A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Wellington

Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Māori) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname(s): Windy Wellington, Wellywood | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 41°17′20″S 174°46′38″E / 41.28889°S 174.77722°E | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Wellington |

| Wards |

|

| Community boards | |

| Settled by Europeans | 1839 |

| Named for | A. Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington |

| Electorates | Mana Ōhāriu Rongotai Te Tai Hauāuru (Māori) Te Tai Tonga (Māori) Wellington Central[5] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Tory Whanau |

| • Deputy Mayor | Laurie Foon[6] |

| • MPs | |

| • Territorial authority | Wellington City Council |

| Area | |

| • Territorial | 289.91 km2 (111.93 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 112.36 km2 (43.38 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 177.55 km2 (68.55 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 303.00 km2 (116.99 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 495 m (1,624 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (June 2023)[9] | |

| • Urban | 215,200 |

| • Urban density | 1,900/km2 (5,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 440,900 |

| • Metro density | 1,500/km2 (3,800/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Wellingtonian |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | NZ$ 44.987 billion (2021) |

| • Per capita | NZ$ 82,772 (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| Postcode(s) | 5016, 5028, 6011, 6012, 6021, 6022, 6023, 6035, 6037, 6972[11] |

| Area code | 04 |

| Local iwi | Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Raukawa, Te Āti Awa |

| Website | wellington wellingtonnz.com |

Wellington[b] is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand,[c] and is the administrative centre of the Wellington Region. It is the world's southernmost capital of a sovereign state.[14] Wellington features a temperate maritime climate, and is the world's windiest city by average wind speed.[15]

Māori oral tradition tells that Kupe discovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. The area was initially settled by Māori iwi such as Rangitāne and Muaūpoko. The disruptions of the Musket Wars led to them being overwhelmed by northern iwi such as Te Āti Awa by the early 19th century.[16]

Wellington's current form was originally designed by Captain William Mein Smith, the first Surveyor General for Edward Wakefield's New Zealand Company, in 1840.[17] Smith's plan included a series of interconnected grid plans, expanding along valleys and lower hill slopes.[18] The Wellington urban area, which only includes urbanised areas within Wellington City, has a population of 215,200 as of June 2023.[9] The wider Wellington metropolitan area, including the cities of Lower Hutt, Porirua and Upper Hutt, has a population of 440,900 as of June 2023.[9] The city has served as New Zealand's capital since 1865, a status that is not defined in legislation, but established by convention; the New Zealand Government and Parliament, the Supreme Court and most of the public service are based in the city.[19]

Wellington's economy is primarily service-based, with an emphasis on finance, business services, government, and the film industry. It is the centre of New Zealand's film and special effects industries, and increasingly a hub for information technology and innovation,[20] with two public research universities. Wellington is one of New Zealand's chief seaports and serves both domestic and international shipping. The city is chiefly served by Wellington International Airport in Rongotai, the country's third-busiest airport. Wellington's transport network includes train and bus lines which reach as far as the Kāpiti Coast and the Wairarapa, and ferries connect the city to the South Island.

Often referred to as New Zealand's cultural capital, the culture of Wellington is a diverse and often youth-driven one which has wielded influence across Oceania.[21][22][23] One of the world's most liveable cities, the 2021 Global Livability Ranking tied Wellington with Tokyo as fourth in the world.[24] From 2017 to 2018, Deutsche Bank ranked it first in the world for both livability and non-pollution.[25][26] Cultural precincts such as Cuba Street and Newtown are renowned for creative innovation, "op shops", historic character, and food. Wellington is a leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region, being ranked 35th in the world by the Global Financial Centres Index for 2021. The global city has grown from a bustling Māori settlement, to a colonial outpost, and from there to an Australasian capital that has experienced a "remarkable creative resurgence".[27][28][29][30]

Toponymy

Wellington takes its name from Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington and victor of the Battle of Waterloo (1815): his title comes from the town of Wellington in the English county of Somerset. It was named in November 1840 by the original settlers of the New Zealand Company on the suggestion of the directors of the same, in recognition of the Duke's strong support for the company's principles of colonisation and his "strenuous and successful defence against its enemies of the measure for colonising South Australia". One of the founders of the settlement, Edward Jerningham Wakefield, reported that the settlers "took up the views of the directors with great cordiality and the new name was at once adopted".[31]

In the Māori language, Wellington has three names:

- Te Whanganui-a-Tara, meaning "the great harbour of Tara", refers to Wellington Harbour.[32] The primary settlement of Wellington is said to have been executed by Tara, the son of Whatonga, a chief from the Māhia Peninsula, who told his son to travel south, to find more fertile lands to settle.[33]

- Pōneke, commonly held to be a phonetic Māori transliteration of "Port Nick", short for "Port Nicholson".[34] An alternatively suggested etymology for Pōneke is that it comes from a shortening of the phrase Pō Nekeneke, meaning "journey into the night", referring to the exodus of Te Āti Awa from the Wellington area after they were displaced by the first European settlers.[35][36][37] However, the name Pōneke was already in use by February 1842,[38] earlier than the displacement is said to have happened. The city's central marae, the community supporting it and its kapa haka group have the pseudo-tribal name of Ngāti Pōneke.[39]

- Te Upoko-o-te-Ika-a-Māui, meaning "The Head of the Fish of Māui" (often shortened to Te Upoko-o-te-Ika), a traditional name for the southernmost part of the North Island, deriving from the legend of the fishing up of the island by the demi-god Māui.

The legendary Māori explorer Kupe, a chief from Hawaiki (the homeland of Polynesian explorers, of unconfirmed geographical location, not to be confused with Hawaii), was said to have stayed in the harbour prior to 1000 CE.[33] Here, it is said he had a notable impact on the area, with local mythology stating he named the two islands in the harbour after his daughters, Matiu (Somes Island), and Mākaro (Ward Island).[40]

In New Zealand Sign Language, the name is signed by raising the index, middle, and ring fingers of one hand, palm forward, to form a "W", and shaking it slightly from side to side twice.[41]

The city's location close to the mouth of the narrow Cook Strait leaves it vulnerable to strong gales, leading to the nickname of "Windy Wellington".[42]

History

Māori settlement

Legends recount that Kupe discovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. Before European colonisation, the area in which the city of Wellington would eventually be founded was seasonally inhabited by indigenous Māori. The earliest date with hard evidence for human activity in New Zealand is about 1280.[43]

Wellington and its environs have been occupied by various Māori groups from the 12th century. The legendary Polynesian explorer Kupe, a chief from Hawaiki (the homeland of Polynesian explorers, of unconfirmed geographical location, not to be confused with Hawaii), was said to have stayed in the harbour from c. 925.[44][45] A later Māori explorer, Whatonga, named the harbour Te Whanganui-a-Tara after his son Tara.[46] Before the 1820s, most of the inhabitants of the Wellington region were Whatonga's descendants.[47]

At about 1820, the people living there were Ngāti Ira and other groups who traced their descent from the explorer Whatonga, including Rangitāne and Muaūpoko.[16] However, these groups were eventually forced out of Te Whanganui-a-Tara by a series of migrations by other iwi (Māori tribes) from the north.[16] The migrating groups were Ngāti Toa, which came from Kāwhia, Ngāti Rangatahi, from near Taumarunui, and Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Mutunga, Taranaki and Ngāti Ruanui from Taranaki. Ngāti Mutunga later moved on to the Chatham Islands. The Waitangi Tribunal has found that at the time of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, Te Ātiawa, Taranaki, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāti Tama, and Ngāti Toa held mana whenua interests in the area, through conquest and occupation.[16]

Early European settlement

Steps towards European settlement in the area began in 1839, when Colonel William Wakefield arrived to purchase land for the New Zealand Company to sell to prospective British settlers.[16] Prior to this time, the Māori inhabitants had had contact with Pākehā whalers and traders.[48]

European settlement began with the arrival of an advance party of the New Zealand Company on the ship Tory on 20 September 1839, followed by 150 settlers on the Aurora on 22 January 1840. Thus, the Wellington settlement preceded the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (on 6 February 1840). The 1840 settlers constructed their first homes at Petone (which they called Britannia for a time) on the flat area at the mouth of the Hutt River. Within months that area proved swampy and flood-prone, and most of the newcomers transplanted their settlement across Wellington Harbour to Thorndon in the present-day site of Wellington city.[49]

National capital

Wellington was declared a city in 1840, and was chosen to be the capital city of New Zealand in 1865.[19]

Wellington became the capital city in place of Auckland, which William Hobson had made the capital in 1841. The New Zealand Parliament had first met in Wellington on 7 July 1862, on a temporary basis; in November 1863, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Alfred Domett, placed a resolution before Parliament in Auckland that "... it has become necessary that the seat of government ... should be transferred to some suitable locality in Cook Strait ." There had been some concerns that the more populous South Island (where the goldfields were located) would choose to form a separate colony in the British Empire. Several commissioners (delegates) invited from Australia, chosen for their neutral status, declared that the city was a suitable location because of its central location in New Zealand and its good harbour; it was believed that the whole Royal Navy fleet could fit into the harbour.[50] Wellington's status as the capital is a result of constitutional convention rather than statute.[19]

Wellington is New Zealand's political centre, housing the nation's major government institutions. The New Zealand Parliament relocated to the new capital city, having spent the first ten years of its existence in Auckland.[51] A session of parliament officially met in the capital for the first time on 26 July 1865. At that time, the population of Wellington was just 4,900.[52]

The Government Buildings were constructed at Lambton Quay in 1876. The site housed the original government departments in New Zealand. The public service rapidly expanded beyond the capacity of the building, with the first department leaving shortly after it was opened; by 1975 only the Education Department remained, and by 1990 the building was empty. The capital city is also the location of the highest court, the Supreme Court of New Zealand, and the historic former High Court building (opened 1881) has been enlarged and restored for its use. The Governor-General's residence, Government House (the current building completed in 1910) is situated in Newtown, opposite the Basin Reserve. Premier House (built in 1843 for Wellington's first mayor, George Hunter), the official residence of the prime minister, is in Thorndon on Tinakori Road.

Over six months in 1939 and 1940, Wellington hosted the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition, celebrating a century since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Held on 55 acres of land at Rongotai, it featured three exhibition courts, grand Art Deco-style edifices and a hugely popular three-acre amusement park. Wellington attracted more than 2.5 million visitors at a time when New Zealand's population was 1.6 million.[53]

Geography

Wellington is at the south-western tip of the North Island on Cook Strait, separating the North and South Islands. On a clear day, the snowcapped Kaikōura Ranges are visible to the south across the strait. To the north stretch the golden beaches of the Kāpiti Coast. On the east, the Remutaka Range divides Wellington from the broad plains of the Wairarapa, a wine region of national notability.

With a latitude of 41° 17' South, Wellington is the southernmost capital city in the world.[54] Wellington ties with Canberra, Australia, as the most remote capital city, 2,326 km (1,445 mi) apart from each other.

Wellington is more densely populated than most other cities in New Zealand due to the restricted amount of land that is available between its harbour and the surrounding hills. It has very few open areas in which to expand, and this has brought about the development of the suburban towns. Because of its location in the Roaring Forties and its exposure to the winds blowing through Cook Strait, Wellington is the world's windiest city, with an average wind speed of 27 km/h (17 mph).[55]

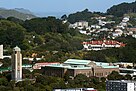

Wellington's scenic natural harbour and green hillsides adorned with tiered suburbs of colonial villas are popular with tourists. The central business district (CBD) is close to Lambton Harbour, an arm of Wellington Harbour, which lies along an active geological fault, clearly evident on its straight western shore. The land to the west of this rises abruptly, meaning that many suburbs sit high above the centre of the city. There is a network of bush walks and reserves maintained by the Wellington City Council and local volunteers. These include Otari-Wilton's Bush, dedicated to the protection and propagation of native plants. The Wellington region has 500 square kilometres (190 sq mi) of regional parks and forests. In the east is the Miramar Peninsula, connected to the rest of the city by a low-lying isthmus at Rongotai, the site of Wellington International Airport. Industry has developed mainly in the Hutt Valley, where there are food-processing plants, engineering industries, vehicle assembly and oil refineries.[56]

The narrow entrance to the harbour is to the east of the Miramar Peninsula, and contains the dangerous shallows of Barrett Reef, where many ships have been wrecked (notably the inter-island ferry TEV Wahine in 1968).[57] The harbour has three islands: Matiu/Somes Island, Makaro/Ward Island and Mokopuna Island. Only Matiu/Somes Island is large enough for habitation. It has been used as a quarantine station for people and animals, and was an internment camp during World War I and World War II. It is a conservation island, providing refuge for endangered species, much like Kapiti Island farther up the coast. There is access during daylight hours by the Dominion Post Ferry.

Wellington is primarily surrounded by water, but some of the nearby locations are listed below.

Geology

Wellington suffered serious damage in a series of earthquakes in 1848[58] and from another earthquake in 1855. The 1855 Wairarapa earthquake occurred on the Wairarapa Fault to the north and east of Wellington. It was probably the most powerful earthquake in recorded New Zealand history,[59] with an estimated magnitude of at least 8.2 on the Moment magnitude scale. It caused vertical movements of two to three metres over a large area, including raising land out of the harbour and turning it into a tidal swamp. Much of this land was subsequently reclaimed and is now part of the central business district. For this reason, the street named Lambton Quay is 100 to 200 metres (325 to 650 ft) from the harbour – plaques set into the footpath mark the shoreline in 1840, indicating the extent of reclamation. The 1942 Wairarapa earthquakes caused considerable damage in Wellington.

The area has high seismic activity even by New Zealand standards, with a major fault, the Wellington Fault, running through the centre of the city and several others nearby. Several hundred minor faults lines have been identified within the urban area. Inhabitants, particularly in high-rise buildings, typically notice several earthquakes every year. For many years after the 1855 earthquake, the majority of buildings were made entirely from wood. The 1996-restored Government Buildings[60] near Parliament is the largest wooden building in the Southern Hemisphere. While masonry and structural steel have subsequently been used in building construction, especially for office buildings, timber framing remains the primary structural component of almost all residential construction. Residents place their confidence in good building regulations, which became more stringent in the 20th century. Since the Canterbury earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, earthquake readiness has become even more of an issue, with buildings declared by Wellington City Council to be earthquake-prone,[61][62] and the costs of meeting new standards.[63][64]

Every five years, a year-long slow quake occurs beneath Wellington, stretching from Kapiti to the Marlborough Sounds. It was first measured in 2003, and reappeared in 2008 and 2013.[65] It releases as much energy as a magnitude 7 quake, but as it happens slowly, there is no damage.[66]

During July and August 2013 there were many earthquakes, mostly in Cook Strait near Seddon. The sequence started at 5:09 pm on Sunday 21 July 2013 when the magnitude 6.5 Seddon earthquake hit the city, but no tsunami report was confirmed nor any major damage.[67] At 2:31 pm on Friday 16 August 2013 the Lake Grassmere earthquake struck, this time magnitude 6.6, but again no major damage occurred, though many buildings were evacuated.[68] On Monday 20 January 2014 at 3:52 pm a rolling 6.2 magnitude earthquake struck the lower North Island 15 km east of Eketāhuna and was felt in Wellington, but little damage was reported initially, except at Wellington Airport where one of the two giant eagle sculptures commemorating The Hobbit became detached from the ceiling.[69][70]

At two minutes after midnight on Monday 14 November 2016, the 7.8 magnitude Kaikōura earthquake, which was centred between Culverden and Kaikōura in the South Island, caused the Wellington CBD, Victoria University of Wellington, and the Wellington suburban rail network to be largely closed for the day to allow inspections. The earthquake damaged a considerable number of buildings, with 65% of the damage being in Wellington. Subsequently, a number of recent buildings were demolished rather than being rebuilt, often a decision made by the insurer. Two of the buildings demolished were about eleven years old – the seven-storey NZDF headquarters[71][72] and Statistics House at Centreport on the waterfront.[73] The docks were closed for several weeks after the earthquake.[74]

Relief

Steep landforms shape and constrain much of Wellington city. Notable hills in and around Wellington include:

- Mount Victoria – 196 m. Mt Vic is a popular walk for tourists and Wellingtonians alike, as from the summit one can see most of Wellington. There are numerous mountain bike and walking tracks on the hill.

- Mount Albert[75] – 178 m

- Mount Cook

- Mount Alfred (west of Evans Bay)[76] – 122 m

- Mount Kaukau – 445 m. Site of Wellington's main television transmitter.

- Mount Crawford[77]

- Brooklyn Hill – 299 m

- Wrights Hill

- Mākara Peak – summit (412 m) is within the 250 ha Makara Peak Mountain Bike Park that includes 45 km of trails[78]

- Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori) Hill

Climate

Averaging 2,055 hours of sunshine per year, the climate of Wellington is temperate marine, (Köppen: Cfb), generally moderate all year round with warm summers and mild winters, and rarely sees temperatures above 26 °C (79 °F) or below 4 °C (39 °F). The hottest recorded temperature in the city is 31.1 °C (88 °F) recorded on 20 February 1896[citation needed], while −1.9 °C (29 °F) is the coldest.[79] The city is notorious for its southerly blasts in winter, which may make the temperature feel much colder. It is generally very windy all year round with high rainfall; average annual rainfall is 1,250 mm (49 in), June and July being the wettest months. Frosts are quite common in the hill suburbs and the Hutt Valley between May and September. Snow is very rare at low altitudes, although snow fell on the city and many other parts of the Wellington region during separate events on 25 July 2011 and 15 August 2011.[80][81] Snow at higher altitudes is more common, with light flurries recorded in higher suburbs every few years.[82]

On 29 January 2019, the suburb of Kelburn (instruments near the Metservice building in the Wellington Botanic Garden) reached 30.3 °C (87 °F), the highest temperature since records began in 1927.[83]

| Climate data for Wellington (Kelburn) (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.1 (84.4) |

30.3 (86.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

0.2 (32.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 79.2 (3.12) |

55.5 (2.19) |

99.6 (3.92) |

126.7 (4.99) |

144.9 (5.70) |

123.8 (4.87) |

147.1 (5.79) |

139.1 (5.48) |

108.0 (4.25) |

118.7 (4.67) |

85.4 (3.36) |

91.1 (3.59) |

1,319.1 (51.93) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.9 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 13.4 | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Wellington,_New_Zealand|||||||