A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

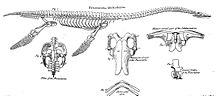

This timeline of plesiosaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, taxonomic revisions, and cultural portrayals of plesiosaurs, an order of marine reptiles that flourished during the Mesozoic Era. The first scientifically documented plesiosaur fossils were discovered during the early 19th century by Mary Anning.[1] Plesiosaurs were actually discovered and described before dinosaurs.[2] They were also among the first animals to be featured in artistic reconstructions of the ancient world, and therefore among the earliest prehistoric creatures to attract the attention of the lay public.[3] Plesiosaurs were originally thought to be a kind of primitive transitional form between marine life and terrestrial reptiles. However, now plesiosaurs are recognized as highly derived marine reptiles descended from terrestrial ancestors.[4]

Early researchers thought that plesiosaurs laid eggs like most reptiles. They commonly imagined plesiosaurs crawling up beaches and burying eggs like turtles. However, later opinion shifted towards the idea that plesiosaurs gave live birth and never went on dry land.[5] Plesiosaur locomotion has been a source of continuous controversy among paleontologists.[6] The earliest speculations on the subject during the 19th century saw plesiosaur swimming as analogous to the paddling of modern sea turtles. During the 1920s opinion shifted to the idea that plesiosaurs swam with a rowing motion.[7] However, a paper published in 1975 that once more found support for sea turtle-like swimming in plesiosaurs.[8] This conclusion reignited the controversy regarding plesiosaur locomotion through the late 20th century.[9] In 2011, F. Robin O'Keefe and Luis M. Chiappe concluded the debate on plesiosaur reproduction, reporting the discovery of a gravid female plesiosaur with a single large embryo preserved inside her.[10]

Prescientific

Associated remains of plesiosaurs and animals like the diving bird Hesperornis or the pterosaur Pteranodon may have inspired legends about conflict between Thunder Birds and Water Monsters told by the Native Americans of Kansas and Nebraska.[11]

18th century

- William Stukeley described the first partial skeleton of a plesiosaur, brought to his attention by the great-grandfather of Charles Darwin, Robert Darwin of Elston.[12]

19th century

1810s

- Mary Anning discovered some plesiosaur fossils in England.[1]

1820s

- Henry De la Beche and William Conybeare are the first to name a plesiosaurian species: Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus.[13]

- Parkinson coined the name Plesiosaurus priscus for some of the remains used by de la Beche and Conybeare as the basis for Plesiosaurus. This species is currently regarded as of dubious taxonomic value.[14]

December

- Mary Anning discovered a nearly complete Plesiosaurus skeleton near Lyme Regis. This specimen would later be catalogued as BMNH 22656.[15]

c. December

- Around the same time as the discovery of BMNH 22656, another Plesiosaurus specimen was discovered at the same site. The specimen was donated to the Oxford University museum and is probably the specimen known today as OXFUM J.10304.[16]

- Conybeare described the new species name Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus for the Plesiosaurus discovered by Anning. As the first species name given to a distinctive and well preserved Plesiosaurus skeleton it has come to be regarded as both the type specimen of Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus specifically and of the genus Plesiosaurus as a whole.[15][17]

- Mary Anning collected the Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus specimen now known as BMNH R.1313.[18]

1830s

- Buckland in Conybeare described the new species Plesiosaurus macrocephalus.[19]

- De la Beche illustrated a work titled "Duria Antiquior", meaning "A More Ancient Dorset" for fossil hunter Mary Anning. This work, which prominently features plesiosaurs, has been regarded as the first attempt to accurately reconstruct the Mesozoic world through an artistic medium.[3]

- von Meyer described Pistosaurus. Pistosaurus is believed to be a transitional form linking plesiosaurs to their basal sauropterygian forebears.[20]

1840s

- Owen described the species now known as Colymbosaurus trochanterius,[19] Eurycleidus arcuatus,[19] and Thalassiodracon hawkinsii.[21]

- Owen described the new species Pliosaurus brachydeirus,[19] Pliosaurus brachyspondylus.[19] and Polyptychodon interruptus.[19]

- Sir Richard Owen formally named the pliosaurs.[22]

- Stutchbury described the species now known as Atychodracon megacephalus.

- The trustees of the British Museum of Natural History bought the type specimen of Plesiosaurus from the estate of the first duke of Buckingham, Richard Glenville. The museum catalogued the specimen as BMNH 22656.[16]

1860s

- Carte and Bailey described the species now known as Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni.[19]

- Jules Verne depicted a relict plesiosaur's defeat in combat against an ichthyosaur in Journey to the Center of the Earth.[23]

- Owen described the species now known as Eretmosaurus rugosus[19] and Microcleidus homalospondylus.[19]

- Seeley described the species now known as Microcleidus macropterus.[19]

- Owen described the species now known as Archaeonectrus rostratus.[19]

- An army surgeon named Dr. Theophilus Turner discovered the fossils of a large animal in the Pierre Shale of Kansas, USA. The remains represented the first nearly complete plesiosaur specimen from North America. Turner gave some of its vertebrae to a member of the Union Pacific Railroad's survey named John LeConte. LeConte sent the vertebrae to Edward Drinker Cope for study. Cope recognized the find as a significant plesiosaur discovery and wrote to Turner asking him to excavate and ship the fossils to him.[24]

March, mid

- Cope erected the new genus and species Elasmosaurus platyurus for the fossils sent by Turner in a rushed descriptive manuscript written within two weeks of obtaining them.[25]

March 24

- Cope presented his findings regarding Elasmosaurus to a meeting of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[26]

- Cope described the new species Elasmosaurus platyurus.[19]

- Cope's description of Elasmosaurus was formally published.[26]

September

- William E. Webb and others collected and shipped a plesiosaur specimen to Cope.[27]

- Seeley described the species now known as Liopleurodon pachydeirus[19] and Peloneustes philarchus.[19]

- Cope named the plesiosaur specimen collected by Webb Polycotylus latipinnis.[27]

August

- Cope prepared a preprint for the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society of his Elasmosaurus description, including reconstruction of the animal with a short neck and very long tail. The manuscript was then distributed to other scholars.[26]

1870s

March 8

- Cope's mentor Joseph Leidy gave a presentation reporting his recent discovery that Cope's reconstruction of Elasmosaurus positioned the skull at the end of the tail rather than the end of the neck.[26]

- Leidy's discovery embarrassed Cope, who began spreading notice of an unspecified error in his Elasmosaurus description with an offer to replace it with a corrected version and its second volume.[28]

November

- O. C. Marsh collected a better an additional specimen of Polycotylus in Kansas that was better preserved than the type described by Cope. The specimen is now catalogued as YPM 1125.[29]

- Phillips described the species now known as Pliosaurus macromerus.[19]

- Phillips described the species now known as Cryptoclidus eurymerus.[19]

- Cope described the species now known as Hydralmosaurus serpentinus.[19]

- Cope inaccurately referred to Polycotylus as "the first true plesiosauroid found in America."[27]

- Cope imagined elasmosaurs feeding by craning their necks above the water and striking downward at fish long distances from their bodies.[30]

- B. F. Mudge discovered ten articulated vertebrae in the Fairport Chalk of Kansas that he mistook for ichthyosaur remains. These fossils are now catalogued as KUVP 1325.[31]

- Sauvage described the new species Liopleurodon ferox.[19]

- Joseph Savage discovered a second, better preserved Trinacromerum "anonymum" in Kansas.[31]

- Hector described the new species Mauisaurus haasti.[19]

- Seeley described the new species Muraenosaurus leedsi.[19]

- B. F. Mudge discovered fragments of a large elasmosaur skeleton in the Fort Hays Limestone of Kansas.[32]

- Mudge and Williston excavated the remains another large Kansan plesiosaur, this one from the Smoky Hill Chalk.[32] The specimen may be a Styxosaurus snowii and is currently catalogued as YPM 1644. It was the first plesiosaur Mudge had ever found with gastroliths and the first plesiosaur encountered by Williston in general.[33]

- Hector reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in New Zealand.[34]

- Seeley published a paper intended to help improve the state of science's understanding of plesiosaur shoulder girdle anatomy, which had been muddled by the poor preservation of the fossils many early paleontologists had to rely on for their observations.[35]

- Cope once more portrayed elasmosaurs as feeding by fishing from a distance with heads held above the waterline.[36]

- Blake in Tate and Blake described the new species Plesiosaurus longirostris.[19]

- Lydekker described the species now known as Simolestes indicus.[19]

- Mudge discussed the gastroliths of YPM 1644 in a scientific publication.[33] He concluded that plesiosaur exploited gastroliths to assist in breaking down food the way many modern birds and reptiles do.[37]

- Lydekker described the species now known as Cryptoclidus richardsoni.[19]

1880s

- Oxford acquired the Misses Philpot collection, which included the type specimen of Plesiosaurus macromus. The museum catalogued this specimen as OXFUM J.28587.[38]

- Sollas described the species now known as Attenborosaurus conybeari.[19]

- The British Museum of Natural History purchased the Edgerton collection, which included the complete Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus jaw now known as BMNH R.255.[18]

Spring

- The Smithsonian bought a partial plesiosaur skeleton from Charles Sternberg. The specimen is now catalogued as USNM 4989 and would later serve as the type specimen of the new genus and species Brachauchenius lucasi.[39]

- Harry Seeley mistakenly claimed to have discovered several fossil plesiosaur embryos.[40]

- F. W. Cragin named the genus and species Trinacromerum bentonianum from Kansas.[41]

1890s

- In an article published in the New York Herald, Marsh brought up Cope's anatomic reversal of Elasmosaurus.[28]

- E. P. West excavated a skull and partial neck belonging to the elasmosaur that would come to be named Styxosaurus snowii. The specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 1301.[42]

- Williston described the species now known as Styxosaurus snowii.[19]

- Seeley described the species now known as Muraenosaurus beloclis.[19]

- Marsh described the new species Pantosaurus striatus.[21]

- Charles H. Sternberg obtained two large elasmosaur vertebrae that would later serve as the type specimen of Elasmosaurus sternbergi. The specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 1312.[43]

- F. W. Cragin discovered a partial plesiosaur skeleton and associated gastroliths in what is now recognized as the Kiowa Shale. This specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 1305 and would later be named Plesiosaurus mudgei.[44]

- Williston argued that plesiosaurs ingested gastroliths only accidentally or to relieve "food craving".[37] However, he also observed that the rocks used as gastroliths were more similar to rocks 400–500 miles away in Iowa or the Black Hills of South Dakota than those of the local geology.[45]

- Cragin described the new species Plesiosaurus mudgei for KUVP 1305.[44]

- Dames described the species now known as Seeleysaurus guilelmiimperatoris.[19]

- With guidance from Edward Drinker Cope, paleo-artist Charles R. Knight illustrated an Elasmosaurus platyurus eating a fish. The elasmosaur's neck was erroneously looped into an anatomically impossible figure 8 configuration that evoked the image of "a python grasping at its prey".[46]

- Knight described the new species Megalneusaurus rex.[19]

- A man named Andrew Crombie discovered a fossil jaw fragment with six teeth in Queensland, Australia. The specimen would become the type for the genus Kronosaurus.[47]

20th century

1900s

- Knight described the species now known as Tatenectes laramiensis.[21]

- George F. Sternberg discovered the plesiosaur specimen now known as KUVP 1300 that would later serve as the type specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni.[48]

- Williston described the new species Dolichorhynchops osborni.[19]

- Williston made several changes to plesiosaur taxonomy. One of these was the description of the new genus and species Brachauchenius lucasi, whose type specimen was a partial skeleton discovered in Kansas. This specimen is now catalogued as USNM 4989.[39] He also described the new species Trinacromerum anonymum based on the vertebral series discovered by Mudge in 1872. This specimen is now known as KUVP 1325.[31] Lastly, Williston regarded Plesiosaurus mudgei as a junior synonym of the species Plesiosaurus gouldii.[44] He also commented on the ongoing debate regarding plesiosaur gastroliths, acknowledging the possibility that they were used for ballast while also maintaining openness to his 1893 suggestion that the stones were ingested accidentally.[49]

- Barnum Brown hypothesized that plesiosaurs used their gastroliths in a gizzard-like organ to grind up their invertebrate prey since they had no grinding or crushing teeth to do that job for them.[49]

- Harvard paleontologist Charles R. Eastman, "offended" by Brown's claim that plesiosaurs had a gizzard, criticized the idea in print.[49]

- Williston responded to Eastman, reasserting the evidence for plesiosaur gastroliths by noting that by this time at least 30 specimens containing them had been found.[50]

- Williston described several new taxa and specimens. One of these was the new species Elasmosaurus nobilis.[32] Williston also described the new Elasmosaurus species E. sternbergi based on the vertebrae discovered by Charles H. Sternberg in 1893. He remarked that these fossils were the largest elasmosaur vertebrae that he had ever seen.[43] Lastly, Williston described Marsh's Polycotylus, YPM 1125.[29]

- Williston reported the discovery of another Brachauchenius specimen, although this one was discovered in Texas.[51]

- Williston argued that Brachauchenius lucasi was closely related to Liopleurodon ferox.[52]

- Andrews described the new species Simolestes vorax.[19] and Tricleidus seeleyi.[19]

- Watson described the new species Sthenarasaurus dawkins.[19]

1910s

- Fraas described the species now known as Rhomaleosaurus victor.[19]

- Andrews described the species now known as Leptocleidus capensis.[19]

- Brown described the new species Leurospondylus ultimus.[19]

- Williston criticized portrayals of long-necked plesiosaurs as having unnaturally flexible necks.[46]

- Wegner described the new species Brancasaurus brancai.[19]

- Williston observed that the semicircular canals inside a plesiosaur's ear were well developed, giving them a good sense of balance and coordination.[53]

- The Smithsonian obtained the Tylosaurus specimen with preserved polycotylid stomach contents from Charles Sternberg.[54] The Tylosaurus is catalogued as USNM 8898 and its last supper as USNM 9468.[55]

1920s

- Andrews described the new species Leptocleidus superstes.[19]

- Sternberg observed that being contained in the stomach of a mosasaur might have helped ensure the preservation of the polycotylid now known as USNM 9468 by protecting it from scavenging sharks.[55]

- Huene described the species now known as Hydrorion brachypterygius.[21]

- Heber Longman described Kronosaurus queenslandicus based on the jaw fragment found there by Andrew Crombie in 1899.[47]

- George F. Sternberg discovered a third specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni in Kansas.[48]

- More Kronosaurus fossils were discovered in central Queensland near the site of the type specimen's discovery.[47]

1930s

- Swinton described the new species Macroplata tenuiceps.[19]

- George F. Sternberg and M. V. Walker discovered a well-preserved large elasmosaur specimen.[56]

- Harvard University dispatched a fossil hunting expedition to Queensland, Australia. In Army Downs they discovered a nearly complete specimen of Kronosaurus.[57]

- The "surgeon's photograph" of the Loch Ness monster was hoaxed, cementing the association between plesiosaurs and the mythical beast.[58]

c. 1935

- The University of Nebraska State Museum bought the elasmosaur specimen discovered by Sternberg and Walker in 1931. The specimen is now catalogued as UNSM 1195.[56]

- Russell described the new species Trinacromerum kirki.[19]

- A specimen of Trinacromerum was discovered in a roadside exposure of the Greenhorn Formation in Kansas. The specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 5070.[31]

- A large pliosaur skeleton was found on the banks of Russia's Volga River. However, the specimen was damaged during the excavation and only the skull and chest region were successfully extracted.[59]

1940s

- A complete specimen of Plesiosaurus conybeari, including preserved soft tissues, was destroyed in a bombing raid against Bristol. Fortunately, a cast of the specimen survived in the British Museum.[60]

- White described the new species Seeleyosaurus holzmadensis.[61]

- Cabrera described the new species Aristonectes parvidens.[19]

- Young described the new species Sinopliosaurus weiyuanensis.[21]

- Welles described the new species Aphrosaurus furlongi,[19] Morenosaurus stocki,[19] Thalassomedon haningtoni,[19] Fresnosaurus drescheri,[19] and Hydrotherosaurus alexandrae.[19]

- Welles argued that plesiosaurs did have flexible necks after all.[36]

- Elmer S. Riggs named a new species of Trinacromerum, T. willistoni. The type specimen had been found by a construction crew working on US Highway 81, who donated it to the University of Kansas Museum of Paleontology.[62]

- Riggs described the new species Trinacromerum willistoni based on the 1936 discovery KUVP 5070.[31]

- Soviet paleontologist Nestor Novozhilov described the Volga pliosaur as a new species, Pliosaurus rossicus.[59]

- Novozhilov described the species now known as Pliosaurus irgisensis.[19]

- Welles described the species now known as Libonectes morgani.[19]

- de la Torre and Rojas described the species now known as Vinialesaurus caroli.[21]

1950s

- Alfred Sherwood Romer helped mount the Kronosaurus discovered in Queensland by the 1930s Harvard expedition for the University's Museum of Comparative Zoology. The poorly preserved bones required a significant amount of plaster for the restoration, earning the specimen the mocking nickname "Plasterosaurus".[57] The final mount was 42 feet long, probably due to Romer overestimating the number of vertebrae in its spine; a more likely length is about 35 feet.[63]

- Fossil hunters Robert and Frank Jennrich serendipitously discovered a partial Brachauchenius skeleton when looking for sharks teeth.[52]

- Shuler, like Williston in 1914, found elasmosaurs to have relatively inflexible necks.[36] He also found elasmosaurs to have stereoscopic vision, which would have been useful for hunting small prey.[53]

October

- George Sternberg excavated the Brachauchenius discovered by the Jennriches. This specimen, now known as FHSM VP-321, was both larger and better preserved than the Brachauchenius type specimen. Although it was put on display soon after discovery, it would not be described for the scientific literature for nearly 50 years.[52]

- Welles argued that the "Elasmosaurus sternbergi" type specimen was actually pliosaur vertebrae.[43]

- A private landowner in Kansas donated some Elasmosaurus vertebrae to the Sternberg Museum. These fossils are now catalogued as FHSM VP-398.[64]

1960s

- Tarlo described the new species Pliosaurus andrewsi.[19]

- Welles described the species now known as Callawayasaurus colombiensis.[21]

- Welles reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in South America.[34]

- Chatterjee and Zinsmeister reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in Antarctica.[34]

- Barney H. Newman and Lambert Beverly Halstead Tarlo argued that long-necked plesiosaur flippers could only move horizontally, and while maneuverable, they were confined to surface waters by an inability to dive.[65]

- South Australian opal miners John and Molly Addyman discovered a plesiosaur whose remains had been converted to opal.[66]

1970s

- Beverly Halstead reclassified the Volga pliosaur, Pliosaurus rossicus, to the genus Liopleurodon.[59]

- Paul Johnston discovered plesiosaur fossils in a roadside exposure of the Greenhorn Formation in Kansas.[67] During the excavation the dig site was scouted by two suspicious men. After a break from digging the Johnston team returned to find all of the fossils crudely extracted from the rock except for a flipper that the team had reburied. Based on the flipper, the stolen plesiosaur could be identified as Trinacromerum bentonianum.[68]

- Jane Ann Robinson published a paper on plesiosaur locomotion concluding that they really did swim by "underwater flight" like sea turtles or penguins.[8]

- Ochev described the species now known as Georgiasaurus penzensis.[19]

- Robinson publishes follow up research to her previous publication on plesiosaur locomotion.[9] This second paper notably concluded that plesiosaurs were incapable of leaving the water.[69]

1980s

- Dong described the new species Bishanopliosaurus youngi.[19]

- Michael Alan Taylor published a paper concluding that plesiosaurs would have been capable of moving on land after all because their spinal column was too arched for their lungs to collapse.[70]

- Brown described the new species Kimmerosaurus langhami.[19]

- Brown emended the species Plesiosaurus guilelmiiperatoris originally described by Dames in 1895.[15]

- Taylor argued that plesiosaurs used their gastroliths to adjust buoyancy or to help stay level and balanced while swimming.[37]

- Samuel F. Tarsitano and Jürgen Riess published a paper harshly critical of Robinson's previous work on plesiosaur locomotion. However, while criticizing Robinson's work they were reluctant to make any positive claims of their own, concluding that the details of plesiosaur locomotion were "unknown".[9]

- Richard A. Thulborn published the results of his recent re-examination of the purported plesiosaur embryos discovered by Harry Govier Seeley. Thulborn concluded that Seeley's supposed embryos were actually nodules of mudstone and shale derived from sediments that once filled in a crustacean burrow system and were not even animal body fossils.[40]

- Delair described the new species Bathyspondylus swindoniensis.[21]

- The partial remains of a large pliosaur, initially mistaken for a dinosaur, were discovered near Aramberri, Mexico.[59]

- Zhang described the new species Yuzhoupliosaurus chengjiangensis.[21]

- A South Australian opal miner named Joe Vida discovered the skeleton of a juvenile plesiosaur whose remains had converted to opal. Its preparator, Paul Willis nicknamed it Eric. An entrepreneur named Sid Londish bought the specimen and funded its preparation, but went bankrupt. When the specimen was put up for auction fear spread that a potential buyer might break the specimen down for its gemstone value. A television drive was arranged on behalf of the Australian Museum. The Museum succeeded in raising 340,000 dollars to buy the specimen, whose gemstone value was about $300,000. Eric was later identified as a specimen of Leptocleidus.[22]

- Wiffen and Moisley described the new species Tuarangisaurus keysei.[21]

- Judith Massare published an analysis of plesiosaur feeding habits. She concluded that the long-necked plesiosauroids ate soft prey. Liopleurodon and its relatives, on the other hand, had teeth resembling those of killer whales and probably ate larger, bonier prey.[51]

- Orville Bonner discovered a specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni that was later seen to preserve developing young inside it.[71]

- Judy Massare analyzed Mesozoic marine reptile swimming abilities and found that long-necked plesiosaurs would have been significantly slower than pliosaurs due to excess drag incurred from the length of the neck.[72]

- The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History acquired the Dolichorhynchops osborni specimen discovered by Bonner and catalogued it as LACMNH 129639.[44]

- Beverly Halstead published a paper suggesting that plesiosaurs swam using all four flippers paired with an undulatory motion of the body comparable to a sea lion's.[73]

- Nakaya reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in Japan.[34]

1990s

- The world's smallest plesiosaur, between four and five feet in length, was discovered near Charmouth on the Dorset Coast.[74]

- Sciau et al. described the species now known as Occitanosaurus tournemirensis.[21]

- Gasparini and Spalleti described the new species Sulcusuchus erraini.[21]

- Stewart noted a relative paucity of plesiosaur fossils from the lower portions of the Smoky Hill Chalk in a manuscript for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.[75]

- Tim Tokaryk of the Royal Saskatchewan Museum discovers a new kind of plesiosaur, Dolichorhynchops herschelensis near Herschel, Saskatchewan.[76]

May

- J. D. Stewart, accompanied by Everhart, discovered a nearly complete Dolichorhynchops rear flipper in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk. Unfortunately it was too late to correct the erroneous statements in his aforementioned paper regarding the supposed rarity of plesiosaurs in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk. The flipper is now catalogued as LACMNH 148920.[77]

October

- Stewart's paper, complete with his now-erroneous statements, was published in the Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook in honor of the society's 50th anniversary meeting in Lawrence that year.[75]

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk