A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The Reverend Eckhart von Hochheim | |

|---|---|

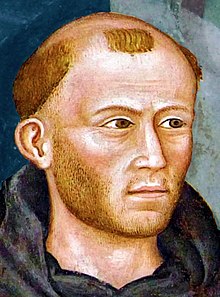

Postmortem portrait of Meister Eckhart | |

| Born | 1260 |

| Died | 1328 (aged 67–68) probably Avignon, Kingdom of Arles, Holy Roman Empire |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

Main interests | Religion, Spirituality, Theology |

Eckhart von Hochheim OP (c. 1260 – c. 1328),[1] commonly known as Meister Eckhart,[a] Master Eckhart or Eckehart, claimed original name Johannes Eckhart,[2] was a German Catholic theologian, philosopher and mystic, born near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia (now central Germany) in the Holy Roman Empire.[b]

Eckhart came into prominence during the Avignon Papacy at a time of increased tensions between monastic orders, diocesan clergy, the Franciscan Order, and Eckhart's Dominican Order. In later life, he was accused of heresy and brought up before the local Franciscan-led Inquisition, and tried as a heretic by Pope John XXII with the bull In Agro Dominico of March 27, 1329.[3].[c] He seems to have died before his verdict was received.[4][d]

He was well known for his work with pious lay groups such as the Friends of God and was succeeded by his more circumspect disciples Johannes Tauler and Henry Suso who was later beatified.[citation needed] Since the 19th century, he has received renewed attention. He has acquired a status as a great mystic within contemporary popular spirituality, as well as considerable interest from scholars situating him within the medieval scholastic and philosophical tradition.[6]

Early life

Eckhart was probably born around 1260 in the village of Tambach, near Gotha, in the Landgraviate of Thuringia,[7] perhaps between 1250 and 1260.[8] It was previously asserted that he was born to a noble family of landowners, but this originated in a misinterpretation of the archives of the period.[9] In reality, little is known about his family and early life. There is no basis for giving him the Christian name of Johannes, which sometimes appears in biographical sketches:[10] his Christian name was Eckhart; his surname was von Hochheim.[11]

Career

Probably around 1278 Eckhart joined the Dominican convent at Erfurt, when he was about eighteen. It is assumed he studied at Cologne before 1280.[12] He may have also studied at the University of Paris, either before or after his time in Cologne.[13]

The first solid evidence we have for his life is when on 18 April 1294, as a baccalaureus (lecturer) on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, a post to which he had presumably been appointed in 1293, he preached the Easter Sermon (the Sermo Paschalis) at the Dominican convent of St. Jacques in Paris. In late 1294, Eckhart was made Prior at Erfurt and Dominican Provincial of Thuringia in Germany. His earliest vernacular work, Reden der Unterweisung (The Talks of Instructions/Counsels on Discernment), a series of talks delivered to Dominican novices, dates from this time (c. 1295–1298).[14] In 1302, he was sent to Paris to take up the external Dominican chair of theology. He remained there until 1303. The short Parisian Questions date from this time.[15]

In late 1303, Eckhart returned to Erfurt and was given the position of Provincial superior for Saxony, a province which reached at that time from the Netherlands to Livonia. Thereby, he had responsibility for forty-seven convents in the region. Complaints made against the Provincial superior of Teutonia and him at the Dominican general chapter held in Paris in 1306, concerning irregularities among the ternaries, must have been trivial, because the general, Aymeric of Piacenza, appointed him in the following year as his vicar-general for Bohemia with full power to set the demoralised monasteries there in order. Eckhart was Provincial for Saxony until 1311, during which time he founded three convents for women there.[16]

On 14 May 1311 Eckhart was appointed by the general chapter held at Naples as teacher at Paris. To be invited back to Paris for a second stint as magister was a rare privilege, previously granted only to Thomas Aquinas.[17] Eckhart stayed in Paris for two academic years, until the summer of 1313, living in the same house as inquistor William of Paris. After that follows a long period of which it is known only that Eckhart spent part of the time at Strasbourg.[18] It is unclear what specific office he held there: he seems chiefly to have been concerned with spiritual direction and with preaching in convents of Dominicans.[19]

A passage in a chronicle of the year 1320, extant in manuscript (cf. Wilhelm Preger, i. 352–399), speaks of a prior Eckhart at Frankfurt who was suspected of heresy, and some historians have linked this to Meister Eckhart.

Accusation of heresy

In late 1323 or early 1324, Eckhart left Strasbourg for the Dominican house at Cologne. It is not clear exactly what he did there, though part of his time may have been spent teaching at the prestigious Studium in the city. Eckhart also continued to preach, addressing his sermons during a time of disarray among the clergy and monastic orders, rapid growth of numerous pious lay groups, and the Inquisition's continuing concerns over heretical movements throughout Europe.

It appears that some of the Dominican authorities already had concerns about Eckhart's teaching. The Dominican General Chapter held in Venice in the spring of 1325 had spoken out against "friars in Teutonia who say things in their sermons that can easily lead simple and uneducated people into error".[20] This concern (or perhaps concerns held by the archbishop of Cologne, Henry of Virneburg) may have been why Nicholas of Strasburg, to whom the Pope had given the temporary charge of the Dominican convents in Germany in 1325, conducted an investigation into Eckhart's orthodoxy. Nicholas presented a list of suspect passages from the Book of Consolation to Eckhart, who responded sometime between August 1325 and January 1326 with the treatise Requisitus, now lost, which convinced his immediate superiors of his orthodoxy.[20] Despite this assurance, however, the archbishop in 1326 ordered an inquisitorial trial.[19][21] At this point Eckhart issued a Vindicatory Document, providing chapter and verse of what he had been taught.[22]

Throughout the difficult months of late 1326, Eckhart had the full support of the local Dominican authorities, as evident in Nicholas of Strasbourg's three official protests against the actions of the inquisitors in January 1327.[23] On 13 February 1327, before the archbishop's inquisitors pronounced their sentence on Eckhart, Eckhart preached a sermon in the Dominican church at Cologne, and then had his secretary read out a public protestation of his innocence. He stated in his protest that he had always detested everything wrong, and should anything of the kind be found in his writings, he now retracts. Eckhart himself translated the text into German, so that his audience, the vernacular public, could understand it. The verdict then seems to have gone against Eckhart. Eckhart denied competence and authority to the inquisitors and the archbishop, and appealed to the Pope against the verdict.[21] He then, in the spring of 1327, set off for Avignon.

In Avignon, Pope John XXII seems to have set up two tribunals to inquire into the case, one of theologians and the other of cardinals.[23] Evidence of this process is thin. However, it is known that the commissions reduced the 150 suspect articles down to 28; the document known as the Votum Avenionense gives, in scholastic fashion, the twenty-eight articles, Eckhart's defence of each, and the rebuttal of the commissioners.[23] On 30 April 1328, the pope wrote to Archbishop Henry of Virneburg that the case against Eckhart was moving ahead, but added that Eckhart had already died (modern scholarship suggests he may have died on 28 January 1328).[24] The papal commission eventually confirmed (albeit in modified form) the decision of the Cologne commission against Eckhart.[19]

Pope John XXII issued a bull (In agro dominico), 27 March 1329, in which a series of statements from Eckhart is characterized as heretical, another as suspected of heresy.[25] At the close, it is stated that Eckhart recanted before his death everything which he had falsely taught, by subjecting himself and his writing to the decision of the Apostolic see. It is possible that the Pope's unusual decision to issue the bull, despite the death of Eckhart (and the fact that Eckhart was not being personally condemned as a heretic), was due to the pope's fear of the growing problem of mystical heresy, and pressure from his ally Henry of Virneburg to bring the case to a definite conclusion.[26]

Rehabilitation

Eckhart's status in the contemporary Catholic Church has been uncertain. The Dominican Order pressed in the last decade of the 20th century for his full rehabilitation and confirmation of his theological orthodoxy. Pope John Paul II voiced favorable opinion on this initiative, even going as far as quoting from Eckhart's writings, but the outcome was confined to the corridors of the Vatican. In the spring of 2010, it was revealed that there had been a response from the Vatican in a letter dated 1992. Timothy Radcliffe, then Master of the Dominicans and recipient of the letter, summarized the contents as follows:

We tried to have the censure lifted on Eckhart[27] ... and were told that there was really no need since he had never been condemned by name, just some propositions which he was supposed to have held, and so we are perfectly free to say that he is a good and orthodox theologian.[28]

Professor Winfried Trusen of Würzburg, a correspondent of Radcliffe, wrote in a defence of Eckhart to Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), stating:

Only 28 propositions were censured, but they were taken out of their context and impossible to verify, since there were no manuscripts in Avignon.[28]

Influences

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2017) |

Eckhart was schooled in medieval scholasticism and was well-acquainted with Aristotelianism and Augustinianism. The Neo-Platonism of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite asserted a great influence on him, as reflected in his notions on the Gottheit beyond the God who can be named.

Teachings

Sermons

Although he was an accomplished academic theologian, Eckhart's best-remembered works are his highly unusual sermons in the vernacular. Eckhart as a preaching friar attempted to guide his flock, as well as monks and nuns under his jurisdiction, with practical sermons on spiritual/psychological transformation and New Testament metaphorical content related to the creative power inherent in disinterest (dispassion or detachment).[citation needed]

The central theme of Eckhart's German sermons is the presence of God in the individual soul, and the dignity of the soul of the just man. Although he elaborated on this theme, he rarely departed from it. In one sermon, Eckhart gives the following summary of his message:

When I preach, I usually speak of detachment and say that a man should be empty of self and all things; and secondly, that he should be reconstructed in the simple good that God is; and thirdly, that he should consider the great aristocracy which God has set up in the soul, such that by means of it man may wonderfully attain to God; and fourthly, of the purity of the divine nature.[29]

As Eckhart said in his trial defence, his sermons were meant to inspire in listeners the desire above all to do some good.[citation needed] In this, he frequently used unusual language or seemed to stray from the path of orthodoxy, which made him suspect to the Church during the tense years of the Avignon Papacy.[citation needed]

Theology proper

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

In Eckhart's vision, God is primarily fecund. Out of overabundance of love the fertile God gives birth to the Son, the Word in all of us. Clearly,[e] this is rooted in the Neoplatonic notion of "ebullience; boiling over" of the One that cannot hold back its abundance of Being. Eckhart had imagined the creation not as a "compulsory" overflowing (a metaphor based on a common hydrodynamic picture), but as the free act of will of the triune nature of Deity (refer Trinitarianism).

Another bold assertion is Eckhart's distinction between God and Godhead (Gottheit in German, meaning Godhood or Godhead, state of being God). These notions had been present in Pseudo-Dionysius's writings and John the Scot's De divisione naturae, but Eckhart, with characteristic vigor and audacity, reshaped the germinal metaphors into profound images of polarity between the Unmanifest and Manifest Absolute.

Eckhart taught that "it is not in God to destroy anything which has being, but he perfects all things"[30] leading some scholars to conclude that he may have held to some form of universal salvation.[31]

Contemplative method

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

John Orme Mills notes that Eckhart did not "leave us a guide to the spiritual life like St Bonaventure’s Itinerarium – the Journey of the Soul," but that his ideas on this have to be condensed from his "couple of very short books on suffering and detachment" and sermons.[32] According to Mills, Eckhart's comments on prayer are only about contemplative prayer and "detachment."[32]

According to Reiner Schürmann, four stages can be discerned in Eckhart's understanding mystical development: dissimilarity, similarity, identity, breakthrough.[2]

Influence and study

13th century

Eckhart was one of the most influential 13th-century Christian Neoplatonists in his day, and remained widely read in the later Middle Ages.[33] Some early twentieth-century writers believed that Eckhart's work was forgotten by his fellow Dominicans soon after his death. In 1960, however, a manuscript ("in agro dominico") was discovered containing six hundred excerpts from Eckhart, clearly deriving from an original made in the Cologne Dominican convent after the promulgation of the bull condemning Eckhart's writings, as notations from the bull are inserted into the manuscript.[34] The manuscript came into the possession of the Carthusians in Basel, demonstrating that some Dominicans and Carthusians had continued to read Eckhart's work.

It is also clear that Nicholas of Cusa, Archbishop of Cologne in the 1430s and 1440s, engaged in extensive study of Eckhart. He assembled, and carefully annotated, a surviving collection of Eckhart's Latin works.[35] As Eckhart was the only medieval theologian tried before the Inquisition as a heretic, the subsequent (1329) condemnation of excerpts from his works cast a shadow over his reputation for some, but followers of Eckhart in the lay group Friends of God existed in communities across the region and carried on his ideas under the leadership of such priests as John Tauler and Henry Suso.[36]

Johannes Tauler and Rulman Merswin

Eckhart is considered by some to have been the inspirational "layman" referred to in Johannes Tauler's and Rulman Merswin's later writings in Strasbourg where he is known to have spent time (although it is doubtful that he authored the simplistic Book of the Nine Rocks published by Merswin and attributed to The Friend of God from the Oberland). On the other hand, most scholars consider The Friend of God from the Oberland to be a pure fiction invented by Merswin to hide his authorship because of the intimidating tactics of the Inquisition at the time.[citation needed]

Theologia Germanica and the Reformation

It has been suspected that his practical communication of the mystical path is behind the influential 14th-century "anonymous" Theologia Germanica, which was disseminated after his disappearance. According to the medieval introduction of the document, its author was an unnamed member of the Teutonic Order of Knights living in Frankfurt.[citation needed]

The lack of imprimatur from the Church and anonymity of the author of the Theologia Germanica did not lessen its influence for the next two centuries – including Martin Luther at the peak of public and clerical resistance to Catholic indulgences – and was viewed by some historians of the early 20th century as pivotal in provoking Luther's actions and the subsequent Protestant Reformation.[citation needed]

The following quote from the Theologia Germanica depicts the conflict between worldly and ecclesiastical affairs:[citation needed]

The two eyes of the soul of man cannot both perform their work at once: but if the soul shall see with the right eye into eternity, then the left eye must close itself and refrain from working, and be as though it were dead. For if the left eye be fulfilling its office toward outward things, that is holding converse with time and the creatures; then must the right eye be hindered in its working; that is, in its contemplation. Therefore, whosoever will have the one must let the other go; for "no man can serve two masters".[37]

Obscurity

Eckhart was largely forgotten from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, barring occasional interest from thinkers such as Angelus Silesius (1627–1677).[38] For centuries, his writings were known only from a number of sermons found in old editions of Johann Tauler's sermons, published by Kachelouen (Leipzig, 1498) and by Adam Petri (Basel, 1521 and 1522).

Rediscovery

Interest in Eckhart's works was revived in the early nineteenth century, especially by German Romantics and Idealist philosophers.[39][40][f] Franz Pfeiffer's publication in 1857 of Eckhart's German sermons and treatises added greatly to this interest.[42] Another important figure in the later nineteenth century for the recovery of Eckhart's works was Henry Denifle, who was the first to recover Eckhart's Latin works, from 1886 onwards.[43]

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, much Catholic interest in Eckhart was concerned with the consistency of his thought in relation to Neoscholastic thought – in other words, to see whether Eckhart's thought could be seen to be essentially in conformity with orthodoxy as represented by his fellow Dominican Thomas Aquinas.[44]

Attribution of works

Since the mid-nineteenth century scholars have questioned which of the many pieces attributed to Eckhart should be considered genuine, and whether greater weight should be given to works written in the vernacular, or Latin. Although the vernacular works survive today in over 200 manuscripts, the Latin writings are found only in a handful of manuscripts. Denifle and others have proposed that the Latin treatises, which Eckhart prepared for publication very carefully, were essential to a full understanding of Eckhart.[45]

In 1923, Eckhart's Essential Sermons, Commentaries, Treatises and Defense (also known as the Rechtsfertigung, or Vindicatory Document) was re-published. The Defense recorded Eckhart's responses against two of the Inquisitional proceedings brought against him at Cologne, and details of the circumstances of Eckhart's trial. The excerpts in the Defense from vernacular sermons and treatises described by Eckhart as his own, served to authenticate a number of the vernacular works.[46] Although questions remain about the authenticity of some vernacular works, there is no dispute about the genuine character of the Latin texts presented in the critical edition.[47]

Eckhart as a mystic

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Since the 1960s scholars have debated whether Eckhart should be called a "mystic".[48] The philosopher Karl Albert had already argued that Eckhart had to be placed in the tradition of philosophical mysticism of Parmenides and Plato and the neo-Platonist thinkers Plotinus, Porphyry and Proclus.[49] Heribert Fischer argued in the 1960s that Eckhart was a mediaeval theologian.[49] Most recently, Clint Johnson agreed with D. T. Suzuki and argued on the basis of Eckhart's appeals to experience that he is a mystic in the tradition of Augustine and Dionysius.[50] [51] Passages like the following, Johnson contends, point to experience beyond intellectual speculation and philosophizing:

Those who have never been familiar with inward things do not know what God is. Like a man who has wine in his cellar but has never tasted it, he does not know that it is good. (Sermon 10, DW I 164.5–8)[52]

Whoever does not understand what I say, let him not burden his heart with it. For as long as a man is not like this truth, he will not understand what I say. For this is a truth beyond thought that comes immediately from the heart of God. (Sermon 52, DW II 506.1–3)[52]

Kurt Flasch, a member of the so-called Bochum-school of mediaeval philosophy,[49] strongly reacted against the influence of New Age mysticism and "all kinds of emotional subjective mysticism", arguing for the need to free Eckhart from "the Mystical Flood".[49] He sees Eckhart strictly as a philosopher. Flasch argues that the opposition between "mystic" and "scholastic" is not relevant because this mysticism (in Eckhart's context) is penetrated by the spirit of the university, in which it occurred.[citation needed]

According to Hackett, Eckhart is to be understood as an "original hermeneutical thinker in the Latin tradition".[49] To understand Eckhart, he has to be properly placed within the western philosophical tradition of which he was a part. [53]

Josiah Royce, an objective idealist, saw Eckhart as a representative example of 13th and 14th century Catholic mystics "on the verge of pronounced heresy" but without original philosophical opinions. Royce attributes Eckhart's reputation for originality to the fact that he translated scholastic philosophy from Latin into German, and that Eckhart wrote about his speculations in German instead of Latin.[54]: 262, 265–266 Eckhart generally followed Thomas Aquinas's doctrine of the Trinity, but Eckhart exaggerated the scholastic distinction between the divine essence and the divine persons. The very heart of Eckhart's speculative mysticism, according to Royce, is that if, through what is called in Christian terminology the procession of the Son, the divine omniscience gets a complete expression in eternal terms, still there is even at the centre of this omniscience the necessary mystery of the divine essence itself, which neither generates nor is generated, and which is yet the source and fountain of all the divine. The Trinity is, for Eckhart, the revealed God and the mysterious origin of the Trinity is the Godhead, the absolute God.[54]: 279–282

Modern popularisation

Theology

Matthew Fox

Matthew Fox (born 1940) is an American theologian.[55] Formerly a priest and a member of the Dominican Order within the Roman Catholic Church, Fox was an early and influential exponent of a movement that came to be known as Creation Spirituality. The movement draws inspiration from the wisdom traditions of Christian scriptures and from the philosophies of such medieval Catholic visionaries as Hildegard of Bingen, Thomas Aquinas, Francis of Assisi, Julian of Norwich, Dante Alighieri, Meister Eckhart and Nicholas of Cusa, and others. Fox has written a number of articles on Eckhart[citation needed] and a book titled Breakthrough: Meister Eckhart's Creation Spirituality in New Translation.[56]

Modern philosophy

In "Conversation on a Country Path," Martin Heidegger develops his concept of Gelassenheit, or releasement, from Meister Eckhart.[57] Ian Moore argues "that Heidegger consulted Eckhart again and again throughout his career to develop or support his own thought.".[58]

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida distinguishes Eckhart's Negative Theology from his own concept of différance although John D. Caputo in his influential The Tears and Prayers of Jacques Derrida emphasises the importance of that tradition for this thought.[59]

Modern spiritualityedit

Meister Eckhart has become one of the timeless heroes of modern spirituality, which, to historian of religion[60] Wouter Hanegraaff, thrives on an all-inclusive syncretism.[61] This syncretism started with the colonisation of Asia, and the search of similarities between Eastern and Western religions.[62] Western monotheism was projected onto Eastern religiosity by Western orientalists, trying to accommodate Eastern religiosity to a Western understanding, whereafter Asian intellectuals used these projections as a starting point to propose the superiority of those Eastern religions.[62] Early on, the figure of Meister Eckhart has played a role in these developments and exchanges.[62]

Renewed academic attention to Eckhart has attracted favorable attention to his work from contemporary non-Christian mystics. Eckhart's most famous single quote, "The Eye with which I see God is the same Eye with which God sees me", is commonly cited by thinkers within neopaganism and ultimatist Buddhism as a point of contact between these traditions and Christian mysticism.

Schopenhaueredit

The first European translation of Upanishads appeared in two parts in 1801 and 1802.[62] The 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was influenced by the early translations of the Upanishads, which he called "the consolation of my life".[63][g] Schopenhauer compared Eckhart's views to the teachings of Indian, Christian and Islamic mystics and ascetics:

If we turn from the forms, produced by external circumstances, and go to the root of things, we shall find that Sakyamuni and Meister Eckhart teach the same thing; only that the former dared to express his ideas plainly and positively, whereas Eckhart is obliged to clothe them in the garment of the Christian myth, and to adapt his expressions thereto.[64]

Schopenhauer also stated:

Buddha, Eckhart, and I all teach essentially the same.[65]

Theosophical Societyedit

A major force in the mutual influence of Eastern and Western ideas and religiosity was the Theosophical Society,[66][67] which also incorporated Eckhart in its notion of Theosophy.[68] It searched for ancient wisdom in the East, spreading Eastern religious ideas in the West.[69] One of its salient features was the belief in "Masters of Wisdom",[70][h] "beings, human or once human, who have transcended the normal frontiers of knowledge, and who make their wisdom available to others".[70] The Theosophical Society also spread Western ideas in the East, aiding a modernisation of Eastern traditions, and contributing to a growing nationalism in the Asian colonies.[71]

Neo-Vedantaedit

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Meister_EckhartText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk