A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Free will is the capacity or ability to choose between different possible courses of action.[1]

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, and other judgements which apply only to actions that are freely chosen. It is also connected with the concepts of advice, persuasion, deliberation, and prohibition. Traditionally, only actions that are freely willed are seen as deserving credit or blame. Whether free will exists, what it is and the implications of whether it exists or not constitute some of the longest running debates of philosophy. Some conceive of free will as the ability to act beyond the limits of external influences or wishes.

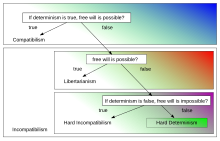

Some conceive free will to be the capacity to make choices undetermined by past events. Determinism suggests that only one course of events is possible, which is inconsistent with a libertarian model of free will.[2] Ancient Greek philosophy identified this issue,[3] which remains a major focus of philosophical debate. The view that posits free will as incompatible with determinism is called incompatibilism and encompasses both metaphysical libertarianism (the claim that determinism is false and thus free will is at least possible) and hard determinism (the claim that determinism is true and thus free will is not possible). Another incompatibilist position is hard incompatibilism, which holds not only determinism but also indeterminism to be incompatible with free will and thus free will to be impossible whatever the case may be regarding determinism.

In contrast, compatibilists hold that free will is compatible with determinism. Some compatibilists even hold that determinism is necessary for free will, arguing that choice involves preference for one course of action over another, requiring a sense of how choices will turn out.[4][5] Compatibilists thus consider the debate between libertarians and hard determinists over free will vs. determinism a false dilemma.[6] Different compatibilists offer very different definitions of what "free will" means and consequently find different types of constraints to be relevant to the issue. Classical compatibilists considered free will nothing more than freedom of action, considering one free of will simply if, had one counterfactually wanted to do otherwise, one could have done otherwise without physical impediment. Many contemporary compatibilists instead identify free will as a psychological capacity, such as to direct one's behavior in a way responsive to reason, and there are still further different conceptions of free will, each with their own concerns, sharing only the common feature of not finding the possibility of determinism a threat to the possibility of free will.[7]

History of free will

The problem of free will has been identified in ancient Greek philosophical literature. The notion of compatibilist free will has been attributed to both Aristotle (4th century BCE) and Epictetus (1st century CE): "it was the fact that nothing hindered us from doing or choosing something that made us have control over them".[3][8] According to Susanne Bobzien, the notion of incompatibilist free will is perhaps first identified in the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias (3rd century CE): "what makes us have control over things is the fact that we are causally undetermined in our decision and thus can freely decide between doing/choosing or not doing/choosing them".

The term "free will" (liberum arbitrium) was introduced by Christian philosophy (4th century CE). It has traditionally meant (until the Enlightenment proposed its own meanings) lack of necessity in human will,[9] so that "the will is free" meant "the will does not have to be such as it is". This requirement was universally embraced by both incompatibilists and compatibilists.[10]

Western philosophy

The underlying questions are whether we have control over our actions, and if so, what sort of control, and to what extent. These questions predate the early Greek stoics (for example, Chrysippus), and some modern philosophers lament the lack of progress over all these centuries.[11][12]

On one hand, humans have a strong sense of freedom, which leads them to believe that they have free will.[13][14] On the other hand, an intuitive feeling of free will could be mistaken.[15][16]

It is difficult to reconcile the intuitive evidence that conscious decisions are causally effective with the view that the physical world can be explained entirely by physical law.[17] The conflict between intuitively felt freedom and natural law arises when either causal closure or physical determinism (nomological determinism) is asserted. With causal closure, no physical event has a cause outside the physical domain, and with physical determinism, the future is determined entirely by preceding events (cause and effect).

The puzzle of reconciling 'free will' with a deterministic universe is known as the problem of free will or sometimes referred to as the dilemma of determinism.[18] This dilemma leads to a moral dilemma as well: the question of how to assign responsibility for actions if they are caused entirely by past events.[19][20]

Compatibilists maintain that mental reality is not of itself causally effective.[21][22] Classical compatibilists have addressed the dilemma of free will by arguing that free will holds as long as humans are not externally constrained or coerced.[23] Modern compatibilists make a distinction between freedom of will and freedom of action, that is, separating freedom of choice from the freedom to enact it.[24] Given that humans all experience a sense of free will, some modern compatibilists think it is necessary to accommodate this intuition.[25][26] Compatibilists often associate freedom of will with the ability to make rational decisions.

A different approach to the dilemma is that of incompatibilists, namely, that if the world is deterministic, then our feeling that we are free to choose an action is simply an illusion. Metaphysical libertarianism is the form of incompatibilism which posits that determinism is false and free will is possible (at least some people have free will).[27] This view is associated with non-materialist constructions,[15] including both traditional dualism, as well as models supporting more minimal criteria; such as the ability to consciously veto an action or competing desire.[28][29] Yet even with physical indeterminism, arguments have been made against libertarianism in that it is difficult to assign Origination (responsibility for "free" indeterministic choices).

Free will here is predominantly treated with respect to physical determinism in the strict sense of nomological determinism, although other forms of determinism are also relevant to free will.[30] For example, logical and theological determinism challenge metaphysical libertarianism with ideas of destiny and fate, and biological, cultural and psychological determinism feed the development of compatibilist models. Separate classes of compatibilism and incompatibilism may even be formed to represent these.[31]

Below are the classic arguments bearing upon the dilemma and its underpinnings.

Incompatibilism

Incompatibilism is the position that free will and determinism are logically incompatible, and that the major question regarding whether or not people have free will is thus whether or not their actions are determined. "Hard determinists", such as d'Holbach, are those incompatibilists who accept determinism and reject free will. In contrast, "metaphysical libertarians", such as Thomas Reid, Peter van Inwagen, and Robert Kane, are those incompatibilists who accept free will and deny determinism, holding the view that some form of indeterminism is true.[32] Another view is that of hard incompatibilists, which state that free will is incompatible with both determinism and indeterminism.[33]

Traditional arguments for incompatibilism are based on an "intuition pump": if a person is like other mechanical things that are determined in their behavior such as a wind-up toy, a billiard ball, a puppet, or a robot, then people must not have free will.[32][34] This argument has been rejected by compatibilists such as Daniel Dennett on the grounds that, even if humans have something in common with these things, it remains possible and plausible that we are different from such objects in important ways.[35]

Another argument for incompatibilism is that of the "causal chain". Incompatibilism is key to the idealist theory of free will. Most incompatibilists reject the idea that freedom of action consists simply in "voluntary" behavior. They insist, rather, that free will means that someone must be the "ultimate" or "originating" cause of his actions. They must be causa sui, in the traditional phrase. Being responsible for one's choices is the first cause of those choices, where first cause means that there is no antecedent cause of that cause. The argument, then, is that if a person has free will, then they are the ultimate cause of their actions. If determinism is true, then all of a person's choices are caused by events and facts outside their control. So, if everything someone does is caused by events and facts outside their control, then they cannot be the ultimate cause of their actions. Therefore, they cannot have free will.[36][37][38] This argument has also been challenged by various compatibilist philosophers.[39][40]

A third argument for incompatibilism was formulated by Carl Ginet in the 1960s and has received much attention in the modern literature. The simplified argument runs along these lines: if determinism is true, then we have no control over the events of the past that determined our present state and no control over the laws of nature. Since we can have no control over these matters, we also can have no control over the consequences of them. Since our present choices and acts, under determinism, are the necessary consequences of the past and the laws of nature, then we have no control over them and, hence, no free will. This is called the consequence argument.[41][42] Peter van Inwagen remarks that C.D. Broad had a version of the consequence argument as early as the 1930s.[43]

The difficulty of this argument for some compatibilists lies in the fact that it entails the impossibility that one could have chosen other than one has. For example, if Jane is a compatibilist and she has just sat down on the sofa, then she is committed to the claim that she could have remained standing, if she had so desired. But it follows from the consequence argument that, if Jane had remained standing, she would have either generated a contradiction, violated the laws of nature or changed the past. Hence, compatibilists are committed to the existence of "incredible abilities", according to Ginet and van Inwagen. One response to this argument is that it equivocates on the notions of abilities and necessities, or that the free will evoked to make any given choice is really an illusion and the choice had been made all along, oblivious to its "decider".[42] David Lewis suggests that compatibilists are only committed to the ability to do something otherwise if different circumstances had actually obtained in the past.[44]

Using T, F for "true" and "false" and ? for undecided, there are exactly nine positions regarding determinism/free will that consist of any two of these three possibilities:[45]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinism D | T | F | T | F | T | F | ? | ? | ? |

| Free will FW | F | T | T | F | ? | ? | F | T | ? |

Incompatibilism may occupy any of the nine positions except (5), (8) or (3), which last corresponds to soft determinism. Position (1) is hard determinism, and position (2) is libertarianism. The position (1) of hard determinism adds to the table the contention that D implies FW is untrue, and the position (2) of libertarianism adds the contention that FW implies D is untrue. Position (9) may be called hard incompatibilism if one interprets ? as meaning both concepts are of dubious value. Compatibilism itself may occupy any of the nine positions, that is, there is no logical contradiction between determinism and free will, and either or both may be true or false in principle. However, the most common meaning attached to compatibilism is that some form of determinism is true and yet we have some form of free will, position (3).[46]

Alex Rosenberg makes an extrapolation of physical determinism as inferred on the macroscopic scale by the behaviour of a set of dominoes to neural activity in the brain where; "If the brain is nothing but a complex physical object whose states are as much governed by physical laws as any other physical object, then what goes on in our heads is as fixed and determined by prior events as what goes on when one domino topples another in a long row of them."[47] Physical determinism is currently disputed by prominent interpretations of quantum mechanics, and while not necessarily representative of intrinsic indeterminism in nature, fundamental limits of precision in measurement are inherent in the uncertainty principle.[48] The relevance of such prospective indeterminate activity to free will is, however, contested,[49] even when chaos theory is introduced to magnify the effects of such microscopic events.[29][50]

Below these positions are examined in more detail.[45]

Hard determinism

Determinism can be divided into causal, logical and theological determinism.[51] Corresponding to each of these different meanings, there arises a different problem for free will.[52] Hard determinism is the claim that determinism is true, and that it is incompatible with free will, so free will does not exist. Although hard determinism generally refers to nomological determinism (see causal determinism below), it can include all forms of determinism that necessitate the future in its entirety.[53] Relevant forms of determinism include:

- Causal determinism

- The idea that everything is caused by prior conditions, making it impossible for anything else to happen.[54] In its most common form, nomological (or scientific) determinism, future events are necessitated by past and present events combined with the laws of nature. Such determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace's demon. Imagine an entity that knows all facts about the past and the present, and knows all natural laws that govern the universe. If the laws of nature were determinate, then such an entity would be able to use this knowledge to foresee the future, down to the smallest detail.[55][56]

- Logical determinism

- The notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present or future, are either true or false. The problem of free will, in this context, is the problem of how choices can be free, given that what one does in the future is already determined as true or false in the present.[52]

- Theological determinism

- The idea that the future is already determined, either by a creator deity decreeing or knowing its outcome in advance.[57][58] The problem of free will, in this context, is the problem of how our actions can be free if there is a being who has determined them for us in advance, or if they are already set in time.

Other forms of determinism are more relevant to compatibilism, such as biological determinism, the idea that all behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by our genetic endowment and our biochemical makeup, the latter of which is affected by both genes and environment, cultural determinism and psychological determinism.[52] Combinations and syntheses of determinist theses, such as bio-environmental determinism, are even more common.

Suggestions have been made that hard determinism need not maintain strict determinism, where something near to, like that informally known as adequate determinism, is perhaps more relevant.[30] Despite this, hard determinism has grown less popular in present times, given scientific suggestions that determinism is false – yet the intention of their position is sustained by hard incompatibilism.[27]

Metaphysical libertarianism

One kind of incompatibilism, metaphysical libertarianism holds onto a concept of free will that requires that the agent be able to take more than one possible course of action under a given set of circumstances.[62]

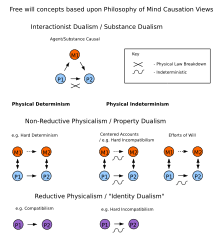

Accounts of libertarianism subdivide into non-physical theories and physical or naturalistic theories. Non-physical theories hold that the events in the brain that lead to the performance of actions do not have an entirely physical explanation, which requires that the world is not closed under physics. This includes interactionist dualism, which claims that some non-physical mind, will, or soul overrides physical causality. Physical determinism implies there is only one possible future and is therefore not compatible with libertarian free will. As consequent of incompatibilism, metaphysical libertarian explanations that do not involve dispensing with physicalism require physical indeterminism, such as probabilistic subatomic particle behavior – theory unknown to many of the early writers on free will. Incompatibilist theories can be categorised based on the type of indeterminism they require; uncaused events, non-deterministically caused events, and agent/substance-caused events.[59]

Non-causal theories

Non-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will do not require a free action to be caused by either an agent or a physical event. They either rely upon a world that is not causally closed, or physical indeterminism. Non-causal accounts often claim that each intentional action requires a choice or volition – a willing, trying, or endeavoring on behalf of the agent (such as the cognitive component of lifting one's arm).[63][64] Such intentional actions are interpreted as free actions. It has been suggested, however, that such acting cannot be said to exercise control over anything in particular. According to non-causal accounts, the causation by the agent cannot be analysed in terms of causation by mental states or events, including desire, belief, intention of something in particular, but rather is considered a matter of spontaneity and creativity. The exercise of intent in such intentional actions is not that which determines their freedom – intentional actions are rather self-generating. The "actish feel" of some intentional actions do not "constitute that event's activeness, or the agent's exercise of active control", rather they "might be brought about by direct stimulation of someone's brain, in the absence of any relevant desire or intention on the part of that person".[59] Another question raised by such non-causal theory, is how an agent acts upon reason, if the said intentional actions are spontaneous.

Some non-causal explanations involve invoking panpsychism, the theory that a quality of mind is associated with all particles, and pervades the entire universe, in both animate and inanimate entities.

Event-causal theories

Event-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will typically rely upon physicalist models of mind (like those of the compatibilist), yet they presuppose physical indeterminism, in which certain indeterministic events are said to be caused by the agent. A number of event-causal accounts of free will have been created, referenced here as deliberative indeterminism, centred accounts, and efforts of will theory.[59] The first two accounts do not require free will to be a fundamental constituent of the universe. Ordinary randomness is appealed to as supplying the "elbow room" that libertarians believe necessary. A first common objection to event-causal accounts is that the indeterminism could be destructive and could therefore diminish control by the agent rather than provide it (related to the problem of origination). A second common objection to these models is that it is questionable whether such indeterminism could add any value to deliberation over that which is already present in a deterministic world.

Deliberative indeterminism asserts that the indeterminism is confined to an earlier stage in the decision process.[65][66] This is intended to provide an indeterminate set of possibilities to choose from, while not risking the introduction of luck (random decision making). The selection process is deterministic, although it may be based on earlier preferences established by the same process. Deliberative indeterminism has been referenced by Daniel Dennett[67] and John Martin Fischer.[68] An obvious objection to such a view is that an agent cannot be assigned ownership over their decisions (or preferences used to make those decisions) to any greater degree than that of a compatibilist model.

Centred accounts propose that for any given decision between two possibilities, the strength of reason will be considered for each option, yet there is still a probability the weaker candidate will be chosen.[60][69][70][71][72][73][74] An obvious objection to such a view is that decisions are explicitly left up to chance, and origination or responsibility cannot be assigned for any given decision.

Efforts of will theory is related to the role of will power in decision making. It suggests that the indeterminacy of agent volition processes could map to the indeterminacy of certain physical events – and the outcomes of these events could therefore be considered caused by the agent. Models of volition have been constructed in which it is seen as a particular kind of complex, high-level process with an element of physical indeterminism. An example of this approach is that of Robert Kane, where he hypothesizes that "in each case, the indeterminism is functioning as a hindrance or obstacle to her realizing one of her purposes – a hindrance or obstacle in the form of resistance within her will which must be overcome by effort."[29] According to Robert Kane such "ultimate responsibility" is a required condition for free will.[75] An important factor in such a theory is that the agent cannot be reduced to physical neuronal events, but rather mental processes are said to provide an equally valid account of the determination of outcome as their physical processes (see non-reductive physicalism).

Although at the time quantum mechanics (and physical indeterminism) was only in the initial stages of acceptance, in his book Miracles: A preliminary study C.S. Lewis stated the logical possibility that if the physical world were proved indeterministic this would provide an entry point to describe an action of a non-physical entity on physical reality.[76] Indeterministic physical models (particularly those involving quantum indeterminacy) introduce random occurrences at an atomic or subatomic level. These events might affect brain activity, and could seemingly allow incompatibilist free will if the apparent indeterminacy of some mental processes (for instance, subjective perceptions of control in conscious volition) map to the underlying indeterminacy of the physical construct. This relationship, however, requires a causative role over probabilities that is questionable,[77] and it is far from established that brain activity responsible for human action can be affected by such events. Secondarily, these incompatibilist models are dependent upon the relationship between action and conscious volition, as studied in the neuroscience of free will. It is evident that observation may disturb the outcome of the observation itself, rendering limited our ability to identify causality.[48] Niels Bohr, one of the main architects of quantum theory, suggested, however, that no connection could be made between indeterminism of nature and freedom of will.[49]

Agent/substance-causal theories

Agent/substance-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will rely upon substance dualism in their description of mind. The agent is assumed power to intervene in the physical world.[78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85] Agent (substance)-causal accounts have been suggested by both George Berkeley[86] and Thomas Reid.[87] It is required that what the agent causes is not causally determined by prior events. It is also required that the agent's causing of that event is not causally determined by prior events. A number of problems have been identified with this view. Firstly, it is difficult to establish the reason for any given choice by the agent, which suggests they may be random or determined by luck (without an underlying basis for the free will decision). Secondly, it has been questioned whether physical events can be caused by an external substance or mind – a common problem associated with interactionalist dualism.

Hard incompatibilism

Hard incompatibilism is the idea that free will cannot exist, whether the world is deterministic or not. Derk Pereboom has defended hard incompatibilism, identifying a variety of positions where free will is irrelevant to indeterminism/determinism, among them the following:

- Determinism (D) is true, D does not imply we lack free will (F), but in fact we do lack F.

- D is true, D does not imply we lack F, but in fact we don't know if we have F.

- D is true, and we do have F.

- D is true, we have F, and F implies D.

- D is unproven, but we have F.

- D isn't true, we do have F, and would have F even if D were true.

- D isn't true, we don't have F, but F is compatible with D.

- Derk Pereboom, Living without Free Will,[33] p. xvi.

Pereboom calls positions 3 and 4 soft determinism, position 1 a form of hard determinism, position 6 a form of classical libertarianism, and any position that includes having F as compatibilism.

John Locke denied that the phrase "free will" made any sense (compare with theological noncognitivism, a similar stance on the existence of God). He also took the view that the truth of determinism was irrelevant. He believed that the defining feature of voluntary behavior was that individuals have the ability to postpone a decision long enough to reflect or deliberate upon the consequences of a choice: "...the will in truth, signifies nothing but a power, or ability, to prefer or choose".[88]

The contemporary philosopher Galen Strawson agrees with Locke that the truth or falsity of determinism is irrelevant to the problem.[89] He argues that the notion of free will leads to an infinite regress and is therefore senseless. According to Strawson, if one is responsible for what one does in a given situation, then one must be responsible for the way one is in certain mental respects. But it is impossible for one to be responsible for the way one is in any respect. This is because to be responsible in some situation S, one must have been responsible for the way one was at S−1. To be responsible for the way one was at S−1, one must have been responsible for the way one was at S−2, and so on. At some point in the chain, there must have been an act of origination of a new causal chain. But this is impossible. Man cannot create himself or his mental states ex nihilo. This argument entails that free will itself is absurd, but not that it is incompatible with determinism. Strawson calls his own view "pessimism" but it can be classified as hard incompatibilism.[89]

Causal determinism

Causal determinism is the concept that events within a given paradigm are bound by causality in such a way that any state (of an object or event) is completely determined by prior states. Causal determinism proposes that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. Causal determinists believe that there is nothing uncaused or self-caused. The most common form of causal determinism is nomological determinism (or scientific determinism), the notion that the past and the present dictate the future entirely and necessarily by rigid natural laws, that every occurrence results inevitably from prior events. Quantum mechanics poses a serious challenge to this view.

Fundamental debate continues over whether the physical universe is likely to be deterministic. Although the scientific method cannot be used to rule out indeterminism with respect to violations of causal closure, it can be used to identify indeterminism in natural law. Interpretations of quantum mechanics at present are both deterministic and indeterministic, and are being constrained by ongoing experimentation.[90]

Destiny and fate

Destiny or fate is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual. It is a concept based on the belief that there is a fixed natural order to the cosmos.

Although often used interchangeably, the words "fate" and "destiny" have distinct connotations.

Fate generally implies there is a set course that cannot be deviated from, and over which one has no control. Fate is related to determinism, but makes no specific claim of physical determinism. Even with physical indeterminism an event could still be fated externally (see for instance theological determinism). Destiny likewise is related to determinism, but makes no specific claim of physical determinism. Even with physical indeterminism an event could still be destined to occur.

Destiny implies there is a set course that cannot be deviated from, but does not of itself make any claim with respect to the setting of that course (i.e., it does not necessarily conflict with incompatibilist free will). Free will if existent could be the mechanism by which that destined outcome is chosen (determined to represent destiny).[91]

Logical determinism

Discussion regarding destiny does not necessitate the existence of supernatural powers. Logical determinism or determinateness is the notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present, or future, are either true or false. This creates a unique problem for free will given that propositions about the future already have a truth value in the present (that is it is already determined as either true or false), and is referred to as the problem of future contingents.

Omniscience

Omniscience is the capacity to know everything that there is to know (included in which are all future events), and is a property often attributed to a creator deity. Omniscience implies the existence of destiny. Some authors have claimed that free will cannot coexist with omniscience. One argument asserts that an omniscient creator not only implies destiny but a form of high level predeterminism such as hard theological determinism or predestination – that they have independently fixed all events and outcomes in the universe in advance. In such a case, even if an individual could have influence over their lower level physical system, their choices in regard to this cannot be their own, as is the case with libertarian free will. Omniscience features as an incompatible-properties argument for the existence of God, known as the argument from free will, and is closely related to other such arguments, for example the incompatibility of omnipotence with a good creator deity (i.e. if a deity knew what they were going to choose, then they are responsible for letting them choose it).

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Freedom_(philosophy)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk