A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Propaganda in China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

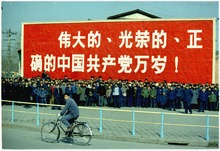

A large sign featuring a propaganda slogan in 1972: "Long Live the Great, Glorious, and Correct Communist Party of China!" | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华人民共和国宣传活动 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華人民共和國宣傳活動 | ||||||

| |||||||

Propaganda in China is used by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and historically by the Kuomintang (KMT), to sway domestic and international opinion in favor of its policies.[1][2] Domestically, this includes censorship of proscribed views and an active promotion of views that favor the government. Propaganda is considered central to the operation of the CCP and the Chinese government,[3] with propaganda operations in the country being directed by the CCP's Central Propaganda Department.

Aspects of propaganda can be traced back to the earliest periods of Chinese history, but propaganda has been most effective in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries owing to mass media and an authoritarian government.[3] The earliest Chinese propaganda tool also was an important tool in legitimizing the Kuomintang controlled Republic of China government that retreated from mainland China to Taiwan in 1949.

Propaganda during the Mao era was known for its constant use of mass campaigns to legitimize the party and the policies of leaders. It was the first time the CCP successfully made use of modern mass propaganda techniques, adapting them to the needs of a country which had a largely rural and illiterate population.[3] Today, propaganda in China is usually depicted through cultivation of the economy and Chinese nationalism.[4][needs update]

Terminology

| Xuanchuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 宣傳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 宣传 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | spread transmit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 선전 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 宣伝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | せんでん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

While the English word usually has a pejorative connotation, the Chinese word xuānchuán (宣传 "propaganda; publicity", composed of xuan 宣 "declare; proclaim; announce" and chuan 傳 or 传 "pass; hand down; impart; teach; spread; infect; be contagious"[5]) The term can have either a neutral connotation in official government contexts or a pejorative one in informal contexts. The term is not used for censorship, as it might connote in other parts of the world.[6]

Xuānchuán first appeared in the 3rd-century historical text Records of the Three Kingdoms where its usage referred to the dissemination of military skills.[7]: 6 In pre-modern times, the term was used to refer to dissemination of ideas and information by ruling elites.[8]: 103 The meaning of "to explain something to someone, or to conduct education" might first appeared in Ge Hong's (c. 320) Baopuzi criticism of effete scholars who Emperor Zhang of Han (r. 75–88) extravagantly rewarded.

These various gentlemen were heaped with honors, but not because they could breach walls or fight in the fields, break through an enemy's lines and extend frontiers, fall ill and resign office, pray for a plan of confederation and give the credit to others, or possess a zeal transcending all bounds. Merely because they expounded an interpretation of one solitary classic, such were the honors lavished upon them. And they were only lecturing upon words bequeathed by the dead. Despite their own high positions, emperors and kings deigned to serve these teachers.[9][non-primary source needed]

It was chosen to translate the Marxist-Leninist concept of Russian propagánda пропаганда in the early 20th-century China. Some xuanchuan collocations usually refer to "propaganda" (e.g., xuānchuánzhàn 宣传战 "propaganda war"), others to "publicity" (xuānchuán méijiè 宣传媒介 "mass media; means of publicity"), and still others are ambiguous (xuānchuányuán 宣传员 "propagandist; publicist").[10] The term xuanchuan also conveys the meaning of education, whereas the English word propaganda does not.[11]: 34

During the 20th century, use of the term propaganda in China approximated its meaning in early modern Europe, "to propagate what one believes to be true."[7]: 19 Operating according to this terminology, the CCP is open about the importance of its propaganda work, which it views as having a positive impact on informing the Chinese people and promoting social harmony.[12]: 106 David Shambaugh,[13]: 29 the scholar of Chinese politics and foreign policy, describes "proactive propaganda" in which the Chinese Communist Party Propaganda Department writes and disseminates information that it believes "should be used in educating and shaping society". In this particular context, xuanchuan "does not carry negative connotations for the CCP, nor, for that matter, for most Chinese citizens." The sinologist and anthropologist Andrew B. Kipnis says unlike English propaganda, Chinese xuanchuan is officially represented as language that is good for the nation as a whole.[14]: 119 However, the CCP is also sensitive to the negative connotations of the English word propaganda, and the commonly used Chinese term xuanchuan acquired pejorative connotations.[15]: 4 In 1992, Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin asked one of the CCP's most senior translators to come up with a better English alternative to propaganda as the translation of xuanchuan for propaganda targeting foreign audiences.[16]: 125 Replacement English translations include publicity, information, and political communication domestically,[17] or media diplomacy and cultural exchange internationally.[18]

History

Republican era

Because the national government of this time was weak, it was difficult for any censorship or propagandistic measures to be carried out effectively. However, a bureau was set up to control the production and release of film in China. Also, newspapers unfavorable to the central government could be harassed at will. After the Northern Expedition, the power of the central government increased significantly, and propaganda campaigns became more effective.

Lai Manwai's film documenting the Northern Expedition and Chiang Kai-shek's consolidation of power, produced by Lai's production company Minxin, was approved by the Nationalist Party branch in Shanghai as the only long-format film for party propaganda.[8]: 54 This made it one of the first party films in China.[8]: 54

Zheng Junli's 1941 film Long Live the Nations (Minzu wansui) was the first Chinese propaganda film aimed at developing solidarity among the ethnic minorities living in China's border regions.[8]: 106 The film was produced through the Nationalist-controlled China Motion Picture Studio.[8]: 106

Propaganda during the Chinese Civil War was directed against the CCP and the Japanese.[19][page needed] During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Nationalists had mobile projectionists travel in rural China to play anti-Japanese propaganda films.[7]: 46 Occupying Japanese authorities likewise had mobile projectionists show propaganda films in the areas of China under their control.[7]: 69

Mao era

The origins of the CCP propaganda system can be traced to Yan'an Rectification Movement and the rectification movements carried out there.[20] Following which it became a key mechanism in the Party's campaigns.[2][21] Mao explicitly laid out the political role of culture in his 1942 "Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Art and Literature". The propaganda system, considered a central part of CCP's "control system",[2][22] drew much from Soviet, Nazi, imperial China, Nationalist China, and other totalitarian states' propaganda methods.[2] It represented a quintessential Leninist "transmission belt" for indoctrination and mass mobilization.[2] David Shambaugh observes that propaganda and indoctrination are considered to have been a hallmark of the Maoist China;[2] the CCP employed a variety of "thought control" techniques, including incarceration for "thought reform," construction of role models to be emulated, mass mobilization campaigns, the creation of ideological monitors and propaganda teams for indoctrination purposes, enactment of articles to be memorized, control of the educational system and media, a nationwide system of loudspeakers, among other methods.[2] While ostensibly aspiring to a "Communist utopia," often had a negative focus on constantly searching for enemies among the people. The means of persuasion was often extremely violent, "a literal acting out of class struggle."[23]

Chinese authorities sought to promote model workers and soldiers whose productive examples were promoted to the public via radio, radio, and other media.[24]: 24

In 1951, a directive to develop a nationwide propaganda network designated individuals in each school, factory, and work unit as propaganda workers.[7]: 48

In the 1960s, Chinese propaganda sought to portray contrasting images of the United States government and the United States public.[25]: 17 Propaganda sought to criticize the government for its war in Vietnam while praising the public for anti-war protests.[25]: 17 As part of propaganda efforts during the 1965 Resist America, Aid Vietnam Campaign, the CCP organized street demonstrations and marches and promoted campaign messages using cultural media like film and photography exhibitions, chorus contests, and street performance.[25]: 29

According to academic Anne-Marie Brady, CCP propaganda and thought work (sīxiǎng gōngzuò 思想工作) traditionally had a much broader notion of the public sphere than is usually defined by media specialists.[23] Chinese propagandists used every possible means of communication available in China after 1949, including electronic media such as film and television, educational curriculum and research, print media such as newspapers and posters, cultural arts such as plays and music, oral media such as memorizing Mao quotes, as well as thought reform and political study classes.[23] In rural China, traveling drama troupes did propaganda work and were particularly important during land reform and other mass campaigns.[7]: 48 In 1955, the Ministry of Culture sought to develop rural cultural networks to distribute media like other performances, lantern slides, books, cinema, radio, books, and to establish newspaper reading groups.[7]: 48 Salaried workers at rural cultural centers toured the countryside distributing propaganda materials, teaching revolutionary songs, and the like.[7]: 48

China Central Television (CCTV) has traditionally served as a major national conduit for televised propaganda, while the People's Daily, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, has served as a medium for print propaganda. During the Mao era, a distinctive feature of propaganda and thought work was "rule by editorial," according to Brady. Political campaigns would be launched through editorials and leading articles in People's Daily, which would be followed by other papers.[23] Work units and other organizational political study groups utilized these articles as a source for political study, and reading newspapers in China was "a political obligation". Mao used Lenin's model for the media, which had it function as a tool of mass propaganda, agitation, and organization.[23]

During the Cultural Revolution, CCP propaganda was crucial to intensification of Mao Zedong's cult of personality, as well as mobilizing popular participation in national campaigns.[26] Past propaganda also encouraged the Chinese people to emulate government approved model workers and soldiers, such as Lei Feng, Chinese Civil War hero Dong Cunrui, Korean War hero Yang Gensi, and Dr. Norman Bethune, a Canadian doctor who assisted the CCP Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It also praised Third World revolutionaries and close foreign allies such as Albania and North Korea while vilifying both the American "imperialists" and the Soviet "revisionists" (the latter of whom was seen as having betrayed Marxism–Leninism following the Sino-Soviet split).

According to Barbara Mittler, Mao propaganda left memories of violence and slander upon many Chinese, and their psychological strains drove many to madness and death.[27] Today, Mao propaganda is no longer used by the CCP, and are largely commercialized for the purposes of nostalgia.[28]

Modern era

Following the death of Chairman Mao in 1976, propaganda was used to blacken the character of the Gang of Four, which was blamed for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. During the era of economic reform and modernization that was initiated by Deng Xiaoping, propaganda promoting socialism with Chinese characteristics was distributed. The first post-Mao campaign was in 1983 which saw the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign.

In 1977, Deng initiated a propaganda campaign to promote science as the cornerstone of China's modernization, in advance of the 1978 National Science Conference.[25]: 82 The campaign helped advanced Deng's efforts to improve the quality of science in China, particularly basic research, following the Cultural Revolution.[25]: 82 Chinese Academy of Sciences vice president Fang Yi led the campaign in having schools, factories, and communes organize youth-focused events to celebrate science and technology.[25]: 82

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were an indication to many elders in the CCP that liberalization in the propaganda sector had gone too far, and that the Party must re-establish its control over ideology and the propaganda system.[23]

Brady writes that propaganda and thought work have become the "life blood" of the Party-State since the post-1989 period, and one of the key means for guaranteeing the CCP's continued legitimacy and hold on power.[23]

In the 1990s, propaganda theorists described the challenges to China's propaganda and thought work as "blind spots"; mass communication was advocated as the antidote. From the early 1990s, selective concepts from mass communications theory, public relations, advertising, social psychology, patriotic education and other areas of modern mass persuasion were introduced into China's propaganda system for the purpose of creating a modern propaganda model.[23]

Particularly since the 1990s, China has engaged in propaganda seeking to eliminate the traditional son preference.[29]: 6–10

Recent developments

The 2008 Summer Olympics were portrayed by the Chinese government as a symbol of China's pride and place in the world,[30] and seem to have bolstered some domestic support for the Chinese government, and support for the policies of the CCP, giving rise to concerns that the state will possibly have more leverage to disperse dissent.[31] In the lead-up to the Olympics, the government allegedly issued guidelines to the local media for their reporting during the Games: most political issues not directly related to the games were to be downplayed; topics such as pro-Tibetan independence and East Turkestan movements were not to be reported on, as were food safety issues such as "cancer-causing mineral water."[32] As the 2008 Chinese milk scandal broke in September 2008, there was widespread speculation that China's desire for a perfect Games may have been a factor contributing towards the delayed recall of contaminated infant formula.[33][34]

In early 2009, the CCP embarked on a multibillion-dollar global media expansion, including the 24-hour English-language news channel China Global Television Network (CGTN) in the style of Western news agencies. According to Nicholas Bequelin, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, it was part of CCP general secretary Hu Jintao's plan to "go global" and make "the voice of China better heard in international affairs", by strengthening their foreign-language services, and being less political in their broadcasting. Bequelin notes that their function is to channel a specific view of China to an international audience, and their fundamental premise remains the same; that all information broadcast must reflect the government's views. The Chinese government encouraged the adaption of Western style media marketing in their news agencies due to internal competition with national commercial media.[35]

In 2011, then Chongqing party secretary Bo Xilai and the city's Propaganda Department initiated a 'Red Songs campaign' that demanded every district, government departments and commercial corporations, universities and schools, state radio and TV stations to begin singing "red songs", praising the achievements of the CCP and PRC. Bo said the aim was "to reinvigorate the city with the Marxist ideals of his father's comrade-in-arms Mao Zedong"; although academic Ding Xueliang of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology suspected the campaign's aim was to further his political standing within the country's leadership.[36][37][38][39]

Since Xi Jinping became in 2012 the CCP general secretary, censorship and propaganda have been significantly stepped up.[40][41] During a visit to Chinese state media, Xi stated that "party-owned media must hold the family name of the party" and that the state media "must embody the party's will, safeguard the party's authority".[42] In 2018, as part of an overhaul of CCP and government bodies, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT) was renamed into the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) with its film, news media and publications being transferred to the Central Propaganda Department.[43] Additionally, the control of China Central Television (CCTV, including its international edition, China Global Television), China National Radio (CNR) and China Radio International (CRI) were transferred to the newly established China Media Group (CMG) under the control of the Central Propaganda Department.[43][44]

Starting in June 2021 and continuing through at least 2024, China's judicial system has engaged in a propaganda campaign to promote court cases decided in favor of platform economy workers against the companies for which they did work.[45]: 182–183 The judicial system's newspapers and magazines have promoted coverage of typical cases and relevant studies.[45]: 182–183 Academic Angela Huyue Zhang writes that because court rulings in China do not create precedent, the campaign is a mechanism for guiding courts to tighten regulation in this area, particularly where platform workers lack contracts or have been characterized as independent contractors but are in fact subject to tight monitoring by the platform companies that dispatch them.[45]: 183

Xinjiang

During the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, CCP officials moved swiftly in a public relations campaign. According to Newsweek, CCP officials felt that the recent riots risked tarnishing China's global image, and underwent a public relations program involving quickly getting out the government's official version of the events, as well as transporting foreign journalists to riot affected areas. The growth in new technologies, such as email and SMS, forced the CCP's hand into taking up spin.

Since 2017, the Chinese government has engaged in a propaganda campaign to defend its actions in Xinjiang.[46][47][48][49] China initially denied the existence of the Xinjiang internment camps and attempted to cover-up their existence.[50] In 2018, after being forced to admit by widespread reporting that the Xinjiang internment camps exist, the Chinese government initiated a propaganda campaign to portray the camps as humane and to deny human rights abuses occur in Xinjiang.[51] In 2020 and 2021 they expanded the propaganda campaign due to international backlash against government policies in Xinjiang[52] and worries that the Chinese government no longer had control of the narrative.[50]

The Chinese government has used social media as a part of its extensive propaganda campaign.[47][53][54][55] Douyin, the mainland Chinese sister app to ByteDance-owned social media app TikTok, presents users with significant amounts of Chinese state propaganda pertaining to the human rights abuses in Xinjiang.[53][56][57]

Chinese government propaganda attacks have targeted international journalists covering human rights abuses in Xinjiang.[58][59][60] After providing coverage critical of Chinese government abuses in Xinjiang, BBC News reporter John Sudworth was subjected to a campaign of propaganda and harassment by Chinese state-affiliated and CCP-affiliated media.[58][61][62] The public attacks resulted in Sudworth and his wife Yvonne Murray, who reports for Raidió Teilifís Éireann, fleeing China for Taiwan for fear of their safety.[61][63]

Between July 2019 and early August 2019, the CCP-owned tabloid Global Times paid Twitter to promote tweets that deny that the Chinese government is committing human rights abuses in Xinjiang; Twitter later banned advertising from state-controlled media outlets on 19 August after removing large numbers of pro-Beijing bots from the social network.[64][65] China has spent heavily to purchase Facebook advertisements in order to spread propaganda designed to incite doubt on the existence and scope of human rights violations occurring within Xinjiang.[47][55][66]

In April 2021, the Chinese government released propaganda videos titled, "Xinjiang is a Wonderful Land", and produced a musical titled "The Wings of Songs" in order to portray Xinjiang as harmonious and peaceful.[46][67][48] The Wings of Songs portrays an idyllic rural landscape with a cohesive ethnic population notably devoid of repression, surveillance, and Islam.[68] It is near impossible to get accurate information about the situation in Xinjiang domestically in China,[69] concerns within the domestic audience are also downplayed because many aspects of the abuse such as forced labor are seen as commonplace by many Chinese citizens.[70] In 2021, Chinese officials ordered videos of Uyghur men and women saying that they deny the U.S. charges that China that is committing human rights violations.[71]

Critics have said that government propaganda plays into existing colonial and racist tropes about the Uyghurs by depicting them as dangerous or backwards. Domestic propaganda has increased since the international community began considering designating the abuses against the Uyghurs as a genocide. Domestic pushback against the genocide label is also emotional and follows a similar pattern of denial to the genocide committed against the Native Americans.[70]

COVID-19 pandemic

In 2020, CCP general secretary Xi Jinping and the rest of the CCP began propagating the idea of "winning a battle against America" in containing the coronavirus pandemic. The numbers are notably misrepresented by Chinese authorities, but the CCP has continued to take to the media, pointing out "the failures of America", even though the numbers are manipulated. The now former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accused the CCP of spreading disinformation on 17 March. Chinese officials in Japan have referred to the disease as the "Japanese coronavirus", even though there is no such evidence it originated there. The CCP has also used transmitting "positive energy" to promote itself.[72][73][74] After Mike Pompeo's accusation that the virus originated in a lab in Wuhan, which Anthony Fauci denied on 5 May, Chinese officials launched a smear campaign on the same day against him with multiple propaganda outlets calling him a liar.[75] During the George Floyd protests, the CCP criticized the US for failing to address racial equality. On 30 May 2020, Morgan Ortagus urged on Twitter for "freedom loving people" to hold the CCP to impose plans on Hong Kong for national security legislation. Her counterpart, Hua Chunying, responded back with "I can't breathe", obviously a reference to Floyd's last words. Some people responded with "I can't tweet" and some have accused the government of using the same police brutality tactics that killed Floyd, with Chinese censors simply deleting the complaints.[76] In Wuhan, where the outbreak first emerged, television shows and documentaries portrayed the response positively, as a heroic success taken care of by "warriors in white coats".[77] Alexander Kekulé's theory of coronavirus-disease 2019 coming from Italy instead of Wuhan which was taken out of context has sparked Chinese propaganda newspapers following the narrative, with even one headline saying, "China is Innocent!" Kekulé himself says it is pure propaganda.[78] State-owned outlets such as Xinhua and the People's Daily have blamed elderly deaths in Norway and Germany on COVID-19 vaccines, even though there is no scientific evidence, and have accused English media of downplaying it.[79]

In 2020, propaganda from China has been controlled by state media and CCP-run outlets such as the nationalistic tabloid Global Times, which portray the handling of COVID-19 as a success.[80] On 11 June 2020, Twitter announced that they deleted over 170,000 accounts tied to a Chinese-state linked operation because they were spreading false information about the COVID-19 pandemic.[81] On 22 June 2020, the United States Department of State designated several Chinese state media outlets as foreign missions.[82] In December 2020, an investigation by The New York Times and ProPublica revealed leaked internal documents showing the state's instructions to local media regarding the death of Li Wenliang. The documents address news organizations and social media platforms, ordering them to stop using push notifications, make no comment on the situation and control any discussion of the event happening in online spaces. The documents also address "local propaganda workers", demanding they steer online discussions away from anything that "seriously damages party and government credibility and attacks the political system".[83] Pro-Chinese government spam networks also attempted to discredit U.S. vaccines.[84]

On the 29th of April 2020, an animated video was posted on Twitter and YouTube, called Once Upon a Virus, used Lego figures to represent China through hospital workers and Lady Liberty representing America, was posted by Xinhua News Agency. The Lego Group, for their part, said they had nothing to do with the video in question. In the video, the hospital worker repeatedly warns the US about the outbreak, but they dismiss them, talking about lockdowns being a violation of human rights, or paywalls. By that point, Lady Liberty is hooked up to an IV and looks severely ill, and at the end, the US says "We are always correct, even when we contradict ourselves", and China responds with "That's what I love best about you Americans, your consistency". The Chinese government delayed warning the public about the outbreak, even as doctors tried to warn people via social media. The Associated Press reports "China's rigid controls on information, bureaucratic hurdles and a reluctance to send bad news up the chain of command muffled early warnings".[85]

100th Anniversary of CCP

In 2021 the state orchestrated a propaganda and information control campaign to bolster the 100th Anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party.[86] Chinese state owned media claimed without evidence that the CIA was recruiting Chinese-speaking spies, an assertion which went viral in the Chinese internet.[87] In 2021, the Ministry of Education of China announced that CCP general secretary Xi Jinping's socio-political policies and ideas would be included in the curriculum from primary school up to university level.[88] The 4-volume Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era textbooks for primary, secondary and tertiary school students were subsequently introduced in the new school year in 2021,[89] educators were instructed to "plant the seeds of loving the party, the country and socialism in young hearts".[88] This has led to comparisons of the cults of personality cultivated by Xi Jinping and Mao Zedong.[90][89][91]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chinese diplomats, government agencies, and state-controlled media in China have adopted a sympathetic view of Russia, while emphasizing that the war was caused by the United States and NATO.[92][93][94]

On the eve of the attack, Shimian, a digital outlet owned by newspaper Beijing News, accidentally posted an internal memo of the Chinese Cybersecurity Agency to media outlets. The outlets were told to "publish neither information favorable to the United States nor critiques of Russia", the media were also tasked to censor user comments and trend hashtags released by the three state-owned media, Xinhua News Agency, China Central Television (CCTV) and the People's Daily.[95][96][97]

Xinhua, CCTV and Global Times often posted unverified news from Russian state-controlled network RT, that were later proven to be erroneous; examples of which were when Global Times posted a video saying that a large number of Ukrainian soldiers had surrendered, or when CCTV reported that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy had fled Kyiv during the initial stages of the war.[98][99][100] In the midst of the invasion, China Global Television Network (CGTN) interviewed Denis Pushilin, a Ukrainian separatist leader, who claimed that the "vast majority of citizens want to be as close to Russia as possible".[99] CCTV also censored the live speech of Andrew Parsons, president of the International Paralympic Committee, during the opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Paralympics held in Beijing, as he condemned the war and called for diplomacy.[101]

Besides official state media channels, private Chinese tech giants such as Tencent, Sina Weibo and ByteDance[102] also amplified conspiracy theories created by Russian state media, such as the false claims of nefarious US biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine[103][104] and propagating the notion that Ukrainian government consists of neo-Nazis[105][106] and that the Ukrainian army were sabotaging their own nuclear plant.[107] Chinese streaming platform iQiyi also cancelled the broadcast of the English Premiere League to avoid showing the football teams' support for Ukraine.[108]

There were also numerous reports of censorship of anti-war comments by Chinese academics, celebrities and micro-influencers on social media.[109][106]

Mechanics

|

|---|