A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

In biology, a kingdom is the second highest taxonomic rank, just below domain. Kingdoms are divided into smaller groups called phyla (singular phylum).

Traditionally, some textbooks from the United States and Canada used a system of six kingdoms (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, Archaea/Archaebacteria, and Bacteria or Eubacteria), while textbooks in other parts of the world, such as the United Kingdom, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Greece, Brazil, Spain use five kingdoms only (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista and Monera).

Some recent classifications based on modern cladistics have explicitly abandoned the term kingdom, noting that some traditional kingdoms are not monophyletic, meaning that they do not consist of all the descendants of a common ancestor. The terms flora (for plants), fauna (for animals), and, in the 21st century, funga (for fungi) are also used for life present in a particular region or time.[1][2]

Definition and associated terms

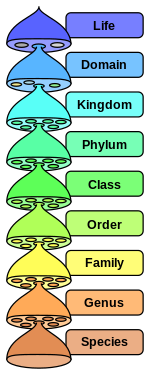

When Carl Linnaeus introduced the rank-based system of nomenclature into biology in 1735, the highest rank was given the name "kingdom" and was followed by four other main or principal ranks: class, order, genus and species.[3] Later two further main ranks were introduced, making the sequence kingdom, phylum or division, class, order, family, genus and species.[4] In 1990, the rank of domain was introduced above kingdom.[5]

Prefixes can be added so subkingdom (subregnum) and infrakingdom (also known as infraregnum) are the two ranks immediately below kingdom. Superkingdom may be considered as an equivalent of domain or empire or as an independent rank between kingdom and domain or subdomain. In some classification systems the additional rank branch (Latin: ramus) can be inserted between subkingdom and infrakingdom, e.g., Protostomia and Deuterostomia in the classification of Cavalier-Smith.[6]

History

Two kingdoms of life

The classification of living things into animals and plants is an ancient one. Aristotle (384–322 BC) classified animal species in his History of Animals, while his pupil Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BC) wrote a parallel work, the Historia Plantarum, on plants.[7]

Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) laid the foundations for modern biological nomenclature, now regulated by the Nomenclature Codes, in 1735. He distinguished two kingdoms of living things: Regnum Animale ('animal kingdom') and Regnum Vegetabile ('vegetable kingdom', for plants). Linnaeus also included minerals in his classification system, placing them in a third kingdom, Regnum Lapideum.

| ||||||||||||||||

Three kingdoms of life

In 1674, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, often called the "father of microscopy", sent the Royal Society of London a copy of his first observations of microscopic single-celled organisms. Until then, the existence of such microscopic organisms was entirely unknown. Despite this, Linnaeus did not include any microscopic creatures in his original taxonomy.

At first, microscopic organisms were classified within the animal and plant kingdoms. However, by the mid–19th century, it had become clear to many that "the existing dichotomy of the plant and animal kingdoms rapidly blurred at its boundaries and outmoded".[8]

In 1860 John Hogg proposed the Protoctista, a third kingdom of life composed of "all the lower creatures, or the primary organic beings"; he retained Regnum Lapideum as a fourth kingdom of minerals.[8] In 1866, Ernst Haeckel also proposed a third kingdom of life, the Protista, for "neutral organisms" or "the kingdom of primitive forms", which were neither animal nor plant; he did not include the Regnum Lapideum in his scheme.[8] Haeckel revised the content of this kingdom a number of times before settling on a division based on whether organisms were unicellular (Protista) or multicellular (animals and plants).[8]

Four kingdoms

The development of microscopy revealed important distinctions between those organisms whose cells do not have a distinct nucleus (prokaryotes) and organisms whose cells do have a distinct nucleus (eukaryotes). In 1937 Édouard Chatton introduced the terms "prokaryote" and "eukaryote" to differentiate these organisms.[9]

In 1938, Herbert F. Copeland proposed a four-kingdom classification by creating the novel Kingdom Monera of prokaryotic organisms; as a revised phylum Monera of the Protista, it included organisms now classified as Bacteria and Archaea. Ernst Haeckel, in his 1904 book The Wonders of Life, had placed the blue-green algae (or Phycochromacea) in Monera; this would gradually gain acceptance, and the blue-green algae would become classified as bacteria in the phylum Cyanobacteria.[8][9]

In the 1960s, Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel promoted and popularized Édouard Chatton's earlier work, particularly in their paper of 1962, "The Concept of a Bacterium"; this created, for the first time, a rank above kingdom—a superkingdom or empire—with the two-empire system of prokaryotes and eukaryotes.[9] The two-empire system would later be expanded to the three-domain system of Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota.[10]

| Life | |

Five kingdoms

The differences between fungi and other organisms regarded as plants had long been recognised by some; Haeckel had moved the fungi out of Plantae into Protista after his original classification,[8] but was largely ignored in this separation by scientists of his time. Robert Whittaker recognized an additional kingdom for the Fungi.[11] The resulting five-kingdom system, proposed in 1969 by Whittaker, has become a popular standard and with some refinement is still used in many works and forms the basis for new multi-kingdom systems. It is based mainly upon differences in nutrition; his Plantae were mostly multicellular autotrophs, his Animalia multicellular heterotrophs, and his Fungi multicellular saprotrophs.

The remaining two kingdoms, Protista and Monera, included unicellular and simple cellular colonies.[11] The five kingdom system may be combined with the two empire system. In the Whittaker system, Plantae included some algae. In other systems, such as Lynn Margulis's system of five kingdoms, the plants included just the land plants (Embryophyta), and Protoctista has a broader definition.[12][page needed]

Following publication of Whittaker's system, the five-kingdom model began to be commonly used in high school biology textbooks.[13] But despite the development from two kingdoms to five among most scientists, some authors as late as 1975 continued to employ a traditional two-kingdom system of animals and plants, dividing the plant kingdom into subkingdoms Prokaryota (bacteria and cyanobacteria), Mycota (fungi and supposed relatives), and Chlorota (algae and land plants).[14]

| Life | |

|

Kingdom Monera

|

Kingdom Protista

|

Kingdom Plantae

|

Kingdom Fungi

|

Kingdom Animalia

|

Six kingdoms

In 1977, Carl Woese and colleagues proposed the fundamental subdivision of the prokaryotes into the Eubacteria (later called the Bacteria) and Archaebacteria (later called the Archaea), based on ribosomal RNA structure;[15] this would later lead to the proposal of three "domains" of life, of Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota.[5] Combined with the five-kingdom model, this created a six-kingdom model, where the kingdom Monera is replaced by the kingdoms Bacteria and Archaea.[16] This six-kingdom model is commonly used in recent US high school biology textbooks, but has received criticism for compromising the current scientific consensus.[13] But the division of prokaryotes into two kingdoms remains in use with the recent seven kingdoms scheme of Thomas Cavalier-Smith, although it primarily differs in that Protista is replaced by Protozoa and Chromista.[17]

| Life |

| |||||||||||||||

Eight kingdoms

Thomas Cavalier-Smith supported the consensus at that time, that the difference between Eubacteria and Archaebacteria was so great (particularly considering the genetic distance of ribosomal genes) that the prokaryotes needed to be separated into two different kingdoms. He then divided Eubacteria into two subkingdoms: Negibacteria (Gram-negative bacteria) and Posibacteria (Gram-positive bacteria). Technological advances in electron microscopy allowed the separation of the Chromista from the Plantae kingdom. Indeed, the chloroplast of the chromists is located in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum instead of in the cytosol. Moreover, only chromists contain chlorophyll c. Since then, many non-photosynthetic phyla of protists, thought to have secondarily lost their chloroplasts, were integrated into the kingdom Chromista.

Finally, some protists lacking mitochondria were discovered.[18] As mitochondria were known to be the result of the endosymbiosis of a proteobacterium, it was thought that these amitochondriate eukaryotes were primitively so, marking an important step in eukaryogenesis. As a result, these amitochondriate protists were separated from the protist kingdom, giving rise to the, at the same time, superkingdom and kingdom Archezoa. This superkingdom was opposed to the Metakaryota superkingdom, grouping together the five other eukaryotic kingdoms (Animalia, Protozoa, Fungi, Plantae and Chromista). This was known as the Archezoa hypothesis, which has since been abandoned;[19] later schemes did not include the Archezoa–Metakaryota divide.[6][17]