A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Indian Rebellion of 1857 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

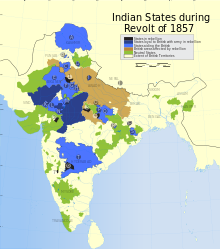

A 1912 map of Northern India, showing the centres of the rebellion. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

The Earl Canning Dhir Shamsher Rana[1] | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

6,000 British killed, including civilians[a][2] Based on a rough comparison of the sketchy pre-1857 regional demographic data and the first 1871 Census of India, probably 800,000 Indians were killed, and very likely more, both in the rebellion and in the famines and epidemics of disease that were caused as a result in its immediate aftermath.[2] | |||||||||

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown.[4][5] The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the form of a mutiny of sepoys of the company's army in the garrison town of Meerut, 40 mi (64 km) northeast of Delhi. It then erupted into other mutinies and civilian rebellions chiefly in the upper Gangetic plain and central India,[b][6][c][7] though incidents of revolt also occurred farther north and east.[d][8] The rebellion posed a military threat to British power in that region,[e][9] and was contained only with the rebels' defeat in Gwalior on 20 June 1858.[10] On 1 November 1858, the British granted amnesty to all rebels not involved in murder, though they did not declare the hostilities to have formally ended until 8 July 1859.

The name of the revolt is contested, and it is variously described as the Sepoy Mutiny, the Indian Mutiny, the Great Rebellion, the Revolt of 1857, the Indian Insurrection, and the First War of Independence.[f][11]

The Indian rebellion was fed by resentments born of diverse perceptions, including invasive British-style social reforms, harsh land taxes, summary treatment of some rich landowners and princes,[12][13] and scepticism about the improvements brought about by British rule.[g][14] Many Indians rose against the British; however, many also fought for the British, and the majority remained seemingly compliant to British rule.[h][14] Violence, which sometimes betrayed exceptional cruelty, was inflicted on both sides, on British officers, and civilians, including women and children, by the rebels, and on the rebels, and their supporters, including sometimes entire villages, by British reprisals; the cities of Delhi and Lucknow were laid waste in the fighting and the British retaliation.[i][14]

After the outbreak of the mutiny in Meerut, the rebels quickly reached Delhi, whose 81-year-old Mughal ruler, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was declared the Emperor of Hindustan. Soon, the rebels had captured large tracts of the North-Western Provinces and Awadh (Oudh). The East India Company's response came rapidly as well. With help from reinforcements, Kanpur was retaken by mid-July 1857, and Delhi by the end of September.[10] However, it then took the remainder of 1857 and the better part of 1858 for the rebellion to be suppressed in Jhansi, Lucknow, and especially the Awadh countryside.[10] Other regions of Company-controlled India—Bengal province, the Bombay Presidency, and the Madras Presidency—remained largely calm.[j][7][10] In the Punjab, the Sikh princes crucially helped the British by providing both soldiers and support.[k][7][10] The large princely states, Hyderabad, Mysore, Travancore, and Kashmir, as well as the smaller ones of Rajputana, did not join the rebellion, serving the British, in the Governor-General Lord Canning's words, as "breakwaters in a storm".[15]

In some regions, most notably in Awadh, the rebellion took on the attributes of a patriotic revolt against British oppression.[16] However, the rebel leaders proclaimed no articles of faith that presaged a new political system.[l][17] Even so, the rebellion proved to be an important watershed in Indian and British Empire history.[m][11][18] It led to the dissolution of the East India Company, and forced the British to reorganize the army, the financial system, and the administration in India, through passage of the Government of India Act 1858.[19] India was thereafter administered directly by the British government in the new British Raj.[15] On 1 November 1858, Queen Victoria issued a proclamation to Indians, which while lacking the authority of a constitutional provision,[n][20] promised rights similar to those of other British subjects.[o][p][21] In the following decades, when admission to these rights was not always forthcoming, Indians were to pointedly refer to the Queen's proclamation in growing avowals of a new nationalism.[q][r][23]

East India Company's expansion in India

Although the British East India Company had established a presence in India as far back as 1612,[24] and earlier administered the factory areas established for trading purposes, its victory in the Battle of Plassey in 1757 marked the beginning of its firm foothold in eastern India. The victory was consolidated in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar, when the East India Company army defeated Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II. After his defeat, the emperor granted the company the right to the "collection of Revenue" in the provinces of Bengal (modern day Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha), known as "Diwani" to the company.[25] The Company soon expanded its territories around its bases in Bombay and Madras; later, the Anglo-Mysore Wars (1766–1799) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars (1772–1818) led to control of even more of India.[26]

In 1806, the Vellore Mutiny was sparked by new uniform regulations that created resentment amongst both Hindu and Muslim sepoys.[27]

After the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Wellesley began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories. This was achieved either by subsidiary alliances between the company and local rulers or by direct military annexation.[28] The subsidiary alliances created the princely states of the Hindu maharajas and the Muslim nawabs. Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir were annexed after the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the 1846 Treaty of Amritsar to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu and thereby became a princely state. The border dispute between Nepal and British India, which sharpened after 1801, had caused the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814–16 and brought the defeated Gurkhas under British influence. In 1854, Berar was annexed, and the state of Oudh was added two years later. For practical purposes, the company was the government of much of India.[citation needed]

Causes of the rebellion

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 occurred as the result of an accumulation of factors over time, rather than any single event.[citation needed]

The sepoys were Indian soldiers who were recruited into the company's army. Just before the rebellion, there were over 300,000 sepoys in the army, compared to about 50,000 British. The East India Company's forces were divided into three presidency armies: Bombay, Madras, and Bengal. The Bengal Army recruited higher castes, such as Brahmins, Rajputs and Bhumihar, mostly from the Awadh and Bihar regions, and even restricted the enlistment of lower castes in 1855.[29] In contrast, the Madras Army and Bombay Army were "more localized, caste-neutral armies" that "did not prefer high-caste men".[30] The domination of higher castes in the Bengal Army has been blamed in part for initial mutinies that led to the rebellion.[citation needed]

In 1772, when Warren Hastings was appointed Fort William's first Governor-General, one of his first undertakings was the rapid expansion of the company's army. Since the sepoys from Bengal – many of whom had fought against the Company in the Battles of Plassey and Buxar – were now suspect in British eyes, Hastings recruited farther west from the high-caste rural Rajputs and Bhumihar of Awadh and Bihar, a practice that continued for the next 75 years. However, in order to forestall any social friction, the company also took action to adapt its military practices to the requirements of their religious rituals. Consequently, these soldiers dined in separate facilities; in addition, overseas service, considered polluting to their caste, was not required of them, and the army soon came officially to recognise Hindu festivals. "This encouragement of high caste ritual status, however, left the government vulnerable to protest, even mutiny, whenever the sepoys detected infringement of their prerogatives."[31] Stokes argues that "The British scrupulously avoided interference with the social structure of the village community which remained largely intact."[32]

After the annexation of Oudh (Awadh) by the East India Company in 1856, many sepoys were disquieted both from losing their perquisites, as landed gentry, in the Oudh courts, and from the anticipation of any increased land-revenue payments that the annexation might bring about.[33] Other historians have stressed that by 1857, some Indian soldiers, interpreting the presence of missionaries as a sign of official intent, were convinced that the company was masterminding mass conversions of Hindus and Muslims to Christianity.[34] Although earlier in the 1830s, evangelicals such as William Carey and William Wilberforce had successfully clamoured for the passage of social reform, such as the abolition of sati and allowing the remarriage of Hindu widows, there is little evidence that the sepoys' allegiance was affected by this.[33]

However, changes in the terms of their professional service may have created resentment. As the extent of the East India Company's jurisdiction expanded with victories in wars or annexation, the soldiers were now expected not only to serve in less familiar regions, such as in Burma, but also to make do without the "foreign service" remuneration that had previously been their due.[35]

A major cause of resentment that arose ten months prior to the outbreak of the rebellion was the General Service Enlistment Act of 25 July 1856. As noted above, men of the Bengal Army had been exempted from overseas service. Specifically, they were enlisted only for service in territories to which they could march. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie saw this as an anomaly, since all sepoys of the Madras and Bombay Armies and the six "General Service" battalions of the Bengal Army had accepted an obligation to serve overseas if required. As a result, the burden of providing contingents for active service in Burma, readily accessible only by sea, and China had fallen disproportionately on the two smaller Presidency Armies. As signed into effect by Lord Canning, Dalhousie's successor as Governor-General, the act required only new recruits to the Bengal Army to accept a commitment for general service. However, serving high-caste sepoys were fearful that it would be eventually extended to them, as well as preventing sons following fathers into an army with a strong tradition of family service.[36]: 261

There were also grievances over the issue of promotions, based on seniority. This, as well as the increasing number of British officers in the battalions,[37][better source needed] made promotion slow, and many Indian officers did not reach commissioned rank until they were too old to be effective.[38]

The Enfield rifle

The final spark was provided by the ammunition for the new Enfield Pattern 1853 rifled musket.[39] These rifles, which fired Minié balls, had a tighter fit than the earlier muskets, and used paper cartridges that came pre-greased. To load the rifle, sepoys had to bite the cartridge open to release the powder.[40] The grease used on these cartridges was rumoured to include tallow derived from beef, which would be offensive to Hindus,[41] and lard derived from pork, which would be offensive to Muslims. At least one Company official pointed out the difficulties this might cause:

unless it be proven that the grease employed in these cartridges is not of a nature to offend or interfere with the prejudices of religion, it will be expedient not to issue them for test to Native corps.[42]

However, in August 1856, greased cartridge production was initiated at Fort William, Calcutta, following a British design. The grease used included tallow supplied by the Indian firm of Gangadarh Banerji & Co.[43] By January, rumours abounded that the Enfield cartridges were greased with animal fat.[citation needed]

Company officers became aware of the rumours through reports of an altercation between a high-caste sepoy and a low-caste labourer at Dum Dum.[44] The labourer had taunted the sepoy that by biting the cartridge, he had himself lost caste, although at this time such cartridges had been issued only at Meerut and not at Dum Dum.[45] There had been rumours that the British sought to destroy the religions of the Indian people, and forcing the native soldiers to break their sacred code would have certainly added to this rumour, as it apparently did. The company was quick to reverse the effects of this policy in hopes that the unrest would be quelled.[46][47]

On 27 January, Colonel Richard Birch, the Military Secretary, ordered that all cartridges issued from depots were to be free from grease, and that sepoys could grease them themselves using whatever mixture "they may prefer".[48] A modification was also made to the drill for loading so that the cartridge was torn with the hands and not bitten. This, however, merely caused many sepoys to be convinced that the rumours were true and that their fears were justified. Additional rumours started that the paper in the new cartridges, which was glazed and stiffer than the previously used paper, was impregnated with grease.[49] In February, a court of inquiry was held at Barrackpore to get to the bottom of these rumours. Native soldiers called as witnesses complained of the paper "being stiff and like cloth in the mode of tearing", said that when the paper was burned it smelled of grease, and announced that the suspicion that the paper itself contained grease could not be removed from their minds.[50]

Civilian disquiet

Civilian rebellion was more multifarious. The rebels consisted of three groups: the feudal nobility, rural landlords called taluqdars, and the peasants. The nobility, many of whom had lost titles and domains under the Doctrine of Lapse, which refused to recognise the adopted children of princes as legal heirs, felt that the company had interfered with a traditional system of inheritance. Rebel leaders such as Nana Sahib and the Rani of Jhansi belonged to this group; the latter, for example, was prepared to accept East India Company supremacy if her adopted son was recognised as her late husband's heir.[51] In other areas of central India, such as Indore and Saugar, where such loss of privilege had not occurred, the princes remained loyal to the company, even in areas where the sepoys had rebelled.[52] The second group, the taluqdars, had lost half their landed estates to peasant farmers as a result of the land reforms that came in the wake of annexation of Oudh. It is mentioned that throughout Oudh, Bihar Rajput Taluqdars provided the bulk of leadership and played an important role during 1857 in the region.[53] As the rebellion gained ground, the taluqdars quickly reoccupied the lands they had lost, and paradoxically, in part because of ties of kinship and feudal loyalty, did not experience significant opposition from the peasant farmers, many of whom joined the rebellion, to the great dismay of the British.[54] It has also been suggested that heavy land-revenue assessment in some areas by the British resulted in many landowning families either losing their land or going into great debt to money lenders, and providing ultimately a reason to rebel; money lenders, in addition to the company, were particular objects of the rebels' animosity.[55] The civilian rebellion was also highly uneven in its geographic distribution, even in areas of north-central India that were no longer under British control. For example, the relatively prosperous Muzaffarnagar district, a beneficiary of a Company irrigation scheme, and next door to Meerut, where the upheaval began, stayed relatively calm throughout.[56]

-

Charles Canning, the Governor-General of India during the rebellion.

-

Lord Dalhousie, the Governor-General of India from 1848 to 1856, who devised the Doctrine of Lapse.

-

Lakshmibai, the Rani of Maratha-ruled Jhansi, one of the principal leaders of the rebellion who earlier had lost her kingdom as a result of the Doctrine of Lapse.

-

Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal Emperor, crowned Emperor of India, by the Indian troops, he was deposed by the British, and died in exile in Burma

"Utilitarian and evangelical-inspired social reform",[57] including the abolition of sati[58][59] and the legalisation of widow remarriage were considered by many—especially the British themselves[60]—to have caused suspicion that Indian religious traditions were being "interfered with", with the ultimate aim of conversion.[60][61] Recent historians, including Chris Bayly, have preferred to frame this as a "clash of knowledges", with proclamations from religious authorities before the revolt and testimony after it including on such issues as the "insults to women", the rise of "low persons under British tutelage", the "pollution" caused by Western medicine and the persecuting and ignoring of traditional astrological authorities.[62] British-run schools were also a problem: according to recorded testimonies, anger had spread because of stories that mathematics was replacing religious instruction, stories were chosen that would "bring contempt" upon Indian religions, and because girl children were exposed to "moral danger" by education.[62]

The justice system was considered to be inherently unfair to the Indians. The official Blue Books, East India (Torture) 1855–1857, laid before the House of Commons during the sessions of 1856 and 1857, revealed that Company officers were allowed an extended series of appeals if convicted or accused of brutality or crimes against Indians.[citation needed]

The economic policies of the East India Company were also resented by many Indians.[63]

The Bengal Army

Each of the three "Presidencies" into which the East India Company divided India for administrative purposes maintained their own armies. Of these, the Army of the Bengal Presidency was the largest. Unlike the other two, it recruited heavily from among high-caste Hindus and comparatively wealthy Muslims. The Muslims formed a larger percentage of the 18 irregular cavalry units[64] within the Bengal Army, whilst Hindus were mainly to be found in the 84 regular infantry and cavalry regiments. Thus 75% of the cavalry regiments was composed of Indian Muslims, while 80% of the infantry was composed of Hindus.[65] The sepoys were therefore affected to a large degree by the concerns of the landholding and traditional members of Indian society. In the early years of Company rule, it tolerated and even encouraged the caste privileges and customs within the Bengal Army, which recruited its regular infantry soldiers almost exclusively amongst the landowning Rajputs and Brahmins of the Bihar and Awadh regions. These soldiers were known as Purbiyas. By the time these customs and privileges came to be threatened by modernising regimes in Calcutta from the 1840s onwards, the sepoys had become accustomed to very high ritual status and were extremely sensitive to suggestions that their caste might be polluted.[66][29]

The sepoys also gradually became dissatisfied with various other aspects of army life. Their pay was relatively low and after Awadh and the Punjab were annexed, the soldiers no longer received extra pay (batta or bhatta) for service there, because they were no longer considered "foreign missions". The junior British officers became increasingly estranged from their soldiers, in many cases treating them as their racial inferiors. In 1856, a new Enlistment Act was introduced by the company, which in theory made every unit in the Bengal Army liable to service overseas. Although it was intended to apply only to new recruits, the serving sepoys feared that the Act might be applied retroactively to them as well.[67] A high-caste Hindu who travelled in the cramped conditions of a wooden troop ship could not cook his own food on his own fire, and accordingly risked losing caste through ritual pollution.[36]: 243

Onset of the rebellion

Several months of increasing tensions coupled with various incidents preceded the actual rebellion. On 26 February 1857 the 19th Bengal Native Infantry (BNI) regiment became concerned that new cartridges they had been issued were wrapped in paper greased with cow and pig fat, which had to be opened by mouth thus affecting their religious sensibilities. Their Colonel confronted them supported by artillery and cavalry on the parade ground, but after some negotiation withdrew the artillery, and cancelled the next morning's parade.[68]

Mangal Pandey

On 29 March 1857 at the Barrackpore parade ground, near Calcutta, 29-year-old Mangal Pandey of the 34th BNI, angered by the recent actions of the East India Company, declared that he would rebel against his commanders. Informed about Pandey's behaviour Sergeant-Major James Hewson went to investigate, only to have Pandey shoot at him. Hewson raised the alarm.[69] When his adjutant Lt. Henry Baugh came out to investigate the unrest, Pandey opened fire but hit Baugh's horse instead.[70]

General John Hearsey came out to the parade ground to investigate, and claimed later that Mangal Pandey was in some kind of "religious frenzy". He ordered the Indian commander of the quarter guard Jemadar Ishwari Prasad to arrest Mangal Pandey, but the Jemadar refused. The quarter guard and other sepoys present, with the single exception of a soldier called Shaikh Paltu, drew back from restraining or arresting Mangal Pandey. Shaikh Paltu restrained Pandey from continuing his attack.[70][71]

After failing to incite his comrades into an open and active rebellion, Mangal Pandey tried to take his own life, by placing his musket to his chest and pulling the trigger with his toe. He managed only to wound himself. He was court-martialled on 6 April and hanged two days later.[citation needed]

The Jemadar Ishwari Prasad was sentenced to death and hanged on 21 April. The regiment was disbanded and stripped of its uniforms because it was felt that it harboured ill-feelings towards its superiors, particularly after this incident. Shaikh Paltu was promoted to the rank of havildar in the Bengal Army but was murdered shortly before the 34th BNI dispersed.[72]

Sepoys in other regiments thought these punishments were harsh. The demonstration of disgrace during the formal disbanding helped foment the rebellion in view of some historians. Disgruntled ex-sepoys returned home to Awadh with a desire for revenge.[citation needed]

Unrest during April 1857

During April, there was unrest and fires at Agra, Allahabad and Ambala. At Ambala in particular, which was a large military cantonment where several units had been collected for their annual musketry practice, it was clear to General Anson, Commander-in-Chief of the Bengal Army, that some sort of rebellion over the cartridges was imminent. Despite the objections of the civilian Governor-General's staff, he agreed to postpone the musketry practice and allow a new drill by which the soldiers tore the cartridges with their fingers rather than their teeth. However, he issued no general orders making this standard practice throughout the Bengal Army and, rather than remain at Ambala to defuse or overawe potential trouble, he then proceeded to Simla, the cool hill station where many high officials spent the summer.[citation needed]

Although there was no open revolt at Ambala, there was widespread arson during late April. Barrack buildings (especially those belonging to soldiers who had used the Enfield cartridges) and British officers' bungalows were set on fire.[73]

Meerut

At Meerut, a large military cantonment, 2,357 Indian sepoys and 2,038 British soldiers were stationed along with 12 British-manned guns. The station held one of the largest concentrations of British troops in India and this was later to be cited as evidence that the original rising was a spontaneous outbreak rather than a pre-planned plot.[36]: 278

Although the state of unrest within the Bengal Army was well known, on 24 April Lieutenant Colonel George Carmichael-Smyth, the unsympathetic commanding officer of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, which was composed mainly of Indian Muslims,[74] ordered 90 of his men to parade and perform firing drills. All except five of the men on parade refused to accept their cartridges. On 9 May, the remaining 85 men were court martialled, and most were sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment with hard labour. Eleven comparatively young soldiers were given five years' imprisonment. The entire garrison was paraded and watched as the condemned men were stripped of their uniforms and placed in shackles. As they were marched off to jail, the condemned soldiers berated their comrades for failing to support them.[citation needed]

The next day was Sunday. Some Indian soldiers warned off-duty junior British officers that plans were afoot to release the imprisoned soldiers by force, but the senior officers to whom this was reported took no action. There was also unrest in the city of Meerut itself, with angry protests in the bazaar and some buildings being set on fire. In the evening, most British officers were preparing to attend church, while many of the British soldiers were off duty and had gone into canteens or into the bazaar in Meerut. The Indian troops, led by the 3rd Cavalry, broke into revolt. British junior officers who attempted to quell the first outbreaks were killed by the rebels. British officers' and civilians' quarters were attacked, and four civilian men, eight women and eight children were killed. Crowds in the bazaar attacked off-duty soldiers there. About 50 Indian civilians, some of them officers' servants who tried to defend or conceal their employers, were killed by the sepoys.[75] While the action of the sepoys in freeing their 85 imprisoned comrades appears to have been spontaneous, some civilian rioting in the city was reportedly encouraged by kotwal (local police commander) Dhan Singh Gurjar.[76]

Some sepoys (especially from the 11th Bengal Native Infantry) escorted trusted British officers and women and children to safety before joining the revolt.[77] Some officers and their families escaped to Rampur, where they found refuge with the Nawab.[citation needed]

The British historian Philip Mason notes that it was inevitable that most of the sepoys and sowars from Meerut should have made for Delhi on the night of 10 May. It was a strong walled city located only forty miles away, it was the ancient capital and present seat of the nominal Mughal Emperor and finally there were no British troops in garrison there in contrast to Meerut.[36]: 278 No effort was made to pursue them.[citation needed]

Delhi

Early on 11 May, the first parties of the 3rd Cavalry reached Delhi. From beneath the windows of the King's apartments in the palace, they called on Bahadur Shah to acknowledge and lead them. He did nothing at this point, apparently treating the sepoys as ordinary petitioners, but others in the palace were quick to join the revolt. During the day, the revolt spread. British officials and dependents, Indian Christians and shop keepers within the city were killed, some by sepoys and others by crowds of rioters.[78]: 71–73

There were three battalion-sized regiments of Bengal Native Infantry stationed in or near the city. Some detachments quickly joined the rebellion, while others held back but also refused to obey orders to take action against the rebels. In the afternoon, a violent explosion in the city was heard for several miles. Fearing that the arsenal, which contained large stocks of arms and ammunition, would fall intact into rebel hands, the nine British Ordnance officers there had opened fire on the sepoys, including the men of their own guard. When resistance appeared hopeless, they blew up the arsenal. Six of the nine officers survived, but the blast killed many in the streets and nearby houses and other buildings.[79] The news of these events finally tipped the sepoys stationed around Delhi into open rebellion. The sepoys were later able to salvage at least some arms from the arsenal, and a magazine two miles (3 km (1.9 mi)) outside Delhi, containing up to 3,000 barrels of gunpowder, was captured without resistance.[citation needed]

Many fugitive British officers and civilians had congregated at the Flagstaff Tower on the ridge north of Delhi, where telegraph operators were sending news of the events to other British stations. When it became clear that the help expected from Meerut was not coming, they made their way in carriages to Karnal. Those who became separated from the main body or who could not reach the Flagstaff Tower also set out for Karnal on foot. Some were helped by villagers on the way; others were killed.[citation needed]

The next day, Bahadur Shah held his first formal court for many years. It was attended by many excited sepoys. The King was alarmed by the turn events had taken, but eventually accepted the sepoys' allegiance and agreed to give his countenance to the rebellion. On 16 May, up to 50 British who had been held prisoner in the palace or had been discovered hiding in the city were killed by some of the King's servants under a peepul tree in a courtyard outside the palace.[80][81]

Supporters and opposition

The news of the events at Meerut and Delhi spread rapidly, provoking uprisings among sepoys and disturbances in many districts. In many cases, it was the behaviour of British military and civilian authorities themselves which precipitated disorder. Learning of the fall of Delhi, many Company administrators hastened to remove themselves, their families and servants to places of safety. At Agra, 160 miles (260 km) from Delhi, no fewer than 6,000 assorted non-combatants converged on the Fort.[82]

The military authorities also reacted in disjointed manner. Some officers trusted their sepoys, but others tried to disarm them to forestall potential uprisings. At Benares and Allahabad, the disarmings were bungled, also leading to local revolts.[83]: 52–53

In 1857, the Bengal Army had 86,000 men, of which 12,000 were British, 16,000 Sikh and 1,500 Gurkha. There were 311,000 native soldiers in India altogether, 40,160 British soldiers (including units of the British Army) and 5,362 officers.[84] Fifty-four of the Bengal Army's 74 regular Native Infantry Regiments mutinied, but some were immediately destroyed or broke up, with their sepoys drifting away to their homes. A number of the remaining 20 regiments were disarmed or disbanded to prevent or forestall mutiny. Only twelve of the original Bengal Native Infantry regiments survived to pass into the new Indian Army.[85] All ten of the Bengal Light Cavalry regiments mutinied.[citation needed]

The Bengal Army also contained 29 irregular cavalry and 42 irregular infantry regiments. Of these, a substantial contingent from the recently annexed state of Awadh mutinied en masse. Another large contingent from Gwalior also mutinied, even though that state's ruler (Jayajirao Scindia) supported the British. The remainder of the irregular units were raised from a wide variety of sources and were less affected by the concerns of mainstream Indian society. Some irregular units actively supported the company: three Gurkha and five of six Sikh infantry units, and the six infantry and six cavalry units of the recently raised Punjab Irregular Force.[86][87]

On 1 April 1858, the number of Indian soldiers in the Bengal army loyal to the company was 80,053.[88][89] However large numbers were hastily raised in the Punjab and North-West Frontier after the outbreak of the Rebellion.[citation needed]

The Bombay army had three mutinies in its 29 regiments, whilst the Madras army had none at all, although elements of one of its 52 regiments refused to volunteer for service in Bengal.[90] Nonetheless, most of southern India remained passive, with only intermittent outbreaks of violence. Many parts of the region were ruled by the Nizams or the Mysore royalty, and were thus not directly under British rule.[citation needed]

Although most of the mutinous sepoys in Delhi were Hindus, a significant proportion of the insurgents were Muslims. The proportion of ghazis grew to be about a quarter of the local fighting force by the end of the siege and included a regiment of suicide ghazis from Gwalior who had vowed never to eat again and to fight until they met certain death at the hands of British troops.[91] However, most Muslims did not share the rebels' dislike of the British administration[92] and their ulema could not agree on whether to declare a jihad.[93] Some Islamic scholars such as Maulana Muhammad Qasim Nanautavi and Maulana Rashid Ahmad Gangohi took up arms against the colonial rule,[94] but many Muslims, among them ulema from both the Sunni and Shia sects, sided with the British.[95] Various Ahl-i-Hadith scholars and colleagues of Nanautavi rejected the jihad.[96] The most influential member of Ahl-i-Hadith ulema in Delhi, Maulana Sayyid Nazir Husain Dehlvi, resisted pressure from the mutineers to call for a jihad and instead declared in favour of British rule, viewing the Muslim-British relationship as a legal contract which could not be broken unless their religious rights were breached.[97]

The Sikhs and Pathans of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province supported the British and helped in the recapture of Delhi.[98] The Sikhs in particular feared reinstatement of Mughal rule in northern India[99] because they had been persecuted by the Mughal dynasty. They also felt disdain towards the Purbiyas or 'Easterners' (Biharis and those from the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh) in the Bengal Army. The Sikhs felt that the bloodiest battles of the First and Second Anglo-Sikh wars (Chillianwala and Ferozeshah), had been won by British troops, while the Hindustani sepoys had refused to meet the Sikhs in battle.[100] These feelings were compounded when Hindustani sepoys were assigned a very visible role as garrison troops in Punjab and awarded profit-making civil posts in the Punjab.[99]

The varied groups in the support and opposing of the uprising is seen as a major cause of its failure.[citation needed]

The revolt

Initial stages

Bahadur Shah Zafar was proclaimed the Emperor of the whole of India. Most contemporary and modern accounts suggest that he was coerced by the sepoys and his courtiers to sign the proclamation against his will.[101] In spite of the significant loss of power that the Mughal dynasty had suffered in the preceding centuries, their name still carried great prestige across northern India.[91] Civilians, nobility and other dignitaries took an oath of allegiance. The emperor issued coins in his name, one of the oldest ways of asserting imperial status. The adhesion of the Mughal emperor, however, turned the Sikhs of the Punjab away from the rebellion, as they did not want to return to Islamic rule, having fought many wars against the Mughal rulers. The province of Bengal was largely quiet throughout the entire period. The British, who had long ceased to take the authority of the Mughal Emperor seriously, were astonished at how the ordinary people responded to Zafar's call for war.[91]

Initially, the Indian rebels were able to push back Company forces, and captured several important towns in Haryana, Bihar, the Central Provinces and the United Provinces. When British troops were reinforced and began to counterattack, the mutineers were especially handicapped by their lack of centralized command and control. Although the rebels produced some natural leaders such as Bakht Khan, whom the Emperor later nominated as commander-in-chief after his son Mirza Mughal proved ineffectual, for the most part they were forced to look for leadership to rajahs and princes. Some of these were to prove dedicated leaders, but others were self-interested or inept.[citation needed]

In the countryside around Meerut, a general Gurjar uprising posed the largest threat to the British. In Parikshitgarh near Meerut, Gurjars declared Choudhari Kadam Singh (Kuddum Singh) their leader, and expelled Company police. Kadam Singh Gurjar led a large force, estimates varying from 2,000 to 10,000.[102] Bulandshahr and Bijnor also came under the control of Gurjars under Walidad Khan and Maho Singh respectively. Contemporary sources report that nearly all the Gurjar villages between Meerut and Delhi participated in the revolt, in some cases with support from Jullundur, and it was not until late July that, with the help of local Jats, and the princely states, the British managed to regain control of the area.[102]

The Imperial Gazetteer of India states that throughout the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Gurjars and Ranghars proved the "most irreconcilable enemies" of the British in the Bulandshahr area.[103]

Mufti Nizamuddin, a renowned scholar of Lahore, issued a Fatwa against the British forces and called upon the local population to support the forces of Rao Tula Ram. Casualties were high at the subsequent engagement at Narnaul (Nasibpur). After the defeat of Rao Tula Ram on 16 November 1857, Mufti Nizamuddin was arrested, and his brother Mufti Yaqinuddin and brother-in-law Abdur Rahman (alias Nabi Baksh) were arrested in Tijara. They were taken to Delhi and hanged.[104]

Siege of Delhi

The British were slow to strike back at first. It took time for troops stationed in Britain to make their way to India by sea, although some regiments moved overland through Persia from the Crimean War, and some regiments already en route for China were diverted to India.[citation needed]

It took time to organise the British troops already in India into field forces, but eventually two columns left Meerut and Simla. They proceeded slowly towards Delhi and fought, killed, and hanged numerous Indians along the way. Two months after the first outbreak of rebellion at Meerut, the two forces met near Karnal. The combined force, including two Gurkha units serving in the Bengal Army under contract from the Kingdom of Nepal, fought the rebels' main army at Badli-ke-Serai and drove them back to Delhi.[citation needed]

The company's army established a base on the Delhi ridge to the north of the city and the Siege of Delhi began. The siege lasted roughly from 1 July to 21 September. However, the encirclement was hardly complete, and for much of the siege the besiegers were outnumbered and it often seemed that it was the Company forces and not Delhi that were under siege, as the rebels could easily receive resources and reinforcements. For several weeks, it seemed likely that disease, exhaustion and continuous sorties by rebels from Delhi would force the besiegers to withdraw, but the outbreaks of rebellion in the Punjab were forestalled or suppressed, allowing the Punjab Movable Column of British, Sikh and Pakhtun soldiers under John Nicholson to reinforce the besiegers on the Ridge on 14 August.[105] On 30 August the rebels offered terms, which were refused.[106]

-

The Jantar Mantar observatory in Delhi in 1858, damaged in the fighting

-

Mortar damage to Kashmiri Gate, Delhi, 1858

-

Hindu Rao's house in Delhi, now a hospital, was extensively damaged in the fighting.Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Indian_Mutiny

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk