, it can enhance processing efficiency and lead to more favorable judgments. For example, a positive mood might lead to more positive evaluations of positive information.

- Affect Infusion: The concept of "affect infusion" refers to the idea that affect can "infuse" or bias cognitive processes, potentially leading to decision-making that is influenced by emotional factors.

- Moderating Factors: The model acknowledges that various factors, such as individual differences, task complexity, and the extent of attention paid to one's mood, can moderate the degree to which affect influences cognition.

The Affect Infusion Model has been applied to a wide range of areas, including consumer behavior, social judgment, and interpersonal interactions. It emphasizes the idea that emotions and mood play a more significant role in cognitive processes and decision-making than traditionally thought. While it has been influential in understanding the interplay between affect and cognition, it is important to note that the AIM is just one of several models in the field of emotion and cognition that help explain the intricate relationship between emotions and thinking.

Appraisal-Tendency Theoryedit

Source:[91]

The Appraisal-Tendency Theory, developed by Joseph P. Forgas, is a theory that focuses on how people have dispositional tendencies to appraise and interpret situations in specific ways, leading to consistent emotional reactions to particular types of situations. This theory suggests that certain individuals may have stable, habitual patterns of appraising and attributing emotional significance to events, and these tendencies can influence their emotional responses and judgments.

Key features and concepts of the Appraisal-Tendency Theory include:

- Cognitive Appraisals: Appraisal tendencies refer to the habitual or characteristic ways that individuals appraise or evaluate situations. Appraisals involve cognitive judgments about the personal relevance, desirability, and significance of events or situations.

- Stable and Individual Differences: The theory posits that these appraisal tendencies are stable and relatively consistent across time. They are also seen as individual differences, meaning that people may differ in the specific appraisal tendencies they exhibit.

- Emotional Responses: Appraisal tendencies influence emotional responses to situations. For instance, individuals with a tendency to appraise situations as threatening may consistently experience fear or anxiety in response to a range of situations perceived as threats.

- Influence on Social Judgments: The theory extends beyond emotions to include the impact of appraisal tendencies on social judgments and evaluations. For example, individuals with a tendency to perceive events as unfair may make consistent social judgments related to fairness and justice.

- Context Dependence: Appraisal tendencies may interact with situational factors. In some situations, the tendency to appraise a situation as threatening, for instance, may lead to fear, while in different contexts, it may not produce the same emotional response.

Appraisal-Tendency Theory suggests that these cognitive tendencies can shape an individual's overall emotional disposition, influencing their emotional reactions and social judgments. This theory has been applied in various contexts, including studies of personality, social psychology, and decision-making, to better understand how cognitive appraisal tendencies influence emotional and evaluative responses.

Laws of Emotionedit

Source:[92]

Nico Frijda was a prominent psychologist known for his work in the field of emotion and affective science. One of the key contributions of Frijda are his "Laws of Emotion", which outline a set of principles that help explain how emotions function and how they are experienced. Frijda's Laws of Emotion are as follows:

- The Law of Situational Meaning: This law posits that emotions are elicited by events or situations that have personal significance and meaning for the individual. Emotions are not random but are a response to the perceived meaning of the situation.

- The Law of Concern: Frijda suggests that emotions are fundamentally concerned with the individual's well-being and adaptation. Emotions serve as signals or reactions to situations that impact one's goals, needs, or values.

- The Law of Appraisal: This law acknowledges the role of cognitive appraisal processes in the emotional experience. Individuals appraise or evaluate a situation based on factors such as its relevance, congruence with goals, and coping potential, which in turn shapes the specific emotional response.

- The Law of Readiness: Frijda's theory suggests that emotions prepare individuals for action. Emotions are associated with physiological changes and action tendencies that ready the individual to respond to the situation. For example, fear may prepare someone to escape a threat.

- The Law of Concerned Expectancy: Emotions are influenced by both what is happening now and what is anticipated to occur in the future. Emotions can reflect an individual's expectations about the consequences of a situation.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk