A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| River Trent | |

|---|---|

Trent Bridge, with Nottingham in the background | |

Drainage basin of the River Trent (Interactive map) | |

| Location | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Country within the UK | England |

| Counties | Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Yorkshire |

| Cities | Stoke-on-Trent, Nottingham |

| Towns | Stone, Rugeley, Burton upon Trent, Newark-on-Trent, Gainsborough |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Biddulph Moor, Staffordshire, England |

| • coordinates | 53°06′58″N 02°08′25″W / 53.11611°N 2.14028°W |

| • elevation | 275 m (902 ft) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Trent Falls, Humber Estuary, Lincolnshire, England |

• coordinates | 53°42′03″N 00°41′28″W / 53.70083°N 0.69111°W |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 298 km (185 mi) |

| Basin size | 10,435 km2 (4,029 sq mi)[1][a] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Colwick[3] |

| • average | 84 m3/s (3,000 cu ft/s)[3] |

| • minimum | 15 m3/s (530 cu ft/s)[3][b] |

| • maximum | 1,018 m3/s (36,000 cu ft/s)[4][c] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | North Muskham |

| • average | 88 m3/s (3,100 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Blithe, Swarbourn, Dove, Derwent, Erewash, Leen, Greet, Idle, Torne |

| • right | Sow, Tame, Mease, Soar, Devon, Eau |

| Progression : River Trent — Humber — North Sea | |

The Trent is the third longest river in the United Kingdom. Its source is in Staffordshire, on the southern edge of Biddulph Moor. It flows through and drains the North Midlands into the Humber Estuary. The river is known for dramatic flooding after storms and spring snowmelt, which in the past often caused the river to change course.

The river passes through Stoke-on-Trent, Stone, Staffordshire, Rugeley, Burton-upon-Trent and Nottingham before joining the River Ouse, Yorkshire at Trent Falls to form the Humber Estuary, which empties into the North Sea between Kingston upon Hull in Yorkshire and Immingham in Lincolnshire. The wide Humber estuary has often been described as the boundary between the Midlands and the north of England.[5][6]

Name

The name "Trent" is possibly from a Romano-British word meaning "strongly flooding". More specifically, the name may be a contraction of two Romano-British words, tros ("over") and hynt ("way").[7] This may indeed indicate a river that is prone to flooding. However, a more likely explanation may be that it was considered to be a river that could be crossed principally by means of fords, i.e. the river flowed over major road routes. This may explain the presence of the Romano-British element rid (cf. Welsh rhyd, "ford") in various place names along the Trent, such as Hill Ridware, as well as the Old English‐derived ford. Another translation is given as "the trespasser", referring to the waters flooding over the land.[8] According to Koch at the University of Wales,[9] the name Trent derives from the Romano-British Trisantona, a Romano-British reflex of the combined elements *tri-sent(o)-on-ā- (through-path-augmentative-feminine-) ‘great thoroughfare’.[9] A traditional but almost certainly wrong opinion is that of Izaak Walton, who states in The Compleat Angler (1653) that the Trent is "... so called from thirty kind of fishes that are found in it, or for that it receiveth thirty lesser rivers."[10]

Course

The Trent rises within the Staffordshire Moorlands district, near the village of Biddulph Moor, from a number of sources including the Trent Head Well. It is then joined by other small streams to form the Head of Trent, which flows south, to the only reservoir along its course at Knypersley Reservoir. Downstream of the reservoir it passes through Stoke-on-Trent and merges with the Lyme, Fowlea and other brooks that drain the six towns of the Staffordshire Potteries to become the River Trent. On the southern fringes of Stoke, it passes through the landscaped parkland of Trentham Gardens.[11]

The river then continues south through the market town of Stone, and after passing the village of Salt, Staffordshire, it reaches Great Haywood, where it is spanned by the 16th-century Essex Bridge, Staffordshire near Shugborough Hall. At this point the River Sow joins it from Stafford. The Trent now flows south-east past the town of Rugeley until it reaches Kings Bromley where it meets the Blithe. After the confluence with the Swarbourn, it passes Alrewas and reaches Wychnor, where it is crossed by the A38 road dual carriageway, which follows the route of the Roman Ryknild Street. The river turns north-east where it is joined by its largest tributary, the River Tame, West Midlands (which is at this point actually the larger, though its earlier length shorter) and immediately afterwards by the River Mease, creating a larger river that now flows through a broad floodplain.

The river continues north-east, passing the village of Walton-on-Trent until it reaches the large town of Burton-upon-Trent. The river in Burton is crossed by a number of bridges including the ornate 19th-century Ferry Bridge, Burton that links Stapenhill to the town.[11] To the north-east of Burton the river is joined by the River Dove, Central England at Newton Solney and enters Derbyshire, before passing between the villages of Willington, Derbyshire and Repton where it turns directly east to reach Swarkestone Bridge. Shortly afterwards, the river becomes the Derbyshire-Leicestershire border, passing the traditional crossing point of King's Mill, Castle Donington, Castle Donington, Weston-on-Trent and Aston-on-Trent.[11]

At Shardlow, where the Trent and Mersey Canal begins, the river also meets the Derwent at Derwent Mouth. After this confluence, the river turns north-east and is joined by the River Soar before reaching the outskirts of Nottingham, where it is joined by the River Erewash near the Attenborough, Nottinghamshire nature reserve and enters Nottinghamshire. As it enters the city, it passes the suburbs of Beeston, Nottinghamshire, Clifton, Nottinghamshire and Wilford; where it is joined by the Leen. On reaching West Bridgford it flows beneath Trent Bridge near the cricket ground of the same name, and beside The City Ground, home of Nottingham Forest F.C., until it reaches Holme Sluices.[11]

Downstream of Nottingham it passes Radcliffe-on-Trent, Stoke Bardolph and Burton Joyce before reaching Gunthorpe, Nottinghamshire with its bridge, lock and weir. The river now flows north-east below the Toot and Trent Hills before reaching Hazelford Ferry, Fiskerton, Nottinghamshire and Farndon, Nottinghamshire. To the north of Farndon, beside the Staythorpe Power Station the river splits, with one arm passing Averham and Kelham, and the other arm, which is navigable, being joined by the Devon before passing through the market town of Newark-on-Trent and beneath the town's castle walls. The two arms recombine at Crankley Point beyond the town, where the river turns due north to pass North Muskham and Holme, Nottinghamshire to reach Cromwell Weir, below which the Trent becomes tidal.[11]

The now tidal river meanders across a wide floodplain, at the edge of which are located riverside villages such as Carlton and Sutton on Trent, Besthorpe and Girton. After passing the site of High Marnham power station, it becomes the approximate boundary between Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire and reaches the only toll bridge along its course at Dunham on Trent. Downstream of Dunham the river passes Church Laneham and reaches Torksey, where it meets the Foss Dyke navigation which connects the Trent to Lincoln and the River Witham. Further north at Littleborough is the site of the Roman town of Segelocum, where a Roman road once crossed the river.[11][12]

It then reaches the town of Gainsborough with its own Trent Bridge. The river frontage in the town is lined with warehouses, that were once used when the town was an inland port, many of which have been renovated for modern use. Downstream of the town the villages are often named in pairs, representing the fact that they were once linked by a river ferry between the two settlements. These villages include West Stockwith and East Stockwith, Owston Ferry and East Ferry, and West Butterwick and East Butterwick.[13][14][15] At West Stockwith the Trent is joined by the Chesterfield Canal and the River Idle and soon after enters Lincolnshire fully, passing to the west of Scunthorpe. The last bridge over the river is at Keadby where it is joined by both the Stainforth and Keadby Canal and the River Torne.[11]

Downstream of Keadby the river progressively widens, passing Amcotts and Flixborough to reach Burton upon Stather and finally Trent Falls. At this point, between Alkborough and Faxfleet the river reaches the boundary with Yorkshire and joins the River Ouse to form the Humber which flows into the North Sea.[11]

Migration of course in historic times

Unusually for an English river, the channel altered significantly during historic times, and has been described as being similar to the Mississippi in this respect, especially in its middle reaches, where there are numerous old meanders and cut-off loops.[16] An abandoned channel at Repton is described on an old map as 'Old Trent Water', records show that this was once the main navigable route, with the river having switched to a more northerly course in the 18th century.[17] Farther downstream at Hemington, archaeologists have found the remains of a medieval bridge across another abandoned channel.[18][19] Researchers using aerial photographs and historical maps have identified many of these palaeochannel features, a well-documented example being the meander cutoff at Sawley.[20][21] The river's propensity to change course is referred to in Shakespeare's play Henry IV, Part 1:

Methinks my moiety, north from Burton here,

In quantity equals not one of yours:

See how this river comes me cranking in,

And cuts me from the best of all my land

A huge half-moon, a monstrous cantle out.

I'll have the current in this place damm'd up;

And here the smug and silver Trent shall run

In a new channel, fair and evenly;

It shall not wind with such a deep indent,

To rob me of so rich a bottom here.— William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1, act 3, scene I[22]

Henry Hotspur's speech complaining about the river has been linked to the meanders near West Burton,[23] however, given the wider context of the scene, in which conspirators propose to divide England into three after a revolt, it is thought that Hotspur's intentions were of a grander design, diverting the river east towards the Wash such that he would benefit from a much larger share of the divided Kingdom. Downstream of Burton upon Trent, the river increasingly trends northwards, cutting off a portion of Nottinghamshire and nearly all of Lincolnshire from his share, north of the Trent.[24][25] The idea for this scene, may have been based on the disagreement regarding a mill weir near Shelford Manor, between local landowners Gilbert Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, and Sir Thomas Stanhope which culminated with a long diversion channel being dug to bypass the mill.[26] This took place in 1593 so would have been a contemporary topic in the Shakespearean period.[24]

Prehistory

During the Pleistocene epoch (1.7 million years ago), the River Trent rose in the Welsh hills and flowed almost east from Nottingham through the present Vale of Belvoir to cut a gap through the limestone ridge at Ancaster and thence to the North Sea.[27] At the end of the Wolstonian Stage (c. 130,000 years ago) a mass of stagnant ice left in the Vale of Belvoir caused the river to divert north along the old Lincoln river, through the Lincoln gap, along what is now the course of the Witham. During a following glaciation (Devensian, 70,000 BC) the ice held back vast areas of water – called Glacial Lake Humber – in the current lower Trent basin. When this retreated, the Trent adopted its current course into the Humber.[28]

Catchment

The Trent basin covers a large part of the Midlands, and includes the majority of the counties of Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and the West Midlands; but also includes parts of Lincolnshire, South Yorkshire, Warwickshire and Rutland. The catchment is located between the drainage basins of the Severn and its tributary the Avon to the south and west, the Weaver to the north-west, the tributaries of the Yorkshire Ouse to the North and the basins of the Welland, Witham and Ancholme to the east.[29][30]

A distinctive feature of the catchment is the marked variation in the topography and character of the landscape, which varies from the upland moorland headwaters of the Dark Peak, where the highest point of the catchment is the Kinder Scout plateau at 634 metres (2,080 ft); through to the intensively farmed and drained flat fenland areas that exist alongside the lower tidal reaches, where ground levels can equal sea level. These lower reaches are protected from tidal flooding by a series of floodbanks and defences.[31][32][33]

Elsewhere there is a distinct contrast between the open limestone areas of the White Peak in the Dove catchment, and the large woodland areas, including Sherwood Forest in the Dukeries area of the Idle catchment, the upland Charnwood Forest, and the National Forest in the Soar and Mease drainage basins respectively.[29]

| Land use[34] |

Land use is predominantly rural, with some three-quarters of the Trent catchment given over to agriculture. This ranges from moorland grazing of sheep in the upland areas, through to improved pasture and mixed farms in the middle reaches, where dairy farming is important. Intensive arable farming of cereals and root vegetables, chiefly potatoes and sugar beet occurs in the lowland areas, such as the Vale of Belvoir and the lower reaches of the Trent, Torne and Idle.[34] Water level management is important in these lowland areas, and the local watercourses are usually maintained by internal drainage boards and their successors, with improved drainage being assisted by the use of pumping stations to lift water into embanked carrier rivers, which subsequently discharge into the Trent.[29]: 29 [35]

The less populous rural areas are offset by a number of large urbanised areas including the conurbations of Stoke-on-Trent, Birmingham and the surrounding Black Country in the West Midlands; and in the East Midlands the major university cities and historical county seats of Leicester, Derby and Nottingham. Together these contain the majority of the 6 million people who live in the catchment.[29]

The majority of these urban areas are in the upper reaches of either the Trent itself, as is the case with Stoke, or its tributaries. For example, Birmingham lies at the upper end of the Tame, and Leicester is located towards the head of the Soar. Whilst this is not unique for an English river, it does mean that there is an ongoing legacy of issues relating to urban runoff, pollution incidents, and effluent dilution from sewage treatment, industry and coal mining. Historically, these issues resulted in a considerable deterioration in the water quality of both the Trent and its tributaries, especially the Tame.[34] To bring clean water to the West Midlands, Birmingham Corporation created a large reservoir chain and aqueduct system to bring water from the Elan Valley.

Geology

Underlying the upper reaches of the Trent, are formations of Millstone Grit and Carboniferous Coal Measures which include layers of sandstones, marls and coal seams. The river crosses a band of Triassic Sherwood sandstone at Sandon, and it meets the same sandstone again as it flows beside Cannock Chase, between Great Haywood and Armitage, there is also another outcrop between Weston-on-Trent and King's Mill.[36][37]

Downstream of Armitage the solid geology is primarily Mercia Mudstones, the course of the river following the arc of these mudstones as they pass through the Midlands all the way to the Humber. The mudstones are not exposed by the bed of the river, as there is a layer of gravels and then alluvium above the bedrock. In places, however the mudstones do form river cliffs, most notably at Gunthorpe and Stoke Lock near Radcliffe on Trent, the village being named after the distinctive red coloured strata.[37][39]

The low range of hills, which have been formed into a steep set of cliffs overlooking the Trent between Scunthorpe and Alkborough are also made up of mudstones, but are of the younger Rhaetic Penarth Group.[36][37]

In the wider catchment the geology is more varied, ranging from the Precambrian rocks of the Charnwood Forest, through to the Jurassic limestone that forms the Lincolnshire Edge and the eastern watershed of the Trent. The most important in terms of the river are the extensive sandstone and limestone aquifers that underlie many of the tributary catchments. These include the Sherwood sandstones that occur beneath much of eastern Nottinghamshire, the Permian Lower Magnesian limestone and the carboniferous limestone in Derbyshire. Not only do these provide baseflows to the major tributaries, the groundwater is an important source for public water supply.[37]

| Gravel Terraces of the River Trent[40] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Age thousand yrs BP |

Stage |

| Eagle Moor | > 400 | Anglian |

| Etwall / Whisby Farm |

297 | Early Wolstonian |

| Egginton / Balderton |

195 | Late Wolstonian |

| Beeston / Scarle |

80 | Devensian |

| Holme Pierrepont | 26 | Devensian |

| Hemington | 10 | Flandrian |

Sand, gravels and alluvium deposits that overlie the mudstone bedrock occur almost along the entire length of the river, and are an important feature of the middle and lower reaches, with the alluvial river silt producing fertile soils that are used for intensive agriculture in the Trent valley. Beneath the alluvium are widespread deposits of sand and gravel, which also occur as gravel terraces considerably above the height of the current river level. There is thought to be a complex succession of at least six separate gravel terrace systems along the river, deposited when a much larger Trent flowed through the existing valley, and along its ancestral routes through the water gaps at Lincoln and Ancaster.[41][42]

This ‘staircase’ of flat topped terraces was created as a result of successive periods of deposition and subsequent down cutting by the river, a product of the meltwater and glacially eroded material produced from ice sheets at the end of glacial periods through the Pleistocene epoch between 450,000 and 12,000 years BP. Contained within these terraces is evidence of the mega fauna that once lived along the river, the bones and teeth of animals such as the woolly mammoth, bison and wolves that existed during colder periods have all been identified.[43] Another notable find in a related terrace system near Derby from a warmer interglacial period, was the Allenton hippopotamus.[41]

The lower sequences of these terraces have been widely quarried for sand and gravel, and the extraction of these minerals continues to be an important industry in the Trent Valley, with some three million tonnes of aggregates being produced each year.[40] Once worked out, the remaining gravel pits which are usually flooded by the relatively high water table have been reused for a wide variety of purposes. These include recreational water activities, and once rehabilitated, as nature reserves and wetlands.[44]

During the end of the last Devensian glacial period the formation of Lake Humber in the lowest reaches of the river, meant that substantial lake bed clays and silts were laid down to create the flat landscape of the Humberhead Levels. These levels extend across the Trent valley, and include the lower reaches of the Eau, Torne and Idle. In some areas, successive layers of peat were built up above the lacustrine deposits during the Holocene period, which created lowland mires such as the Thorne and Hatfield Moors.[45]

Hydrology

The topography, geology and land use of the Trent catchment all have a direct influence on the hydrology of the river. The variation in these factors is also reflected in the contrasting runoff characteristics and subsequent inflows of the principal tributaries. The largest of these is the River Tame, which contributes nearly a quarter of the total flow for the Trent, with the other significant tributaries being the Derwent at 18%, Soar 17%, the Dove 13%, and the Sow 8%.[46]: 36–47 Four of these main tributaries, including the Dove and Derwent which drain the upland Peak District, all join within the middle reaches, giving rise to a comparatively energetic river system for the UK.[47]

Rainfall

Rainfall in the catchment generally follows topography[48] with the highest annual rainfall of 1,450 mm (57 in) and above occurring over the high moorland uplands of the Derwent headwaters to the north and west, with the lowest of 580 mm (23 in), in the lowland areas to the north and east.[49] Rainfall totals in the Tame are not as high as would be expected from the moderate relief, due to the rain shadow effect of the Welsh mountains to the west, reducing amounts to an average of 691 mm (27.2 in) for the tributary basin.[48][50] The average for the whole Trent catchment is 720 mm (28 in) which is significantly lower than the average for United Kingdom at 1,101 mm (43.3 in) and lower than that for England at 828 mm (32.6 in).[51][52][53]

Like other large lowland British rivers, the Trent is vulnerable to long periods of rainfall caused by sluggish low pressure weather systems repeatedly crossing the basin from the Atlantic, especially during the autumn and winter when evaporation is at its lowest. This combination can produce a water-logged catchment that can respond rapidly in terms of runoff, to any additional rainfall. Such conditions occurred in February 1977, with widespread flooding in the lower reaches of the Trent when heavy rain produced a peak flow of nearly 1,000 m3/s (35,000 cu ft/s) at Nottingham. In 2000 similar conditions occurred again, with above average rainfall in the autumn being followed by further rainfall, producing flood conditions in November of that year.[54][55][56]

Another meteorological risk, although one that occurs less often, is that related to the rapid melting of snow lying in the catchment. This can be a result of a sudden rise in temperature after a prolonged cold period, or when combined with extensive rainfall. Many of the largest historical floods were caused by snowmelt, but the last such episode occurred when the bitter winter of 1946-7 was followed by a rapid thaw due to rain in March 1947 and caused severe flooding all along the Trent valley.[54][57]

At the other extreme, extended periods of low rainfall can also cause problems. The lowest flows for the river were recorded during the drought of 1976, following the dry winter of 1975/6. Flows measured at Nottingham were exceptionally low by the end of August, and were given a drought return period of greater than one hundred years.[58]

Discharge

| Discharge of the River Trent at various locations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauging Station |

County | Discharge (average) |

Discharge (maximum) |

Catchment Area |

||||||

| m3/s | cfs | m3/s | cfs | km2 | mi2 | |||||

| Stoke on Trent | 0.6 | 21 | 55 | 1,900 | 53 | 20 | [59][60] | |||

| Great Haywood | 4.4 | 160 | 98 | 3,500 | 325 | 125 | [59][61] | |||

| Yoxall | 12.8 | 450 | 206 | 7,300 | 1,229 | 475 | [59][62] | |||

| Drakelow | 36.1 | 1,270 | 385 | 13,600 | 3,072 | 1,186 | [59][63] | |||

| Shardlow | 51.6 | 1,820 | 480 | 17,000 | 4,400 | 1,700 | [59][64] | |||

| Colwick | 83.8 | 2,960 | 1,018 | 36,000 | 7,486 | 2,890 | [55][59] | |||

| North Muskham | 88.4 | 3,120 | 1,000 | 35,000 | 8,231 | 3,178 | [59][65] | |||

The river's flow is measured at several points along its course, at a number of gauging stations. At Stoke-on-Trent in the upper reaches, the average flow is only 0.6 m3/s (21 cu ft/s), which increases considerably to 4.4 m3/s (160 cu ft/s), at Great Haywood, as it includes the flow of the upper tributaries draining the Potteries conurbation. At Yoxall, the flow increases to 12.8 m3/s (450 cu ft/s) due to the input of larger tributaries including the Sow and Blithe. At Drakelow upstream of Burton the flow increases nearly three-fold to 36.1 m3/s (1,270 cu ft/s), due to the additional inflow from the largest tributary the Tame. At Colwick near Nottingham, the average flow rises to 83.8 m3/s (2,960 cu ft/s), due to the combined inputs of the other major tributaries namely the Dove, Derwent and Soar. The last point of measurement is North Muskham here the average flow is 88.4 m3/s (3,120 cu ft/s), a relatively small increase due to the input of the Devon, and other smaller Nottinghamshire tributaries.[59][66]

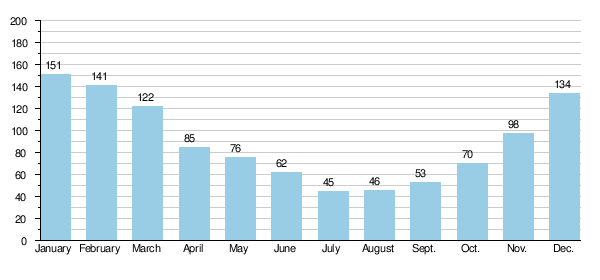

The Trent has marked variations in discharge, with long term average monthly flows at Colwick fluctuating from 45 m3/s (1,600 cu ft/s) in July during the summer, and increasing to 151 m3/s (5,300 cu ft/s) in January.[67][68] During lower flows the Trent and its tributaries are heavily influenced by effluent returns from sewage works, especially the Tame where summer flows can be made up of 90% effluent. For the Trent this proportion is lower, but with nearly half of low flows being made up of these effluent inflows, it is still significant. There are also baseflow contributions from the major aquifers in the catchment.[69][70][71]

- Average monthly flows of Trent in cubic metres per second measured at Colwick (Nottingham).[68]

Sediment

In the lower tidal reaches the Trent has a high sediment load, this fine silt which is also known as ‘warp', was used to improve the soil by a process known as warping, whereby river water was allowed to flood into adjacent fields through a series of warping drains, enabling the silt to settle out across the land. Up to 0.3 metres (1 ft) of deposition could occur in a single season, and depths of 1.5 metres (5 ft) have been accumulated over time at some locations. A number of the smaller Trent tributaries are still named as warping drains, such as Morton warping drain, near Gainsborough.[72]

Warp was also used as a commercial product, after being collected from the river banks at low tide, it was transported along the Chesterfield Canal to Walkeringham where it was dried out and refined to be eventually sold as a silver polish for cutlery manufacturers.[73][74]

Floods

| Largest floods on the River Trent at Nottingham[75] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Date | Level at Trent Bridge | Peak Flow | |||

| m | ft | m3/s | cfs | |||

| 1 | February 1795 | 24.55 | 80.5 | 1,416 | 50,000 | |

| 2 | October 1875 | 24.38 | 80.0 | 1,274 | 45,000 | |

| 3 | March 1947 | 24.30 | 79.7 | 1,107 | 39,100 | |

| 4 | November 1852 | 24.26 | 79.6 | 1,082 | 38,200 | |

| 5 | November 2000 | 23.80 | 78.1 | 1,019 | 36,000 | |

| Normal / Avg flow | 20.7 | 68 | 84 | 3,000 | ||

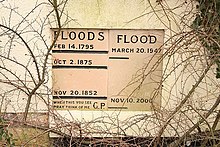

The Trent is widely known for its tendency to cause significant flooding along its course, and there is a well documented flood history extending back for some 900 years. In Nottingham the heights of significant historic floods from 1852 have been carved into a bridge abutment next to Trent Bridge, with flood marks being transferred from the medieval Hethbeth bridge that pre-dated the existing 19th-century crossing. Historic flood levels have also been recorded at Girton and on the churchyard wall at Collingham.[23][75][76]

One of the earliest recorded floods along the Trent was in 1141, and like many other large historical events was caused by the melting of snow following heavy rainfall, it also caused a breach in the outer floodbank at Spalford. Some of the earliest floods can be assessed by using Spalford bank as a substitute measure for the size of a particular flood, as it has been estimated that the bank only failed when flows were greater than 1,000 m3/s (35,000 cu ft/s), the bank was also breached in 1403 and 1795.[77]

Early bridges were vulnerable to floods, and in 1309 many bridges were washed away or damaged by severe winter floods, including Hethbeth Bridge. In 1683 the same bridge was partially destroyed by a flood that also meant the loss of the bridge at Newark. Historical archives often record details of the bridge repairs that followed floods, as the cost of these repairs or pontage had to be raised by borrowing money and charging a local toll.[23][77]

The largest known flood was the Candlemas flood of February 1795, which followed an eight-week period of harsh winter weather, rivers froze which that meant mills were unable to grind corn, and then followed a rapid thaw. Due to the size of the flood and the ice entrained in the flow, nearly every bridge along the Trent was badly damaged or washed away. The bridges at Wolseley, Wychnor and the main span at Swarkestone were all destroyed.[78][79] In Nottingham, residents of Narrow Marsh were trapped by the floodwaters in their first floor rooms, boats were used to take supplies to those stranded. Livestock was badly affected, 72 sheep drowned in Wilford and ten cows were lost in Bridgford.[80] The vulnerable flood bank at Spalford was breached again, floodwaters spreading out across the low-lying land, even reaching the River Witham and flooding Lincoln. Some 20,000 acres (81 km2; 31 sq mi) were flooded for a period of over three weeks.[23][81][82]

A description of the breach was given as follows:

The bank is formed upon a plain of sandy nature, and when it was broken in 1795, the water forced an immense breach, the size of which may be judged from the fact that eighty loads of faggots and upwards of four hundred tons of earth were required to fill up the hole, an operation which took several weeks to complete.

The flood bank was subsequently strengthened and repaired, following further floods during 1824 and 1852.[81]

The principal flood of the 19th century and the second largest recorded, was in October 1875. In Nottingham a cart overturned in the floodwaters near the Wilford Road and six people drowned, dwellings nearby were flooded to a depth of 6 feet (1.8 m). Although not quite as large as 1795 this flood devastated many places along the river, at Burton upon Trent much of the town was inundated, with flooded streets and houses, and dead animals floating past in the flood. Food was scarce, "in one day 10,000 loaves had to be sent into the town and distributed gratuitously to save people from famine".[83] In Newark the water was deep enough to allow four grammar school boys to row across the countryside to Kelham. The flood marks at Girton show that this flood was only 4 inches (100 mm) lower than that of 1795, when the village was flooded to a depth of 3 feet (0.91 m).[23]

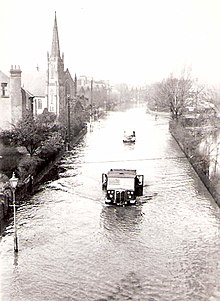

On 17–18 March 1947 the Trent overtopped its banks in Nottingham. Large parts of the city and surrounding areas were flooded with 9,000 properties and nearly a hundred industrial premises affected some to first floor height. The suburbs of Long Eaton, West Bridgford and Beeston all suffered particularly badly.[57][84][85] Two days later, in the lower tidal reaches of the river, the peak of the flood combined with a high spring tide to flood villages and 2,000 properties in Gainsborough. River levels dropped when the floodbank at Morton breached, resulting in the flooding of some 78 sq mi (200 km2; 50,000 acres) of farmland in the Trent valley.[33][85]

Flooding on the Trent can also be caused by the effects of storm surges independently of fluvial flows, a series of which occurred during October and November 1954, resulting in the worse tidal flooding experienced along the lower reaches. These floods revealed the need for a tidal protection scheme, which would cope with the flows experienced in 1947 and the tidal levels from 1954, and subsequently the floodbanks and defences along the lower river were improved to this standard with the works being completed in 1965.[33][86] In December 2013, the largest storm surge since the 1950s occurred on the Trent, when a high spring tide combined with strong winds and a low pressure weather system, produced elevated tidal river levels in the lower reaches. The resulting surge overtopped the flood defences in the area near Keadby and Burringham, flooding 50 properties.[87]

The fifth largest flood recorded at Nottingham occurred in November 2000, with widespread flooding of low-lying land along the Trent valley, including many roads and railways. The flood defences around Nottingham and Burton constructed during the 1950s, following the 1947 event, stopped any major urban flooding, but problems did occur in undefended areas such as Willington and Gunthorpe, and again at Girton where 19 houses were flooded.[56] The flood defences in Nottingham that protect 16,000 homes and those in Burton where they prevent 7,000 properties from flooding were reassessed after this flood, and were subsequently improved between 2006 and 2012.[84][88]