A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Valencia

València (Valencian) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

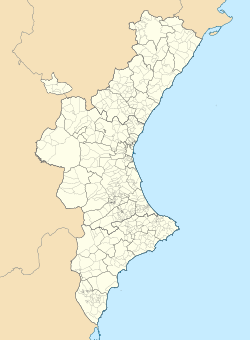

Location of Valencia | |

| Coordinates: 39°28′12″N 00°22′35″W / 39.47000°N 0.37639°W | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous Community | Valencian Community |

| Province | Valencia |

| Comarca | Horta of Valencia |

| Founded | 138 BC |

| Districts | 19 districtes

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Ayuntamiento/Ajuntament |

| • Body | Ajuntament de València |

| • Mayor | María José Catalá (since 2023) (PP) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 134.65 km2 (51.99 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 628.81 km2 (242.78 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Population (2023)[4] | |

| • Municipality | 807,693[1] |

| • Density | 5,998.5/km2 (15,536/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,595,000[3] |

| • Metro | 2,522,383[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Valencian •valencià, -ana (va) •valenciano, -na (es) |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | €56.413 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET (GMT)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST (GMT)) |

| Postcode | 46000-46080 |

| ISO 3166-2 | ES-V |

| Website | www.valencia.es |

Valencia (Spanish: [baˈlenθja] , officially in Valencian: València [vaˈlensia])[a] is the capital of the province and autonomous community of the same name. It is the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 807,693 inhabitants (2023) within the Ciudad de Valencia[1] and 1,582,387 inhabitants (2021) within metropolis of the Huerta de Valencia.[6][7] It is located in eastern Spain, on the banks of the Turia, on the east coast of the Iberian Peninsula on the Mediterranean Sea.

Valencia was founded as a Roman colony in 138 BC under the name Valentia Edetanorum. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Valencia became part of the Visigothic Kingdom from 546 AC and 711 AC. Islamic rule and acculturation ensued in the 8th century, together with the introduction of new irrigation systems and crops. Aragonese Christian conquest took place in 1238, and so the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Valencia. The city's population thrived in the 15th century, owing to trade with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Italian ports, and other Mediterranean locations, becoming one of the largest European cities by the end of the century. Already harmed by the emergence of the Atlantic World trade in detriment to Mediterranean trade in global trade networks, along with insecurity created by Barbary piracy throughout the 16th century, the city's economic activity experienced a crisis upon the expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609. The city became a major silk manufacturing centre in the 18th century. During the Spanish Civil War, the city served as the accidental seat of the Spanish Government from 1936 to 1937.[8]

The Port of Valencia is the 5th-busiest container port in Europe and the second busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea. The city is ranked as a Gamma-level global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[9] Its historic centre is one of the largest in Spain, spanning approximately 169 hectares (420 acres).[10] Due to its long history, Valencia has numerous celebrations and traditions, such as the Falles (or Fallas), which was declared a Fiesta of National Tourist Interest of Spain in 1965[11] and an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in November 2016. In 2022, the city was voted the world's top destination for expatriates, based on criteria such as quality of life and affordability.[12][13] The city was selected as the European Capital of Sport 2011, the World Design Capital 2022 and the European Green Capital 2024.

Name

The Latin name of the city was Valentia (IPA: [waˈlɛntɪ.a]), meaning "strength" or "valour", due to the Roman practice of recognising the valour of former Roman soldiers after a war. The Roman historian Livy explains that the founding of Valentia in the 2nd century BC was due to the settling of the Roman soldiers who fought against a Lusitanian rebel, Viriatus, during the Third Raid of the Lusitanian War.[14]

During the period of Islamic rule, the city had the title Medina at-Tarab ('City of Joy') according to one transliteration, or Medina at-Turab ('City of Sands') according to another, since it was located on the banks of the River Turia. It is not clear if an Arabised variant of the Latin name (Balansiyya) was reserved for the wider Taifa of Valencia, or also designated the city.[15]

Via gradual phonetic changes, Valentia became Valencia [baˈlenθja] in Spanish and València [vaˈlensia] in Valencian. In Valencian, an e with a grave accent (è) indicates [ɛ] in contrast to [e], but the word València is an exception to this rule, since è is pronounced [e]. The spelling "València" was approved by the AVL based on tradition after a debate on the matter. The name "València" has been the only official name of the city since 2017.[16] In 2023, the Commission of Culture of the municipal corporation agreed in principle on a dual official denomination Valencia / Valéncia, with the far right managing to impose[editorializing] a non-standard acute accent in the e of the Valencian-language name.[17][18]

History

Roman colony

Valencia is one of the oldest cities in Spain, founded in the Roman period c. 138 BC under the name Valentia Edetanorum.[19] A few centuries later, with the power vacuum left by the demise of the Roman imperial administration, the Catholic Church assumed power in the city, coinciding with the first waves of the invading Germanic peoples (Suebi, Vandals, Alans, and later Visigoths).

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Valencia became part of the Visigothic Kingdom from 546 AC and 711 AC.[20] The city surrendered to the invading Moors about 714 AD.[21] Abd al-Rahman I laid waste to old Valencia by 788–789.[22] From then on, the name of Valencia (Arabised as Balansiya) appears more related to the wider area than to the city, which is primarily cited as Madînat al-Turâb ('city of earth' or 'sand') and presumably had diminished importance throughout the period.[23] During the emiral period, the surrounding territory, under the ascendancy of Berber chieftains, was prone to unruliness.[24] In the wake of the start of the fitna of al-Andalus, Valencia became the head of an independent emirate, the Taifa of Valencia.[25] It was initially controlled by eunuchs,[25] and then, after 1021, by Abd al-Azîz (a grandson of Almanzor).[26] Valencia experienced notable urban development in this period.[27] Many Jews lived in Valencia, including the accomplished Jewish poet Solomon ibn Gabirol, who spent his last years in the city.[28] After a damaging offensive by Castilian–Leonese forces towards 1065, the territory became a satellite of the Taifa of Toledo, and following the fall of the latter in 1085, a protectorate of "El Cid". A revolt erupted in 1092, handing the city to the Almoravids and forcing El Cid to take the city by force in 1094, henceforth establishing his own principality.[29]

Following the evacuation of the city in 1102, the Almoravids took control. As the Almoravid empire crumbled in the mid 12th-century, ibn Mardanīsh took control of eastern al-Andalus, creating a Murcia-centered independent emirate to which Valencia belonged, resisting the Almohads until 1172.[30] During the Almohad rule, the city perhaps had a population of about 20,000.[31] When the city fell to James I of Aragon, the Jewish population constituted about 7 per cent of the total population.[28]

In 1238,[32] King James I of Aragon, with an army composed of Aragonese, Catalans, Navarrese, and crusaders from the Order of Calatrava, laid siege to Valencia and on 28 September obtained a surrender.[33] Fifty thousand Moors were forced to leave.[citation needed]

The city endured serious troubles in the mid-14th century, including the decimation of the population by the Black Death of 1348 and subsequent years of epidemics—as well as a series of wars and riots that followed. In 1391, the Jewish quarter was destroyed in a pogrom.[28]

Genoese traders promoted the expansion of the cultivation of white mulberry in the area by the late 14th century, and later introduced innovative silk manufacturing techniques. The city became a centre of mulberry production and was, at least for a time, a major silk-making centre.[34] The Genoese community in Valencia—merchants, artisans and workers—became, along with Seville's, one of the most important in the Iberian Peninsula.[35]

In 1407, following the model of the Barcelona's institution created some years before, a Taula de canvi (a municipal public bank) was created in Valencia, although its first iteration yielded limited success.[36]

The 15th century was a time of economic expansion, known as the Valencian Golden Age, during which culture and the arts flourished. Concurrent population growth made Valencia the most populous city in the Crown of Aragon. Some of the landmark buildings of the city were built during the Late Middle Ages, including the Serranos Towers, the Silk Exchange, the Miguelete Tower, and the Chapel of the Kings of the Convent of Sant Domènec. In painting and sculpture, Flemish and Italian trends had an influence on Valencian artists.

Valencia became a major slave trade centre in the 15th century, second only to Lisbon in the West,[37] prompting a Lisbon–Seville–Valencia axis by the second half of the century powered by the incipient Portuguese slave trade originating in West Africa.[38] By the end of the 15th century Valencia was one of the largest European cities, being the most populated city in the Hispanic Monarchy and second to Lisbon in the Iberian Peninsula.[39]

Modern history

Following the death of Ferdinand II in 1516, the nobiliary estate challenged the Crown amid the relative void of power.[40] In 1519, the Taula de Canvis was recreated again, known as Nova Taula.[41] The nobles earned the rejection from the people of Valencia, and the whole kingdom was plunged into the armed Revolt of the Brotherhoods and full-blown civil war between 1521 and 1522.[40] Muslim vassals were forced to convert in 1526 at the behest of Charles V.[40]

Urban and rural delinquency—linked to phenomena such as vagrancy, gambling, larceny, pimping and false begging—as well as the nobiliary banditry consisting of the revenges and rivalries between the aristocratic families flourished in Valencia during the 16th century.[42]

Also during the 16th century, North African piracy targeted the whole coastline of the kingdom of Valencia, forcing the fortification of sites.[43] By the late 1520s, the intensification of Barbary corsair activity along with domestic conflicts and the emergence of the Atlantic Ocean in detriment of the Mediterranean in global trade networks put an end to the economic splendor of the city.[44] The piracy also paved the way for the ensuing development of Christian piracy, that had Valencia as one of its main bases in the Iberian Mediterranean.[43] The Berber threat—initially with Ottoman support—generated great insecurity on the coast, and it would not be substantially reduced until the 1580s.[43]

The crisis deepened during the 17th century with the 1609 expulsion of the Moriscos, descendants of the Muslim population that had converted to Christianity. The Spanish government systematically forced Moriscos to leave the kingdom for Muslim North Africa. They were concentrated in the former Crown of Aragon, and in the Kingdom of Valencia specifically, and constituted roughly a third of the total population.[45] The expulsion caused the financial ruin of some of the Valencian nobility and the bankruptcy of the Taula de canvi in 1613.

The decline of the city reached its nadir with the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1709), marking the end of the political and legal independence of the Kingdom of Valencia. During the War of the Spanish Succession, Valencia sided with the Habsburg ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, Charles of Austria. King Charles of Austria vowed to protect the laws (Furs) of the Kingdom of Valencia, which gained him the sympathy of a wide sector of the Valencian population. On 24 January 1706, Charles Mordaunt, 3rd Earl of Peterborough, 1st Earl of Monmouth, led a handful of English cavalrymen into the city after riding south from Barcelona, captured the nearby fortress at Sagunt, and bluffed the Spanish Bourbon army into withdrawal.

The English held the city for 16 months and defeated several attempts to expel them. After the victory of the Bourbons at the Battle of Almansa on 25 April 1707, the English army evacuated Valencia and Philip V ordered the repeal of the Furs of Valencia as punishment for the kingdom's support of Charles of Austria.[46] By the Nueva Planta decrees, the ancient Charters of Valencia were abolished and the city was governed by the Castilian Charter, similarly to other places in the Crown of Aragon.

The Valencian economy recovered during the 18th century with the rising manufacture of woven silk and ceramic tiles. The silk industry boomed during this century, with Valencia replacing Toledo as the main silk-manufacturing centre in Spain.[34] The Palau de Justícia is an example of the affluence manifested in the most prosperous times of Bourbon rule (1758–1802) during the rule of Charles III. The 18th century was the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, and its humanistic ideals influenced men such as Gregory Maians and Pérez Bayer in Valencia, who maintained correspondence with the leading French and German thinkers of the time.

Peninsular War

The 19th century began with Spain embroiled in wars with France, Portugal, and England—but the Peninsular War (Spanish War of Independence) most affected the Valencian territories and the capital city. The repercussions of the French Revolution were still felt when Napoleon's armies invaded the Iberian Peninsula. The Valencian people rose up in arms against them on 23 May 1808, inspired by leaders such as Vicent Doménech el Palleter.[citation needed]

The mutineers seized the Citadel, the Supreme Junta government took over, and on 26–28 June, Napoleon's Marshal Moncey attacked the city with a column of 9,000 French imperial troops in the First Battle of Valencia. He failed to take the city in two assaults and retreated to Madrid. Marshal Suchet began a long siege of the city in October 1811, and after intense bombardment forced it to surrender on 8 January 1812. After Valencian capitulation, the French instituted reforms in Valencia, which became the capital of Spain when the Bonapartist pretender to the throne, José I (Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's elder brother), moved the Court there in the middle of 1812. The disaster of the Battle of Vitoria on 21 June 1813 obliged Suchet to quit Valencia, and the French troops withdrew in July.

Post-war

Ferdinand VII became king after the victorious end of the Peninsular War, which freed Spain from Napoleonic domination. When he returned on 24 March 1814 from exile in France, the Cortes requested that he respect the liberal Constitution of 1812, which significantly limited royal powers. Ferdinand refused and went to Valencia instead of Madrid. Here, on 17 April, General Elio invited the King to reclaim his absolute rights and put his troops at the King's disposition. The king abolished the Constitution of 1812 and dissolved the two chambers of the Spanish Parliament on 10 May. Thus began six years (1814–1820) of absolutist rule, but the constitution was reinstated during the Trienio Liberal, a period of three years of liberal government in Spain from 1820 to 1823.

On King Ferdinand VII's death in 1833, Baldomero Espartero became one of the most ardent defenders of the hereditary rights of the king's daughter, the future Isabella II. During the regency of Maria Cristina, Espartero ruled Spain for two years as its 18th Prime Minister from 16 September 1840 to 21 May 1841. City life in Valencia carried on in a revolutionary climate, with frequent clashes between liberals and republicans.

The reign of Isabella II as an adult (1843–1868) was a period of relative stability and growth for Valencia. During the second half of the 19th century the bourgeoisie encouraged the development of the city and its environs; land-owners were enriched by the introduction of the orange crop and the expansion of vineyards and other crops. This economic boom corresponded with a revival of local traditions and of the Valencian language, which had been ruthlessly suppressed from the time of Philip V.

Work to demolish the walls of the old city started on 20 February 1865.[47] The demolition of the citadel ended after the 1868 Glorious Revolution.[47]

During the Cantonal rebellion in 1873, Valencia was the capital of the short-lived Valencian Canton.[48]

Following the introduction of universal manhood suffrage in the late 19th century, the political landscape in Valencia—until then consisting of the bipartisanship characteristic of the early Restoration period—experienced a change, leading to a growth of republican forces, gathered around the emerging figure of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez.[49] Not unlike the equally republican Lerrouxism, the Populist Blasquism came to mobilize the Valencian masses by promoting anticlericalism.[50] Meanwhile, in reaction, the right-wing coalesced around several initiatives such as the Catholic League or the reformulation of Valencian Carlism, and Valencianism did similarly with organizations such as Valencia Nova or the Unió Valencianista.[51]

20th century

In the early 20th century, Valencia was an industrialised city. The silk industry had disappeared, but there was a large production of hides and skins, wood, metals, and foodstuffs, the latter with substantial exports, particularly of wine and citrus. Small businesses predominated, but with the rapid mechanisation of the industry, larger companies were being formed. The best expression of this dynamic was in regional exhibitions, including that of 1909 held next to the pedestrian avenue L'Albereda (Paseo de la Alameda), which depicted the progress of agriculture and industry. Among the most architecturally successful buildings of the era were those designed in the Art Nouveau style, such as the Estació del Nord and the Central and Columbus markets.

World War I (1914–1918) greatly affected the Valencian economy, causing the collapse of its citrus exports. The Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939) opened the way for democratic participation and the increased politicisation of citizens, especially in response to the rise of Conservative Front power in 1933. The inevitable march toward civil war and combat in Madrid resulted in the relocation of the capital of the Republic to Valencia.

After the continuous unsuccessful Francoist offensive on besieged Madrid during the Spanish Civil War, Valencia temporarily became the capital of Republican Spain on 6 November 1936. It hosted the government until 31 October 1937.[52]

Francoist Spain

In the Spanish civil war, Valencia was heavily bombarded by air and sea, mainly by the Fascist Italian air force, as well as the Francoist air force with Nazi German support. By the end of the war, the city had survived 442 bombardments, leaving 2,831 dead and 847 wounded, although it is estimated that the death toll was higher. The Republican government moved to Barcelona on 31 October of that year. On 30 March 1939, Valencia surrendered and Nationalist Spanish troops entered the city.

The postwar years were a time of hardship for Valencians. During Franco's regime, speaking or teaching Valencian was prohibited; in a significant reversal, it is now compulsory for every schoolchild in Valencia. Franco's dictatorship forbade political parties and began a harsh ideological and cultural repression countenanced and sometimes led by the Catholic Church. Franco's regime also executed some leading Valencian intellectuals, such as Juan Peset, rector of University of Valencia. Large groups of them, including Josep Renau and Max Aub, went into exile.

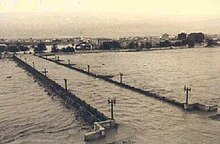

In 1943, Franco decreed the exclusivity of Valencia and Barcelona for the celebration of international fairs in Spain.[53] These two cities would hold the monopoly on international fairs for more than three decades, until the rule's abolishment in 1979 by the government of Adolfo Suárez.[53] In October 1957, a flood from the Turia river resulted in 81 casualties and extensive property damage.[54] The disaster led to the remodelling of the city and the creation of a new river bed for the Turia, with the old one becoming one of the city's "green lungs".[54] The economy began to recover in the early 1960s, and the city experienced explosive population growth through immigration spurred by jobs created with the implementation of major urban projects and infrastructure improvements.

Post-Franco

With the advent of democracy in Spain, the ancient kingdom of Valencia was established as a new autonomous entity, the Valencian Community, the Statute of Autonomy of 1982 designating Valencia as its capital. Valencia has since then experienced a surge in its cultural development, exemplified by exhibitions and performances at such iconic institutions as the Palau de la Música, the Palacio de Congresos, the Metro, the City of Arts and Sciences (Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències), the Valencian Museum of Enlightenment and Modernity (Museo Valenciano de la Ilustracion y la Modernidad), and the Institute of Modern Art (Institut Valencià d'Art Modern). The various productions of Santiago Calatrava, a renowned structural engineer, architect, and sculptor and of the architect Félix Candela have contributed to Valencia's international reputation. These public works and the ongoing rehabilitation of the "Old City" (Ciutat Vella) have helped improve the city's livability, and tourism is continually increasing.

21st century

On 3 July 2006, a major mass transit disaster, the Valencia Metro derailment, left 43 dead and 47 wounded.[55] Days later, on 9 July, the World Day of Families, during Mass at Valencia's Cathedral, Our Lady of the Forsaken Basilica, Pope Benedict XVI used the Sant Calze, a 1st-century Middle-Eastern artifact that some Catholics believe is the Holy Grail.[b]

Valencia was selected in 2003 to host the historic America's Cup yacht race, the first European city ever to do so. The 2007 America's Cup matches took place from April to July. On 3 July 2007, Alinghi defeated Team New Zealand to retain the America's Cup. Twenty-two days later, on 25 July 2007, the leaders of the Alinghi syndicate, holder of the America's Cup, officially announced that Valencia would be the host city for the 33rd America's Cup, held in June 2009.[57]

The results of the Valencia municipal elections from 1991 to 2011 delivered a 24-year uninterrupted rule (1991–2015) by the People's Party (PP) and Mayor Rita Barberá, with support from the Valencian Union. Barberá's rule was ousted by left-leaning forces after the 2015 municipal election, with Joan Ribó of Compromís becoming the new mayor.

Geography

Location

Located on the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula and the western part of the Mediterranean Sea, fronting the Gulf of Valencia, Valencia lies on the highly fertile alluvial silts accumulated on the floodplain formed in the lower course of the Turia River.[58] At its founding by the Romans in 138 BC, it stood on an alluvial plain of the Turia River several kilometers from the sea.[59]

The Albufera lagoon, located about 12 km (7 mi) south of the city proper (and part of the municipality), was originally a saltwater lagoon, but since the severing of links to the sea, it has eventually become a freshwater lagoon, progressively decreasing in size.[60] The lagoon and its environment are used for the cultivation of rice in paddy fields, and for hunting and fishing purposes.[60]

The Valencia City Council bought the lake from the Crown of Spain for 1,072,980 pesetas in 1911,[61] and today it forms the main portion of the Parc Natural de l'Albufera (Albufera Nature Reserve), with a surface area of 21,120 hectares (52,200 acres). Because of its cultural, historical, and ecological value, it was declared a natural park in 1976.

Climate

Valencia and its metropolitan area have a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) bordering on a semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh)[62][63] with mild winters and hot, dry summers.[64][65] According to the Siegmund/Frankenberg climate classification, Valencia has a subtropical climate.[66]

The average annual temperature of Valencia is 18.6 °C (65.5 °F); 23 °C (73 °F) during the day and 14.2 °C (57.6 °F) at night. In the coldest month, January, the maximum daily temperature typically ranges from 15 to 20 °C (59 to 68 °F), the minimum temperature typically at night ranges from 6 to 10 °C (43 to 50 °F). December, January and February are the coldest months, with average temperatures around 17 °C (63 °F) during the day and 8 °C (46 °F) at night. March is transitional, the temperature often exceeds 20 °C (68 °F), with an average temperature of 19.3 °C (66.7 °F) during the day and 10 °C (50 °F) at night. During the warmest months – July and August, the maximum temperature during the day typically ranges from 28 to 32 °C (82 to 90 °F), about 21 to 24 °C (70 to 75 °F) at night. In the summer months, humidity levels tend to be high (just like in many other seaside cities), which makes the weather feel stuffy and sticky, increasing the heat index. This makes the 30 °C (86 °F) in Valencia may seem hotter than those in inland cities like Madrid or Córdoba.[67]

The maximum of precipitation occurs in autumn, coinciding with the time of the year when cold drop (gota fría) episodes of heavy rainfall—associated to cut-off low pressure systems at high altitude—[68] are common along the Western mediterranean coast.[69] The year-on-year variability in precipitation may be, however, considerable.[69]

Snowfall is almost does not occur at all; the most recent occasion snow accumulated on the ground was on 11 January 1960.[70] Valencia has one of the mildest winters in Europe, owing to its southern location on the Mediterranean Sea and the Foehn phenomenon, locally known as ponentà.[71] The January average is comparable to temperatures expected for May and September in the major cities of northern Europe.[72]

The highest and lowest temperatures recorded in the city since 1937 were 44.7 °C (112.5 °F) on 10 August 2023 and −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) on 11 February 1956, respectively.[73]

Valencia, on average, has around 2,670 sunshine hours per year, from 152 in December (average of 5 hours of sunshine duration a day) to 308 in July (average around 10 hours of sunshine duration a day). The average temperature of the sea is 14–15 °C (57–59 °F) in winter and 25–26 °C (77–79 °F) in summer.[74][75] Average annual relative humidity is 65%.[76]

| Climate data for Valencia (normals and extremes 1991-2020), altitude: 11 m.a.s.l. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.6 (79.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

40.3 (104.5) |

43.0 (109.4) |

38.4 (101.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

23.0 (73.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

18.6 (65.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Valencia_(city_in_Spain)||||||||||