A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Russia |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Topics |

| Symbols |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

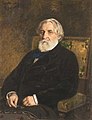

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia, its émigrés, and to Russian-language literature.[1] The roots of Russian literature can be traced to the Early Middle Ages when Old Church Slavonic was introduced as a liturgical language and became used as a literary language. The native Russian vernacular remained the use within oral literature as well as written for decrees, laws, massages, chronicles, military tales, and so on. By the Age of Enlightenment, literature had grown in importance, and from the early 1830s, Russian literature underwent an astounding "Golden Age" in poetry, prose and drama. The Romantic movement contributed to a flowering of literary talent: poet Vasily Zhukovsky and later his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore. Mikhail Lermontov was one of the most important poets and novelists. Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev wrote masterful short stories and novels. Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy became internationally renowned. Other important figures were Ivan Goncharov, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin and Nikolai Leskov. In the second half of the century Anton Chekhov excelled in short stories and became a leading dramatist. The end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century is sometimes called the Silver Age of Russian poetry. The poets most often associated with the "Silver Age" are Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, Alexander Blok, Anna Akhmatova, Nikolay Gumilyov, Sergei Yesenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Marina Tsvetaeva. This era produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as Aleksandr Kuprin and Nobel Prize winners Ivan Bunin, Leonid Andreyev, Fyodor Sologub, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Alexander Belyaev, Andrei Bely and Maxim Gorky.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, literature split into Soviet and white émigré parts. While the Soviet Union assured universal literacy and a highly developed book printing industry, it also established ideological censorship. In the 1930s Socialist realism became the predominant trend in Russia. Its leading figures were Nikolay Ostrovsky, Alexander Fadeyev and other writers, who laid the foundations of this style. Ostrovsky's novel How the Steel Was Tempered has been among the most popular works of Russian Socrealist literature. Some writers, such as Mikhail Bulgakov, Andrei Platonov and Daniil Kharms were criticized and wrote with little or no hope of being published. Various émigré writers, such as poets Vladislav Khodasevich, Georgy Ivanov and Vyacheslav Ivanov; novelists such as Ivan Shmelyov, Gaito Gazdanov, Vladimir Nabokov and Bunin, continued to write in exile. Some writers dared to oppose Soviet ideology, like Nobel Prize-winning novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Varlam Shalamov, who wrote about life in the gulag camps. The Khrushchev Thaw brought some fresh wind to literature and poetry became a mass cultural phenomenon. This "thaw" did not last long; in the 1970s, some of the most prominent authors were banned from publishing and prosecuted for their anti-Soviet sentiments.

The post-Soviet end of the 20th century was a difficult period for Russian literature, with few distinct voices. Among the most discussed authors of this period were novelists Victor Pelevin and Vladimir Sorokin, and the poet Dmitri Prigov. In the 21st century, a new generation of Russian authors appeared, differing greatly from the postmodernist Russian prose of the late 20th century, which led critics to speak about "new realism".

Russian authors have significantly contributed to numerous literary genres. Major contributors to Russian literature, as well as English for example, are authors of different ethnic origins, including bilingual writers, such as Kyrgyz Chinghiz Aitmatov.[1] Russia has five Nobel Prize in literature laureates. As of 2011, Russia was the fourth largest book producer in the world in terms of published titles.[2] A popular folk saying claims Russians are "the world's most reading nation".[3][4] As the American scholar Gary Saul Morson notes, "No country has ever valued literature more than Russia."[5]

Medieval and early modern era

Scholars typically use the term Old Russian, in addition to the terms medieval Russian literature and early modern Russian literature,[6] or pre-Petrian literature,[7] to refer to Russian literature until the reforms of Peter the Great, tying literary development to historical periodization. The term is generally used to refer to all forms of literary activity in what is often called Old Russia from the 11th to 17th centuries.[8][9]

Literary works from this period were often written in the Russian recension of Church Slavonic with varying amounts of the Russian or more broadly East Slavic vernacular.[10][11] At the same time, the native Old Russian vernacular was not only language of oral literature, such as epic poems (bylina) or folksongs,[12] but it was also perfectly legitimate as written for practical purposes, such as decrees, laws (the Russkaya Pravda, the 11th–12th century, and other codes), letters (for example, the unique pre-paper birch bark manuscripts, the 11th–15th centuries, in Old Novgorod dialect), ambassadorial massages,[10] "in chronicles or military tales whose language is fundamentally the Russian vernacular."[10]

Old Russian "bookish" literature traces its beginnings to the introduction of Old Church Slavonic in Kievan Rus' as a liturgical language in the late 10th century following Christianization.[13][14] The East Slavs soon developed their own literature, and the oldest dated manuscript of Old Russian literature that has survived to this day is the Ostromir Gospels written in 1056–1057, which belongs to the set of liturgical texts that were translated from other languages.[15][16]

The main type of Old Russian historical literature were chronicles, most of them anonymous.[17] The oldest one is the Primary Chronicle or Tale of Nestor the Chronicler (c. 1115).[18] The oldest surviving manuscripts include the Laurentian Codex of 1377 and the Hypatian Codex dating to the 1420s.[19] Anonymous works include The Tale of Igor's Campaign and Praying of Daniel the Immured.[20] Hagiographies (Russian: жития святых, romanized: zhitiya svyatykh, lit. 'lives of the saints') formed a popular literary genre in Old Russian literature. The first notable hagiographer was Nestor the Chronicler, who wrote about the lives of Boris and Gleb, the first saints of Kievan Rus', and the abbot Theodosius.[21] The Life of Alexander Nevsky is a well-known example, which combines political realism and hagiographical ideals, and concentrates on the key events of Alexander Nevsky's political career.[22] The earliest account of a pilgrimage is The Pilgrimage of the Abbot Daniel, which records the journey of Daniel the Traveller to the Holy Land.[23] Complex epic works such as The Tale of the Destruction of Ryazan recall the havoc caused by the Mongol invasions.[24] Other notable Russian literary works include Zadonschina, Physiologist, Synopsis and A Journey Beyond the Three Seas.[25] Medieval Russian literature had an overwhelmingly religious character and used an adapted form of the Church Slavonic language with many South Slavic elements.[26]

In the 16th century, reflecting the political centralization and unification of the country under the tsar, chronicles were updated and codified, the Russian Orthodox Church began issuing its decrees in the Stoglav, and a large compilation called the Great Menaion Reader collected both the more modern polemical texts and the hagiographical and patristic legacy of Old Russia.[27] The Book of Royal Degrees codified the cult of the tsar, the Domostroy laid down the rules for family life, and other texts such as the History of Kazan were used to justify the actions of the tsar.[28] The Tale of Peter and Fevronia were among the original tales of this period, and Russian tsar Ivan IV wrote some of most original works of 16th-century Russian literature.[28] The Time of Troubles marked a turning point in Old Russian literature as both the church and state lost control over the written word, which are reflected in the texts of writers such as Avraamy Palitsyn who developed a literary technique for representing complex characters.[29] In the 17th century, when bookmen from the Kiev Academy arrived in Moscow, they brought with them a culture heavily influenced by the educational system of the Polish Jesuits.[30] Simeon of Polotsk created a new style which fused elements of ancient and contemporary Western European literature with traditional Russian rhetoric and the imperial ideology, which marked a key step in the Westernization of Russian literature.[31] Syllabic poetry was also brought to Russia, and the work of Simeon of Polotsk was continued by Sylvester Medvedev and Karion Istomin.[31]

The Life of the Archpriest Avvakum—an outstanding novelty autobiography written by the one of leaders of the 17th-century religious dissidents Old Believers Avvakum—is considered masterpiece of pre-Petrian literature, which blends high Old Church Slavonic with low Russian vernacular and profanity without following literary canons.[32]

18th century

After taking the throne at the end of the 17th century, Peter the Great's influence on the Russian culture would extend far into the 18th century. Peter's reign during the beginning of the 18th century initiated a series of modernizing changes in Russian literature. The reforms he implemented encouraged Russian artists and scientists to make innovations in their crafts and fields with the intention of creating an economy and culture comparable. Peter's example set a precedent for the remainder of the 18th century as Russian writers began to form clear ideas about the proper use and progression of the Russian language. Through their debates regarding versification of the Russian language and tone of Russian literature, the writers in the first half of the 18th century were able to lay foundation for the more poignant, topical work of the late 18th century.[33]

Satirist Antiokh Dmitrievich Kantemir, 1708–1744, was one of the earliest Russian writers not only to praise the ideals of Peter I's reforms but the ideals of the growing Enlightenment movement in Europe. Kantemir's works regularly expressed his admiration for Peter, most notably in his epic dedicated to the emperor entitled Petrida. More often, however, Kantemir indirectly praised Peter's influence through his satiric criticism of Russia's "superficiality and obscurantism", which he saw as manifestations of the backwardness Peter attempted to correct through his reforms.[34] Kantemir honored this tradition of reform not only through his support for Peter, but by initiating a decade-long debate on the proper syllabic versification using the Russian language.

Vasily Kirillovich Trediakovsky, a poet, playwright, essayist, translator and contemporary to Antiokh Kantemir, also found himself deeply entrenched in Enlightenment conventions in his work with the Russian Academy of Sciences and his groundbreaking translations of French and classical works to the Russian language. A turning point in the course of Russian literature, his translation of Paul Tallemant's work Voyage to the Isle of Love, was the first to use the Russian vernacular as opposed the formal and outdated Church-Slavonic.[35] This introduction set a precedent for secular works to be composed in the vernacular, while sacred texts would remain in Church-Slavonic. However, his work was often incredibly theoretical and scholarly, focused on promoting the versification of the language with which he spoke.

While Trediakovsky's approach to writing is often described as highly erudite, the young writer and scholarly rival to Trediakovsky, Alexander Petrovich Sumarokov, 1717–1777, was dedicated to the styles of French classicism.[33] Sumarokov's interest in the form of the 17th-century French literature mirrored his devotion to the westernizing spirit of Peter the Great's age. Although he often disagreed with Trediakovsky, Sumarokov also advocated the use of simple, natural language in order to diversify the audience and make more efficient use of the Russian language. Like his colleagues and counterparts, Sumarokov extolled the legacy of Peter I, writing in his manifesto Epistle on Poetry, "The great Peter hurls his thunder from the Baltic shores, the Russian sword glitters in all corners of the universe".[36] Peter the Great's policies of westernization and displays of military prowess naturally attracted Sumarokov and his contemporaries.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov, in particular, expressed his gratitude for and dedication to Peter's legacy in his unfinished Peter the Great, Lomonosov's works often focused on themes of the awe-inspiring, grandeur nature, and was therefore drawn to Peter because of the magnitude of his military, architectural and cultural feats. In contrast to Sumarokov's devotion to simplicity, Lomonosov favored a belief in a hierarchy of literary styles divided into high, middle and low. This style facilitated Lomonosov's grandiose, high minded writing and use of both vernacular and Church-Slavonic.[37][33]

The influence of Peter I and debates over the function and form of literature as it related to the Russian language in the first half of the 18th century set a stylistic precedent for the writers during the reign of Catherine the Great in the second half of the century. However, the themes and scopes of the works these writers produced were often more poignant, political and controversial. Ippolit Bogdanovich's narrative poem Dushenka (1778) is rare sample of the Rococo style, erotic light poetry in Russia.[38] Alexander Nikolayevich Radishchev, for example, shocked the Russian public with his depictions of the socio-economic condition of the serfs. Empress Catherine II condemned this portrayal, forcing Radishchev into exile in Siberia.[39]

Others, however, picked topics less offensive to the autocrat. the historian and writer Nikolay Karamzin, 1766–1826, the key figure of literary sentimentalism in Russia,[7][40] for example, is known for his advocacy of Russian writers adopting traits in the poetry and prose like a heightened sense of emotion and physical vanity, considered to be feminine at the time as well as supporting the cause of female Russian writers.[41][42][43] Karamzin's call for male writers to write with femininity was not in accordance with the Enlightenment ideals of reason and theory, considered masculine attributes. His works were thus not universally well received; however, they did reflect in some areas of society a growing respect for, or at least ambivalence toward, a female ruler in Catherine the Great. This concept heralded an era of regarding female characteristics in writing as an abstract concept linked with attributes of frivolity, vanity and pathos.

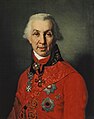

Some writers, on the other hand, were more direct in their praise for Catherine II. Gavrila Romanovich Derzhavin, famous for his odes, often dedicated his poems to Empress Catherine II. In contrast to most of his contemporaries, Derzhavin was highly devoted to his state; he served in the military, before rising to various roles in Catherine II's government, including secretary to the Empress and Minister of Justice. Unlike those who took after the grand style of Mikhail Lomonosov and Alexander Sumarokov, Derzhavin was concerned with the minute details of his subjects.

Denis Fonvizin, an author primarily of comedy, approached the subject of the Russian nobility with an angle of critique. Fonvizin felt the nobility should be held to the standards they were under the reign of Peter the Great, during which the quality of devotion to the state was rewarded. His works criticized the current system for rewarding the nobility without holding them responsible for the duties they once performed. Using satire and comedy, Fonvizin supported a system of nobility in which the elite were rewarded based upon personal merit rather than the hierarchal favoritism that was rampant during Catherine the Great's reign.[44]

Golden Age

I lay, and heard the voice of God:

"Arise, oh prophet, watch and hearken,

And with my Will thy soul engird,

Through lands that dim and seas that darken,

Burn thou men's hearts with this, my Word."

—Alexander Pushkin, The Prophet (1826), translated by

Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky[45]

The 19th century is traditionally referred to as the "Golden Era" of Russian literature.[46] Romantic literature permitted a flowering of especially poetic talent: the names of Vasily Zhukovsky and later that of his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore.[47] Pushkin is credited with both crystallizing the literary Russian language and introducing a new level of artistry to Russian literature. His best-known work is a novel in verse, Eugene Onegin (1833).[48] For early Romanticism is also important the figures of poet Konstantin Batyushkov and "Russian Hoffmann", novelist and musical critic Vladimir Odoyevsky. An entire new generation of Romantic poets including Mikhail Lermontov (wrote narrative poem Demon, 1829–39, discribed the love of a Byronic Demon for a mortal woman; also known for the first Russian psychological novel A Hero of Our Time, 1841), Yevgeny Baratynsky, Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, Fyodor Tyutchev and Afanasy Fet followed in Pushkin's steps.[47] Fyodor Tyutchev is best known for the following verse:

Who would grasp Russia with the mind?

For her no yardstick was created:

Her soul is of a special kind,

By faith alone appreciated.— Fyodor Tyutchev, Who would grasp Russia with the mind? (1866), translated by John Dewey[49]

Prose was flourishing as well. The first great Russian novel was Dead Souls (1842) by Nikolai Gogol. The realistic Natural School of fiction is said to have begun with Ivan Goncharov, mainly remembered for his novel Oblomov (1859), and Ivan Turgenev.[50] Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Leo Tolstoy soon became internationally renowned to the point that many scholars such as F. R. Leavis have described one or the other as the greatest novelist ever. Tolstoy's Christian anarchism can be represented by following quote:

Plants, birds, insects and children were equally joyful. Only men—grown-up men—continued cheating and tormenting themselves and each other. People saw nothing holy in this spring morning, in this beauty of God's world—a gift to all living creatures—inclining to peace, good-will and love, but worshiped their own inventions for imposing their will on each other.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is known for his grotesque satire, and the satirical chronicle The History of a Town (1870) and the family saga The Golovlyov Family (1880) are considered his masterpieces. Nikolai Leskov is best remembered for his shorter fiction and for his unique skaz techniques. Late in the century Anton Chekhov emerged as a master of the short story as well as a leading international dramatist.

Other important 19th-century developments included the father of Russian social realism poetry school, known for the sharp epic poem Who Can Be Happy and Free in Russia? Nikolay Nekrasov; the fabulist Ivan Krylov; the precursor of Naturalism Aleksey Pisemsky; non-fiction writers such as the critic Vissarion Belinsky and the political reformer Alexander Herzen; playwrights such as Aleksandr Griboyedov, Aleksandr Ostrovsky, Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin and the satirist Kozma Prutkov (a collective pen name).

Silver Age

Night, street and streetlight, drug store,

The purposeless, half-dim, drab light.

For all the use live on a quarter century —

Nothing will change. There's no way out.

You'll die — and start all over, live twice,

Everything repeats itself, just as it was:

Night, the canal's rippled icy surface,

The drug store, the street, and streetlight.

—Alexander Blok, Night, street and

streetlight, drug store... (1912),

translated by Alex Cigale

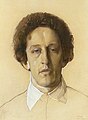

The 1890s and the beginning of the 20th century ranks as the Silver Age of Russian poetry.[7] Well-known poets of the period include: Alexander Blok, Sergei Yesenin, Valery Bryusov, Konstantin Balmont, Mikhail Kuzmin, Igor Severyanin, Sasha Chorny, Nikolay Gumilyov, Maximilian Voloshin, Innokenty Annensky, Zinaida Gippius. The poets most often associated with the "Silver Age" are Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, and Boris Pasternak.[52]

The Russian symbolism was the first Silver Age development in the 1890s. It arose enough separately from West European symbolism, emphasizing mysticism of Sophiology and defamiliarization. Its most significant figures included philosopher and poet Vladimir Solovyov (1953–1900), poets and writers Valery Bryusov (1973–1924), Fyodor Sologub (1963–1927), Vyacheslav Ivanov (1966–1949), Konstantin Balmont (1967–1942), and figures of the new wave generation Alexander Blok (1980–1921) with Andrei Bely (1980–1934).[53][7][54]

While the Silver Age is considered to be the development of the 19th-century Russian Golden Age literature tradition, some modernist and avant-garde poets tried to overturn it. Most prominent their movements: the Cubo-Futurism with practice of zaum, the experimental visual and sound poetry (David Burliuk, Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, Nikolai Aseyev, Vladimir Mayakovsky);[55] the Ego-Futurism based on a personality cult (Igor Severyanin and Vasilisk Gnedov);[56] and the Acmeist poetry, a Russian modernist school, which emerged ca. 1911 and to symbols preferred direct expression through exact images (Anna Akhmatova, Nikolay Gumilev, Georgiy Ivanov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Osip Mandelstam).[57][58]

Though the Silver Age is famous mostly for its poetry, it produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as naturalist Aleksandr Kuprin, Nobel Prize winner, realist Ivan Bunin, pioneer of Russian expressionism Leonid Andreyev, symbolists Fedor Sologub, Aleksey Remizov, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Andrei Bely, Alexander Belyaev, and Yevgeny Zamyatin, though most of them wrote poetry as well as prose.[52]

In 1915/16, the school of Russian Formalism, wary of the futurists and highly influential for the global theory of literary criticism and poetics, appeared; its programmatic article The Resurrection of the Word by the scholar and writer Viktor Shklovsky (1893–1984) was published in 1914, and the peak of activity occurred in the post-revolutionary '20s.[59][60]

Soviet era

Early post-Revolutionary era

The first years of the Soviet regime after the October Revolution of 1917, featured a proliferation of Russian avant-garde literary groups, and proletarian literature together with New Peasant Poets receive official support. The Imaginists were post-Revolution poetic movement, similar to English-language Imagists, that created poetry based on sequences of arresting and uncommon images. The major figures include Sergei Yesenin, Anatoly Marienhof, and Rurik Ivnev.[61] Another important movement was the Oberiu (1927–1930s), which included the most famous Russian absurdist Daniil Kharms (1905–1942), Konstantin Vaginov (1899–1934), Alexander Vvedensky (1904–1941) and Nikolay Zabolotsky (1903–1958).[62][63] Other famous authors experimenting with language included the novelists Yuri Olesha (1899–1960), Andrei Platonov (1899–1951) and Boris Pilnyak (1894–1938) and the short-story writers Isaak Babel (1894–1940) and Mikhail Zoshchenko (1894–1958).[62] The OPOJAZ group of literary critics, a part of Russian formalism school, was founded in 1916 in close connection with Russian Futurism. Two of its members also produced influential literary works, namely Viktor Shklovsky, whose numerous books (A Sentimental Journey and Zoo, or Letters Not About Love, both 1923) defy genre in that they present a novel mix of narration, autobiography, and aesthetic as well as social commentary, and Yury Tynyanov (1893–1943), who used his knowledge of Russia's literary history to produce a set of historical novels mainly set in the Pushkin era (e.g., Lieutenant Kijé, Pushkin in three parts, 1935–43, and others).[59]

Following the establishment of Bolshevik rule, Mayakovsky worked on interpreting the facts of the new reality. His works, such as "Ode to the Revolution" and "Left March" (both 1918), brought innovations to poetry. In "Left March", Mayakovsky calls for a struggle against the enemies of the Russian Revolution. The poem 150 000 000 (1921) discusses the leading role played by the masses in the revolution. In the poem Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1924), Mayakovsky looks at the life and work at the leader of Russia's revolution and depicts them against a broad historical background. In the poem All Right! (1927), Mayakovsky writes about socialist society as the "springtime of humanity". Mayakovsky was instrumental in producing a new type of poetry in which politics played a major part.[64]

Émigré writers

I am an American writer, born in Russia, educated in England, where I studied French literature before moving to Germany for fifteen years. ... My head speaks English, my heart speaks Russian, and my ear speaks French.

Vladimir Nabokov, from the interview

Usually, Russian émigré literature is understood as the works of the white émigré, namely the first post-Revolutionary wave, although in the broad sense of the word, it also includes Soviet dissidents of the late years through the 1980s.[65] Meanwhile, émigré writers, such as poets Georgy Ivanov, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Vladislav Khodasevich, and members of the 1920s–50s Paris Note (French: Note parisienne) Russian poetry movement (Georgy Adamovich, Igor Chinnov, George Ivask, Anatoly Shteiger, Lidia Tcherminskaia); novelists such as M. Ageyev, Mark Aldanov, Gaito Gazdanov, Pyotr Krasnov, Aleksandr Kuprin, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Aleksey Remizov, Ivan Shmelyov, George Grebenstchikoff, Vladimir Nabokov, and English-speaking Ayn Rand; and short-story Nobel Prize-winning writer Ivan Bunin, continued to write in exile.[65] During his emigration Bunin wrote his most significant works, such as his only autobiographical novel The Life of Arseniev (1927–1939) and short story cycle Dark Avenues (1937–1944). An example of long prose form is Grebenstchikoff's epic novel The Churaevs in six volumes (1922–1937) in which he described life of the Siberians.[62] While Bunin, Shmelyov and Grebenstchikoff wrote about the pre-revolutionary Russia, life of the émigrés was depicted in Nabokov's Mary (1926) and The Gift (1938), Gazdanov's An Evening with Claire (1929) and The Specter of Alexander Wolf (1948) and Georgy Ivanov's novel Disintegration of the Atom (1938).[66][65]

-

Lidia Tcherminskaia

Stalinist era

In the 1930s, Socialist realism became the predominant official trend in the Soviet Union. Writers like those of the Serapion Brothers group (1921–), who insisted on the right of an author to write independently of political ideology, were forced by authorities to reject their views and accept socialist realist principles. Some 1930s writers, such as Osip Mandelstam, Daniil Kharms, leader of Oberiu, Leonid Dobychin l, Mikhail Bulgakov, author of The White Guard (1923) and The Master and Margarita (1928–1940), and Andrei Platonov, author of novels Chevengur (1928) and The Foundation Pit (1930) were attacked by the official critics as "formalists," "naturalists" and ideological enemies and wrote with little or no hope of being published. Such remarkable writers as Isaac Babel and Boris Pilnyak, who continued to publish their works but could not get used to the socrealist principles by the end of the 1930s, were executed on fabricated charges, Daniil Kharms and Alexander Vvedensky died in prison.[52][67]

The return from emigration such famous authors as Aleksey Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, and Ilya Ehrenburg was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets.

After his return to Russia Maxim Gorky was proclaimed by the Soviet authorities as "the founder of Socialist Realism". His novel Mother (1906), which Gorky himself considered one of his biggest failures, inspired proletarian writers to found the socrealist movement. Gorky defined socialist realism as the "realism of people who are rebuilding the world" and pointed out that it looks at the past "from the heights of the future's goals", although he defined it not as a strict style (which is studied in Andrei Sinyavsky's essay On Socialist Realism), but as a label for the "union of writers of styles", who write for one purpose, to help in the development of the new man in socialist society. Gorky became the initiator of creating the Writer's Union, a state organization, intended to unite the socrealist writers.[68] Despite the official reputation, Gorky's post-revolutionary works, such as the novel The Life of Klim Samgin (1925–1936) can't be defined as socrealist, but modernist.[69][66]

Andrei Bely (1880–1934), author of Petersburg (1913/1922), a well-known modernist writer, also was a member of Writer's Union and tried to become a "true" socrealist by writing a series of articles and making ideological revisions to his memoirs, and he also planned to begin a study of Socialist realism. However, he continued writing with his unique techniques.[70] Although he was actively published during his lifetime, his major works would not be reissued until the end of the 1970s.

Mikhail Sholokhov (1905–1984) was one of the most significant figures in the official Soviet literature. His main socrealist work is Virgin Soil Upturned (1935), a novel in which Sholokhov glorifies the collectivization. However, his best-known and the most significant literary achievement is Quiet Flows the Don (1928–1940), an epic novel which realistically depicts the life of Don Cossacks during the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and Russian Civil War.[52][71]

Nikolai Ostrovsky's novel How the Steel Was Tempered (1932–1934) has been among the most popular works of literary socrealism, with tens of millions of copies printed in many languages around the world. In China, various versions of the book have sold more than 10 million copies.[72] In Russia more than 35 million copies of the book are in circulation.[73] The book is a fictionalized autobiography of Ostrovsky's life: he had a difficult working-class childhood, became a Komsomol member in July 1919 and volunteered to join the Red Army. The novel's protagonist, Pavel Korchagin, represented the "young hero" of Russian literature: he is dedicated to his political causes, which help him to overcome his tragedies.[74] Alexander Fadeyev (1901–1956) was also a well-known Socialist realism writer, the chairman of the official Writer's Union during Stalinist era.[52][67] His novel The Rout (1927) deals with the partisan struggle in Russia's Far East during the Russian Revolution and Civil War of 1917–1922. Fadeyev described the theme of this novel as one of a revolution significantly transforming the masses.[52][67]

In the 1930s, Konstantin Paustovsky (1892–1968), an influenced by neo-Romantic works of Alexander Grin master of landscape prose, a singer of the Meshchera Lowlands, and already in the post-Stalin years a multiple nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature, joined the ranks of leading Soviet writers.fantastic.[75]

Novelist and playwright Leonid Leonov, despite the fact that he was considered by authorities to be one of the pillars of socialist realism,[76] during the Stalin years, created a forbidden novella about emigrats Eugenua Ivanovna (1938), a play about the Chekist purges, The Snowstorm (1940), briefly permitted and then also forbidden, and a novel, The Russian Forest (1953), where ecological issues were perhaps touched upon for the first time in Soviet literature. Over the course of forty years (1940–1994), he wrote a huge philosophical and mystical novel, "The Pyramid", which was finished and published in the year of the author's death.

Wait for me and I'll come back,

Escaping every fate!

‘Just got lucky!’ they will say,

Those that didn't wait.

They will never understand

How, amidst the strife,

By your waiting for me, dear,

You had saved my life!

—Konstantin Simonov, Wait for Me! (1941), translated by Mike Munford[77]

The cult figures of the literature of the Second World War were the war poets Konstantin Simonov, arguably most famous for his 1941 poem Wait for Me,[78] and Aleksandr Tvardovsky, author of the long poem Vasily Tyorkin (1941–45), chief editor of the literary magazine Novy Mir.[79]

Boris Polevoy is the author of the Story About a True Man (1946), based on the life of World War II fighter pilot Aleksey Maresyev, which was an immensely popular.[80]

Late Soviet era

So what is beauty? And why does the human race

Keep up its worship, whether valid or misguided?

Is it a vessel holding empty space,

Or is it fire shimmering inside it?

—Nikolay Zabolotsky, A Plain Girl (1955), translated by Alyona Mokraya[81]

After the end of World War II Nobel Prize-winning Boris Pasternak (1890–1960) wrote a novel Doctor Zhivago (1945–1955). Publication of the novel in Italy caused a scandal, as the Soviet authorities forced Pasternak to renounce his 1958 Nobel Prize and denounced as an internal White emigre and a Fascist fifth columnist. Pasternak was expelled from the Writer's Union.

The majority of members of the Writers' Union (Anatoly Rybakov, Sergey Zalygin, Anatoly Kalinin, Daniil Granin, Yuri Nagibin, Yury Trifonov, Chinghiz Aitmatov, Anatoly Ivanov, Pyotr Proskurin, Boris Yekimov, among many others) continued to work in the mainstream of Socialist Realism, not without criticizing certain phenomena of Soviet reality, such as showiness, mismanagement, nepotism, and widespread poaching. However, even in officially recognized literature, not entirely canonical movements of the poet-sixtiers, Lieutenant and Village Prose appear.

And however long the blizzard blows, whether it's three days or a week, every single day is counted as a day off, and the men are turned out to work Sunday after Sunday to make up for lost time.

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), translated by H. T. Willetts[82]

The Khrushchev Thaw (c. 1954 – c. 1964) brought some fresh wind to literature (the term was coined after Ilya Ehrenburg's 1954 novel The Thaw). Published in 1956, Vladimir Dudintsev's novel Not by Bread Alone became one of the main literary events of the Thaw and a milestone in the process of de-Stalinization, but was soon criticized and withdrawn from circulation.[62] The last years of life were fruitful for Nikolay Zabolotsky, who was repressed during the Stalin years. The publication in 1962 of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's debut story One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich about a political prisoner became a national and international sensation. Poetry of the Sixtiers or Russian New Wave became a mass-cultural phenomenon: Bella Akhmadulina, Victor Sosnora, Robert Rozhdestvensky, Andrei Voznesensky, and Yevgeny Yevtushenko, read their poems in stadiums and attracted huge crowds. Arseny Tarkovsky, Gleb Gorbovsky, Nikolay Rubtsov and Oleg Chukhontsev's lyrical poetry also stood apart from the socrealist mainstream.[62]

The Village Prose was a movement in Soviet literature beginning during the Khrushchev Thaw, which included works that cultivated nostalgia of rural life.[83][84] Valentin Ovechkin's story District Routine (1952), expose managerial inefficiency, the self-interest of party functionaries,[85] was the starting point of the movement.[86][87] Its major members Alexander Yashin, Fyodor Abramov, Boris Mozhayev, Viktor Astafyev, Vladimir Soloukhin, Vasily Shukshin, Vasily Belov, and Valentin Rasputin clustered in the traditionalist and nationalist Nash Sovremennik literary magazine.[88]

Since 1985/86, the Perestroika—a period of great changes in the political and cultural life in the USSR—gave way to a wide diversity of banned previously and new writings.[89][90][91] In 1986 there was established the legal non-Realistic literary club "Poetry", among its members were Dmitry Prigov, Igor Irtenyev, Aleksandr Yeryomenko, Sergey Gandlevsky, and Yuri Arabov. Many previously suppressed works were published, one of first, in 1987, Anatoly Rybakov's anti-Stalinist Children of the Arbat trilogy.

Soviet nonconformism

Some writers dared to oppose Soviet ideology, like short-story writer Varlam Shalamov (1907–1982) and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008), who wrote about life in the gulag camps, or Vasily Grossman (1905–1964), with his description of World War II events countering the Soviet official historiography (his epic novel Life and Fate (1959) was not published in the Soviet Union until the perestroika). Such writers, dubbed "dissidents", could not publish their major works until the 1960s.[92]

Modernist and Postmodern dissident literature[93] was related and partially coincided with the Soviet nonconformist art movement. Some poets were both artists or participants and inspirers of art groups, such as Evgenii Kropivnitsky (1893–1979), Igor Kholin, Genrikh Sapgir, Vilen Barskyi (1930–2012), Roald Mandelstam (1932–1961), Vsevolod Nekrasov (1934–2009), Igor Sinyavin (1937–2000), Alexei Khvostenko (1940–2004), Dmitry Prigov (1940–2007), Kari Unksova (1941–1983), Ry Nikonova (1942–2014), Oleg Grigoriev (1943–1992), Serge Segay (1947–2014), and Vladimir Sorokin (b. 1955).[94]

But the late 1950s thaw did not last long. In the 1970s, some of the most prominent authors were not only banned from publishing but were also prosecuted for their anti-Soviet sentiments, or for parasitism, thus writers Yuli Daniel (1925–1988) and Leonid Borodin (1938–2011) was imprisoned. Solzhenitsyn and Nobel Prize–winning poet Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996) were expelled from the country. Others, such as writers and poets Viktor Nekrasov (1911–1987), Lev Kopelev (1912–1997), Aleksandr Galich (1918–1977), Arkadiy Belinkov (1921–1970), Alexander Zinoviev (1922–2006), Naum Korzhavin (1925–2018), Andrei Sinyavsky (1925–1997), Vilen Barskyi, Georgi Vladimov (1931–2003), Vasily Aksyonov (1932–2009), Vladimir Voinovich (1932–2018), Anatoly Gladilin (1935–2018), Anri Volokhonsky (1936–2017), Andrei Bitov (1937–2018), Igor Sinyavin, Alexei Khvostenko, Sergei Dovlatov (1941–1990), Eduard Limonov (1943–2020), and Sasha Sokolov (b. 1943), had to emigrate to the West,[65] while Oleg Grigoriev and Venedikt Yerofeyev (1938–1990) "emigrated" to alcoholism, and repressed still in Stalinist years poet Yury Aikhenvald (1928–1993) with some others to translations, and Kari Unksova and Yury Dombrovsky (1909–1978) were murdered, Dombrovsky shortly after publishing his novel The Faculty of Useless Knowledge (1975). Their books were not published officially until the perestroika period of the 1980s, although fans continued to reprint them manually in a manner called "samizdat" (self-publishing).[95]

In 1960s arose unofficial Soviet Second Russian Avant-Garde and Russian postmodernism. In 1965–72, at Leningrad existed the avantgardist Absurdist poetic and writing group "Khelenkuts", which included Vladimir Erl and Aleksandr Mironov, among others. Andrei Bitov was Postmodernism first proponent. In 1970, Venedikt Erofeyev's surrealist postmodern prose poem Moscow-Petushki was published via samizdat.[96][97] The Soviet emigrant Sasha Sokolov wrote in 1980 the completely postmodern novel Between Dog and Wolf.[98] Since 70s there were such postmodern unofficial movements as Moscow Conceptualists with elements of concrete poetry[99][100] (Vsevolod Nekrasov, Dmitry Prigov, Lev Rubinstein, Timur Kibirov, early Vladimir Sorokin) and Metarealism, namely metaphysical realism, used complex metaphors which they called meta-metaphors (Konstantin Kedrov, Viktor Krivulin, Elena Katsyuba, Ivan Zhdanov, Elena Shvarts,[101] Vladimir Aristov, Aleksandr Yeryomenko, Yuri Arabov, Alexei Parshchikov).[102][103][104] Arkadii Dragomoshchenko is considered the foremost representative of the Language Poets in Russian literature.[105] In Yeysk, there was the "Transfurist" group of mixing verbal, sound and visual poetry (Ry Nikonova and Serge Segay, among others). The bunned from publishing Chuvash and Russian poet Gennadiy Aygi had been created experimental surrealist verses[92] as follows:

And we utter a few words — simply because

we’re scared of silence

and deem any movement dangerous

- Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Literature_of_Russia

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk