A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

日系アメリカ人 Nikkeiamerikajin | |

|---|---|

Japanese Ancestry by state | |

| Total population | |

| 1,550,875 (0.5% of U.S. population including part-Japanese people)[1] (2020) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Hawaii, San Francisco Bay Area, and Greater Los Angeles[2] | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Japanese | |

| Religion | |

| 33% Protestantism 32% Unaffiliated 25% Buddhism 4% Catholicism 4% Shinto[3][4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Japanese people, Ryukyuan Americans |

Japanese Americans (Japanese: 日系アメリカ人) are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 census, they have declined in ranking to constitute the sixth largest Asian American group at around 1,469,637, including those of partial ancestry.[5]

According to the 2010 census, the largest Japanese American communities were found in California with 272,528, Hawaii with 185,502, New York with 37,780, Washington with 35,008, Illinois with 17,542 and Ohio with 16,995.[6] Southern California has the largest Japanese American population in North America and the city of Gardena holds the densest Japanese American population in the 48 contiguous states.[7]

History

Immigration

People from Japan began migrating to the US in significant numbers following the political, cultural, and social changes stemming from the Meiji Restoration in 1868. These early Issei immigrants came primarily from small towns and rural areas in the southern Japanese prefectures of Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Kumamoto, and Fukuoka[8] and most of them settled in either Hawaii or along the West Coast. The Japanese population in the United States grew from 148 in 1880 (mostly students) to 2,039 in 1890 and 24,326 by 1900.[9]

In the earliest years of the 20th century, American officials with no experience in "transliterating...Japanese" often gave Japanese-Americans new names before and during the process of their naturalization.[10]

In 1907, the Gentlemen's Agreement between the governments of Japan and the United States ended immigration of Japanese unskilled workers, but permitted the immigration of businessmen, students and spouses of Japanese immigrants already in the US. Prior to the Gentlemen's Agreement, about seven out of eight ethnic Japanese in the continental United States were men. By 1924, the ratio had changed to approximately four women to every six men.[11] Japanese immigration to the U.S. effectively ended when Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 which banned all but a token few Japanese people. The earlier Naturalization Act of 1790 restricted naturalized United States citizenship to free white persons, which excluded the Issei from citizenship. As a result, the Issei were unable to vote and faced additional restrictions such as the inability to own land under many state laws. Due to these restrictions, Japanese immigration to the United States between 1931 and 1950 only totaled 3,503 which is strikingly low compared to the totals of 46,250 people in 1951–1960, 39,988 in 1961–70, 49,775 in 1971–80, 47,085 in 1981–90, and 67,942 in 1991–2000.[12]

Because no new immigrants from Japan were permitted after 1924, almost all pre-World War II Japanese Americans born after this time were born in the United States. This generation, the Nisei, became a distinct cohort from the Issei generation in terms of age, citizenship, and English-language ability, in addition to the usual generational differences. Institutional and interpersonal racism led many of the Nisei to marry other Nisei, resulting in a third distinct generation of Japanese Americans, the Sansei. Significant Japanese immigration did not occur again until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ended 40 years of bans against immigration from Japan and other countries.

In the last few decades, immigration from Japan has been more like that from Europe. The numbers involve on average 5 to 10 thousand per year, and is similar to the amount of immigration to the US from Germany. This is in stark contrast to the rest of Asia, where better opportunity of life is the primary impetus for immigration.

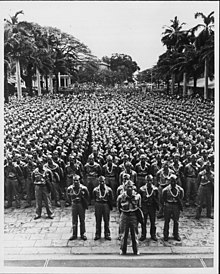

Internment and redress

During World War II, an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals or citizens residing on the West Coast of the United States were forcibly interned in ten different camps across the Western United States. The internment was based on the race or ancestry, rather than the activities of the interned. Families, including children, were interned together.[13] and 5,000 were able to "voluntarily" relocate outside the exclusion zone;[14]

In 1948, the Evacuation Claims Act provided some compensation for property losses, but the act required documentation that many former inmates had lost during their removal and excluded lost opportunities, wages or interest from its calculations. Less than 24,000 filed a claim, and most received only a fraction of the losses they claimed.[15]

Four decades later, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 officially acknowledged the "fundamental violations of the basic civil liberties and constitutional rights" of the internment.[16] Many Japanese Americans consider the term internment camp a euphemism and prefer to refer to the forced relocation of Japanese Americans as imprisonment in concentration camps.[17] Webster's New World Fourth College Edition defines a concentration camp: "A prison camp in which political dissidents, members of minority ethnic groups, etc. are confined."

Cultural profile

Generations

The nomenclature for each of their generations who are citizens or long-term residents of countries other than Japan, used by Japanese Americans and other nationals of Japanese descent are explained here; they are formed by combining one of the Japanese numbers corresponding to the generation with the Japanese word for generation (sei 世). The Japanese American communities have themselves distinguished their members with terms like Issei, Nisei, and Sansei, which describe the first, second, and third generations of immigrants. The fourth generation is called Yonsei (四世), and the fifth is called Gosei (五世). The term Nikkei (日系) encompasses Japanese immigrants in all countries and of all generations.

| Generation | Summary |

|---|---|

| Issei (一世) | The generation of people born in Japan who later immigrated to another country. |

| Nisei (二世) | The generation of people born in North America, Philippines, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside Japan either to at least one Issei or one non-immigrant Japanese parent. |

| Sansei (三世) | The generation of people born in North America, Philippines, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside Japan to at least one Nisei parent. |

| Yonsei (四世) | The generation of people born in North America, Philippines, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside Japan to at least one Sansei parent. |

| Gosei (五世) | The generation of people born in North America, Philippines, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside Japan to at least one Yonsei parent. |

The kanreki (還暦), a pre-modern Japanese rite of passage to old age at 60, is now being celebrated by increasing numbers of Japanese American Nisei. Rituals are enactments of shared meanings, norms, and values; and this traditional Japanese rite of passage highlights a collective response among the Nisei to the conventional dilemmas of growing older.[18]

Languages

Issei and many nisei speak Japanese in addition to English as a second language. In general, later generations of Japanese Americans speak English as their first language, though some do learn Japanese later as a second language. In Hawaii however, where Nikkei are about one-fifth of the whole population, Japanese is a major language, spoken and studied by many of the state's residents across ethnicities.[citation needed] It is taught in private Japanese language schools as early as the second grade. As a courtesy to the large number of Japanese tourists (from Japan), Japanese characters are provided on place signs, public transportation, and civic facilities. The Hawaii media market has a few locally produced Japanese language newspapers and magazines, although these are on the verge of dying out, due to a lack of interest on the part of the local (Hawaii-born) Japanese population. Stores that cater to the tourist industry often have Japanese-speaking personnel. To show their allegiance to the US, many nisei and sansei intentionally avoided learning Japanese. But as many of the later generations find their identities in both Japan and America or American society broadens its definition of cultural identity, studying Japanese is becoming more popular than it once was.[citation needed]

Education

Japanese American culture places great value on education and culture. Across generations, children are often instilled with a strong desire to enter the rigors of higher education. In 1966, sociologist William Petersen (who coined the term "Model Minority") wrote that Japanese Americans "have established this remarkable record, moreover, by their own almost totally unaided effort. Every attempt to hamper their progress resulted only in enhancing their determination to succeed."[19] The 2000 census reported that 40.8% of Japanese Americans held a college degree.[20]

Schools for Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals

A Japanese school opened in Hawaii in 1893 and other Japanese schools for temporary settlers in North America followed.[21] In the years prior to World War II, many second generation Japanese American attended the American school by day and the Japanese school in the evening to keep up their Japanese skill as well as English. Other first generation Japanese American parents were worried that their child might go through the same discrimination when going to school so they gave them the choice to either go back to Japan to be educated, or to stay in America with their parents and study both languages.[22][page needed] Anti-Japanese sentiment during World War I resulted in public efforts to close Japanese-language schools. The 1927 Supreme Court case Farrington v. Tokushige protected the Japanese American community's right to have Japanese language private institutions. During the internment of Japanese Americans in World War II many Japanese schools were closed. After the war many Japanese schools reopened.[23]

There are primary school-junior high school Japanese international schools within the United States. Some are classified as nihonjin gakkō or Japanese international schools operated by Japanese associations,[24] and some are classified as Shiritsu zaigai kyōiku shisetsu (私立在外教育施設) or overseas branches of Japanese private schools.[25] They are: Seigakuin Atlanta International School, Chicago Futabakai Japanese School, Japanese School of Guam, Nishiyamato Academy of California near Los Angeles, Japanese School of New Jersey, and New York Japanese School. A boarding senior high school, Keio Academy of New York, is near New York City. It is a Shiritsu zaigai kyōiku shisetsu.[25]

There are also supplementary Japanese educational institutions (hoshū jugyō kō) that hold Japanese classes on weekends. They are located in several US cities.[26] The supplementary schools target Japanese nationals and second-generation Japanese Americans living in the United States. There are also Japanese heritage schools for third generation and beyond Japanese Americans.[27] Rachel Endo of Hamline University,[28] the author of "Realities, Rewards, and Risks of Heritage-Language Education: Perspectives from Japanese Immigrant Parents in a Midwestern Community," wrote that the heritage schools "generally emphasize learning about Japanese American historical experiences and Japanese culture in more loosely defined terms".[29]

Tennessee Meiji Gakuin High School (shiritsu zaigai kyōiku shisetsu) and International Bilingual School (unapproved by the Japanese Ministry of Education or MEXT) were full-time Japanese schools that were formerly in existence.

Religion

Religious makeup of Japanese-Americans (2012)[30]

Japanese Americans practice a wide range of religions, including Mahayana Buddhism (Jōdo Shinshū, Jōdo-shū, Nichiren, Shingon, and Zen forms), Shinto, and Christianity (usually Protestant or Catholic, being their majority faith as per recent data). In many ways, due to the longstanding nature of Buddhist and Shinto practices in Japanese society, many of the cultural values and traditions commonly associated with Japanese tradition have been strongly influenced by these religious forms.

A large number of the Japanese American community continue to practice Buddhism in some form, and a number of community traditions and festivals continue to center around Buddhist institutions. For example, one of the most popular community festivals is the annual Obon Festival, which occurs in the summer, and provides an opportunity to reconnect with their customs and traditions and to pass these traditions and customs to the young. These kinds of festivals are mostly popular in communities with large populations of Japanese Americans, such as Southern California and Hawaii. A reasonable number of Japanese people both in and out of Japan are secular, as Shinto and Buddhism are most often practiced by rituals such as marriages or funerals, and not through faithful worship, as defines religion for many Americans.

Most Japanese Americans now practice Christianity. Among mainline denominations the Presbyterians have long been active. The First Japanese Presbyterian Church of San Francisco opened in 1885.[31] Los Angeles Holiness Church was founded by six Japanese men and women in 1921.[32] There is also the Japanese Evangelical Missionary Society (JEMS) formed in the 1950s. It operates Asian American Christian Fellowships (AACF) programs on university campuses, especially in California.[33] The Japanese language ministries are fondly known as "Nichigo" in Japanese American Christian communities. The newest trend includes Asian American members who do not have a Japanese heritage.[34]

Celebrations

An important annual festival for Japanese Americans is the Obon Festival, which happens in July or August of each year. Across the country, Japanese Americans gather on fair grounds, churches and large civic parking lots and commemorate the memory of their ancestors and their families through folk dances and food. Carnival booths are usually set up so Japanese American children have the opportunity to play together.

Japanese American celebrations tend to be more sectarian in nature and focus on the community-sharing aspects.

| Date | Name | Region |

|---|---|---|

| January 1 | Shōgatsu New Year's Celebration | Nationwide |

| February | Japanese Heritage Fair | Honolulu, HI |

| February to March | Cherry Blossom Festival | Honolulu, HI |

| March 3 | Hinamatsuri (Girls' Day) | Hawaii |

| March | Honolulu Festival | Honolulu, HI |

| March | Hawaiʻi International Taiko Festival | Honolulu, HI |

| March | International Cherry Blossom Festival | Macon, GA |

| March to April | National Cherry Blossom Festival | Washington, D.C. |

| April | Northern California Cherry Blossom Festival | San Francisco, CA |

| April | Pasadena Cherry Blossom Festival | Pasadena, CA |

| April | Seattle Cherry Blossom Festival | Seattle, WA |

| May 5 | Tango no Sekku (Boys' Day) | Hawaii |

| May | Shinnyo-En Toro-Nagashi (Memorial Day Floating Lantern Ceremony) | Honolulu, HI |

| June | Pan-Pacific Festival Matsuri in Hawaiʻi | Honolulu, HI |

| July 7 | Tanabata (Star Festival) | Nationwide |

| July–August | Obon Festival | Nationwide |

| August | Nihonmachi Street Fair | San Francisco, CA |

| August | Nisei Week | Los Angeles, CA |

Politics

Japanese Americans have shown strong support for Democratic candidates in recent elections. Shortly prior to the 2004 US presidential election, Japanese Americans narrowly favored Democrat John Kerry by a 42% to 38% margin over Republican George W. Bush.[35] In the 2008 US presidential election, the National Asian American Survey found that Japanese Americans favored Democrat Barack Obama by a 62% to 16% margin over Republican John McCain, while 22% were still undecided.[36] In the 2012 presidential election, a majority of Japanese Americans (70%) voted for Barack Obama.[37] In the 2016 presidential election, majority of Japanese Americans (74%) voted for Hillary Clinton.[38] In pre-election surveys for the 2020 presidential election, 61% to 72% of Japanese Americans planned to vote for Joe Biden.[39][40]

Cuisine

Circa 2016, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Japan) calculated that people of Japanese ancestry operated about 10% of the Japanese restaurants in the United States; this was because salaries were relatively high in Japan and few cooks of Japanese cuisine had motivations to move to the United States. This meant Americans and immigrants of other ethnic origins, including Chinese Americans, opened restaurants serving Japanese style cuisine.[41]

Genetics

Risk for inherited diseases

Studies have looked into the risk factors that are more prone to Japanese Americans, specifically in hundreds of family generations of Nisei (The generation of people born in North America, Philippines, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside Japan either to at least one Issei or one non-immigrant Japanese parent) second-generation pro-bands (A person serving as the starting point for the genetic study of a family, used in medicine and psychiatry). The risk factors for genetic diseases in Japanese Americans include coronary heart disease and diabetes. One study, called the Japanese American Community Diabetes Study that started in 1994 and went through 2003, involved the pro-bands taking part to test whether the increased risk of diabetes among Japanese Americans is due to the effects of Japanese Americans having a more westernized lifestyle due to the many differences between the United States of America and Japan. One of the main goals of the study was to create an archive of DNA samples which could be used to identify which diseases are more susceptible in Japanese Americans.

Concerns with these studies of the risks of inherited diseases in Japanese Americans is that information pertaining to the genetic relationship may not be consistent with the reported biological family information given of Nisei second generation pro-bands.[42] Also, research has been put on concerning apolipoprotein E genotypes; this polymorphism has three alleles (*e2, *e3, and *e4) and was determined from research because of its known association with increased cholesterol levels and risk of coronary heart disease in Japanese Americans. Specifically too, the apolipoprotein *e4 allele is linked to Alzheimer's disease as well. Also, there is increased coronary heart disease in Japanese American men with a mutation in the cholesterol ester transfer protein gene despite having increased levels of HDL. By definition, HDL are plasma high density lipoproteins that show a genetic relationship with coronary heart disease (CHD). The cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) helps the transfer of cholesterol esters from lipoproteins to other lipoproteins in the human body. It plays a fundamental role in the reverse transport of cholesterol to the liver, which is why a mutation in this can lead to coronary heart disease.

Studies have shown that the CETP is linked to increased HDL levels. There is a very common pattern of two different cholesterol ester transfer protein gene mutations (D442G, 5.1%; intron 14G:A, 0.5%) found in about 3,469 Japanese American men. This was based on a program called the Honolulu Heart Program. The mutations correlated with decreased CETP levels (-35%) and increased HDL cholesterol levels (+10% for D442G). The relative risk of CHD was 1.43 in men with mutations (P<0.05), and after research found for CHD risk factors, the relative risk went up to 1.55 (P=0.02); after further adjustments for HDL levels, the relative risk went up again to 1.68 (P=0.008). Genetic CETP deficiency is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease, which is due mainly to increased CHD risks in Japanese American men with the D442G mutation and lipoprotein cholesterol levels between 41 and 60 mg/dl.[43] With research and investigations, the possibility of finding "bad genes" denounces the Japanese Americans and will be associated only with Japanese American ancestry, leading to other issues the Japanese Americans had to deal with in the past such as discrimination and prejudice.[44]

Japanese Americans by state

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2013) |

California

In the early 1900s, Japanese Americans established fishing communities on Terminal Island and in San Diego.[45] By 1923, there were two thousand Japanese fishermen sailing out of Los Angeles Harbor.[46] By the 1930s, legislation was passed that attempted to limit Japanese fishermen. Still, areas such as San Francisco's Japantown managed to thrive.

Due to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, historically Japanese areas fell into disrepair or became adopted by other minority groups (in the case of Black and Latino populations in Little Tokyo). Boats owned by Japanese Americans were confiscated by the U.S. Navy.[47] One of the vessels owned by a Japanese American, the Alert, built in 1930,[48] became YP-264 in December 1941,[45] and was finally struck from the Naval Vessel Register in 2014.[49] When Japanese Americans returned from internment, many settled in neighborhoods where they set up their own community centers in order to feel accepted. Today, many have been renamed cultural centers and focus on the sharing of Japanese culture with local community members, especially in the sponsorship of Obon festivals.[50]

The city of Torrance in Greater Los Angeles has headquarters of Japanese automakers and offices of other Japanese companies. Because of the abundance of Japanese restaurants and other cultural offerings are in the city, and Willy Blackmore of L.A. Weekly wrote that Torrance was "essentially Japan's 48th prefecture".[51]

Colorado

From the early 20th century, Japanese immigrants to the state often came from rural parts of Japan and the "prosperous Aichi Prefecture".[10]

There were roughly 11,000 people of Japanese heritage in Colorado as of 2005. The history up until 2005 was covered in the book Colorado's Japanese Americans: From 1886 to the Present by award-winning author and journalist Bill Hosokawa. One of the first documented was engineer Tadaatsu Matsudaira who moved there for health reasons in 1886.[52] The Granada Relocation Center which incarcerated more than 10,000 Japanese Americans from 1942 to 1945, was designated as part of the National Park System on March 18, 2022, and is located in southeastern Colorado.[53] Colorado is also home to several rural farms, many multi-generational dating back to the end of World War II, owned by people of Japanese ancestry.[54]

Connecticut

Two supplementary Japanese language schools are located in Connecticut, each educating the local Japanese population. The Japanese School of New York is located in Greenwich, Connecticut in Greater New York City; it had formerly been located in New York City. There is also the Japanese Language School of Greater Hartford, located in Hartford, Connecticut.

Georgia

The Seigakuin Atlanta International School is located in Peachtree Corners in Greater Atlanta.

Hawaii

Illinois

As of 2011 there is a Japanese community in Arlington Heights, near Chicago. Jay Shimotake, the president of the Mid America Japanese Club, an organization located in Arlington Heights, said "Arlington Heights is a very convenient location, and Japanese people in the business environment know it's a nice location surrounding O'Hare airport."[55] The Chicago Futabakai Japanese School is located in Arlington Heights. The Mitsuwa Marketplace, a shopping center owned by Japanese, opened around 1981. Many Japanese companies have their US headquarters in nearby Hoffman Estates and Schaumburg.[55]

Massachusetts

There is a Japanese School of Language in Medford.[56] Another, the Amherst Japanese Language School, is in South Hadley, in the 5-college area of the western part of the state.[57] Most Japanese Americans in the state live in Greater Boston, with a high concentration in the town of Brookline.

Porter Square, Cambridge has a Japanese-cultural district and shopping plaza.

Michigan

As of April 2013, the largest Japanese national population in Michigan is in Novi, with 2,666 Japanese residents, and the next largest populations are respectively in Ann Arbor, West Bloomfield Township, Farmington Hills, and Battle Creek. The state has 481 Japanese employment facilities providing 35,554 local jobs. 391 of them are in Southeast Michigan, providing 20,816 jobs, and the 90 in other regions in the state provide 14,738 jobs. The Japanese Direct Investment Survey of the Consulate-General of Japan, Detroit stated that over 2,208 more Japanese residents were employed in the State of Michigan as of October 1, 2012, than had been in 2011.[58]

Missouriedit

Many Japanese Americans in Missouri live in the St. Louis area and are the descendants of those who were previously interned in camps such as one in Arkansas.[59]

New Jerseyedit

As of March 2011 about 2,500 Japanese Americans combined live in Edgewater and Fort Lee; this is the largest concentration of Japanese Americans in the state.[60] The New Jersey Japanese School is located in Oakland. Paramus Catholic High School hosts a weekend Japanese school, and Englewood Cliffs has a Japanese school. Other smaller Japanese American populations are also located in the remainder of Bergen County and other parts of the state. Mitsuwa Marketplace has a location in Edgewater that also houses a mini shopping complex.[61]

New Yorkedit

Oklahomaedit

The 1990 census recorded 2,385 Japanese Americans in Oklahoma.[62] Historically, they lived in Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Bartlesville, and Ponca City and none were interned during World War II.[62]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Japanese_American

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk