A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Most Serene Republic of Venice | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 697–1797 | |||||||||||||||

Coat of arms

(16–18th cent.) | |||||||||||||||

| Motto: Viva San Marco | |||||||||||||||

| Greater coat of arms (1706) | |||||||||||||||

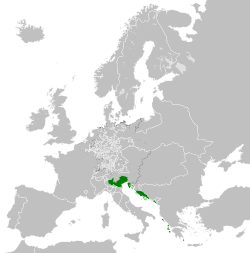

The Republic of Venice in 1789, on the eve of the French Revolution | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||||||

| Minority languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (state) | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Venetian | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary mixed parliamentary classical republic under a mercantile oligarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Doge | |||||||||||||||

• 697–717 (first) | Paolo Lucio Anafestoa | ||||||||||||||

• 1789–1797 (last) | Ludovico Manin | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Great Council (since 1172) | ||||||||||||||

• Upper chamber | Senate | ||||||||||||||

• Lower chamber | Council of Ten (since 1310) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | |||||||||||||||

• Establishment under first dogea as province of the Byzantine Empire | 697 | ||||||||||||||

• Pactum Lotharii (recognition of de facto independence, "province" dropped from name) | 840 | ||||||||||||||

• Golden Bull of Alexios I | 1082 | ||||||||||||||

| 1177 | |||||||||||||||

| 1204 | |||||||||||||||

| 1412 | |||||||||||||||

| 1571 | |||||||||||||||

| 1718 | |||||||||||||||

| 1797 | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Venetian ducat Venetian lira | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

a. ^ Paolo Lucio Anafesto is traditionally the first Doge of Venice, but John Julius Norwich suggests that this may be a mistake for Paul, Exarch of Ravenna, and that the traditional second doge Marcello Tegalliano may have been the similarly named magister militum to Paul. Their existence as doges is uncorroborated by any source before the 11th century, but as Norwich suggests, is probably not entirely legendary. Traditionally, the establishment of the Republic is, thus, dated to 697 AD, not to the installation of the first contemporaneously recorded doge, Orso Ipato, in 726. | |||||||||||||||

The Republic of Venice,[a] traditionally known as La Serenissima,[b] was a sovereign state and maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 by Paolo Lucio Anafesto, over the course of its 1,100 years of history it established itself as one of the major European commercial and naval powers. Initially extended in the Dogado area (a territory currently comparable to the Metropolitan City of Venice), during its history it annexed a large part of Northeast Italy, Istria, Dalmatia, the coasts of present-day Montenegro and Albania as well as numerous islands in the Adriatic and eastern Ionian seas. At the height of its expansion, between the 13th and 16th centuries, it also governed the Peloponnese, Crete and Cyprus, most of the Greek islands, as well as several cities and ports in the eastern Mediterranean.

The islands of the Venetian Lagoon in the 7th century, after having experienced a period of substantial increase in population, were organized into Maritime Venice, a Byzantine duchy dependent on the Exarchate of Ravenna. With the fall of the Exarchate and the weakening of Byzantine power, the Duchy of Venice arose, led by a doge and established on the island of Rialto; it prospered from maritime trade with the Byzantine Empire and other eastern states. In order to safeguard the trade routes, between the 9th and 11th centuries the Duchy waged several wars, which ensured its complete dominion over the Adriatic. Owing to participation in the Crusades, penetration into eastern markets became increasingly stronger and, between the 12th and 13th centuries, Venice managed to extend its power into numerous eastern emporiums and commercial ports. The supremacy over the Mediterranean Sea led the Republic to the clash with Genoa, which lasted until the 14th century, when, after having risked complete collapse during the War of Chioggia (with the Genoese army and fleet in the lagoon for a long period), Venice quickly managed to recover from the territorial losses suffered with the Treaty of Turin of 1381 and begin expansion on the mainland.

Venetian expansion, however, led to the coalition of the Habsburg monarchy, Spain and France in the League of Cambrai, which in 1509 defeated the Republic of Venice in the Battle of Agnadello. While maintaining most of its mainland possessions, Venice was defeated and the attempt to expand the eastern dominions caused a long series of wars against the Ottoman Empire, which ended only in the 18th century with the Treaty of Passarowitz of 1718 and which caused the loss of all possessions in the Aegean. Although still a thriving cultural centre, the Republic of Venice was occupied by Napoleon's French troops and its territories were divided with the Habsburg monarchy following the ratification of the Treaty of Campo Formio.

Throughout its history, the Republic of Venice was characterized by its political order. Inherited from the previous Byzantine administrative structures, its head of state was the doge, a position which became elective from the end of the 9th century. In addition to the doge, the administration of the Republic was directed by various assemblies: the Great Council, with legislative functions, which was supported by the Minor Council, the council of Forty and the Council of Ten responsible for judicial matters and the Senate.

Etymology

During its long history, the Republic of Venice took on various names, all closely linked to the titles attributed to the doge. During the 8th century, when Venice still depended on the Byzantine Empire, the doge was called in Latin Dux Venetiarum Provinciae ('Doge of the Province of Venice'),[3] and then, starting from 840, Dux Veneticorum ('Doge of the Venetians'), following the signing of the Pactum Lotharii. This commercial agreement, stipulated between the Duchy of Venice (Ducatum Venetiae) and the Carolingian Empire, de facto ratified the independence of Venice from the Byzantine Empire.[4][5][6]

In the following century, references to Venice as a Byzantine dominion disappeared, and in a document from 976 there is a mention of the most glorious Domino Venetiarum ('Lord of Venice'), where the 'most glorious' appellative had already been used for the first time in the Pactum Lotharii and where the appellative "lord" refers to the fact that the doge was still considered like a king, even if elected by the popular assembly.[7][8] Gaining independence, Venice also began to expand on the coasts of the Adriatic Sea, and so starting from 1109, following the conquest of Dalmatia and the Croatian coast, the doge formally received the title of Venetiae Dalmatiae atque Chroatiae Dux ('Doge of Venice, Dalmatia and Croatia'),[9][10] a name that continued to be used until the 18th century.[11] Starting from the 15th century, the documents written in Latin were joined by those in the Venetian language, and in parallel with the events in Italy, the Duchy of Venice also changed its name, becoming the Lordship of Venice, which as written in the peace treaty of 1453 with Sultan Mehmed II was fully named the lIlustrissima et Excellentissima deta Signoria de Venexia ('The Most Illustrious and Excellent Signoria of Venice').[12]

During the 17th century, monarchical absolutism asserted itself in many countries of continental Europe, radically changing the European political landscape. This change made it possible to more markedly determine the differences between monarchies and republics: while the former had economies governed by strict laws and dominated by agriculture, the latter lived off of commercial affairs and free markets. Moreover, the monarchies, in addition to being led by a single ruling family, were more prone to war and religious uniformity. This increasingly noticeable difference between monarchy and republic began to be specified also in official documents, and it was hence that names such as the Republic of Genoa or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces were born. The Lordship of Venice also adapted to this new terminology, becoming the Most Serene Republic of Venice (Italian: Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia; Venetian: Serenìsima Repùblega de Venexia), a name by which it is best known today.[13][14][15][16] Similarly, the doge was also given the nickname of serenissimo[11] or more simply that of His Serenity.[17] From the 17th century the Republic of Venice took on other more or less official names such as the Venetian State or the Venetian Republic. The republic is often referred to as La Serenissima, in reference to its title as one of the "Most Serene Republics".[18]

History

9th-10th century: The ducal age

The Duchy of Venice was born in the 9th century from the Byzantine territories of Maritime Venice. According to tradition, the first doge was elected in 697, but this figure is of dubious historicity and comparable to that of the exarch Paul, who, similarly to the doge, was assassinated in 727 following a revolt. Father Pietro Antonio of Venetia, in his history of the lagoon city published in 1688, writes: "The precise time in which that family arrived in the Adria is not found, but rather, what already an inhabitant of the islands, by the princes, who welcomed citizens, and supported with the advantage of significant riches, in the year 697 she contributed to the nomination of the first Prince Marco Contarini, one of the 22 Tribunes of the Islands, who made the election". In 726, Emperor Leo III attempted to extend iconoclasm to the Exarchate of Ravenna, causing numerous revolts throughout the territory. In reaction to the reform, the local populations appointed several dux to replace the Byzantine governors and in particular Venetia appointed Orso as its doge, who governed the lagoon for a decade. Following his death, the Byzantines entrusted the government of the province to the regime of the magistri militum, which lasted until 742 when the emperor granted the people the appointment of a dux. The Venetians elected by acclamation Theodato, son of Orso, who decided to move the capital of the duchy from Heraclia to Metamauco.[19]

The Lombard conquest of Ravenna in 751 and the subsequent conquest of the Lombard kingdom by Charlemagne's Franks in 774, with the creation of the Carolingian Empire in 800, considerably changed the geopolitical context of the lagoon, leading the Venetians to divide into two factions : a pro-Frankish party led by the city of Equilium and a pro-Byzantine party with a stronghold in Heraclia. After a long series of skirmishes in 805, Doge Obelerio decided to attack both cities simultaneously, deporting their population to the capital. Having taken control of the situation, the doge placed Venezia under Frankish protection, but a Byzantine naval blockade convinced him to renew his loyalty to the Eastern Emperor. With the intention of conquering Venezia in 810, the Frankish army commanded by Pepin invaded the lagoon, forcing the local population to retreat to Rivoalto, thus starting a siege which ended with the arrival of the Byzantine fleet and the retreat of the Franks. Following the failed Frankish conquest, Doge Obelerio was replaced by the pro-Byzantine nobleman Agnello Participazio who definitively moved the capital to Rivoalto in 812, thus decreeing the birth of the city of Venice.[20]

With his election, Agnello Partecipazio attempted to make the ducal office hereditary by associating an heir, the co-dux, with the throne. The system brought Agnello's two sons, Giustiniano and Giovanni, to the ducal position, who was deposed in 836 due to his inadequacy to counter the Narentine pirates in Dalmatia.[21] Following the deposition of Giovanni Partecipazio, Pietro Tradonico was elected who, with the promulgation of the Pactum Lotharii, a commercial treaty between Venice and the Carolingian Empire, began the long process of detachment of the province from the Byzantine Empire.[22] After Tradonico was killed following a conspiracy in 864, Orso I Participazio was elected and resumed the fight against piracy, managing to protect the Dogado from attacks by the Saracens and the Patriarchate of Aquileia. Orso managed to assign the dukedom to his eldest son Giovanni II Participazio who, after conquering Comacchio, a rival city of Venice in the salt trade, decided to abdicate in favor of his brother, at the time patriarch of Grado, who refused. Since there was no heir in 887 the people gathered in the Concio and elected Pietro I Candiano by acclamation.[23]

The Concio managed to elect six doges up to Pietro III Candiano who in 958 assigned the position of co-dux to his son Pietro who became doge the following year. Due to his land holdings, Pietro IV Candiano had a political vision close to that of the Holy Roman Empire and consequently attempted to establish feudalism in Venice as well, causing a revolt in 976 which led to the burning of the capital and the killing of the doge.[24] These events led the Venetian patriciate to gain a growing influence on the doge's policies and the conflicts that arose following the doge's assassination were resolved only in 991 with the election of Pietro II Orseolo.[25]

11th-12th century: Relations with the Byzantine Empire

Pietro II Orseolo gave a notable boost to Venetian commercial expansion by stipulating new commercial privileges with the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire. In addition to diplomacy, the doge resumed the war against the Narentan pirates that began in the 9th century and in the year 1000 he managed to subjugate the coastal cities of Istria and Dalmatia.[26] The Great Schism of 1054 and the outbreak of the investiture struggle in 1073 marginally involved Venetian politics which instead focused its attention on the arrival of the Normans in southern Italy. The Norman occupation of Durrës and Corfu in 1081 pushed the Byzantine Empire to request the aid of the Venetian fleet which, with the promise of obtaining extensive commercial privileges and reimbursement of military expenses, decided to take part in the Byzantine-Norman wars.[27] The following year, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos granted Venice the chrysobol, a commercial privilege that allowed Venetian merchants substantial tax exemptions in numerous Byzantine ports and the establishment of a Venetian neighbourhood in Durrës and Constantinople. The war ended in 1085 when, following the death of the leader Robert Guiscard, the Norman army abandoned its positions to return to Puglia.[28]

Having taken office in 1118, Emperor John II Komnenos decided not to renew the chrysobol of 1082, arousing the reaction of Venice which declared war on the Byzantine Empire in 1122. The war ended in 1126 with the victory of Venice which forced the emperor to stipulate a new agreement characterized by even better conditions than the previous ones, thus making the Byzantine Empire totally dependent on Venetian trade and protection.[29] With the intention of weakening the growing Venetian power, the emperor provided substantial commercial support to the maritime republics of Ancona, Genoa and Pisa, making coexistence with Venice, which was now hegemonic on the Adriatic Sea, increasingly difficult, so much so that it was renamed the "Gulf of Venice". In 1171, following the emperor's decision to expel the Venetian merchants from Constantinople, a new war broke out which was resolved with the restoration of the status quo.[30] At the end of the 12th century, the commercial traffic of Venetian merchants extended throughout the East and they could count on immense and solid capital.[31]

As in the rest of Italy, starting from the 12th century, Venice also underwent the transformations that led to the age of the municipalities. In that century, the doge's power began to decline: initially supported only by a few judges, in 1130 it was decided to place the Consilium Sapientium, which would later become the Great Council of Venice, alongside his power. In the same period, in addition to the expulsion of the clergy from public life, new assemblies such as the Council of Forty and the Minor Council were established and in his inauguration speech the Doge was forced to declare loyalty to the Republic with the promissione ducale;[32] thus the Commune of Venice, the set of all the assemblies aimed at regulating the power of the doge, began to take shape.[33]

13th-14th century: The Crusades and the rivalry with Genoa

In the 12th century, Venice decided not to participate in the Crusades due to its commercial interests in the East and instead concentrated on maintaining its possessions in Dalmatia which were repeatedly besieged by the Hungarians. The situation changed in 1202 when the Doge Enrico Dandolo decided to exploit the expedition of the Fourth Crusade to conclude the Zara War and the following year, after twenty years of conflict, Venice conquered the city and won the war, regaining control of Dalmatia.[34] The Venetian crusader fleet, however, did not stop in Dalmatia, but continued towards Constantinople to besiege it in 1204, thus putting an end to the Byzantine Empire and formally making Venice an independent state, severing the last ties with the former Byzantine ruler.[35] The empire was dismembered in the Crusader states and from the division Venice obtained numerous ports in the Morea and several islands in the Aegean Sea including Crete and Euboea, thus giving life to the Stato da Màr. In addition to the territorial conquests, the doge was awarded the title of Lord of a quarter and a half of the Eastern Roman Empire, thus obtaining the faculty of appointing the Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople and the possibility of sending a Venetian representative to the government of the Eastern Latin Empire.[36] With the end of the Fourth Crusade, Venice concentrated its efforts on the conquest of Crete, which intensely involved the Venetian army until 1237.[37]

Venice's control over the eastern trade routes became pressing and this caused an increase in conflicts with Genoa which in 1255 exploded into the War of Saint Sabas; on 24 June 1258 the two republics faced each other in the Battle of Acre which ended with an overwhelming Venetian victory. In 1261 the Empire of Nicaea with the help of the Republic of Genoa managed to dissolve the Eastern Latin Empire and re-establish the Byzantine Empire. The war between Genoa and Venice resumed and after a long series of battles the war ended in 1270 with the Peace of Cremona.[38] In 1281 Venice defeated the Republic of Ancona in battle and in 1293 a new war between Genoa, the Byzantine Empire and Venice broke out, won by the Genoese following the Battle of Curzola and ending in 1299.[39]

During the war, various administrative reforms were implemented in Venice, new assemblies were established to replace popular ones such as the Senate and in the Great Council power began to concentrate in the hands of about ten families. In order to avoid the birth of a lordship, the Doge decided to increase the number of members of the Maggior Consiglio while leaving the number of families unchanged and so the Serrata del Maggior Consiglio was implemented in 1297.[40] Following the provision, the power of some of the old houses decreased and in 1310, under the pretext of defeat in the Ferrara War, these families organized themselves in the Tiepolo conspiracy.[41] Once the coup d'état failed and the establishment of a lordship was averted, Doge Pietro Gradenigo established the Council of Ten, which was assigned the task of repressing any threat to the security of the state.[42]

In the Venetian hinterland, the war waged by Mastino II della Scala caused serious economic losses to Venetian trade, so in 1336 Venice gave birth to the anti-Scaliger league. The following year the coalition expanded further and Padua returned to the dominion of the Carraresi. In 1338, Venice conquered Treviso, the first nucleus of the Domini di Terraferma, and in 1339 it signed a peace treaty in which the Scaligeri promised not to interfere in Venetian trade and to recognize the sovereignty of Venice over the Trevisan March.[43]

In 1343 Venice took part in the Smyrniote crusades, but its participation was suspended due to the siege of Zadar by the Hungarians. The Genoese expansion to the east, which caused the Black Death, brought the rivalry between the two republics to resurface and in 1350 they faced each other in the War of the Straits. Following the defeat in the Battle of Sapienza, Doge Marino Faliero attempted to establish a city lordship, but the coup d'état was foiled by the Council of Ten which on 17 April 1355 condemned the Doge to death. The ensuing political instability convinced Louis I of Hungary to attack Dalmatia which was conquered in 1358 with the signing of the Treaty of Zadar. The weakness of the Republic pushed Crete and Trieste to revolt, but the rebellions were quelled, thus reaffirming Venetian dominion over the Stato da Màr. The skirmishes between the Venetians and the Genoese resumed and in 1378 the two republics faced each other in the War of Chioggia. Initially the Genoese managed to conquer Chioggia and vast areas of the Venetian Lagoon, but in the end it was the Venetians who prevailed; the war ended definitively on 8 August 1381 with the Treaty of Turin which sanctioned the exit of the Genoese from the competition for dominion over the Mediterranean.[44]

15th century: Territorial expansion

In 1403, the last major battle between the Genoese (now under French rule) and Venice was fought at Modon, and the final victory resulted in maritime hegemony and dominance of the eastern trade routes. The latter would soon be contested, however, by the inexorable rise of the Ottoman Empire. Hostilities began after Prince Mehmed I ended the civil war of the Ottoman Interregnum and established himself as sultan. The conflict escalated until Pietro Loredan won a crushing victory against the Turks off Gallipoli in 1416.

Venice expanded as well along the Dalmatian coast from Istria to Albania, which was acquired from King Ladislaus of Naples during the civil war in Hungary. Ladislaus was about to lose the conflict and had decided to escape to Naples, but before doing so he agreed to sell his now practically forfeit rights on the Dalmatian cities for the reduced sum of 100,000 ducats. Venice exploited the situation and quickly installed nobility to govern the area, for example, Count Filippo Stipanov in Zara. This move by the Venetians was a response to the threatening expansion of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan. Control over the northeast main land routes was also a necessity for the safety of the trades. By 1410, Venice had a navy of 3,300 ships (manned by 36,000 men) and had taken over most of what is now the Veneto, including the cities of Verona (which swore its loyalty in the Devotion of Verona to Venice in 1405) and Padua.[45]

Slaves were plentiful in the Italian city-states as late as the 15th century. The Venetian slave trade was divided in to the Balkan slave trade and the Black Sea slave trade. Between 1414 and 1423, some 10,000 slaves, imported from Caffa (via the Black Sea slave trade), were sold in Venice.[46]

In the early 15th century, the republic began to expand onto the Terraferma. Thus, Vicenza, Belluno, and Feltre were acquired in 1404, and Padua, Verona, and Este in 1405. The situation in Dalmatia had been settled in 1408 by a truce with King Sigismund of Hungary, but the difficulties of Hungary finally granted to the republic the consolidation of its Adriatic dominions. The situation culminated in the Battle of Motta in late August 1412, when an invading army of Hungarians, Germans and Croats, led by Pippo Spano and Voivode Miklós Marczali[47] attacked the Venetian positions at Motta[48] and suffered a heavy defeat. At the expiration of the truce in 1420, Venice immediately invaded the Patriarchate of Aquileia and subjected Traù, Spalato, Durazzo, and other Dalmatian cities. In Lombardy, Venice acquired Brescia in 1426, Bergamo in 1428, and Cremona in 1499.

In 1454, a conspiracy for a rebellion against Venice was dismantled in Candia. The conspiracy was led by Sifis Vlastos as an opposition to the religious reforms for the unification of Churches agreed at the Council of Florence.[49] In 1481, Venice retook nearby Rovigo, which it had held previously from 1395 to 1438.

The Ottoman Empire started sea campaigns as early as 1423, when it waged a seven-year war with the Venetian Republic over maritime control of the Aegean, the Ionian, and the Adriatic Seas. The wars with Venice resumed after the Ottomans captured the Kingdom of Bosnia in 1463, and lasted until a favorable peace treaty was signed in 1479 just after the troublesome siege of Shkodra. In 1480, no longer hampered by the Venetian fleet, the Ottomans besieged Rhodes and briefly captured Otranto.

In February 1489, the island of Cyprus, previously a crusader state (the Kingdom of Cyprus), was added to Venice's holdings. By 1490, the population of Venice had risen to about 180,000 people.[50]

16th century: League of Cambrai, the loss of Cyprus, and Battle of Lepanto

War with the Ottomans resumed from 1499 to 1503. In 1499, Venice allied itself with Louis XII of France against Milan, gaining Cremona. In the same year, the Ottoman sultan moved to attack Lepanto by land and sent a large fleet to support his offensive by sea. Antonio Grimani, more a businessman and diplomat than a sailor, was defeated in the sea battle of Zonchio in 1499. The Turks once again sacked Friuli. Preferring peace to total war both against the Turks and by sea, Venice surrendered the bases of Lepanto, Durazzo, Modon, and Coron.

Venice's attention was diverted from its usual maritime position by the delicate situation in Romagna, then one of the richest lands in Italy, which was nominally part of the Papal States, but effectively divided into a series of small lordships which were difficult for Rome's troops to control. Eager to take some of Venice's lands, all neighbouring powers joined in the League of Cambrai in 1508, under the leadership of Pope Julius II. The pope wanted Romagna; Emperor Maximilian I: Friuli and Veneto; Spain: the Apulian ports; the king of France: Cremona; the king of Hungary: Dalmatia, and each one some of another's part. The offensive against the huge army enlisted by Venice was launched from France.

On 14 May 1509, Venice was crushingly defeated at the battle of Agnadello, in the Ghiara d'Adda, marking one of the most delicate points in Venetian history. French and imperial troops were occupying Veneto, but Venice managed to extricate itself through diplomatic efforts. The Apulian ports were ceded in order to come to terms with Spain, and Julius II soon recognized the danger brought by the eventual destruction of Venice (then the only Italian power able to face kingdoms like France or empires like the Ottomans).

The citizens of the mainland rose to the cry of "Marco, Marco", and Andrea Gritti recaptured Padua in July 1509, successfully defending it against the besieging imperial troops. Spain and the pope broke off their alliance with France, and Venice regained Brescia and Verona from France, also. After seven years of ruinous war, the Serenissima regained its mainland dominions west to the Adda River. Although the defeat had turned into a victory, the events of 1509 marked the end of the Venetian expansion.

In 1489, the first year of Venetian control of Cyprus, Turks attacked the Karpasia Peninsula, pillaging and taking captives to be sold into slavery. In 1539, the Turkish fleet attacked and destroyed Limassol. Fearing the ever-expanding Ottoman Empire, the Venetians had fortified Famagusta, Nicosia, and Kyrenia, but most other cities were easy prey. By 1563, the population of Venice had dropped to about 168,000 people.[50]

In the summer of 1570, the Turks struck again but this time with a full-scale invasion rather than a raid. About 60,000 troops, including cavalry and artillery, under the command of Mustafa Pasha landed unopposed near Limassol on 2 July 1570 and laid siege to Nicosia. In an orgy of victory on the day that the city fell – 9 September 1570 – 20,000 Nicosians were put to death, and every church, public building, and palace was looted.[51] Word of the massacre spread, and a few days later, Mustafa took Kyrenia without having to fire a shot. Famagusta, however, resisted and put up a defense that lasted from September 1570 until August 1571.

The fall of Famagusta marked the beginning of the Ottoman period in Cyprus. Two months later, the naval forces of the Holy League, composed mainly of Venetian, Spanish, and papal ships under the command of Don John of Austria, defeated the Turkish fleet at the battle of Lepanto.[52] Despite victory at sea over the Turks, Cyprus remained under Ottoman rule for the next three centuries. By 1575, the population of Venice was about 175,000 people, but partly as a result of the plague of 1575–76 the population dropped to 124,000 people by 1581.[50]

17th century

According to economic historian Jan De Vries, Venice's economic power in the Mediterranean had declined significantly by the start of the 17th century. De Vries attributes this decline to the loss of the spice trade, a declining uncompetitive textile industry, competition in book publishing from a rejuvenated Catholic Church, the adverse impact of the Thirty Years' War on Venice's key trade partners, and the increasing cost of cotton and silk imports to Venice.[53]

In 1606, a conflict between Venice and the Holy See began with the arrest of two clerics accused of petty crimes and with a law restricting the Church's right to enjoy and acquire landed property. Pope Paul V held that these provisions were contrary to canon law, and demanded that they be repealed. When this was refused, he placed Venice under an interdict which forbade clergymen from exercising almost all priestly duties. The republic paid no attention to the interdict or the act of excommunication and ordered its priests to carry out their ministry. It was supported in its decisions by the Servite friar Paolo Sarpi, a sharp polemical writer who was nominated to be the Signoria's adviser on theology and canon law in 1606. The interdict was lifted after a year, when France intervened and proposed a formula of compromise. Venice was satisfied with reaffirming the principle that no citizen was superior to the normal processes of law.[54]

Rivalry with Habsburg Spain and the Holy Roman Empire led to Venice's last significant wars in Italy and the northern Adriatic. Between 1615 and 1618 Venice fought Archduke Ferdinand of Austria in the Uskok war in the northern Adriatic and on the Republic's eastern border, while in Lombardy to the west, Venetian troops skirmished with the forces of Don Pedro de Toledo Osorio, Spanish governor of Milan, around Crema in 1617 and in the countryside of Romano di Lombardia in 1618. A fragile peace did not last, and in 1629 the Most Serene Republic returned to war with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire in the War of the Mantuan succession. During the brief war a Venetian army led by provveditore Zaccaria Sagredo and reinforced by French allies was disastrously routed by Imperial forces at the battle of Villabuona, and Venice's closest ally Mantua was sacked. Reversals elsewhere for the Holy Roman Empire and Spain ensured the republic suffered no territorial loss, and the duchy of Mantua was restored to Charles II Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers, who was the candidate backed by Venice and France.

The latter half of the 17th century also had prolonged wars with the Ottoman Empire; in the Cretan War (1645–1669), after a heroic siege that lasted 21 years, Venice lost its major overseas possession – the island of Crete (although it kept the control of the bases of Spinalonga and Suda) – while it made some advances in Dalmatia. In 1684, however, taking advantage of the Ottoman involvement against Austria in the Great Turkish War, the republic initiated the Morean War, which lasted until 1699 and in which it was able to conquer the Morea peninsula in southern Greece.

18th century: Decline

These gains did not last, however; in December 1714, the Turks began the last Turkish–Venetian War, when the Morea was "without any of those supplies which are so desirable even in countries where aid is near at hand which are not liable to attack from the sea".[55]

The Turks took the islands of Tinos and Aegina, crossed the isthmus, and took Corinth. Daniele Dolfin, commander of the Venetian fleet, thought it better to save the fleet than risk it for the Morea. When he eventually arrived on the scene, Nauplia, Modon, Corone, and Malvasia had fallen. Levkas in the Ionian islands, and the bases of Spinalonga and Suda on Crete, which still remained in Venetian hands, were abandoned. The Turks finally landed on Corfu, but its defenders managed to throw them back.

In the meantime, the Turks had suffered a grave defeat by the Austrians in the Battle of Petrovaradin on 5 August 1716. Venetian naval efforts in the Aegean Sea and the Dardanelles in 1717 and 1718, however, met with little success. With the Treaty of Passarowitz (21 July 1718), Austria made large territorial gains, but Venice lost the Morea, for which its small gains in Albania and Dalmatia were little compensation. This was the last war with the Ottoman Empire. By the year 1792, the once-great Venetian merchant fleet had declined to a mere 309 merchantmen.[56] Although Venice declined as a seaborne empire, it remained in possession of its continental domain north of the Po Valley, extending west almost to Milan. Many of its cities benefited greatly from the Pax Venetiae (Venetian peace) throughout the 18th century.

Angelo Emo was named the last Captain General of the Sea (Capitano Generale da Mar) of the Republic in 1784.

Fall

By 1796, the Republic of Venice could no longer defend itself since its war fleet numbered only four galleys and seven galiots.[57] In spring 1796, Piedmont (the Duchy of Savoy) fell to the invading French, and the Austrians were beaten from Montenotte to Lodi. The army under Napoleon crossed the frontiers of neutral Venice in pursuit of the enemy. By the end of the year, the French troops were occupying the Venetian state up to the Adige River. Vicenza, Cadore and Friuli were held by the Austrians. With the campaigns of the next year, Napoleon aimed for the Austrian possessions across the Alps. In the preliminaries to the Peace of Leoben, the terms of which remained secret, the Austrians were to take the Venetian possessions in the Balkans as the price of peace (18 April 1797) while France acquired the Lombard part of the state.

After Napoleon's ultimatum, Ludovico Manin surrendered unconditionally on 12 May and abdicated, while the Major Council declared the end of the republic. According to Bonaparte's orders, the public powers passed to a provisional municipality under the French military governor. On 17 October, France and Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, agreeing to share all the territory of the republic, with a new border just west of the Adige. Italian democrats, especially young poet Ugo Foscolo, viewed the treaty as a betrayal. The metropolitan part of the disbanded republic became an Austrian territory, under the name of Venetian Province (Provincia Veneta in Italian, Provinz Venedig in German).

Legacy

Though the economic vitality of the Venetian Republic had started to decline since the 16th century with the movement of international trade towards the Atlantic, its political regime still appeared in the 18th century as a model for the philosophers of the Enlightenment.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was hired in July 1743 as secretary by Comte de Montaigu, who had been named ambassador of the French in Venice. This short experience, nevertheless, awakened the interest of Rousseau to the policy, which led him to design a large book of political philosophy.[58] After the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1755), he published The Social Contract (1762).

Politics

Following the Lombard occupation and the progressive migration of the Roman populations, new coastal settlements were born in which the local assemblies, the comitia, elected a Tribune to govern the local administration, perpetuating the Roman custom started in the last years of the Western Roman Empire. Between the end of the 7th century and the beginning of the 8th, a new political reform affected Venetia: like the other Byzantine provinces of Italy it was transformed into a duchy, at the head of which was the doge. Following the brief regime of the magistri militum, in 742 ducal electivity was transferred from the Empire to local assemblies, thus sanctioning the beginning of the ducal monarchy which lasted, with ups and downs, until the 11th century.[59]

If the first stable form of involvement of the patriciate in the management of power occurred with the institution of the curia ducis, starting from 1141 with the beginning of the municipal age, an unstoppable process of limitation and removal of ducal power from part of the nascent mercantile aristocracy gathered in the Great Council, the largest assembly of the Veneciarum municipality. In the 13th century the popular assembly of the concio was progressively stripped of all its powers and, similarly to the Italian city lordships, in Venice too power began to concentrate in the hands of a small number of families.[60] To avoid the birth of a lordship and dilute the power of the old houses, the Lockout of the Great Council took place in 1297, a measure that increased the number of members of the Great Council leaving the number of families unchanged and therefore precluding the entry of the new nobility.[40]

Between the 13th and 14th centuries the power of the doge became purely formal and that of the popular assemblies null and void, even if the tannery was formally abolished only in 1423; this decreed the birth of an oligarchic and aristocratic republic which continued to exist until the fall of the Republic.[61] The organization of the state was entrusted to many nobles divided into numerous assemblies which generally remained in office for less than a year and met in Venice in the Doge's Palace, the political center of the Republic.

Government system

Doge

The Doge (from the Latin dux, or commander) was the head of state of the Republic of Venice, the position lasted for life and his name appeared on coins, ducal bulls, judicial sentences and letters sent to foreign governments. His greatest power was to promulgate laws; he also commanded the army during periods of war and had the Sopragastaldo execute all judicial sentences in his name.[62] The election of the Doge was decreed by an assembly of forty-one electors chosen after a long series of elections and lots, in order to avoid fraud, and once elected the Doge had the obligation to pronounce the promissione ducale, an oath in which was promised loyalty to the Republic and the limitations to its powers were recognized.[63][64]

The Signoria was the most dignified assembly of the Venetian governmental system and was composed of the Doge, the Minor Council and the three leaders of the Quarantia Criminale. The Signoria had the fundamental task of presiding over the major assemblies of the state: the College of the Wise, the Great Council, the Senate and the Council of Ten. The members of the Signoria also had the power to propose and vote on laws in the presided over assemblies and to convene the Great Council at any time. The Minor Council was elected by the Major Council and was made up of six councilors elected three at a time every eight months; since they remained in office for one year, the three outgoing councilors played the role of Inferior Councilors for four months and presided over the Quarantia Criminale representing the Signoria. Within the Minor Council one of the Three State Inquisitors was elected and following the death of the Doge it elected a Deputy Doge and presided over the Republic with the rest of the Signoria.[65][66]

Over the centuries, 120 doges followed one another in Venice. Among the most illustrious names are:

- Paolo Lucio Anafesto, the first Doge of Venice.

- Pietro II Orseolo, who established Venetian dominion over the Adriatic and conquered Dalmatia.

- Enrico Dandolo, who led the Republic of Venice to domination over the Byzantine Empire, giving rise to Venice's maritime empire.

- Marino Faliero, who was beheaded for attempting to found a Lordship.

- Francesco Foscari, who expanded the dominions of the Republic into the mainland.

- Leonardo Loredan, who led Venice in resistance against the League of Cambrai, the coalition of the most important European states against Venice.

- Francesco Morosini, who led Venice in the recovery of Morea (the Peloponnese), the last great redemption of the Republic against the Turks.

- Ludovico Manin, the last Doge of Venice.

College of the Sages

The College of the Sages was composed of three subcommissions called "hands": the Sages of the Council, the Sages of the Mainland and the Sages of the Orders, it constituted the summit of the executive power, was elected by the Senate and when it was presided over by the Signoria it took the name of Full College. There were six Sages of the Council and they established the agenda of the work of the Senate while the Sages of the Orders, initially responsible for the management of the mude and the navy, progressively lost importance. The Sages of the Mainland were five, one was the Sage of the Ceremonials, one the Sage who dealt with the dispatch of the laws, while the other three were proper ministers:

- The Sage of the Finances, analogous to the finance minister, was superior and close collaborator of the camerlenghi;[67]

- The Sage of the Scripture, analogous to the minister of war, was in charge of the economic management of the troops and military justice;[68] Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Venetian_Republic

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk