A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Version control (also known as revision control, source control, and source code management) is the software engineering practice of controlling computer files and versions of files; primarily source code text files, but generally any type of file.

Version control is a component of software configuration management.[1]

A version control system is a software tool that automates version control. Alternatively, version control is embedded as a feature of some systems such as word processors, spreadsheets, collaborative web docs,[2] and content management systems, e.g., Wikipedia's page history.

Version control includes viewing old versions and enables reverting a file to a previous version.

Overview

As teams develop software, it is common for multiple versions of the same software to be deployed in different sites and for the developers to work simultaneously on updates. Bugs or features of the software are often only present in certain versions (because of the fixing of some problems and the introduction of others as the program develops). Therefore, for the purposes of locating and fixing bugs, it is vitally important to be able to retrieve and run different versions of the software to determine in which version(s) the problem occurs. It may also be necessary to develop two versions of the software concurrently: for instance, where one version has bugs fixed, but no new features (branch), while the other version is where new features are worked on (trunk).

At the simplest level, developers could simply retain multiple copies of the different versions of the program, and label them appropriately. This simple approach has been used in many large software projects. While this method can work, it is inefficient as many near-identical copies of the program have to be maintained. This requires a lot of self-discipline on the part of developers and often leads to mistakes. Since the code base is the same, it also requires granting read-write-execute permission to a set of developers, and this adds the pressure of someone managing permissions so that the code base is not compromised, which adds more complexity. Consequently, systems to automate some or all of the revision control process have been developed. This ensures that the majority of management of version control steps is hidden behind the scenes.

Moreover, in software development, legal and business practice, and other environments, it has become increasingly common for a single document or snippet of code to be edited by a team, the members of which may be geographically dispersed and may pursue different and even contrary interests. Sophisticated revision control that tracks and accounts for ownership of changes to documents and code may be extremely helpful or even indispensable in such situations.

Revision control may also track changes to configuration files, such as those typically stored in /etc or /usr/local/etc on Unix systems. This gives system administrators another way to easily track changes made and a way to roll back to earlier versions should the need arise.

Many version control systems identify the version of a file as a number or letter, called the version number, version, revision number, revision, or revision level. For example, the first version of a file might be version 1. When the file is changed the next version is 2. Each version is associated with a timestamp and the person making the change. Revisions can be compared, restored, and, with some types of files, merged.[3]

History

IBM's OS/360 IEBUPDTE software update tool dates back to 1962, arguably a precursor to version control system tools. Two source management and version control packages that were heavily used by IBM 360/370 installations were The Librarian and Panvalet.[4][5]

A full system designed for source code control was started in 1972, Source Code Control System for the same system (OS/360). Source Code Control System's introduction, having been published on December 4, 1975, historically implied it was the first deliberate revision control system.[6] RCS followed just after,[7] with its networked version Concurrent Versions System. The next generation after Concurrent Versions System was dominated by Subversion,[8] followed by the rise of distributed revision control tools such as Git.[9]

Structure

Revision control manages changes to a set of data over time. These changes can be structured in various ways.

Often the data is thought of as a collection of many individual items, such as files or documents, and changes to individual files are tracked. This accords with intuitions about separate files but causes problems when identity changes, such as during renaming, splitting or merging of files. Accordingly, some systems such as Git, instead consider changes to the data as a whole, which is less intuitive for simple changes but simplifies more complex changes.

When data that is under revision control is modified, after being retrieved by checking out, this is not in general immediately reflected in the revision control system (in the repository), but must instead be checked in or committed. A copy outside revision control is known as a "working copy". As a simple example, when editing a computer file, the data stored in memory by the editing program is the working copy, which is committed by saving. Concretely, one may print out a document, edit it by hand, and only later manually input the changes into a computer and save it. For source code control, the working copy is instead a copy of all files in a particular revision, generally stored locally on the developer's computer;[note 1] in this case saving the file only changes the working copy, and checking into the repository is a separate step.

If multiple people are working on a single data set or document, they are implicitly creating branches of the data (in their working copies), and thus issues of merging arise, as discussed below. For simple collaborative document editing, this can be prevented by using file locking or simply avoiding working on the same document that someone else is working on.

Revision control systems are often centralized, with a single authoritative data store, the repository, and check-outs and check-ins done with reference to this central repository. Alternatively, in distributed revision control, no single repository is authoritative, and data can be checked out and checked into any repository. When checking into a different repository, this is interpreted as a merge or patch.

Graph structure

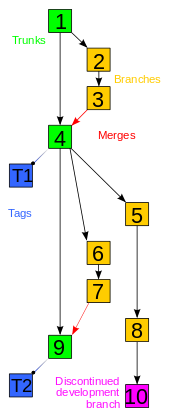

In terms of graph theory, revisions are generally thought of as a line of development (the trunk) with branches off of this, forming a directed tree, visualized as one or more parallel lines of development (the "mainlines" of the branches) branching off a trunk. In reality the structure is more complicated, forming a directed acyclic graph, but for many purposes "tree with merges" is an adequate approximation.

Revisions occur in sequence over time, and thus can be arranged in order, either by revision number or timestamp.[note 2] Revisions are based on past revisions, though it is possible to largely or completely replace an earlier revision, such as "delete all existing text, insert new text". In the simplest case, with no branching or undoing, each revision is based on its immediate predecessor alone, and they form a simple line, with a single latest version, the "HEAD" revision or tip. In graph theory terms, drawing each revision as a point and each "derived revision" relationship as an arrow (conventionally pointing from older to newer, in the same direction as time), this is a linear graph. If there is branching, so multiple future revisions are based on a past revision, or undoing, so a revision can depend on a revision older than its immediate predecessor, then the resulting graph is instead a directed tree (each node can have more than one child), and has multiple tips, corresponding to the revisions without children ("latest revision on each branch").[note 3] In principle the resulting tree need not have a preferred tip ("main" latest revision) – just various different revisions – but in practice one tip is generally identified as HEAD. When a new revision is based on HEAD, it is either identified as the new HEAD, or considered a new branch.[note 4] The list of revisions from the start to HEAD (in graph theory terms, the unique path in the tree, which forms a linear graph as before) is the trunk or mainline.[note 5] Conversely, when a revision can be based on more than one previous revision (when a node can have more than one parent), the resulting process is called a merge, and is one of the most complex aspects of revision control. This most often occurs when changes occur in multiple branches (most often two, but more are possible), which are then merged into a single branch incorporating both changes. If these changes overlap, it may be difficult or impossible to merge, and require manual intervention or rewriting.

In the presence of merges, the resulting graph is no longer a tree, as nodes can have multiple parents, but is instead a rooted directed acyclic graph (DAG). The graph is acyclic since parents are always backwards in time, and rooted because there is an oldest version. Assuming there is a trunk, merges from branches can be considered as "external" to the tree – the changes in the branch are packaged up as a patch, which is applied to HEAD (of the trunk), creating a new revision without any explicit reference to the branch, and preserving the tree structure. Thus, while the actual relations between versions form a DAG, this can be considered a tree plus merges, and the trunk itself is a line.

In distributed revision control, in the presence of multiple repositories these may be based on a single original version (a root of the tree), but there need not be an original root - instead there can be a separate root (oldest revision) for each repository. This can happen, for example, if two people start working on a project separately. Similarly, in the presence of multiple data sets (multiple projects) that exchange data or merge, there is no single root, though for simplicity one may think of one project as primary and the other as secondary, merged into the first with or without its own revision history.

Specialized strategies

Engineering revision control developed from formalized processes based on tracking revisions of early blueprints or bluelines[citation needed]. This system of control implicitly allowed returning to an earlier state of the design, for cases in which an engineering dead-end was reached in the development of the design. A revision table was used to keep track of the changes made. Additionally, the modified areas of the drawing were highlighted using revision clouds.

In Business and Law

Version control is widespread in business and law. Indeed, "contract redline" and "legal blackline" are some of the earliest forms of revision control,[10] and are still employed in business and law with varying degrees of sophistication. The most sophisticated techniques are beginning to be used for the electronic tracking of changes to CAD files (see product data management), supplanting the "manual" electronic implementation of traditional revision control.[citation needed]

Source-management models

Traditional revision control systems use a centralized model where all the revision control functions take place on a shared server. If two developers try to change the same file at the same time, without some method of managing access the developers may end up overwriting each other's work. Centralized revision control systems solve this problem in one of two different "source management models": file locking and version merging.

Atomic operations

An operation is atomic if the system is left in a consistent state even if the operation is interrupted. The commit operation is usually the most critical in this sense. Commits tell the revision control system to make a group of changes final, and available to all users. Not all revision control systems have atomic commits; Concurrent Versions System lacks this feature.[11]

File locking

The simplest method of preventing "concurrent access" problems involves locking files so that only one developer at a time has write access to the central "repository" copies of those files. Once one developer "checks out" a file, others can read that file, but no one else may change that file until that developer "checks in" the updated version (or cancels the checkout).

File locking has both merits and drawbacks. It can provide some protection against difficult merge conflicts when a user is making radical changes to many sections of a large file (or group of files). If the files are left exclusively locked for too long, other developers may be tempted to bypass the revision control software and change the files locally, forcing a difficult manual merge when the other changes are finally checked in. In a large organization, files can be left "checked out" and locked and forgotten about as developers move between projects - these tools may or may not make it easy to see who has a file checked out.

Version merging

Most version control systems allow multiple developers to edit the same file at the same time. The first developer to "check in" changes to the central repository always succeeds. The system may provide facilities to merge further changes into the central repository, and preserve the changes from the first developer when other developers check in.

Merging two files can be a very delicate operation, and usually possible only if the data structure is simple, as in text files. The result of a merge of two image files might not result in an image file at all. The second developer checking in the code will need to take care with the merge, to make sure that the changes are compatible and that the merge operation does not introduce its own logic errors within the files. These problems limit the availability of automatic or semi-automatic merge operations mainly to simple text-based documents, unless a specific merge plugin is available for the file types.

The concept of a reserved edit can provide an optional means to explicitly lock a file for exclusive write access, even when a merging capability exists.

Baselines, labels and tags

Most revision control tools will use only one of these similar terms (baseline, label, tag) to refer to the action of identifying a snapshot ("label the project") or the record of the snapshot ("try it with baseline X"). Typically only one of the terms baseline, label, or tag is used in documentation or discussion[citation needed]; they can be considered synonyms.

In most projects, some snapshots are more significant than others, such as those used to indicate published releases, branches, or milestones.

When both the term baseline and either of label or tag are used together in the same context, label and tag usually refer to the mechanism within the tool of identifying or making the record of the snapshot, and baseline indicates the increased significance of any given label or tag.

Most formal discussion of configuration management uses the term baseline.

Distributed revision control

Distributed revision control systems (DRCS) take a peer-to-peer approach, as opposed to the client–server approach of centralized systems. Rather than a single, central repository on which clients synchronize, each peer's working copy of the codebase is a bona-fide repository.[12] Distributed revision control conducts synchronization by exchanging patches (change-sets) from peer to peer. This results in some important differences from a centralized system:

- No canonical, reference copy of the codebase exists by default; only working copies. Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Version_control_software

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk