A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinitic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geographic distribution | China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguistic classification | Sino-Tibetan

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early forms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subdivisions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-5 | zhx | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | sini1245 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

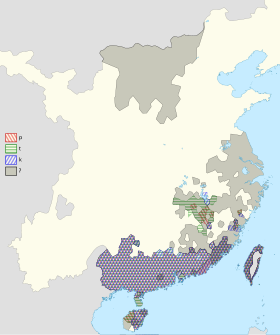

Primary branches of Chinese according to the Language Atlas of China.[3] The Mandarin area extends into Yunnan and Xinjiang (not shown). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hànyǔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han language | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

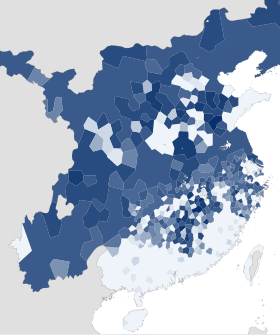

There are hundreds of local Chinese language varieties[b] forming a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast part of mainland China. The varieties are typically classified into several groups: Mandarin, Wu, Min, Xiang, Gan, Jin, Hakka and Yue, though some varieties remain unclassified. These groups are neither clades nor individual languages defined by mutual intelligibility, but reflect common phonological developments from Middle Chinese.

Chinese varieties have the greatest differences in their phonology, and to a lesser extent in vocabulary and syntax. Southern varieties tend to have fewer initial consonants than northern and central varieties, but more often preserve the Middle Chinese final consonants. All have phonemic tones, with northern varieties tending to have fewer distinctions than southern ones. Many have tone sandhi, with the most complex patterns in the coastal area from Zhejiang to eastern Guangdong.

Standard Chinese takes its phonology from the Beijing dialect, with vocabulary from the Mandarin group and grammar based on literature in the modern written vernacular. It is one of the official languages of China and one of the four official languages of Singapore. It has become a pluricentric language, with differences in pronunciation and vocabulary between the three forms. It is also one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

History

At the end of the 2nd millennium BC, a form of Chinese was spoken in a compact area along the lower Wei River and middle Yellow River. Use of this language expanded eastwards across the North China Plain into Shandong, and then southwards into the Yangtze River valley and the hills of south China. Chinese eventually replaced many of the languages previously dominant in these areas, and forms of the language spoken in different regions began to diverge.[7] During periods of political unity there was a tendency for states to promote the use of a standard language across the territory they controlled, in order to facilitate communication between people from different regions.[8]

The first evidence of dialectal variation is found in the texts of the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC). Although the Zhou royal domain was no longer politically powerful, its speech still represented a model for communication across China.[7] The Fangyan (early 1st century AD) is devoted to differences in vocabulary between regions.[9] Commentaries from the Eastern Han (25–220 AD) provide significant evidence of local differences in pronunciation. The Qieyun, a rime dictionary published in 601, noted wide variations in pronunciation between regions, and was created with the goal of defining a standard system of pronunciation for reading the classics.[10] This standard is known as Middle Chinese, and is believed to be a diasystem, based on a compromise between the reading traditions of the northern and southern capitals.[11]

The North China Plain provided few barriers to migration, which resulted in relative linguistic homogeneity over a wide area. Contrastingly, the mountains and rivers of southern China contain all six of the other major Chinese dialect groups, with each in turn featuring great internal diversity, particularly in Fujian.[12][13]

Standard Chinese

Until the mid-20th century, most Chinese people spoke only their local language. As a practical measure, officials of the Ming and Qing dynasties carried out the administration of the empire using a common language based on Mandarin varieties, known as Guānhuà (官話/官话 'officer speech'). While never formally defined, knowledge of this language was essential for a career in the imperial bureaucracy.[14]

In the early years of the Republic of China, Literary Chinese was replaced as the written standard by written vernacular Chinese, which was based on northern dialects. In the 1930s, a standard national language with pronunciation based on the Beijing dialect was adopted, but with vocabulary drawn from a range of Mandarin varieties, and grammar based on literature in the modern written vernacular.[15] Standard Chinese is the official spoken language of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan, and is one of the official languages of Singapore.[16] It has become a pluricentric language, with differences in pronunciation and vocabulary between the three forms.[17][18]

Standard Chinese is much more widely studied than any other variety of Chinese, and its use is now dominant in public life on the mainland.[19] Outside of China and Taiwan, the only varieties of Chinese commonly taught in university courses are Standard Chinese and Cantonese.[20]

Comparison with Romance

Chinese has been likened to the Romance languages that descended from Latin. In both cases, the ancestral language was spread by imperial expansion over substrate languages 2000 years ago, by the Qin and Han empires in China, and the Roman Empire in Europe. Medieval Latin remained the standard for scholarly and administrative writing in Western Europe for centuries, influencing local varieties much like Literary Chinese did in China. In both cases, local forms of speech diverged from both the literary standard and each other, producing dialect continua with mutually unintelligible varieties separated by long distances.[20][21]

However, a major difference between China and Western Europe is the historical reestablishment of political unity in 6th century China by the Sui dynasty, a unity that has persisted with relatively brief interludes until the present day. Meanwhile, Europe remained politically decentralized, and developed numerous independent states. Vernacular writing using the Latin alphabet supplanted Latin itself, and states eventually developed their own standard languages. In China, Literary Chinese was predominantly used in formal writing until the early 20th century. Written Chinese, read with different local pronunciations, continued to serve as a source of vocabulary for the local varieties. The new standard written vernacular Chinese, the counterpart of spoken Standard Chinese, is similarly used as a literary form by speakers of all varieties.[22][23]

Classification

Dialectologist Jerry Norman estimated that there are hundreds of mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese.[24] These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, although there are also some sharp boundaries.[25]

However, the rate of change in mutual intelligibility varies immensely depending on region. For example, the varieties of Mandarin spoken in all three northeastern Chinese provinces are mutually intelligible, but in the province of Fujian, where Min varieties predominate, the speech of neighbouring counties or even villages may be mutually unintelligible.[26]

Dialect groups

Classifications of Chinese varieties in the late 19th century and early 20th century were based on impressionistic criteria. They often followed river systems, which were historically the main routes of migration and communication in southern China.[28] The first scientific classifications, based primarily on the evolution of Middle Chinese voiced initials, were produced by Wang Li in 1936 and Li Fang-Kuei in 1937, with minor modifications by other linguists since.[29] The conventionally accepted set of seven dialect groups first appeared in the second edition (1980) of Yuan Jiahua's dialectology handbook:[30][31]

- Mandarin

- This is the group spoken in northern and southwestern China and has by far the most speakers. This group includes the Beijing dialect, which forms the basis for Standard Chinese, called Putonghua or Guoyu in Chinese, and often also translated as "Mandarin" or simply "Chinese". In addition, the Dungan language of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan is a Mandarin variety written in the Cyrillic script.

- Wu

- These varieties are spoken in Shanghai, most of Zhejiang and the southern parts of Jiangsu and Anhui. The group comprises hundreds of distinct spoken forms, many of which are not mutually intelligible. The Suzhou dialect is usually taken as representative, because Shanghainese features several atypical innovations.[32] Wu varieties are distinguished by their retention of voiced or murmured obstruent initials (stops, affricates and fricatives).[33]

- Gan

- These varieties are spoken in Jiangxi and neighbouring areas. The Nanchang dialect is taken as representative. In the past, Gan was viewed as closely related to Hakka because of the way Middle Chinese voiced initials became voiceless aspirated initials as in Hakka, and were hence called by the umbrella term "Hakka–Gan dialects".[34][35]

- Xiang

- The Xiang varieties are spoken in Hunan and southern Hubei. The New Xiang varieties, represented by the Changsha dialect, have been significantly influenced by Southwest Mandarin, whereas Old Xiang varieties, represented by the Shuangfeng dialect, retain features such as voiced initials.[36]

- Min

- These varieties originated in the mountainous terrain of Fujian and eastern Guangdong, and form the only branch of Chinese that cannot be directly derived from Middle Chinese. It is also the most diverse, with many of the varieties used in neighbouring counties—and, in the mountains of western Fujian, even in adjacent villages—being mutually unintelligible.[26] Early classifications divided Min into Northern and Southern subgroups, but a survey in the early 1960s found that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups.[37][38] Varieties from the coastal region around Xiamen have spread to Southeast Asia, where they are known as Hokkien (named from a dialectical pronunciation of "Fujian"), and Taiwan, where they are known as Taiwanese.[39] Other offshoots of Min are found in Hainan and the Leizhou Peninsula, with smaller communities throughout southern China.[38]

- Hakka

- The Hakka (literally "guest families") are a group of Han Chinese living in the hills of northeastern Guangdong, southwestern Fujian and many other parts of southern China, as well as Taiwan and parts of Southeast Asia such as Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. The Meixian dialect is the prestige form.[40] Most Hakka varieties retain the full complement of nasal endings, -m -n -ŋ and stop endings -p -t -k, though there is a tendency for Middle Chinese velar codas -ŋ and -k to yield dental codas -n and -t after front vowels.[41]

- Yue

- These varieties are spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong and Macau, and have been carried by immigrants to Southeast Asia and many other parts of the world. The prestige variety and by far most commonly spoken variety is Cantonese, from the city of Guangzhou (historically called "Canton"), which is also the native language of the majority in Hong Kong and Macau.[42] Taishanese, from the coastal area of Jiangmen southwest of Guangzhou, was historically the most common Yue variety among overseas communities in the West until the late 20th century.[43] Not all Yue varieties are mutually intelligible. Most Yue varieties retain the full complement of Middle Chinese word-final consonants (/p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/ and /ŋ/) and have rich inventories of tones.[41]

The Language Atlas of China (1987) follows a classification of Li Rong, distinguishing three further groups:[44][45]

- Jin

- These varieties, spoken in Shanxi and adjacent areas, were formerly included in Mandarin. They are distinguished by their retention of the Middle Chinese entering tone category.[46]

- Huizhou

- The Hui dialects, spoken in southern Anhui, share different features with Wu, Gan and Mandarin, making them difficult to classify. Earlier scholars had assigned to them one or other of these groups, or to a group of their own.[47][48]

- Pinghua

- These varieties are descended from the speech of the earliest Chinese migrants to Guangxi, predating the later influx of Yue and Southwest Mandarin speakers. Some linguists treat them as a mixture of Yue and Xiang.[49]

Some varieties remain unclassified, including the Danzhou dialect (northwestern Hainan), Mai (southern Hainan), Waxiang (northwestern Hunan), Xiangnan Tuhua (southern Hunan), Shaozhou Tuhua (northern Guangdong), and the forms of Chinese spoken by the She people (She Chinese) and the Miao people.[50][51][52] She Chinese, Xiangnan Tuhua, Shaozhou Tuhua and unclassified varieties of southwest Jiangxi appear to be related to Hakka.[53][54]

Most of the vocabulary of the Bai language of Yunnan appears to be related to Chinese words, though many are clearly loans from the last few centuries. Some scholars have suggested that it represents a very early branching from Chinese, while others argue that it is a more distantly related Sino-Tibetan language overlaid with two millennia of loans.[55][56][57]

Dialect geography

Jerry Norman classified the traditional seven dialect groups into three zones: Northern (Mandarin), Central (Wu, Gan, and Xiang) and Southern (Hakka, Yue, and Min).[63] He argued that the dialects of the Southern zone are derived from a standard used in the Yangtze valley during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), which he called Old Southern Chinese, while the Central zone was a transitional area of dialects that were originally of southern type, but overlain with centuries of Northern influence.[63][59] Hilary Chappell proposed a refined model, dividing Norman's Northern zone into Northern and Southwestern areas, and his Southern zone into Southeastern (Min) and Far Southern (Yue and Hakka) areas, with Pinghua transitional between Southwestern and Far Southern areas.[64]

The long history of migration of peoples and interaction between speakers of different dialects makes it difficult to apply the tree model to Chinese.[65] Scholars account for the transitional nature of the central varieties in terms of wave models. Iwata argues that innovations have been transmitted from the north across the Huai River to the Lower Yangtze Mandarin area and from there southeast to the Wu area and westwards along the Yangtze River valley and thence to southwestern areas, leaving the hills of the southeast largely untouched.[66]

Some dialect boundaries, such as between Wu and Min, are particularly abrupt, while others, such as between Mandarin and Xiang or between Min and Hakka, are much less clearly defined.[25] Several east-west isoglosses run along the Huai and Yangtze Rivers.[67] A north-south barrier is formed by the Tianmu and Wuyi Mountains.[68]

Intelligibility testing

Most assessments of mutual intelligibility of varieties of Chinese in the literature are impressionistic.[69] Functional intelligibility testing is time-consuming in any language family, and usually not done when more than 10 varieties are to be compared.[70] However, one 2009 study aimed to measure intelligibility between 15 Chinese provinces. In each province, 15 university students were recruited as speakers and 15 older rural inhabitants recruited as listeners. The listeners were then tested on their comprehension of isolated words and of particular words in the context of sentences spoken by speakers from all 15 of the provinces surveyed.[71] The results demonstrated significant levels of unintelligibility between areas, even within the Mandarin group. In a few cases, listeners understood fewer than 70% of words spoken by speakers from the same province, indicating significant differences between urban and rural varieties. As expected from the wide use of Standard Chinese, speakers from Beijing were understood more than speakers from elsewhere.[72] The scores supported a primary division between northern groups (Mandarin and Jin) and all others, with Min as an identifiable branch.[73]

Terminology

Local varieties from different areas of China are often mutually unintelligible, differing at least as much as different Romance languages and perhaps even as much as Indo-European languages as a whole.[74][75][76] These varieties form the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family (with Bai sometimes being included in this grouping).[77] Because speakers share a standard written form, and have a common cultural heritage with long periods of political unity, the varieties are popularly perceived among native speakers as variants of a single Chinese language,[78] and this is also the official position.[79] Conventional English-language usage in Chinese linguistics is to use dialect for the speech of a particular place (regardless of status) while regional groupings like Mandarin and Wu are called dialect groups.[24] Other linguists choose to refer to the major groups as languages.[75] However, each of these groups contains mutually unintelligible varieties.[24] ISO 639-3 and the Ethnologue assign language codes to each of the top-level groups listed above except Min and Pinghua, whose subdivisions are assigned five and two codes respectively.[80]

The Chinese term fāngyán 方言, composed of characters meaning 'place' and 'speech', was the title of the first work of Chinese dialectology in the Han dynasty, and has had a range of meanings in the millennia since.[81] It is used for any regional subdivision of Chinese, from the speech of a village to major branches such as Mandarin and Wu.[82] Linguists writing in Chinese often qualify the term to distinguish different levels of classification.[83] All these terms have customarily been translated into English as dialect, a practice that has been criticized as confusing.[84] The neologisms regionalect and topolect have been proposed as alternative renderings of fangyan.[84][c]

Phonology

The usual unit of analysis is the syllable, traditionally analysed as consisting of an initial consonant, a final and a tone.[86] In general, southern varieties have fewer initial consonants than northern and central varieties, but more often preserve the Middle Chinese final consonants.[87] Some varieties, such as Cantonese, Hokkien and Shanghainese, include syllabic nasals as independent syllables.[88]

Initials

In the 42 varieties surveyed in the Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects, the number of initials (including a zero initial) ranges from 15 in some southern dialects to a high of 35 in Chongming dialect, spoken in Chongming Island, Shanghai.[89]

| Fuzhou (Min) | Suzhou (Wu) | Beijing (Mandarin) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops and affricates |

voiceless aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | kʰ | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | tɕʰ | kʰ | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | tɕʰ | tʂʰ | kʰ | ||||||

| voiceless unaspirated | p | t | ts | k | p | t | ts | tɕ | k | p | t | ts | tɕ | tʂ | k | |||||||

| voiced | b | d | dʑ | ɡ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | voiceless | s | x | f | s | ɕ | h | f | s | ɕ | ʂ | x | ||||||||||

| voiced | v | z | ʑ | ɦ | ɻ/ʐ | |||||||||||||||||

| Sonorants | l | ∅ | l | ∅ | l | ∅ | ||||||||||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | m | n | |||||||||||||

The initial system of the Fuzhou dialect of northern Fujian is a minimal example.[93] With the exception of /ŋ/, which is often merged with the zero initial, the initials of this dialect are present in all Chinese varieties, although several varieties do not distinguish /n/ from /l/. However, most varieties have additional initials, due to a combination of innovations and retention of distinctions from Middle Chinese:

- Most non-Min varieties have a labiodental fricative /f/, which developed from Middle Chinese bilabial stops in certain environments.[94]

- The voiced initials of Middle Chinese are retained in Wu dialects such as Suzhou and Shanghai, as well as Old Xiang dialects and a few Gan dialects, but have merged with voiceless initials elsewhere.[95][96] Southern Min varieties have an unrelated series of voiced initials resulting from devoicing of nasal initials in syllables without nasal finals.[97]

- The Middle Chinese retroflex initials are retained in many Mandarin dialects, including Beijing but not southwestern and southeastern Mandarin varieties.[98]

- In many northern and central varieties there is palatalization of dental affricates, velars (as in Suzhou), or both. In many places, including Beijing, palatalized dental affricates and palatalized velars have merged to form a new palatal series.[99]

- Maps of the distributions of various initial consonants in the core Chinese-speaking area

-

voiced obstruent initials[100]

-

retroflex initials[101]

-

velar nasal initial (ŋ)[102]

-

retained m- where Beijing has w-[103]

-

retained n- where Beijing has r-[104]

Finals

Chinese finals may be analysed as an optional medial glide, a main vowel and an optional coda.[106]

Conservative vowel systems, such as those of Gan dialects, have high vowels /i/, /u/ and /y/, which also function as medials, mid vowels /e/ and /o/, and a low /a/-like vowel.[107] In other dialects, including Mandarin dialects, /o/ has merged with /a/, leaving a single mid vowel with a wide range of allophones.[108] Many dialects, particularly in northern and central China, have apical or retroflex vowels, which are syllabic fricatives derived from high vowels following sibilant initials.[109] In many Wu dialects, vowels and final glides have monophthongized, producing a rich inventory of vowels in open syllables.[110] Reduction of medials is common in Yue dialects.[111]

The Middle Chinese codas, consisting of glides /j/ and ?pojem=, nasals /m/, /n/ and /ŋ/, and stops /p/, /t/ and /k/, are best preserved in southern dialects, particularly Yue dialects such as Cantonese.[41] In some Min dialects, nasals and stops following open vowels have shifted to nasalization and glottal stops respectively.[112] In Jin, Lower Yangtze Mandarin and Wu dialects, the stops have merged as a final glottal stop, while in most northern varieties they have disappeared.[113] In Mandarin dialects final /m/ has merged with /n/, while some central dialects have a single nasal coda, in some cases realized as a nasalization of the vowel.[114]

Tones

All varieties of Chinese, like neighbouring languages in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, have phonemic tones. Each syllable may be pronounced with between three and seven distinct pitch contours, denoting different morphemes. For example, the Beijing dialect distinguishes mā (妈/媽 'mother'), má (麻 'hemp'), mǎ (马/馬 'horse) and mà (骂/罵 'to scold'). The number of tonal contrasts varies between dialects, with Northern dialects tending to have fewer distinctions than Southern ones.[116] Many dialects have tone sandhi, in which the pitch contour of a syllable is affected by the tones of adjacent syllables in a compound word or phrase.[117] This process is so extensive in Shanghainese that the tone system is reduced to a pitch accent system much like modern Japanese.

The tonal categories of modern varieties can be related by considering their derivation from the four tones of Middle Chinese, though cognate tonal categories in different dialects are often realized as quite different pitch contours.[118] Middle Chinese had a three-way tonal contrast in syllables with vocalic or nasal endings. The traditional names of the tonal categories are 'level'/'even' (平 píng), 'rising' (上 shǎng) and 'departing'/'going' (去 qù). Syllables ending in a stop consonant /p/, /t/ or /k/ (checked syllables) had no tonal contrasts but were traditionally treated as a fourth tone category, 'entering' (入 rù), corresponding to syllables ending in nasals /m/, /n/, or /ŋ/.[119]

The tones of Middle Chinese, as well as similar systems in neighbouring languages, experienced a tone split conditioned by syllabic onsets. Syllables with voiced initials tended to be pronounced with a lower pitch, and by the late Tang dynasty, each of the tones had split into two registers conditioned by the initials, known as "upper" (阴/陰 yīn) and "lower" (阳/陽 yáng).[120] When voicing was lost in all dialects except in the Wu and Old Xiang groups, this distinction became phonemic, yielding eight tonal categories, with a six-way contrast in unchecked syllables and a two-way contrast in checked syllables.[121] Cantonese maintains these eight tonal categories and has developed an additional distinction in checked syllables.[122] (The latter distinction has disappeared again in many varieties.)

However, most Chinese varieties have reduced the number of tonal distinctions.[118] For example, in Mandarin, the tones resulting from the split of Middle Chinese rising and departing tones merged, leaving four tones. Furthermore, final stop consonants disappeared in most Mandarin dialects, and such syllables were distributed amongst the four remaining tones in a manner that is only partially predictable.[123]

| Middle Chinese tone and initial | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| level | rising | departing | entering | |||||||||||

| vl. | n. | vd. | vl. | n. | vd. | vl. | n. | vd. | vl. | n. | vd. | |||

| Jin[124] | Taiyuan | 1 ˩ | 3 ˥˧ | 5 ˥ | 7 ˨˩ | 8 ˥˦ | ||||||||

| Mandarin[124] | Xi'an | 1 ˧˩ | 2 ˨˦ | 3 ˦˨ | 5 ˥ | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Beijing | 1 ˥ | 2 ˧˥ | 3 ˨˩˦ | 5 ˥˩ | 1,2,3,5 | 5 | 2 | |||||||

| Chengdu | 1 ˦ | 2 ˧˩ | 3 ˥˧ | 5 ˩˧ | 2 | |||||||||

| Yangzhou | 1 ˨˩ | 2 ˧˥ | 3 ˧˩ | 5 ˥ | 7 ˦

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Varieties_of_Chinese Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||||||||