A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

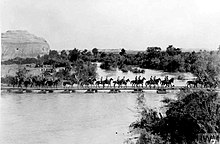

Prisoners captured during the 2nd Transjordan operations marching through Jerusalem May 1918 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

60th (London) Division Anzac Mounted Division Australian Mounted Division Imperial Camel Corps Brigade Two Companies Patiala Infantry |

Fourth Army VIII Corps 3rd Cavalry Division Caucasus Cavalry Brigade 143rd Regiment 3rd and 46th Assault Companies 48th Division 703rd Infantry Battalion a storm battalion, a machine gun company and Austrian artillery | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000 troops | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,784 | |||||||

The Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt,[citation needed] officially known by the British as the Second action of Es Salt [1] and by others as the Second Battle of the Jordan,[2] was fought east of the Jordan River between 30 April and 4 May 1918, during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War. The battle followed the failure of the First Transjordan attack on Amman fought at the beginning April.[1][3] During this second attack across the Jordan River, fighting occurred in three main areas. The first area in the Jordan Valley between Jisr ed Damieh and Umm esh Shert the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) defended their advanced position against an attack by units of the Seventh Army based in the Nablus region of the Judean Hills. The second area on the eastern edge of the Jordan Valley where the Ottoman Army garrisons at Shunet Nimrin and El Haud, on the main road from Ghoraniyeh to Amman were attacked by the 60th (London) Division many of whom had participated in the First Transjordan attack. The third area of fighting occurred after Es Salt was captured by the light horse brigades to the east of the valley in the hills of Moab, when they were strongly counterattacked by Ottoman forces converging on the town from both Amman and Nablus. The strength of these Ottoman counterattacks forced the EEF mounted and infantry forces to withdraw back to the Jordan Valley where they continued the Occupation of the Jordan Valley during the summer until mid September when the Battle of Megiddo began.

In the weeks following the unsuccessful First Transjordan attack on Amman and the First Battle of Amman, German and Ottoman Empire reinforcements strengthened the defences at Shunet Nimrin, while moving their Amman army headquarters moved forward to Es Salt. Just a few weeks later at the end of April, the Desert Mounted Corps again supported by the 60th (London) Division were ordered to attack the recently entrenched German and Ottoman garrisons at Shunet Nimrin and advance to Es Salt with a view to capturing Amman. Although Es Salt was captured, the attack failed despite the best efforts of the British infantry's frontal attack on Shunet Nimrin and the determined light horse and mounted rifle defences of the northern flank in the Jordan Valley. However, the mounted yeomanry attack on the rear of Shunet Nimrin failed to develop and the infantry attack from the valley could not dislodge the determined Ottoman defenders at Shunet Nimrin. By the fourth day of battle, the strength and determination of the entrenched German and Ottoman defenders at Shunet Nimrin, combined with the strength of attacks in the valley and from Amman in the hills, threatened the capture of one mounted yeomanry and five light horse brigades in the hills, defending Es Salt and attacking the rear of the Shunet Nimrin position, forcing a retreat back to the Jordan Valley.

Background

The German and Ottoman forces won victories at the first and second battles of Gaza in March and April 1917. But from the last day of October 1917 to the end of the year, the German, Austrian and Ottoman Empires endured a series of humiliating defeats in the Levant, culminating in the loss of Jerusalem and a large part of southern Palestine to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). From just north of the Ottoman frontier with Egypt they were defeated at Gaza, at Sheria and at Beersheba, resulting in a retreat to Jaffa and the Judean Hills.[4] The Ottoman Army was again forced to retreat, this time from Capture of Jericho by General Edmund Allenby's force in February 1918.[5]

In late March and early April, German and Ottoman forces defeated Major Generals John Shea and Edward Chaytor's force at the first Transjordan attack. The Ottoman Fourth Army's VIII Corps' 48th Division with the 3rd and 46th Assault Companies and the German 703rd Infantry Battalion successfully defended Amman against the attack by the Anzac Mounted Division with the 4th (Australian and New Zealand) Battalion Imperial Camel Corps Brigade,[6][7] reinforced by infantry from the 181st Brigade, 60th (London) Division.[8][9]

The objective of the First Transjordan operations had been to disable the Hejaz Railway near Amman by demolishing viaducts and tunnels. As Shea's force moved forward, Shunet Nimrin on the main road from Ghoraniyeh to Es Salt and Amman and the town of Es Salt were captured by the infantry and mounted force. While Es Salt was garrisoned by infantry from the 60th (London) Division, two brigades of Chaytor's Anzac Mounted Division (later reinforced by infantry and artillery) continued on to Amman. The operations had only been partly successful by the time large numbers of German and Ottoman reinforcements forced a withdrawal back to the Jordan. The only territorial gains remaining in the EEF's control were the Jordan River crossings at Ghoraniyeh and Makhadet Hajlah, where pontoon bridges had been built and a bridgehead established on the eastern bank.[10][11][12] With their lines of communication seriously threatened by attacks in the Jordan Valley, Shea's and Chaytor's forces withdrew to the Jordan Valley, by 2 April 1918, maintaining the captured bridgeheads.[13]

On 21 March, Erich Ludendorff launched the German spring offensive on the Western Front, coinciding with the start of the first Transjordan attack; overnight the Palestine theatre of war went from the British government's first priority to a "side show."[14] Because of the threat to Allied armies in Europe, 24 battalions – 60,000 mostly-British soldiers – were sent to Europe as reinforcements. They were replaced by Indian infantry and cavalry from the British Indian Army.[2][15][16]

The large troop movements these withdrawals and reinforcements required caused a substantial reorganisation of the EEF.[17] Until September, when Allenby's force would be completely reformed and retrained, it would not be in a position to successfully attack both the Transjordan on the right and the Plain of Sharon on the left as well as continuing to hold the centre in the Judean Hills. In the meantime, it seemed essential to occupy the Transjordan to establish closer ties with Britain's important Arab ally, Feisal and the Hejaz Arabs. Until direct contact was made, Allenby could not completely support this force and he knew that if Feisal was defeated, German and Ottoman forces could turn the whole length of the EEF's right flank. This would make their hard-won positions shaky all the way to Jerusalem, and could result in a humiliating withdrawal, possibly to Egypt. Apart from the extremely important military ramifications of such a loss of captured territory, the political fallout could include a negative effect on the Egyptian population, upon whose cooperation the British war effort relied heavily.[18] Allenby hoped that a series of attacks into the hills of Moab could turn Ottoman attention away from the Plain of Sharon, north of Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast, to the important railway junction at Daraa which, if captured by T.E. Lawrence and Feisal, would seriously dislocate the Ottoman railway and lines of communication in Palestine.[17][19]

Prelude

After the withdrawal from Amman, the British infantry continued operations in the Judean Hills, launching unsuccessful attacks towards Tulkarem between 9 and 11 April with the aim of threatening Nablus.[20] Also on 11 April, the Ottoman 48th Infantry Division, reinforced by eight squadrons and 13 battalions, unsuccessfully attacked the Anzac Mounted Division and the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade, supported in turn by the 10th Heavy Battery and 301st Brigade Royal Field Artillery, in and near the Jordan Valley, at the Ghoraniyeh and Aujah bridgeheads and on Mussallabeh hill.[21][22][23] Between 15 and 17 April, Allenby's Hejaz Arab force attacked Ma'an with partially successful results.[24]

To support the Hejaz Arab attacks at Ma'an, Lieutenant-General Philip W. Chetwode tried to divert German and Ottoman attention away from them, encourage further operations against Amman, and attract more German and Ottoman reinforcements to Shunet Nimrin instead. He ordered Chaytor to lead an attack on 18 April against the strongly entrenched Shunet Nimrin garrison of 8,000 with a force that included an attached infantry brigade the 180th and the Anzac Mounted Division, supported by a heavy and siege artillery batteries. Also, two battalions from the 20th Indian Brigade held the Ghoraniyeh bridgehead.[25] Then on 20 April Allenby ordered Lieutenant-General Harry Chauvel of the Desert Mounted Corps to destroy the force at Shunet Nirmin and capture Es Salt with two mounted divisions and an infantry division.[26][27][28][29]

During the first Transjordan attack on Amman, the high country had still been in the grip of the wintry wet season, which badly degraded roads and tracks in the area making the movements of large military units extremely difficult. Just a few weeks later, with the rainy season over, movement was considerably easier, but the main road via Shunet Nimrin was heavily entrenched by the Ottoman army and could no longer be used to move on Es Salt; Chauvel's mounted brigades were forced to rely on secondary roads and tracks.[30]

Plans

Allenby's ambitious overall concept was to capture a great triangle of land with its tip at Amman, its northern line running from Amman to Jisr ed Damieh on the Jordan River and its southern line running from Amman to the north shore of the Dead Sea.[17][31] He ordered Chauvel to make bold and rapid marches, in an attempt to develop the attack into the total overthrow of the whole of the German and Ottoman forces. Allenby confirmed, "As soon as your operations have gained the front Amman–Es Salt, you will at once prepare for operations northward, with a view to advancing rapidly on Daraa." Chauvel's instructions included the optimistic assessment that it was unlikely that the defenders would risk withdrawing troops from the main battlefront in the Judean Hills to reinforce Shunet Nimrin.[31][32]

During the first Transjordan attack reinforcements from Nablus in the Judean Hills crossed the Jordan River to attack the northern flank, threatening the supply lines of Shea's force.[33][34] This area, together with the infantry frontal attack on Shunet Nimrin, saw the first stage of the second operation; capturing Jisr ed Damieh, Es Salt and Madaba would allow a base for advances to the Hejaz railway at Amman and the railway junction at Daraa.[31][32]

The Jisr ed Damieh crossing was on the main Ottoman lines of communication from the Ottoman Eighth Army headquarters at Tulkarem to the Ottoman Seventh Army headquarters at Nablus via the Wadi Fara and to the north from Beisan and Nazareth. The German and Ottoman forces at all these places could quickly and easily move reinforcements and supplies to the Fourth Army at Es Salt and on to Amman by crossing the Jordan River at this ford.[35][36]

Chauvel planned to control this strategically vital crossing and secure the left flank by first moving the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade from the Auja bridgehead to take control of the fords south of Jisr ed Damieh from the western side of the river. Second, the 4th Light Horse Brigade, Australian Mounted Division, would advance up the valley to take control of the road from Jisr ed Damieh to Es Salt. With this important flank secure, the 60th (London) Division under Shea was to make a frontal attack on Shunet Nimrin from the Jordan Valley while the Anzac and Australian Mounted Divisions commanded by Chaytor and Henry West Hodgson moved north up the Jordan Valley to capture the Jisr ed Damieh. After he left one brigade at Jisr ed Damieh as flank guard, covered from the west bank by the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade, the remaining brigades would move up the road to Es Salt, capture the village and launch a second attack on Shunet Nimrin from the rear.[37][38][39] One brigade of the Anzac Mounted Division was attached to the Australian Mounted Division, while the remainder of the Anzac Mounted Division formed the reserve.[39]

Problems

Planning for both the first and second Transjordan operations optimistically assumed Ottoman reinforcements would not leave the Judean Hills and cross the river, which would have disastrous effects on the operations.[31][32][40][Note 1] Neither Chauvel, nor Shea the commander of the 60th (London) Division, were keen on the second Transjordan operations.[29][41][Note 2]

Chauvel considered the operation impracticable, believing he lacked sufficient striking power and supply capacity.[42] On 26 April Chauvel explained his supply problems in detail to General Headquarters (GHQ) and asked to postpone operations against Amman and Jisr ed Damieh. In reply GHQ said they would take Chauvel's points into account before ordering any further advance, but also that the first stage, clearing the country up to the Madaba – Es Salt – Jisr ed Damieh line, would go ahead.[41]

The men of the 60th (London) Division had suffered greatly only a few weeks before during the first Transjordan operations, particularly during the attack on Amman, and had had little time to recover between attacks. Further, tackling the 5,000 strongly entrenched Ottomans around Shunet Nimrin, put on the alert by Chetwode's attack on 18 April, would be a chilling prospect.[29][41]

Chetwode later said that the first and second Transjordan attacks were "the stupidest things he ever did."[17] Chauvel had no confidence in the promised Arab support Allenby relied on. The attack on Shunet Nirmin relied heavily on the Beni Sakhr's ability to capture and hold Ain es Sir to cut the German and Ottoman supply line to Shunet Nimrin.[37][42]

Beni Sakhr

I have had some local fights; but I am no longer pushing North. The Arabs are doing well, East of Jordan; and I have been helping them by forcing the Turks to keep a big force of all arms opposite my bridgehead on the Jordan. I hope soon to send a considerable mounted force across the Jordan, gain permanent touch with the Arabs and deny to the Turks the grain harvest of the Salt–Madaba area. They depend largely on this grain supply.

Allenby report to Henry Wilson, CIGS 20 April 1918[43]

Envoys from the Bedouin Beni Sakhr tribe, camped on the plateau about 20 miles (32 km) east of Ghoraniyeh, informed Allenby that they had 7,000 men concentrated at Madaba who could cooperate in a British advance on the east bank of the Jordan River. But due to supplies they would need to disperse to distant camping grounds by the first week in May. They assured Allenby that as soon as the Hejaz Arabs arrived, they would join them.[38][44]

The attacks on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt were planned for about the middle of May, after the promised Indian cavalry divisions arrived.[45] But Allenby accepted the Beni Sakhr offer and brought the date for operations forward by two weeks, in the hope that the 7,000 Beni Sakhr would make up for the Indian cavalry. The Beni Sakhr offer to join the Hejaz Arabs was also enticing because these two groups together might be able to hold Es Salt and Shunet Nimrin permanently, making it unnecessary for Allenby's force to garrison the Jordan Valley over the summer period.[27][45]

The change in timing rushed preparations for the operations, which were hasty and imperfect as a result.[46] The original instructions for the second Transjordan operations contained only a general statement that considerable help might be counted on from the Beni Sakhr and that Chauvel should keep in close touch with them.[32] GHQ had no clear idea of the capabilities of the Beni Sakhr, but GHQ fitted them into Chauvel's battle and Allenby ordered Chauvel to attack on 30 April. All this happened without asking the opinion of either T. E. Lawrence or Captain Hubert Young, Lawrence's liaison officer with the Beni Sakhr, who was aware that the leader of the Arabs around Madaba was both perplexed and frightened by GHQ's reaction to his envoys.[32] Lawrence was in Jerusalem during the Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt operations and claimed no knowledge of the Beni Sakhr, or their leader.[47]

British Empire aircraft flying over the plains around Madaba saw large numbers of Bedouin ploughing their fields and grazing their animals, until they decamped across the Hejaz railway when attack on Shunet Nimrin began.[48]

Defending forces

At this time the headquarters of the German commander in chief of the Ottoman armies in Palestine, Otto Liman von Sanders, was at Nazareth. The headquarters of the Ottoman Seventh and Eighth Armies remained at Nablus and Tulkarem.[49][50][Note 3] The Ottoman Fourth Army's headquarters moved forward from Amman to Es Salt after the first Transjordan attack. The Fourth Army headquarters was defended by three companies.[31]

In the hills of Moab beyond the Jordan, Ottoman forces were at least two thousand stronger than British GHQ estimated.[51] Amman was held by two or three battalions, possibly the German 146th Regiment's 3/32nd, 1/58th, 1/150th Battalions.[dubious – discuss][31][52] a Composite Division, a German infantry company and an Austrian artillery battery.[52][53] To the east of the Jordan River the main Ottoman force of 5,000 held Shunet Nimrin with 1,000 defending Es Salt.[54] The Ottoman VIII Corps, Fourth Army, commanded by Ali Fuad Bey defended Shunet Nimrin, comprising the 48th Division, a Composite Division (made up of a variety of known units), a German infantry company and an Austrian artillery battery.[52][53]

After the first Transjordan attack on Amman, the 3rd Cavalry Division, the Caucasus Cavalry Brigade and several German infantry units which moved to the northern Jordan Valley had reinforced the Fourth Army under Jemal Pasha. These infantry units were based mainly on the west bank near Mafid Jozele where a pontoon bridge had been built. The Ottoman 24th Infantry Division, less one regiment and artillery, was also in the area and detachments patrolled the east bank to the south to maintain touch with Fourth Army patrols from Es Salt.[31][42][55] Also part of their force was a Circassian Cavalry Regiment of Arab and Circassian tribesmen.[52]

After the attack began Liman von Sanders requested reinforcements from the commander at Damascus who was to send all available troops by rail to Daraa. Two German infantry companies moving westward by rail from Daraa were ordered to de-train and join the Ottoman 24th Infantry Division. At Shunet Nimrin the VIII Corps held their ground while troops moved against the left flank of the Desert Mounted Corps.[50][56]

The Ottoman Seventh Army formed a new provisional combat detachment designed to counter-attack into the British flank.[57][Note 4] On 1 May the Ottoman troops which pushed in the 4th Light Horse Brigade's flank guard near Jisr ed Damieh, were the Ottoman 3rd Cavalry Division and part of an infantry division (probably the VIII Corps' 48th Division) part of whom continued on up the road to attack Es Salt.[58]

Attacking force

While the remainder of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force held the front line from the Mediterranean Sea to the Dead Sea and garrisoned the captured territories, Chauvel the commander of Desert Mounted Corps, replaced Chetwode, who was the commander of the XX Corps, as commander of the Jordan Valley. Chauvel took command of the Jordan Valley, as well as responsibility for second Transjordan operations.[19][59]

Chauvel's force was one mounted division stronger than the one that attacked Amman the month before, consisting of –

- the 60th (London) Division, an infantry division, commanded by Major General John Shea (less the 181st Brigade in reserve in the Judean Hills on the XX Corps front)

- the 20th Indian Brigade commanded by Brigadier General E. R. B. Murray, formed mostly by infantry from the Indian princely states,

- the Anzac Mounted Division commanded by Chaytor

- the Australian Mounted Division commanded by Major General H. W. Hodgson.[46][60]

The following units were attached to the Australian Mounted Division for their attack on Es Salt: the 1st Light Horse Brigade from the Anzac Mounted Division, the Mysore and Hyderabad lancers, from the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade, the Dorset and Middlesex Yeomanry from the 6th, the 8th Mounted Brigades, the Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Artillery Battery and the 12th Light Armoured Motor Battery.[46][60][Note 5]

In addition to this attacking force, stationed on the west bank of the Jordan River to guard the left flank were the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade with the 22nd Mounted Brigade.[46][60][Note 6] The XIX Brigade RHA comprising the 1/1st Nottinghamshire Royal Horse Artillery and "1/A" and "1/B" Batteries, Honourable Artillery Company,[61] were attached to the 4th Light Horse Brigade to support its defence of the northern flank in the Jordan Valley.[62][Note 7]

After their return from the first Transjordan raid, the Anzac Mounted Division remained in the Jordan Valley; camped near Jericho and were involved in the demonstration against Shunet Nimrin on 18 April. The Australian Mounted Division, which had been in rest camp near Deir el Belah from 1 January to April, moved via Gaza and Mejdel to Deiran 3 miles (4.8 km) from Jaffa in preparation to take part in the attacks northwards towards Tulkarem, known by the Ottomans as the action of Berukin from 9 to 11 April, however the engagement did not develop to a point where the mounted division could be deployed. [Note 8] During this time the Australian Mounted Division remained close to the front line, able to hear heavy bombardments from time to time both day and night and see increased aircraft operations.[63][64] After training and refitting at Deiran, on 23 April the division marched via Jerusalem and the next day down 1,500 feet (460 m) to the Jordan Valley to join the Anzac Mounted Division near Jericho.[65]

Then into Jerusalem by the Jaffa gate and right through the centre of the old city, with ancient buildings close on either side. Out through another old gate in the city wall, past the garden of Gethsemane with its fir trees, and the Mount of Olives ... Our ride through the Holy City was a tremendous thrill. The whole Division took about three hours to file slowly through the narrow streets, two horsemen abreast. It was an impressive and memorable occasion – over 6,000 mounted troops with their Machine Gun Sections, Engineers, Ambulances, supplies and transport, complete in every detail. Tough, efficient, splendidly equipped, battle-hardened, well led and well trained soldiers, a magnificent body of men and horses.

— Patrick M. Hamilton, 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance[66]

The Australian Mounted Division crossed the Jordan River at Ghoraniyeh on a pontoon bridge just wide enough for one vehicle or two horses abreast.[67][68] Then, led by the 4th Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General William Grant) the division advanced rapidly northwards to Jisr ed Damieh; the 3rd Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General Lachlan Wilson) continuing on to ride hard from Jisr ed Damieh to capture Es Salt. Meanwhile, the 4th Light Horse Brigade supported by at least two Royal Horse Artillery batteries took up their position of flank guard astride the Jisr ed Damieh to Es Salt road facing north-west opposite a strong German and Ottoman position holding the bridge over the Jordan River.[Note 9] The 5th Mounted Brigade (Brigadier General Philip Kelly) followed by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General Granville Ryrie) moved towards Es Salt along the Umm esh Shert track.[67] They were followed later by the 1st Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General Charles Cox) which remained across the track as guard for a time.[69][Note 10]

The force attacking Shunet Nimrin from the west was made up of the 179th and 180th Brigades (commanded by Brigadiers General FitzJ. M. Edwards and C. F. Watson) of the 60th (London) Division with their 301st and 302nd Brigades Royal Field Artillery, the IX Mountain Artillery Brigade (less one battery with the Australian Mounted Division) and the 91st Heavy Battery with the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiment, New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, covering the right flank.[53][70][71][Note 11] The Anzac Mounted Division had one regiment from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade covering the right flank of the 60th (London) Division, and the 7th Light Horse Regiment, from the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, attached to the 60th Division. Their 1st Light Horse Brigade was attached to the Australian Mounted Division, and the remainder formed a reserve.[72]

Air support

Bombing raids on the German and Ottoman rear were carried out by No. 142 Squadron RAF (Martinsyde G.100s and Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.12a's) while roaming destroyer patrols over the whole front were carried out by No. 111 Squadron RAF (Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5s). Aerial reconnaissance patrol aircraft flew as far as 60 miles (97 km) behind enemy lines locating several suspected Ottoman headquarters, new aerodromes, important railway centres, new railway and road works, dumps, parks of transport and troop camps. Strategic reconnaissance missions which had been carried out before the first Transjordan attack, were repeated by No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps; during 20 photography patrols over the eastern Jordan, 609 photographs were taken. The new information about all local roads, tracks and caravan routes in the Amman and Es Salt district was incorporated into revised maps.[73]

To stop the possibility of repetitions of attacks by German and Ottoman aircraft during the concentration of Chauvel's force, as had occurred prior to the first Transjordan operations, patrols were increased over the area during daylight hours.[74] These appear to have been completely successful as despite the size of the force, Liman von Sanders claims, "so secretly and ably had their preparations been carried out that even the most important were hidden from our aviators and from ground observation".[75]

Battle

30 April

Infantry in the Jordan Valley attack Shunet Nimrin

From the Ghoraniyeh crossing, a metaled road extended 6 miles (9.7 km) across the Jordan Valley to the Shunet Nimrin defile at the foot of the hills of Moab.[76][77] Here at Shunet Nimrin opposite the Ghoraniyeh bridgehead and crossing, the Ottoman Fourth Army's VIII Corps was strongly entrenched in positions, which controlled the main sealed road from Jericho to Es Salt and Amman and the Wadi Arseniyat (Abu Turra) track.[78][79][Note 12] The Ottoman Corps' main entrenchments ran north and south just to the west of Shunet Nimrin with the deep gorge of the Wadi Kerfrein forming their left flank while their right was thrown back in a half circle across the Wadi Arseniyat track to El Haud. Both flanks were protected by cavalry and the garrison was ordered to hold the strongly entrenched position of Shunet Nimrin at all costs. Their lines of communication to Amman ran through Es Salt and along the Wady Es Sir via the village of Ain es Sir.[50][74][78]

Chauvel's plan was to envelop and capture the Shunet Nimrin garrison and cut their lines of communication; firstly by the capture of Es Salt by light horse who would block the main road to Amman and secondly by the Beni Sakhr who were to capture Ain es Sir and block that track. With Shunet Nimrin isolated there was every reason to believe a frontal attack by British infantry from the Jordan Valley, with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade covering their right flank, would succeed.[78][80][Note 13]

The infantry attack was launched in bright moonlight at the same time as the Australian light horse galloped north along the eastern bank of the Jordan River towards Jisr ed Damieh.[81] By 02:15 leading infantry battalions were deployed opposite their first objectives which were 500–700 yards (460–640 m) away.[67] The infantry captured the advanced German and Ottoman outposts line in the first rush but the second line of solid entrenched works were strongly defended and by mid morning cross-fire from concealed machine guns had brought the advance to a standstill.[53][81] As soon as the 179th Brigade on the left emerged from cover to attack El Haud they were seen in the moonlight and fired on by these machine guns. Some slight progress was made by the 2/14th Battalion, London Regiment, 179th Brigade which captured 118 prisoners but progress became impossible due to heavy and accurate machine gun fire. Before dawn the 180th Brigade on the right made three attempts to gain two narrow paths but was fired on by machine guns and failed to reach their objective; the 2/20th Battalion, London Regiment managed to decisively defeat a reserve company killing 40 German or Ottoman soldiers and capturing 100 prisoners.[82]

Without the advantage of good observation the protracted artillery fire-fight which developed was lost by the British gunners who had problems getting ammunition forward over the fire-swept lower ground and at critical moments the infantry lacked much needed fire support owing to great difficulties in communicating with the artillery. It was eventually decided to stop the attack and to resume it the next morning.[81] After sunset the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade withdrew into reserve by the Ghoraniyeh bridge leaving the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment with the 180th Brigade.[70]

The first infantry casualties arrived from Shunet Nimrin at the divisional receiving station three hours after the fighting began: two hours later they were at the corps main dressing station and later that day they reached the casualty clearing station at Jerusalem. By evening 409 cases had been admitted to the Anzac Mounted Division receiving station and evacuation was going on smoothly. To keep the station clear of casualties, on the following day the motor lorries, general service wagons and some of the light motor ambulances that had been brought inside the bridgehead were used to supplement the heavy cars taking the wounded back for treatment.[83]

Light horse advance up Jordan River's east bank

The Australian Mounted Division with the 1st Light Horse Brigade, the Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Artillery Battery and the 12th Light Armoured Motor Battery (LAMB) attached, crossed the Ghoraniyeh bridge at 04:00 on the morning of 30 April.[72] The 4th Light Horse Brigade with the Australian Mounted Division's "A" and "B" Batteries HAC and the Nottinghamshire Battery RHA attached led the 3rd Light Horse Brigade 16 miles (26 km) north from the Ghoraniyeh bridgehead up the flat eastern bank of the Jordan towards Jisr ed Damieh.[39][84][85]

The 4th Light Horse Brigade was to act as the northern flank guard to prevent German and Ottoman forces moving from the east to the west bank of the Jordan River, while the 3rd Light Horse Brigade with six guns of the Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Artillery Battery advanced up the road from Jisr ed Damieh to capture Es Salt.[85][86] If the 4th Light Horse Brigade were unable to capture the crossing they were to be deployed in such a way as cover and block this important route from Nablus and Beisan to Es Salt.[78][85][87][Note 14] At the same time as the two light horse brigades moved north on the eastern bank of the Jordan River, the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade was to move up the western bank to cover the Umm esh Shert crossing south of Jisr ed Damieh. The 1st Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades, the Australian Mounted Division headquarters and two mountain batteries were to ride up the Umm esh Shert track to Es Salt.[72][88]

The safety of galloping horses in open formation under shell-fire was never more strikingly demonstrated. In the long gallop only six men were killed and 17 wounded.

Henry Gullett[89]

For 15 miles (24 km) from the Wadi Nimrin to the Jisr ed Damieh the terrain on the eastern side of the Jordan river was favourable for rapid movement by the mounted force; the Jordan river valley from the Wady\i Nimrin across the Wadi Arseniyat (which flows into the Jordan) to Umm esh Shert the flats were about 5 miles (8.0 km) wide but further north narrowed between foot-hills on the east and mud-hills along the river. Beyond Umm esh Shert the height of Red Hill jutted out from beside the Jordan to dominate the valley with encroaching foot-hills to the east. Ottoman fire was expected from guns attacking the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade on the west side of the river but Grant (commander of 4th Light Horse Brigade) relied on speed to get past machine gun and rifle fire from the foothills on his right and on his left from Red Hill and the mud-hills.[90] Firing from Red Hill and the western side of the river sent shrapnel bursting over the scattered squadrons whose pace was increased to a gallop.[89]

Posts held by the Ottoman cavalry formed a defensive line extending across the valley from Umm esh Shert.[91] This defensive line formed a line of communications, linking the German and Ottoman forces in the Fourth Army west of the Jordan River with the VIII Corps defending Shunet Nimrin. These defensive posts were attacked by the 4th Light Horse Brigade mounted, and driven back towards Mafid Jozele 4.5 miles (7.2 km) north of Umm esh Shert.[51][91] While the 3rd and 4th Light Horse Brigades continued northwards the 1st Light Horse Regiment (1st Light Horse Brigade) was ordered to attack the German and Ottoman force on Red Hill about 6,000 yards (5,500 m) north-east of Umm esh Shert.[92]

As the light horse screens advanced the mud-hills became more prominent, the passages deeper than they were further south and the two brigades were soon confined to a few broad winding wadi passages studded with large bushes. Ottoman resistance quickly developed along their whole front and the light horsemen were checked and held while still 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Jisr ed Damieh at 05:30 on 30 April.[93][94][Note 15]

A squadron of the 11th Light Horse Regiment was sent forward at 08:00 to capture the Jisr ed Damieh bridgehead, but could not get closer than 2,000 yards (1,800 m) and even though the squadron was reinforced, they were attacked across the Jisr ed Damieh bridge by German and Ottoman infantry supported by a squadron of cavalry which forced the Australians to withdraw about 1 mile (1.6 km) eastwards. German and Ottoman forces then secured the bridge and German and Ottoman reinforcements were able to cross over the Jordan River as the bridge was no longer under observation nor threat from British artillery. Later two squadrons of the 12th Light Horse Regiment attempted to push along the Es Salt track onto the Jisr ed Damieh bridge but were unsuccessful. Meanwhile, a light horse patrol pushed northwards and at 08:00 reached Nahr ez Zerka (Wady Yabbok) about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north of Jisr ed Damieh.[94][95][96]

The 4th Light Horse Brigade initially took up a line 8 miles (13 km) long with both flanks exposed facing north-west about 2,000 yards (1,800 m) west of the foothills covering the Jisr el Damieh to Es Salt track. This line stretched from the Nahr el Zerka to a point about .5 miles (0.80 km) south of the Es Salt track. They were supported by the Australian Mounted Division's XIX Brigade RHA which were pushed forward to cover the bridge at Jisr ed Demieh and the track leading down from Nablus on the west side. These batteries were ineffective as the range was extreme, the targets indefinite and the defensive fire power of the light 13-pounder guns small.[61][89][94]

About midday, the 1st Light Horse Regiment captured Red Hill and took over the prominent position after some intense fighting while its former German and Ottoman garrison retired across the Jordan to where there were already greatly superior enemy reinforcements. An attempt to approach these forces between Red Hill and Mafid Jozele by the light horse was stopped by heavy machine gun fire from the large force. At 15:00, the 1st Light Horse Brigade was directed by Desert Mounted Corps to move up the Umm esh Shert track to Es Salt, leaving one squadron on Red Hill.[94][95][96]

There was a gap of 3–4 miles (4.8–6.4 km) between the 4th Light Horse Brigade's left, which was held by the 11th Light Horse Regiment, and the squadron of 1st Light Horse Regiment on Red Hill supported by two squadrons deployed at the base of the hill.[97][98] Two armoured cars of the 12th Light Armoured Motor Battery were ordered by Grant to watch the gap on the left flank between Red Hill and Jisr ed Damieh. One of those cars was fairly quickly put out of action by a direct hit from a German or Ottoman shell (or was abandoned after being stuck in a deep rut), but the other remained in action until the following day when it was forced to retire, owing to casualties and lack of ammunition.[99][100] Chauvel came to inspect the deployments about 16:00 in the afternoon, when Grant (commander of 4th Light Horse Brigade) explained his difficulties, and requested another regiment to reinforce Red Hill. Chauvel had already sanctioned the move by the 1st Light Horse Brigade to Es Salt, leaving the squadron on Red Hill with four machine guns under Grant's orders and had withdrawn the 2nd Light Horse Brigade from supporting infantry in the 60th (London) Division, ordering it to follow the 1st Light Horse to Es Salt. He therefore had no spare troops and directed Grant to withdraw from Nahr ez Zerka but to continue to hold the Nablus to Es Salt road where it entered the hills towards Es Salt.[97]

After Chauvel returned to his headquarters, Grant was warned by Brigadier General Richard Howard-Vyse the Brigadier General General Staff head of G Branch (BGGS) to deploy his artillery batteries so that if necessary, they could be certain of being able to safely withdraw.[101]

On their way to Jisr ed Damieh, the 3rd and 4th Light Horse Field Ambulances were heavily shelled while following in the rear of their brigades.[Note 16] An advanced dressing station was formed by the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance about 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the Umm esh Shert track, to serve both 3rd and 4th Light Horse Brigades. After sending its wheeled transport back to Ghoraniyeh bridgehead, the 3rd Light Horse Field Ambulance with their camels and horses made the journey on foot through the hills up the Jisr ed Damieh to Es Salt road, which went along the edges of very steep and in parts very slippery cliffs. At 20:00 they halted for the night in a wadi 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Es Salt.[69]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Second_Transjordan_attack_on_Shunet_Nimrin_and_Es_Salt_(1918)Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk