A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

First edition of Ulysses by James Joyce, published by Paris-Shakespeare, 1922. The colour of the cover was meant to match the blue of the Greek flag.[1][2] | |

| Author | James Joyce |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Modernist novel |

| Set in | Dublin, 16–17 June 1904 |

| Publisher | Shakespeare and Company |

Publication date | 2 February 1922 |

| Media type | Print: hardback |

| Pages | 732 |

| 823.912 | |

| LC Class | PR6019.O8 U4 1922 |

| Preceded by | A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man |

| Text | Ulysses (novel) at Wikisource |

Ulysses is a modernist novel by the Irish writer James Joyce. Parts of it were first serialized in the American journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920, and the entire work was published in Paris by Sylvia Beach on 2 February 1922, Joyce's fortieth birthday. It is considered one of the most important works of modernist literature[3] and has been called "a demonstration and summation of the entire movement".[4] According to the writer Declan Kiberd, "before Joyce, no writer of fiction had so foregrounded the process of thinking".[5]

The novel chronicles the experiences of three Dubliners over the course of a single day, 16 June 1904. Ulysses is the Latinised name of Odysseus, the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey, and the novel establishes a series of parallels between Leopold Bloom and Odysseus, Molly Bloom and Penelope, and Stephen Dedalus and Telemachus. There are also correspondences with other literary and mythological figures, and such themes as antisemitism, human sexuality, British rule in Ireland, Catholicism, and Irish nationalism are treated in the context of early 20th-century Dublin. The novel is highly allusive and written in a variety of styles.

Since its publication, the book has attracted controversy and scrutiny, ranging from an obscenity trial in the United States in 1921 to protracted textual "Joyce Wars". The novel's stream of consciousness technique, careful structuring, and experimental prose—replete with puns, parodies, epiphanies, and allusions—as well as its rich characterisation and broad humour have led it to be regarded as one of the greatest literary works; Joyce fans worldwide now celebrate 16 June as Bloomsday.

Background

Joyce first encountered the figure of Odysseus/Ulysses in Charles Lamb's Adventures of Ulysses, an adaptation of the Odyssey for children, which seems to have established the Latin name in Joyce's mind. At school he wrote an essay on the character, titled "My Favourite Hero".[6][7] Joyce told Frank Budgen that he considered Ulysses the only all-round character in literature.[8] He considered writing another short story for Dubliners, to be titled "Ulysses" and based on a Dublin Jew named Alfred H. Hunter, a putative cuckold.[9] The idea grew from a story in 1906, to a "short book" in 1907,[10] to the vast novel he began in 1914.

Locations

- Leopold Bloom's home at 7 Eccles Street[12] – Episode 4, Calypso; Episode 17, Ithaca; and Episode 18, Penelope

- Post office, Westland Row – Episode 5, Lotus Eaters

- Sweny's pharmacy, Lombard Street, Lincoln Place[13] (where Bloom bought soap) – Episode 5, Lotus Eaters

- The Freeman's Journal, Prince's Street,[14] off of O'Connell Street – Episode 7, Aeolus

- Davy Byrne's pub – Episode 8, Lestrygonians

- National Library of Ireland – Episode 9, Scylla and Charybdis

- Ormond Hotel[15] on the banks of the Liffey – Episode 11, Sirens

- Barney Kiernan's pub – Episode 12, Cyclops

- Maternity hospital – Episode 14, Oxen of the Sun

- Bella Cohen's brothel – Episode 15, Circe

- Cabman's shelter, Butt Bridge – Episode 16, Eumaeus

The action of the novel moves from one side of Dublin Bay to the other, opening in Sandycove to the South of the city and closing on Howth Head to the North.

Structure

Ulysses is divided into the three books (marked I, II, and III) and 18 episodes. The episodes do not have chapter headings or titles, and are numbered only in Gabler's edition. In the various editions, the breaks between episodes are indicated in different ways; in the Modern Library edition, for example, each episode begins at the top of a new page.

Joyce seems to have relished his book's obscurity, saying he had "put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that's the only way of insuring one's immortality".[16] The judge who decided that Ulysses was not obscene admitted that it "is not an easy book to read or to understand", and advised reading "a number of other books which have now become its satellites".[17] One such book available at the time was Herbert Gorman's first book on Joyce, which included his own brief list of correspondences between Ulysses and the Odyssey.[18] Another was Stuart Gilbert's study of Ulysses, which included a schema of the novel Joyce created.[19] Gilbert was later quoted in the legal brief prepared for the obscenity trial.[20] Joyce had already sent Carlo Linati a different schema.[21] The Gilbert and Linati schemata made the links to the Odyssey clearer and also explained the work's structure.

Joyce and Homer

The 18 episodes of Ulysses "roughly correspond to the episodes in Homer's Odyssey".[22] In Homer's epic, Odysseus, "a Greek hero of the Trojan War ... took ten years to find his way from Troy to his home on the island of Ithaca".[23] Homer's poem includes violent storms and a shipwreck, giants, monsters, gods, and goddesses, while Joyce's novel takes place during an ordinary day in early 20th-century Dublin. Leopold Bloom, "a Jewish advertisement canvasser", corresponds to Odysseus in Homer's epic; Stephen Dedalus, the protagonist of Joyce's earlier, largely autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, corresponds to Odysseus's son Telemachus; and Bloom's wife Molly corresponds to Penelope, Odysseus's wife, who waited 20 years for him to return.[24]

The Odyssey is divided into 24 books, which are divided into 3 parts of 4, 8, and 12 books. Although Ulysses has fewer episodes, their division into 3 parts of 3, 12, and 3 episodes is determined by the tripartite division of The Odyssey.[25] Joyce referred to the episodes by their Homeric titles in his letters. The novel's text does not include the episode titles used below, which originate from the Linati and Gilbert schemata. Joyce scholars have drawn upon both to identify and explain the parallels between Ulysses and The Odyssey.[26][27][28][29]

Scholars have argued that Victor Berard's Les Phéniciens et l'Odyssée, which Joyce discovered in Zurich while writing Ulysses, influenced his creation of the novel's Homeric parallels.[30][31] Berard's theory that The Odyssey had Semitic roots accords with Joyce's reincarnation of Odysseus as the Jewish Leopold Bloom.[32]

Ezra Pound regarded the Homeric correspondences as "a scaffold, a means of construction, justified by the result, and justifiable by it only. The result is a triumph in form, in balance, a main schema with continuous weaving and arabesque."[33] For T. S. Eliot, the Homeric correspondences had "the importance of a scientific discovery". He wrote, "In manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity ... Mr. Joyce is pursing a method which others must pursue after him." This method "is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history".[34]

Besides the Homeric parallels, the Gilbert and the Linati schemata identify other aspects of the episodes. The latter lists Hamlet and Shakespeare. Stephen Dedalus sets forth a theory of Hamlet based on 12 lectures, now lost, that Joyce gave in Trieste in 1912.[35] (Scholars have explained the Hamlet parallels in considerable detail.[36][37][38][39][40]) There are also correspondences with other figures, including Christ, Elijah, Moses, Dante, and Don Giovanni.[41] Like Shakespeare, Dante was a major influence on Joyce.[42] It has been argued that the interrelationship of Joyce, Dedalus, and Bloom is defined in the Incarnation doctrines the novel cites.[43]

Plot summary

Part I: Telemachia

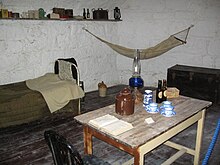

Episode 1, Telemachus

At 8 a.m., Malachi "Buck" Mulligan, a boisterous medical student, calls aspiring writer Stephen Dedalus up to the roof of the Sandycove Martello tower, where they both live. There is tension between Dedalus and Mulligan stemming from a cruel remark Dedalus overheard Mulligan make about his recently deceased mother and from the fact that Mulligan has invited an English student, Haines, to stay with them. The three men eat breakfast and walk to the shore, where Mulligan demands from Stephen the key to the tower and a loan. The three make plans to meet at a pub, The Ship, at 12:30pm. Departing, Stephen decides that he will not return to the tower that night, as Mulligan, the "usurper", has taken it over.

Episode 2, Nestor

Stephen is teaching a history class on the victories of Pyrrhus of Epirus. After class, one student, Cyril Sargent, stays behind so that Stephen can show him how to do a set of algebraic exercises. Stephen looks at Sargent's ugly face and tries to imagine Sargent's mother's love for him. He then visits unionist school headmaster Garrett Deasy, from whom he collects his pay. Deasy asks Stephen to take his long-winded letter about foot-and-mouth disease to a newspaper office for printing. The two discuss Irish history and Deasy lectures on what he believes is the role of Jews in the economy. As Stephen leaves, Deasy jokes that Ireland has "never persecuted the Jews" because the country "never let them in". This episode is the source of some of the novel's best-known lines, such as Dedalus's claim that "history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake" and that God is "a shout in the street".

Episode 3, Proteus

Stephen walks along Sandymount Strand for some time, mulling various philosophical concepts, his family, his life as a student in Paris, and his mother's death. As he reminisces he lies down among some rocks, watches a couple whose dog urinates behind a rock, scribbles some ideas for poetry and picks his nose. This chapter is characterised by a stream of consciousness narrative style that changes focus wildly. Stephen's education is reflected in the many obscure references and foreign phrases employed in this episode, which have earned it a reputation for being one of the book's most difficult chapters.

Part II: Odyssey

Episode 4, Calypso

The narrative shifts abruptly. The time is again 8 a.m., but the action has moved across the city and to the second protagonist of the book, Leopold Bloom, a part-Jewish advertising canvasser. The episode opens with the line "Mr. Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls." After starting to prepare breakfast, Bloom decides to walk to a butcher to buy a pork kidney. Returning home, he prepares breakfast and brings it with the mail to his wife Molly as she lounges in bed. One of the letters is from her concert manager Blazes Boylan, with whom she is having an affair. Bloom reads a letter from their daughter Milly Bloom, who tells him about her progress in the photography business in Mullingar. The episode closes with Bloom reading a magazine story titled "Matcham's Masterstroke", by Mr. Philip Beaufoy, while defecating in the outhouse.

Episode 5, Lotus Eaters

While making his way to Westland Row post office Bloom is tormented by the knowledge that Molly will welcome Boylan into her bed later that day. At the post office he surreptitiously collects a love letter from one 'Martha Clifford' addressed to his pseudonym, 'Henry Flower'. He meets an acquaintance, and while they chat, Bloom attempts to ogle a woman wearing stockings, but is prevented by a passing tram. Next, he reads the letter from Martha Clifford and tears up the envelope in an alley. He wanders into a Catholic church during a service and muses on theology. The priest has the letters I.N.R.I. or I.H.S. on his back; Molly had told Bloom that they meant I have sinned or I have suffered, and Iron nails ran in. He buys a bar of lemon soap from a chemist. He then meets another acquaintance, Bantam Lyons, who mistakenly takes him to be offering a racing tip for the horse Throwaway. Finally, Bloom heads towards the baths.

Episode 6, Hades

The episode begins with Bloom entering a funeral carriage with three others, including Stephen's father. They drive to Paddy Dignam's funeral, making small talk on the way. The carriage passes both Stephen and Blazes Boylan. There is discussion of various forms of death and burial. Bloom is preoccupied by thoughts of his dead infant son, Rudy, and the suicide of his own father. They enter the chapel for the service and subsequently leave with the coffin cart. Bloom sees a mysterious man wearing a mackintosh during the burial. Bloom continues to reflect upon death, but at the end of the episode rejects morbid thoughts to embrace "warm fullblooded life".

Episode 7, Aeolus

At the office of the Freeman's Journal, Bloom attempts to place an ad. Although initially encouraged by the editor, he is unsuccessful. Stephen arrives bringing Deasy's letter about foot-and-mouth disease, but Stephen and Bloom do not meet. Stephen leads the editor and others to a pub, relating an anecdote on the way about "two Dublin vestals". The episode is broken into short segments by newspaper-style headlines, and is characterised by an abundance of rhetorical figures and devices.

Episode 8, Lestrygonians

Bloom's thoughts are peppered with references to food as lunchtime approaches. He meets an old flame, hears news of Mina Purefoy's labour, and helps a blind boy cross the street. He enters the restaurant of the Burton Hotel, where he is revolted by the sight of men eating like animals. He goes instead to Davy Byrne's pub, where he consumes a gorgonzola cheese sandwich and a glass of burgundy, and muses upon the early days of his relationship with Molly and how the marriage has declined: "Me. And me now." Bloom's thoughts touch on what goddesses and gods eat and drink. He ponders whether the statues of Greek goddesses in the National Museum have anuses as do mortals. On leaving the pub Bloom heads toward the museum, but spots Boylan across the street and, panicking, rushes into the gallery across the street from the museum.

Episode 9, Scylla and Charybdis

At the National Library, Stephen explains to some scholars his biographical theory of the works of Shakespeare, especially Hamlet, which he argues are based largely on the posited adultery of Shakespeare's wife. Buck Mulligan arrives and interrupts to read out the telegram that Stephen had sent him indicating that he would not make their planned rendezvous at The Ship. Bloom enters the National Library to look up an old copy of the ad he has been trying to place. He passes in between Stephen and Mulligan as they exit the library at the end of the episode.

Episode 10, Wandering Rocks

In this episode, nineteen short vignettes depict the movements of various characters, major and minor, through the streets of Dublin. The episode begins by following Father Conmee, a Jesuit priest, on his trip north, and ends with an account of the cavalcade of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, William Ward, Earl of Dudley, through the streets, which is encountered by several characters from the novel.

Episode 11, Sirens

In this episode, dominated by motifs of music, Bloom has dinner with Stephen's uncle at the Ormond hotel, while Molly's lover, Blazes Boylan, proceeds to his rendezvous with her. While dining, Bloom listens to the singing of Stephen's father and others, watches the seductive barmaids, and composes a reply to Martha Clifford's letter.

Episode 12, Cyclops

This episode is narrated by an unnamed denizen of Dublin who works as a debt collector. The narrator goes to Barney Kiernan's pub where he meets a character referred to only as "The Citizen". This character is believed to be a satirisation of Michael Cusack, a founder member of the Gaelic Athletic Association.[44] When Leopold Bloom enters the pub, he is berated by the Citizen, who is a fierce Fenian and anti-Semite. The episode ends with Bloom reminding the Citizen that his Saviour was a Jew. As Bloom leaves the pub, the Citizen throws a biscuit tin at Bloom's head, but misses. The episode is marked by extended tangents made in voices other than that of the unnamed narrator; these include streams of legal jargon, a report of a boxing match, Biblical passages, and elements of Irish mythology.

Episode 13, Nausicaa

All the action of the episode takes place on the rocks of Sandymount Strand, the shoreline that Stephen visited in Episode 3. A young woman, Gerty MacDowell, is seated on the rocks with her two friends, Cissy Caffrey and Edy Boardman. The girls are taking care of three children, a baby, and four-year-old twins named Tommy and Jacky. Gerty contemplates love, marriage and femininity as night falls. The reader is gradually made aware that Bloom is watching her from a distance. Gerty teases the onlooker by exposing her legs and underwear, and Bloom, in turn, masturbates. Bloom's masturbatory climax is echoed by the fireworks at the nearby bazaar. As Gerty leaves, Bloom realises that she has a lame leg, and believes this is the reason she has been "left on the shelf". After several mental digressions he decides to visit Mina Purefoy at the maternity hospital. It is uncertain how much of the episode is Gerty's thoughts, and how much is Bloom's sexual fantasy. Some believe that the episode is divided into two halves: the first half the highly romanticized viewpoint of Gerty, and the other half that of the older and more realistic Bloom.[45] Joyce himself said, however, that "nothing happened between . It all took place in Bloom's imagination".[45] Nausicaa attracted immense notoriety while the book was being published in serial form. It has also attracted great attention from scholars of disability in literature.[46] The style of the first half of the episode borrows from (and parodies) romance magazines and novelettes. Bloom's contemplation of Gerty parodies Dedalus's vision of the wading girl at the seashore in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.[47][48]

Episode 14, Oxen of the Sun

Bloom visits the maternity hospital where Mina Purefoy is giving birth, and finally meets Stephen, who has been drinking with his medical student friends and is awaiting the promised arrival of Buck Mulligan. As the only father in the group of men, Bloom is concerned about Mina Purefoy in her labour. He starts thinking about his wife and the births of his two children. He also thinks about the loss of his only 'heir', Rudy. The young men become boisterous, and start discussing such topics as fertility, contraception and abortion. There is also a suggestion that Milly, Bloom's daughter, is in a relationship with one of the young men, Bannon. They continue on to a pub to continue drinking, following the successful birth of a son to Mina Purefoy. This chapter is remarkable for Joyce's wordplay, which, among other things, recapitulates the entire history of the English language. After a short incantation, the episode starts with latinate prose, Anglo-Saxon alliteration, and moves on through parodies of, among others, Malory, the King James Bible, Bunyan, Pepys, Defoe, Sterne, Walpole, Gibbon, Dickens, and Carlyle, before concluding in a Joycean version of contemporary slang. The development of the English language in the episode is believed to be aligned with the nine-month gestation period of the foetus in the womb.[49]

Episode 15, Circe

Episode 15 is written as a play script, complete with stage directions. The plot is frequently interrupted by "hallucinations" experienced by Stephen and Bloom—fantastic manifestations of the fears and passions of the two characters. Stephen and his friend Lynch walk into Nighttown, Dublin's red-light district. Bloom pursues them and eventually finds them at Bella Cohen's brothel where, in the company of her workers including Zoe Higgins, Florry Talbot and Kitty Ricketts, he has a series of hallucinations regarding his sexual fetishes, fantasies and transgressions. In one of these hallucinations, Bloom is put in the dock to answer charges by a variety of sadistic, accusing women including Mrs Yelverton Barry, Mrs Bellingham and the Hon Mrs Mervyn Talboys. In another of Bloom's hallucinations, he is crowned king of his own city, which is called Bloomusalem—Bloom imagines himself being loved and admired by Bloomusalem's citizens, but then imagines himself being accused of various charges. As a result, he is burnt at the stake and several citizens pay their respects to him as he dies.

Then the hallucination ends, Bloom finds himself next to Zoe, and the two talk. After they talk, Bloom continues to encounter other miscellaneous hallucinations, including one in which he converses with his grandfather Lipoti Virag, who lectures him about sex, among other things. At the end of the hallucination, Bloom is speaking with some prostitutes when he hears a sound coming from downstairs. He hears heels clacking on the staircase, and he observes what appears to be a male form passing down the staircase. He speaks with Zoe and Kitty for a moment, and then sees Bella Cohen come into the brothel. He observes her appearance and talks with her for a little while. But this conversation subsequently begins another hallucination, in which Bloom imagines Bella to be a man named Mr. Bello and Bloom imagines himself to be a woman. In this fantasy, Bloom imagines himself (or "herself", in the hallucination) being dominated by Bello, who both sexually and verbally humiliates Bloom. Bloom also interacts with other imaginary characters in this scene before the hallucination ends.

After the hallucination ends, Bloom sees Stephen overpay at the brothel, and decides to hold onto the rest of Stephen's money for safekeeping. Stephen hallucinates that his mother's rotting cadaver has risen up from the floor to confront him. He cries Non serviam!, uses his walking stick to smash a chandelier, and flees the room. Bloom quickly pays Bella for the damage, then runs after Stephen. He finds Stephen engaged in an argument with an English soldier, Private Carr, who, after a perceived insult to the King, punches Stephen. The police arrive and the crowd disperses. As Bloom tends to Stephen, he has a hallucination of his deceased son, Rudy, as an 11-year-old.

Part III: Nostos

Episode 16, Eumaeusedit

Bloom takes Stephen to a cabman's shelter near Butt Bridge to restore him to his senses. There, they encounter a drunken sailor, D. B. Murphy (W. B. Murphy in the 1922 text). The episode is dominated by the motif of confusion and mistaken identity, with Bloom, Stephen and Murphy's identities being repeatedly called into question. The narrative's rambling and laboured style in this episode reflects the protagonists' nervous exhaustion and confusion.

Episode 17, Ithacaedit

Bloom returns home with Stephen, makes him a cup of cocoa, discusses cultural and linguistic differences between them, considers the possibility of publishing Stephen's parable stories, and offers him a place to stay for the night. Stephen refuses Bloom's offer and is ambiguous in response to Bloom's proposal of future meetings. The two men urinate in the backyard, Stephen departs and wanders off into the night,[50] and Bloom goes to bed, where Molly is sleeping. She awakens and questions him about his day. The episode is written in the form of a rigidly organised and "mathematical" catechism of 309 questions and answers, and was reportedly Joyce's favourite episode in the novel. The deep descriptions range from questions of astronomy to the trajectory of urination and include a list of 25 men that purports to be the "preceding series" of Molly's suitors and Bloom's reflections on them. While describing events apparently chosen randomly in ostensibly precise mathematical or scientific terms, the episode is rife with errors made by the undefined narrator, many or most of which are intentional by Joyce.[51]

Episode 18, Penelopeedit

The final episode consists of Molly Bloom's thoughts as she lies in bed next to her husband. The episode uses a stream-of-consciousness technique in eight paragraphs and lacks punctuation. Molly thinks about Boylan and Bloom, her past admirers, including Lieutenant Stanley G. Gardner, the events of the day, her childhood in Gibraltar, and her curtailed singing career. She also hints at a lesbian relationship in her youth, with a childhood friend, Hester Stanhope. These thoughts are occasionally interrupted by distractions, such as a train whistle or the need to urinate. Molly is surprised by the early arrival of her menstrual period, which she ascribes to her vigorous sex with Boylan. The episode concludes with Molly's remembrance of Bloom's marriage proposal, and of her acceptance: "he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes."

Joyce, Shakespeare, Aquinasedit

In the Library episode, Stephen Dedalus explains his "idea of Hamlet". His exposition is based on 12 lectures, now lost, that Joyce gave in Trieste in 1912.[52] There are implied parallels with Ulysses.[36][37][38][39][53][40] Harry Blamires has identified the essential ones, as well as parallels with Christian theology: "Joyce puts himself in Ulysses as both Father (Ghost-Father) and Son. Shakespeare puts himself in Hamlet as both Ghost-Father and Son. God enters His own world as Holy Ghost and as Son."[54]

In "Telemachus", Malachi "Buck" Mulligan claims that Stephen's theory draws on Thomas Aquinas for support, and in the Library episode he mentions Stephen's study of Aquinas's Summa contra Gentiles.[55] Joyce apparently owned three copies. One was an English abridgment with annotations, which he had purchased in Trieste in 1913–1914.[55] This book, which he told Ezra Pound he had consulted on his behalf,[56] was Joseph Rickaby's Of God and His Creatures.[57]

Shortly after his Hamlet theory is mentioned in "Telemachus", Stephen thinks of doctrines on the Incarnation that Aquinas discusses in the Summa: the Catholic doctrine of consubstantiality and the heresies of Sabellius, Photius, Arius, and Valentine. During his exposition in the Library, Stephen mentions both the Sabellian heresy and Aquinas's refutation. For Blamires, "Stephen's study of Hamlet is among things and analogically theological one concerning the operation of the three Persons of the Trinity."[58]

The distinction between consubstantiality and Sabellianism explains Shakespeare's double presence in Hamlet. The doctrine of consubstantiality holds that Father and Son are separate persons sharing the same nature.[59] Shakespeare and Hamlet are spiritually consubstantial. Hamlet is "the son of his soul", as Hamnet was "the son of his body". (Valentine, next-to-last on Stephen's list, also held that Father and Son were consubstantial, but, as a Gnostic, denied that Christ became flesh.) Sabellius taught that Father, Son, and Holy Ghost were not separate persons, but manifestations of a single divine being.[60] When the Holy Ghost descended, it was actually the Father in another form. Shakespeare is "Ghost-Father", Hamlet's spiritual father playing the role of the Ghost: "I am thy father's spirit." At the Baptism of Christ, Joyce's actual source for the "epiphany", the Holy Ghost descends and the Father speaks. In the Gospel of Mark, He addresses Christ: "Thou art my beloved Son."[61]

For Blamires, Stephen's contention that Shakespeare is both King Hamlet and the Prince "is hint enough that Joyce has represented himself in both Leopold Bloom and Stephen".[62] Like Shakespeare and Hamlet, Joyce and Stephen are spiritually consubstantial. Hamlet is a younger version of Shakespeare, Stephen a younger version of Joyce.[63] The Sabellian heresy defines Joyce's relation to Bloom. Like Shakespeare and King Hamlet, Joyce and Bloom are the same person. Sabellius held that the Father incarnated himself as Christ. Bloom is the form Joyce assumes in Ulysses. Hugh Kenner has written, "Joyce built Bloom, as he did all characters, by playing him."[64] Like the Sabellian Father, Joyce became a Jew. (Bloom says in "Cyclops", "Christ was a jew like me.") In "Calypso", Bloom refers to "Metempsychosis ... the transmigration of souls." Bloom then is Joyce reincarnated, his "soul" in another "body".[63]

In "Circe", Bloom and Stephen share the apparition of Shakespeare, who speaks "in dignified ventriloquy". In the Library episode, Stephen characterizes the Ghost of Hamlet's father as a "voice". Bloom is "Ghost/Father" in Ulysses, in that, as Joyce's reincarnation, he is also his voice. For example, he advocates "love ... the opposite of hatred".[65] Most often Bloom speaks for Joyce silently, in his interior monologue. Hugh Kenner writes, "Bloom holds very much the opinions of Joyce on a wide range of Dublin topics: on Irish nationalism, on drunkenness, on literary pretensions, on death and Resurrection, on marriage, on the hierarchy of the virtues."[64]

Though only consubstantial with Joyce, Stephen is also his voice. The heresy of Photius, first on his list, holds the key. The schism between the Latin and Greek Churches was due to the Filioque clause in the Nicene Creed, and Photius was mainly responsible.[66] In juxtaposing Mulligan with Photius in "Telemachus", Stephen is recalling Mulligan's parody of his "idea of Hamlet". It ends with "he himself is the ghost of his own father". Haines points to Stephen, asking, "He himself?"[67] According to Aquinas, without the Filioque clause "It will be true then to say that the Holy Ghost is the Son, and the Son the Holy Ghost." At the Baptism, the Holy Ghost descends and the Father's voice is heard.[68] Not only Joyce's consubstantial son, Stephen is also his voice.[69] Through him, for example, Joyce again delivers his 1912 lectures on Hamlet. Like Bloom, Stephen most often speaks for Joyce in his thoughts.

On occasion, Joyce's voice intrudes directly into the interior monologue. In "Lotus Eaters", he uses the words of Consecration, "This is my body", to identify Bloom as his reincarnation.[70] Another example is the paragraph in "Telemachus" which lists the doctrines on the Incarnation. The paragraph comes during a conversation with Haines. Kenner estimates it would take Stephen at least a minute to speak the paragraph to himself, "longer than he seems likely to have chattered on". He concludes that the paragraph "exits alongside the narrative, with Stephen's presence to excuse it".[71] In other words, Joyce himself is introducing the theological parallels crucial to understanding his double presence in the novel.[72]

The paragraph refers to the "Symbol creed of the apostles in the mass for pope Marcellus". In fact, the Nicene Creed, not the Apostles' Creed, is sung or recited during Mass. The Nicene Creed contains a narrative of Christ's mission embellished with Catholic doctrine. The Apostles' Creed, the oldest in Catholicism, offers only the narrative.[73]

I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead. He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead.

The Apostles' Creed reflects the doctrine of consubstantiality, and so applies to Stephen.[74]

Just before mentally reciting his parody of the Apostles' Creed in the Library episode, Stephen thinks of Photius, Mulligan, and the German anarchist Johann Most. Mulligan's "Ballad of Joking Jesus" is also a parody of the Apostles' Creed. [75] Most is the immediate source for Stephen's parody.[76][77] Photius is a reminder that Stephen is Joyce's voice in Ulysses. The creed comes directly from him.

He Who Himself begot middler the Holy Ghost and Himself sent Himself, Agenbuyer (Christ[78]), between Himself and others, Who, put upon by His fiends, stripped and whipped, was nailed like bat to barndoor, starved on crosstree, Who let Him bury, stood up, harrowed hell, fared into heaven and there these nineteen hundred years sitteth on the right hand of His Own Self but yet shall come in the latter day to doom the quick and dead when all the quick shall be dead already.

Stephen's parody reflects the Sabellian heresy, and so applies to Bloom.[79]

Blamires has written that "Joyce's created world ... is like God's world ... a world into which its own creator has entered, in which he has suffered, and from which he has been raised up."[80] Both Bloom and Stephen are Christ figures. Both will suffer, die, and rise. In "Cyclops", Bloom is crucified by the Citizen and resurrected by the narrator. In "Circe", Stephen is crucified by Private Carr and resurrected by Bloom.[81]

Stephen puts the heretic Arius second on his list in "Telemachus" and thinks of him later in "Proteus". The Arians held that the Son "was one with God the Father, not by nature, but by a union of wills, and by participation in the likeness of God beyond other creatures".[82] William York Tindall has said that Stephen sees his future in Bloom.[83] Kenner has written, "Arius ... proposed a relation of adoption such as is to subsist between Stephen and Bloom".[84][85]

As narratives of Christ's mission, both the Apostles' Creed and Stephen's parody end with the Last Judgment, the Second Coming of Christ. Blamires writes, "fortunately Joyce is now sitting on His own right hand (which held the pen that wrote Ulysses) and he will come again (he is already here) to doom the quick and the dead."[62] In Ulysses there are two Christ figures; the first coming of Christ is intertwined with the second. Bloom and Stephen not only endure but pass judgment. S. L. Goldberg refers to "the exploration of moral order" in Ulysses: "self-knowledge, self-realization, detachment, human completeness, balance, are Joyce's key concepts".[86] In their thoughts, Bloom and Stephen judge others based on such concepts.

Aquinas speaks of the radiant "souls of the just" at the Last Judgment: "then the soul in the enjoyment of the vision of God will be replenished with a spiritual brightness italics his, so by an overflow from soul to body, the body itself, in its way, will be clad in a halo and glory of brightness."[87] In the aesthetic theory put forth in Stephen Hero, "Claritas is quidditas". At the transfiguration of Christ, he is radiant, his divine nature showing forth. Transfiguration of the artist's self-images is continuous. While he remains invisible, like God the Father, his self-images reveal his nature. The transfiguration is paralleled in the revelation of the artist's nature in his self-images. The bodily radiance of the just is paralleled in his revelation of other natures in his reincarnation of them.[88]

In "Oxen of the Sun", Stephen declares, "Either transubstantiality or consubstantiality but in no case subsubstantiality." The terms refer, as Richard Ellmann has noted, to opposing doctrines on the Incarnation.[89] The first is obviously a coinage formed from transubstantiation. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the priest is said to make "the great God of heaven come down upon the altar and take the form of bread and wine".[90] Sabellius held that the Father became his own Son when, born of the Virgin Mary, He took human form.[82] Transubstantiality refers to the Sabellian heresy and to Leopold Bloom, Joyce in another body.

Consubstantiality, on Stephen's list of doctrines in "Telemachus", refers here to the view that Christ is both divine as God's Son and human as the Virgin Mary's. Stephen is spiritually consubstantial with Joyce, physically consubstantial with Simon Dedalus, a younger version of each.[91] "Subsubstantiality" refers to a Christ who lacks a human body. Stephen's list of heretics in "Telemachus" included Valentine, a Gnostic who held that the Son only appeared be made flesh, lacking a true body.[92] In "Oxen", Stephen illustrates by imagining a Virgin Mary who never gave birth.[90]

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the Virgin's womb is a metaphor for the imagination.[93] Stephen's first two doctrines allude to artistic re-embodiment, while the last alludes to its absence. "Subsubstantiality" characterizes the apparitions in "Circe", the next chapter. Hugh Kenner notes that "their detail tends to come from earlier in the book", forming "a sort of collective vocabulary out of which, it seems, anything at all can now be composed".[94] Ellmann calls them "the agitations and images of the unconscious mind"—"Joyce's version of the cruelty of the unconscious".[95] They are "phantoms of the past, memories recent or remote", not "works of art", because the imagination has created no "possible future" for them. The two exceptions are Stephen's dead mother and Bloom's dead son: "through a process of gestation ... they emerge as new creatures". Each is "an unforeseen blend of memory and imagination".[96] Not to say that the subsubstantial apparitions in "Circe" have no effect. Kenner compares them to "a psychoanalysis without an analyst"—a "catharsis". Bloom seems to have become "courageous, ready of mind": the "rummaging amid the roots of his secret fears and desires has brought forth a new self-possession". Hamlet-like Stephen emerges as a "man of action".[97] His rebellion's physical expression has been prefigured in earlier apparitions casting him in the role of black mass celebrant.[98]

Both the ghost of Stephen's dead mother and that of Bloom's dead son have been taken as epiphanies.[99] A composite of the Baptism of Christ and the Transfiguration is Joyce's actual source for the concept.[100] Stephen's epiphany both parallels and inverts these events. The Father's consubstantiality with Christ is manifested, Christ becoming radiant, and the Holy Ghost appears, the Father's voice addressing his son. In "Circe", the ghost of Stephen's mother identifies him as her son and he turns "white". But while the Father is "well-pleased" with his son, Stephen's mother is very disappointed in hers. The baptism marks the beginning of Christ's future on earth, his mission of suffering, death, and resurrection. Stephen's mother urges him to "Repent", to return to the faith he has rejected.

The epiphany then juxtaposes Christ's sacrifice and Satan's defiance, the one imaging Stephen's guilt, the other his desire to live and create freely. Stephen refuses to return to the Church, citing "the intellectual imagination"—his artistic mission—and using Satan's words, non serviam. The mother in turn uses language that identifies her with Christ, making mother and son archetypal adversaries. Stephen's lamp-smashing gives physical form to his rejection of Catholicism and initiates a future of his own choosing.[101]

Stephen's epiphany brought his mother back from the grave. Bloom's is a fleeting resurrection of his dead son. Rudy is an idealized image of his son had he lived to eleven,[102] an image that bears resemblance to Stephen.[103] Hugh Kenner doubts that Bloom sees Rudy, but allows that the apparition reflects Bloom's paternal feelings for Stephen.[104] That Rudy appears to be reading a Hebrew prayer book recalls Bloom's reminder in "Cyclops" that Christ was a Jew. The "white lambkin" identifies him as paschal victim, the resurrected Christ.[102] Bloom speaks his name in recognition of their consubstantiality. A little earlier he called out Stephen's name, twice. The unconscious Stephen is also Christ now, crucified by a soldier—his arms outstretched, "no bones broken",[105] his ashplant symbolizing the Cross.[102] Prostate, he awaits resurrection. Bloom's solicitousness signifies his "adoption" of Stephen, as Arius heretically characterized the Father-Son relation.[84] [106] The Arians also believed that the Son could complete his mission only with the Father's help.[107] Bloom's imaginary raising of his dead son is a prelude to his getting Stephen back on his feet.

In "Ithaca", Bloom is said to be the "transubstantial heir" of his parents and Stephen the "consubstantial heir" of his. Like the Sabellian Christ, Bloom is both a son and a father, while Stephen, like the consubstantial Christ, is only a son. The theological terms are a late reminder of Joyce's double presence in Ulysses. Bloom is his "transubstantial heir", the mature Joyce reincarnated, and Stephen his "consubstantial heir", a portrait of the artist as a young man.[108]

Joyce and the Eucharistedit

Although Catholicism was a resource for Joyce, he felt animosity toward it as a belief system. According to Christopher Hitchens, "Holy Mother Church was Joyce's lifelong enemy."[109] On 29 August 1904, he wrote to Nora: "Six years ago I left the Catholic Church hating it most fervently. I found it impossible to remain in it on account of the impulses of my nature. ... Now I make open war upon it by what I write and say and do."[110] In January 1904, in his essay "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man", Joyce said he had abandoned "open warfare" with the Church for what he called "urbanity in warfare",[111] which Richard Ellmann takes to mean "obliquity".[112] In "Ireland, Isle of Saints and Sages", a lecture he gave in Trieste in 1907, Joyce said, "I confess that I do not see what good it does to fulminate against the English tyranny while the Roman tyranny occupies the place of the soul."[113]

Joyce obliquely attacked the Church in his first short story, "The Sisters", published in 1904, a revised version of which begins Dubliners. As the Church's central sacrament, the Eucharist was his primary target. In Catholicism, "Eucharist" refers both to the act of Consecration, or transubstantiation, and its product, the body and blood of Christ under the appearances of bread and wine.[114] The wine is consecrated in a chalice, from which the priest drinks.[115] In "The Sisters", Father Flynn is said to have dropped his chalice, which "contained nothing", a way of saying that the spilt wine had not been changed into the blood of Christ.[116] Flynn's "empty" chalice contradicts the doctrine of the Eucharist.[117]

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce's war with the Church becomes more overt. Stephen Dedalus, Joyce's alter ego, rejects the Eucharist outright. He cannot be the artist he wants to be and remain in the Church. One of its rules enables him to dramatize his apostasy. He refuses to take Communion during Easter time, as is every Catholic's duty,[118] to show he is one no longer. The Eucharist is also useful as "a symbol behind which are massed twenty centuries of authority and veneration". Stephen parallels the literary artist with the Catholic priest and literary art with the Eucharist, both the act and the product. He sees himself as "The priest of eternal imagination transmuting the daily bread of experience into the radiant body of everliving life." The Eucharist has been wholly replaced by art.[119]

With Ulysses, Joyce returned to "open warfare" upon the Catholic Church. Writing in America magazine in 1934, the Jesuit Francis X. Talbot vehemently decried Judge Woolsey's recent decision that Ulysses was not obscene, adding, "Only a person who had been a Catholic, only one with an incurably diseased mind, could be so diabolically venomous toward God, toward the Blessed Sacrament, toward the Virgin Mary."[120] Joyce might have agreed that only a person who had been a Catholic could have written Ulysses. In it, he parodies Catholic elements and parallels them with other entities and activities. Joyce said to Frank Budgen, "Among other things, my book is the epic of the body."[121] One Joyce critic, a Jesuit priest, has defined transubstantiation as follows: "Through the divine power, Christ, as it were, comes across ('trans') the void to replace the substance of the bread, though the accidents (or appearances) of bread remain."[122] The same would hold true for the substance of the wine. Transubstantiation as replacement best characterizes Joyce's continuing attack on the Eucharist. In Ulysses, the illusion of body and blood is replaced by the real thing.[123]

Buck Mulligan's given name is Malachi, which means "messenger". Hugh Kenner has noted that in Ulysses Mulligan "introduces one theme after theme".[124] The first theme he introduces is the Eucharist, which, as William York Tindall has said, "becomes the central symbol of Ulysses".[125] The novel begins with a parody of the Eucharist. The setting is the Martello tower, where Stephen has been staying with Mulligan and Haines, an Englishman.

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him on the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned:

—Introibo ad altare Dei

—For this, O dearly beloved, is the genuine Christine: body and soul and blood and ouns.

The liturgical items and actions represented have been identified, if not uniformly.[126][127][128] The most obvious correspondence is between Mulligan's shaving bowl and the chalice of wine to be changed into the blood of Christ. That the shaving implements are crossed is a reminder that the Eucharist is meant to be the crucified Christ. Stephen reacts to Mulligan's performance by thinking of him as "Chrysostomos", a Greek Orthodox priest and the author of a liturgy. (The Greek Orthodox also believe in the doctrine of transubstantiation.) Mulligan's razor represents the knife the Greek priest uses to cut the bread to be consecrated.[129] The mirror corresponds to the small metal plate which holds the host to be consecrated. Mulligan's dressinggown corresponds to the vestments the priest wears at Mass. Kenner has noted that Mulligan is naked under his "ungirdled" gown.[130] In the Mass, the priest elevates the Eucharist so it can be adored. As Mulligan elevates his mock chalice, his genitals are exposed. Catholics believe that Christ is in both the priest and the Eucharist at the moment of Consecration. Mulligan is as much host as he is celebrant.

The Latin is the first line the priest speaks in the Mass. (In 1904, it was still said in Latin.) The parody's most striking feature is the change to the words of transubstantiation, "This is my body" and "This is the chalice of my blood."

—For this, O dearly beloved, is the genuine Christine: body and soul and blood and ouns.

As he did in "The Sisters", the first Dubliners story, Joyce has replaced the Latin rite with a "homely simulacrum".[131] Father Flynn's chalice "contained nothing", an illusory Christ, while Mulligan's holds the genuine Christine, a flesh and blood replacement. Mulligan's parody sets the tone for the treatment of the Eucharist throughout the novel. Equating a female Christ with the consecrated wine establishes the role Dublin women will play.[132]

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen calls Catholicism an "absurdity", and in Ulysses Leopold Bloom proves him right.[133] Bloom attends two Catholic rituals: a Mass in "Lotus Eaters" and a funeral in "Hades". His ignorance of liturgy shows in his descriptions of it. At the beginning of the funeral service, "The priest took a stick with a knob at the end of it out of the boy's bucket and shook it over the coffin." Kenner notes, "The description of the Holy Water being sprinkled gains its grotesque effect from Bloom's innocence."[134] So does the description of Communion: "A batch knelt at the altarrails. The priest went along by them, murmuring, holding the thing in his hands. He stopped at each, took out a communion, shook a drop or two (are they in water?) off it and put it neatly into her mouth."

In Trieste, Joyce attended the Byzantine rite. John McCourt writes that Joyce "drew on his own experience as an outsider, a spectator and observer at the Greek liturgies in Trieste, when writing about Leopold Bloom attending the Catholic mass ... and later a funeral".[135] Under the influence of the Greek rite Joyce revised his first version of "The Sisters",[131] and he rendered the Good Friday liturgy in Stephen Hero.[136] Bloom's description of Communion resembles Joyce's description of what he mistakenly thought was communion in the Greek rite: "a boy comes running down the side of the chapel with a large tray full of little lumps of bread. The priest comes after him and distributes the lumps to scrambling believers." (This bread is not consecrated, but is taken from the same loaf as the bread that is.[137])

Unfamiliar with the Greek liturgy, Joyce had no reason to doubt that the bread being distributed was consecrated. Unfamiliar with the Catholic Mass, Bloom has no reason to think that the bread and wine are supposed be other than what they appear to be. An informed believer would doubt his senses and imagine the body and blood of Christ. Bloom sees only bread and wine.

According to Kenner, "Description without knowledge is always potentially comic."[138] Moreover, Bloom's ignorance frees his imagination to create further comedy. (Kenner argues that Bloom's "periphrasis" is comic in itself.[138])

The priest bent down to put it into her mouth, murmuring all the time. Latin. The next one. Shut your eyes and open your mouth. What? Corpus: body. Corpse. Good idea the Latin. Stupefies them first. Hospice for the dying. They don't seem to chew it: only swallow it down. Rum idea: eating bits of a corpse. Why the cannibals cotton to it.

The priest was rinsing out the chalice: then he tossed off the dregs smartly. Wine. Makes it more aristocratic than for example if he drank what they are used to Guinness's porter or some temperance beverage Wheatley's Dublin hop bitters or Cantrell and Cochrane's ginger ale (aromatic). Doesn't give them any of it: shew wine: only the other. Cold comfort. Pious fraud but quite right: otherwise they'd have one old booser worse than another coming along, cadging for a drink. Queer the whole atmosphere of the. Quite right. Perfectly right that is.

Catholic communicants receive the consecrated bread as a wafer, hence "bits of a corpse". Only the priest receives wine: "Doesn't give them any of it." McCourt sees Bloom's thought about the Latin rite, "Queer the whole atmosphere", as very similar to Joyce's feeling that "the Greek mass is strange".[139] Calling the Eucharist a "pious fraud" would be an act of "open warfare" against the Church were it Joyce rather than Bloom.

On the Sandymount strand in "Nausicaa", Bloom encounters the Eucharist again. A Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament is taking place in a nearby church dedicated to Our Lady as Star of the Sea. Blamires has detailed the parallels between Gerty MacDowell and the Virgin Mary. He also notes that both the Virgin and the Eucharist are being adored in the church.[140] The Mirus bazaar, where the fireworks are launched, is linked to the bazaar in "Araby".[141] Like Mangan's sister in "Araby",[142] Gerty conflates them into a single sexual object of worship.

For Joyce, the "eternal qualities were the imagination and the sexual instinct".[143] He regarded "the individual passion as the motive power of everything"[144] and upheld the reality of the "sexual department" against the fiction of "spiritual love".[145] At the Benediction, the Eucharist is exposed to view so it can be adored. Gerty exposes herself to Bloom to sexually excite him, creating another object of worship. Bloom is touching his erect penis while the priest has the Eucharist "in his hands".[146]

Joyce owned the first (1910) German edition of Freud's Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, in which Freud asserts that "official religions" both exploited and denied "sexual activity" and that "originally the genitals as the pride and hope of living beings ... were worshiped as gods".[147] In "Nausicaa", all concerned raise their eyes to the adored object. The men at the benediction look up at the Eucharist. Bloom looks up along Gerty's legs and thighs toward her vagina. Gerty looks up at "a long Roman candle", which Bloom will connect with his penis: "Up like a rocket, down like a stick."[148]

Bloom has mistaken the Benediction for a Mass. ("Mass seems to be over", he says to himself later. At the time Mass was not celebrated in the evening.[149]) Writing for America magazine nearly 90 years after the irate Jesuit, a more moderate Catholic is tolerant of Bloom's ignorance of Church ritual, even when he misunderstands the Eucharist itself. But her tolerance would be tested in this case.[150] Bloom's mistaken idea that the benediction is a Mass allows a parallel between his orgasm and the act of transubstantiation that occurs during Mass. His masturbation caricatures the Catholic belief that Christ himself has his body in his hands at the Consecration of the bread.

Bloom reflects that he's glad he didn't masturbate in the bath ("Lotus Eaters"). His bathing corresponds to the Lavabo, the priest's ritual washing of his hands to prepare for the transubstantiation of the bread.[151] He did speak the words of Consecration, "This is my body." The act itself has been delayed till now. In the Mass the Elevation of the Eucharist follows the Consecration. Human physiology demands that Bloom's penis be elevated first.

The words of Consecration come at the end of the Eucharistic prayer. The prayer for Holy Thursday begins with a reference to the Last Supper: Christ, "on the day before He suffered, took bread into His holy and venerable hands." Bloom is touching himself. (Gerty thinks of him as "a man of inflexible honour to his fingertips".) The prayer continues, "and Christ having raised His eyes to heaven". Gerty bends so far back she trembles. Bloom "had a full view high up above her knee where no-one ever not even on the swing or wading and she wasn't ashamed and he wasn't either to look in that immodest way like that because he couldn't resist the sight of the wondrous revealment". (Her knickers are made of "nainsook", "a fine soft cotton fabric. It is a Hindi word that translates as 'eyes' delight".)

Gerty also masturbates and her orgasm also parallels the act of transubstantiation. Christ himself has the chalice of his blood in his hands at the Consecration of the wine ("This is the chalice of my blood ... which will be poured out for you"). Blamires calls Gerty "a 'vessel' now holding the blood soon to be spilt".[152] Elevation also precedes Consecration. Premenstrual Gerty "leaned back far to look up where the fireworks were and she caught her knee in her hands so as not to fall back looking up". The fireworks climax as both Bloom and Gerty do: "and O! then the Roman candle burst and it was like a sigh of O! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures ... O so lovely, O, soft, sweet, soft!"[153] Blamires has noted that Gerty experiences "imaginary consummation",[154] but her orgasm is real:[155][156] "As she leans further and further backward, ostensibly to view the Roman candles overhead, she is 'trembling in every limb' and the pressure of her 'nainsook knickers, the fabric that caresses the skin,' contributes to an orgasm that mimics the bursts of color rising in the evening sky."[157]

Mulligan feminized the Eucharist at the beginning of Ulysses with his Consecration parody. Gerty is the novel's first manifestation of "the genuine Christine". She prefigures Molly Bloom on her chamberpot.[158] When Gerty has gone, Bloom thinks, "Near her monthlies, I expect." At the Consecration, Catholics believe, bread and wine are replaced by the body and blood of Christ, appearances notwithstanding. In "Nausicaa", Christ's imagined body is replaced by real human flesh, his imagined blood by real human blood.[159] That orgasm has supplanted transubstantiation through masturbation, forbidden by the Church, completes Joyce's triumph over it.

Like Joyce, Satanists and Protestants have waged open war on the Catholic Church and made the Eucharist their primary target. The former believe in transubstantiation, but seek to desecrate its product.[160] The latter deny that the consecrated bread and wine are the body and blood of Christ. The climax of "Circe" is an apparitional black mass celebrated by a Satanic priest with the help of a Protestant minister. Stephen Dedalus and the Englishman Haines were witnesses to Mulligan's mockery of the Eucharist at the beginning of the novel ("This is . . . the genuine Christine"). Stephen's unconscious embellishes it, with versions of Mulligan and Haines as participants.

On an eminence, the centre of the earth, rises the fieldaltar of Saint Barbara. Black candles rise from its gospel and epistle horns. From the high barbacans of the tower two shafts of light fall on the smokepalled altarstone. On the altarstone Mrs Mina Purefoy, goddess of unreason, lies, naked, fettered, a chalice resting on her swollen belly. Father Malachi O'Flynn in a lace petticoat and reversed chasuble, his two left feet back to the front, celebrates camp mass. The Reverend Mr Hugh C Haines Love M. A. in a plain cassock and mortarboard, his head and collar back to the front, holds over the celebrant's head an open umbrella.

The black mass was celebrated on a woman's naked body.[161] The pregnant Mrs Purefoy, in labor for three days, is from "Oxen of the Sun". Father Malachi O’Flynn conflates Malachi Mulligan with Father O'Flynn, a Catholic priest from "Lestrygonians". (The black mass required an ordained priest to perform the act of transubstantiation.[162]) The Reverend Mr Haines Love conflates the Englishman Haines with the Protestant clergyman Hugh C Love from "Wandering Rocks". O'Flynn's "lace petticoat" indicates a gender inversion, which along with the anatomical and sartorial inversions signifies the central black mass reversal: "Satan is worshiped and Jesus Christ is cursed."[163]

In "Telemachus", Mulligan quotes the first words of the Mass, Introibo ad altare dei. Here they are altered for a black mass:

FATHER MALACHI O'FLYNN: Introibo ad altare diaboli.

THE REVEREND MR HAINES LOVE: To the devil which hath made glad my young days.

FATHER MALACHI O'FLYNN: (Takes from the chalice and elevates a blooddripping host.) Corpus meum.

THE REVEREND MR HAINES LOVE: (Raises high behind the celebrant's petticoat, revealing his grey bare hairy buttocks between which a carrot is stuck.) My body.

By lifting O'Flynn’s "lace petticoat" as transubstantiation is enacted, The Reverend Love is expressing the Protestant view that "my body" can be meant only literally. Kenner has noted that in "Telemachus" Mulligan is naked under his "ungirdled . . . dressinggown".[130] The anal carrot is an obvious phallic symbol, and the "way the Reverend Love reveals it under O'Flynn's petticoat suggests a homosexual relationship."[164] Among the black mass inversions is a sexual one.

In the black mass, "the abuse of the host seems to constitute the sacrifice to the devil".[165] O'Flynn's act of transubstantiation is simultaneously an act of desecration. His host is "blooddripping." Like Catholics, Satanists believe that the body of Christ is present in the host. Like Catholics guilty of the heresy of "sensualism", Satanists believe that the consecrated host gives direct contact with Christ's crucified body. Desecration can take the form of further torture.[166]

The Catholic belief that Christ is in both the consecrating priest and the Eucharist results in the desecration of O'Flynn's own body. That he has been feminized and sexualized in a parody of intercourse links him to Mrs Purefoy. In the medieval black mass a "woman was both altar and sacrifice".[167] An umbrella is used to protect the Eucharist during Catholic ceremonies.[168] The "open umbrella" held over O'Flynn is also symbolically a prophylactic. Her husband's use of one would have protected Mrs Purefoy from multiple pregnancies and painful childbirth. (That the Reverend Love is holding one open seems like a suggestion.) Mrs Purefoy is Catholicism's victim, "fettered" to the altar.[169] Not Christ but "the genuine Christine" is present in O'Flynn's continuously tortured host.[170]

In "Proteus", Stephen reflects on the fact that the Eucharist is in several places at once:

And at the same instant perhaps a priest round the corner is elevating it. Dringdring! And two streets off another locking it into a pyx. Dringadring! And in a ladychapel another taking housel all to his own cheek. Dringdring! Down, up, forward, back.

Ellmann has linked Stephen's reflection to Bloom's thoughts in "Nausicaa" on "the same identity-variety in the process of menstruation."[171]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Ulysses_(novel)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk