A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| Presidency of Richard Nixon January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974[1] | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Republican |

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| Library website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-vice presidency 36th Vice President of the United States Post-vice presidency 37th President of the United States

Judicial appointments

Policies

First term

Second term

Post-presidency Presidential campaigns Vice presidential campaigns

|

||

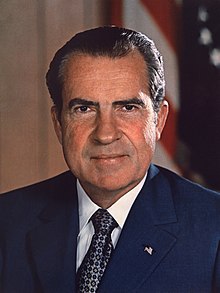

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment and removal from office, the only U.S. president ever to do so. He was succeeded by Gerald Ford, whom he had appointed vice president after Spiro Agnew became embroiled in a separate corruption scandal and was forced to resign. Nixon, a prominent member of the Republican Party from California who previously served as vice president for two terms under president Dwight D. Eisenhower, took office following his narrow victory over Democrat incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey and American Independent Party nominee George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election. Four years later, in the 1972 presidential election, he defeated Democrat nominee George McGovern, to win re-election in a landslide. Although he had built his reputation as a very active Republican campaigner, Nixon downplayed partisanship in his 1972 landslide re-election.

Nixon's primary focus while in office was on foreign affairs. He focused on détente with the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, easing Cold War tensions with both countries. As part of this policy, Nixon signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and SALT I, two landmark arms control treaties with the Soviet Union. Nixon promulgated the Nixon Doctrine, which called for indirect assistance by the United States rather than direct U.S. commitments as seen in the ongoing Vietnam War. After extensive negotiations with North Vietnam, Nixon withdrew the last U.S. soldiers from South Vietnam in 1973, ending the military draft that same year. To prevent the possibility of further U.S. intervention in Vietnam, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution over Nixon's veto.

In domestic affairs, Nixon advocated a policy of "New Federalism", in which federal powers and responsibilities would be shifted to state governments. However, he faced a Democratic Congress that did not share his goals and, in some cases, enacted legislation over his veto. Nixon's proposed reform of federal welfare programs did not pass Congress, but Congress did adopt one aspect of his proposal in the form of Supplemental Security Income, which provides aid to low-income individuals who are aged or disabled. The Nixon administration adopted a "low profile" on school desegregation, but the administration enforced court desegregation orders and implemented the first affirmative action plan in the United States. Nixon also presided over the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of major environmental laws like the Clean Water Act, although that law was vetoed by Nixon and passed by override. Economically, the Nixon years saw the start of a period of "stagflation" that would continue into the 1970s.

Nixon was far ahead in the polls in the 1972 presidential election, but during the campaign, Nixon operatives conducted several illegal operations designed to undermine the opposition. They were exposed when the break-in of the Democratic National Committee Headquarters ended in the arrest of five burglars and gave rise to a congressional investigation. Nixon denied any involvement in the break in, but, after a tape emerged revealing that Nixon had known about the White House connection to the Watergate burglaries shortly after they occurred, the House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings. Facing removal by Congress, Nixon resigned from office. Though some scholars believe that Nixon "has been excessively maligned for his faults and inadequately recognised for his virtues",[2] Nixon is generally ranked as a below average president in surveys of historians and political scientists.[3][4][5]

1968 election

Republican nomination

Richard Nixon had served as vice president from 1953 to 1961, and had been defeated in the 1960 presidential election by John F. Kennedy. In the years after his defeat, Nixon established himself as an important party leader who appealed to both moderates and conservatives.[6] Nixon entered the race for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination confident that, with the Democrats torn apart over the war in Vietnam, a Republican had a good chance of winning the presidency in November, although he expected the election to be as close as in 1960.[7] One year prior to the 1968 Republican National Convention the early favorite for the party's presidential nomination was Michigan governor George Romney, but Romney's campaign foundered on the issue of the Vietnam War.[8] Nixon established himself as the clear front-runner after a series of early primary victories. His chief rivals for the nomination were Governor Ronald Reagan of California, who commanded the loyalty of many conservatives, and Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, who had a strong following among party moderates.[9]

At the August Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, Reagan and Rockefeller discussed joining forces in a stop-Nixon movement, but the coalition never materialized and Nixon secured the nomination on the first ballot.[10] He selected Governor Spiro Agnew of Maryland as his running mate, a choice which Nixon believed would unite the party by appealing to both Northern moderates and Southerners disaffected with the Democrats.[11] The choice of Agnew was poorly received by many; a Washington Post editorial described Agnew as "the most eccentric political appointment since the Roman Emperor Caligula named his horse a consul.[12] In his acceptance speech, Nixon articulated a message of hope, stating, "We extend the hand of friendship to all people... And we work toward the goal of an open world, open sky, open cities, open hearts, open minds."[13]

General election

At the start of 1967, most Democrats expected that President Lyndon B. Johnson would be re-nominated. Those expectations were shattered by Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, who centered his campaign on opposition to Johnson's policies on the Vietnam War.[14] McCarthy narrowly lost to Johnson in the first Democratic Party primary on March 12 in New Hampshire, and the closeness of the results startled the party establishment and spurred Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York to enter the race. Two weeks later, Johnson told a stunned nation that he would not seek a second term. In the weeks that followed, much of the momentum that had been moving the McCarthy campaign forward shifted toward Kennedy.[15] Vice President Hubert Humphrey declared his own candidacy, drawing support from many of Johnson's supporters. Kennedy was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan in June 1968, leaving Humphrey and McCarthy as the two remaining major candidates in the race.[16] Humphrey won the presidential nomination at the August Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine was selected as his running mate. Outside the convention hall, thousands of young antiwar activists who had gathered to protest the Vietnam War clashed violently with police. The mayhem, which had been broadcast to the world in television, crippled the Humphrey campaign. Post-convention Labor Day surveys had Humphrey trailing Nixon by more than 20 percentage points.[17]

In addition to Nixon and Humphrey, the race was joined by former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, a vocal segregationist who ran on the American Independent Party ticket. Wallace held little hope of winning the election outright, but he hoped to deny either major party candidate a majority of the electoral vote, thus sending the election to the House of Representatives, where segregationist congressmen could extract concessions for their support.[18] The assassinations of Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., combined with disaffection towards the Vietnam War, the disturbances at the Democratic National Convention, and a series of city riots in various cities, made 1968 the most tumultuous year of the decade.[19] Throughout the year, Nixon portrayed himself as a figure of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval.[20] He appealed to what he later called the "silent majority" of socially conservative Americans who disliked the 1960s counterculture and the anti-war demonstrators.[21] Nixon waged a prominent television advertising campaign, meeting with supporters in front of cameras.[22] He promised "peace with honor" in the Vietnam War but did not release specifics of how he would accomplish this goal, resulting in media intimations that he must have a "secret plan".[23]

Humphrey's polling position improved in the final weeks of the campaign as he distanced himself from Johnson's Vietnam policies.[24] Johnson sought to conclude a peace agreement with North Vietnam in the week before the election; controversy remains over whether the Nixon campaign interfered with any ongoing negotiations between the Johnson administration and the South Vietnamese by engaging Anna Chennault, a prominent Chinese-American fundraiser for the Republican party.[25] Whether or not Nixon had any involvement, the peace talks collapsed shortly before the election, blunting Humphrey's momentum.[24]

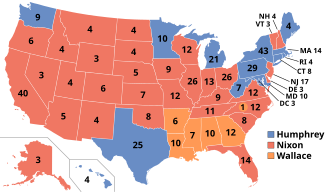

On election day, Nixon defeated Humphrey by about 500,000 votes, 43.4% to 42.7%; Wallace received 13.5% of the vote. Nixon secured 301 electoral votes to Humphrey's 191 and 46 for Wallace.[17][26] Nixon gained the support of many white ethnic and Southern white voters who traditionally had supported the Democratic Party, but he lost ground among African American voters.[27] In his victory speech, Nixon pledged that his administration would try to bring the divided nation together.[28] Despite Nixon's victory, Republicans failed to win control of either the House or the Senate in the concurrent congressional elections.[27]

Administration

Cabinet

For the major decisions of his presidency, Nixon relied on the Executive Office of the President rather than his Cabinet. Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman and adviser John Ehrlichman emerged as his two most influential staffers regarding domestic affairs, and much of Nixon's interaction with other staff members was conducted through Haldeman.[29] Early in Nixon's tenure, conservative economist Arthur F. Burns and liberal former Johnson administration official Daniel Patrick Moynihan served as important advisers, but both had left the White House by the end of 1970.[30] Conservative attorney Charles Colson also emerged as an important adviser after he joined the administration in late 1969.[31] Unlike many of his fellow Cabinet members, Attorney General John N. Mitchell held sway within the White House, and Mitchell led the search for Supreme Court nominees.[32] In foreign affairs, Nixon enhanced the importance of the National Security Council, which was led by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger.[29] Nixon's first Secretary of State, William P. Rogers, was largely sidelined during his tenure, and in 1973, Kissinger succeeded Rogers as Secretary of State while continuing to serve as National Security Advisor. Nixon presided over the reorganization of the Bureau of the Budget into the more powerful Office of Management and Budget, further concentrating executive power in the White House.[29] He also created the Domestic Council, an organization charged with coordinating and formulating domestic policy.[33] Nixon attempted to centralize control over the intelligence agencies, but he was generally unsuccessful, in part due to pushback from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.[34]

Despite his centralization of power in the White House, Nixon allowed his cabinet officials great leeway in setting domestic policy in subjects he was not strongly interested in, such as environmental policy.[35] In a 1970 memo to top aides, he stated that in domestic areas other than crime, school integration, and economic issues, "I am only interested when we make a major breakthrough or have a major failure. Otherwise don't bother me."[36] Nixon recruited former campaign rival George Romney to serve as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, but Romney and Secretary of Transportation John Volpe quickly fell out of favor as Nixon attempted to cut the budgets of their respective departments.[37] Nixon did not appoint any female or African American cabinet officials, although Nixon did offer a cabinet position to civil rights leader Whitney Young.[38] Nixon's initial cabinet also contained an unusually small number of Ivy League graduates, with the notable exceptions of George P. Shultz and Elliot Richardson, who each held three different cabinet positions during Nixon's presidency.[39] Nixon attempted to recruit a prominent Democrat like Humphrey or Sargent Shriver into his administration, but was unsuccessful until early 1971, when former Governor John Connally of Texas became Secretary of the Treasury.[38] Connally would become one of the most powerful members of the cabinet and coordinated the administration's economic policies.[40]

In 1973, as the Watergate scandal came to light, Nixon accepted the resignations of Haldeman, Erlichman, and Mitchell's successor as Attorney General, Richard Kleindienst.[41] Haldeman was succeeded by Alexander Haig, who became the dominant figure in the White House during the last months of Nixon's presidency.[42]

Vice presidency

As the Watergate scandal heated up in mid-1973, Vice President Spiro Agnew became a target in an unrelated investigation of corruption in Baltimore County, Maryland of public officials and architects, engineering, and paving contractors. He was accused of accepting kickbacks in exchange for contracts while serving as Baltimore County Executive, then when he was Governor of Maryland and Vice President.[43]

On October 10, 1973, Agnew pleaded no contest to tax evasion and became the second Vice President after John C. Calhoun to resign from office.[43] Nixon used his authority under the 25th Amendment to nominate Gerald Ford for vice president. The well-respected Ford was confirmed by Congress and took office on December 6, 1973.[44][45] This represented the first time that an intra-term vacancy in the office of vice president was filled. The Speaker of the House, Carl Albert from Oklahoma, was next in line to the presidency during the 57-day vacancy.

Judicial appointments

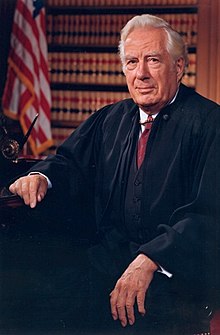

Nixon made four successful appointments to the Supreme Court while in office, shifting the Court in a more conservative direction following the era of the liberal Warren Court.[46] Nixon took office with one pending vacancy, as the Senate had rejected President Johnson's nomination of Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed retiring Chief Justice Earl Warren. Months after taking office, Nixon nominated federal appellate judge Warren E. Burger to succeed Warren, and the U.S. Senate quickly confirmed him. Another vacancy arose in 1969 after Fortas resigned from the Court, partially due to pressure from Attorney General Mitchell and other Republicans who criticized him for accepting compensation from financier Louis Wolfson.[47] To replace Fortas, Nixon successively nominated two Southern federal appellate judges, Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell, but both were rejected by the Senate. Nixon then nominated federal appellate judge Harry Blackmun, who was confirmed by the Senate in 1970.[48]

The retirements of Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II created two Supreme Court vacancies in late 1971. One of Nixon's nominees, corporate attorney Lewis F. Powell Jr., was easily confirmed. Nixon's other 1971 Supreme Court nominee, Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist, faced significant resistance from liberal Senators, but he was ultimately confirmed.[48] Burger, Powell, and Rehnquist all compiled a conservative voting record on the Court, while Blackmun moved to the left during his tenure. Rehnquist would later succeed Burger as chief justice in 1986.[46] Nixon appointed a total of 231 federal judges, surpassing the previous record of 193 set by Franklin D. Roosevelt. In addition to his four Supreme Court appointments, Nixon appointed 46 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 181 judges to the United States district courts.

Domestic affairs

Economy

| Fiscal Year |

Receipts | Outlays | Surplus/ Deficit |

GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[50] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 186.9 | 183.6 | 3.2 | 980.3 | 28.4 |

| 1970 | 192.8 | 195.6 | −2.8 | 1,046.7 | 27.1 |

| 1971 | 187.1 | 210.2 | −23.0 | 1,116.6 | 27.1 |

| 1972 | 207.3 | 230.7 | −23.4 | 1,216.3 | 26.5 |

| 1973 | 230.8 | 245.7 | −14.9 | 1,352.7 | 25.2 |

| 1974 | 263.2 | 269.4 | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Nixon_Administration