A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (December 2023) |

Sir William Robertson | |

|---|---|

Robertson in 1915 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Wully" |

| Born | 29 January 1860 Welbourn, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 12 February 1933 (aged 73) London, England |

| Buried | Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey, England |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1877–1920 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Unit | 16th The Queen's Lancers |

| Commands held | British Army of the Rhine Eastern Command Chief of the Imperial General Staff Staff College, Camberley |

| Battles/wars | Chitral Expedition Second Boer War First World War |

| Awards | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Distinguished Service Order Mentioned in Despatches Order of the White Eagle[1] |

Field Marshal Sir William Robert Robertson, 1st Baronet, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, DSO (29 January 1860 – 12 February 1933) was a British Army officer who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) – the professional head of the British Army – from 1916 to 1918 during the First World War.

As CIGS he was committed to a Western Front strategy focusing on Germany. He had increasingly poor relations with David Lloyd George, Secretary of State for War and then Prime Minister, and threatened resignation at Lloyd George's attempt to subordinate the British forces to the French Commander-in-Chief, Robert Nivelle. In 1917 Robertson supported the continuation of the Battle of Passchendaele at odds with Lloyd George's view that Britain's war effort ought to be focused on the other theatres until the arrival of sufficient US troops on the Western Front.[2] Robertson is the only soldier in the history of the British Army to have risen from an enlisted rank to its highest rank of field marshal.[2]

Early life

Robertson was born in Welbourn, Lincolnshire, the son of Thomas Charles Robertson, a tailor and postmaster, and Ann Dexter Robertson (née Beet).[3] He was educated at the local church school and later earned 6d a week as a pupil-teacher. After leaving school in 1873, he became a garden boy in the village rectory, then in 1875 he became a footman in the Countess of Cardigan's[4] household at Deene Park. He made no mention of this period in his life in his autobiography and seldom spoke of it.[5]

He began his military career in November 1877 by enlisting for twelve years as a trooper in the 16th (The Queen's) Lancers.[2][6] As he was three months short of the official minimum age of eighteen, at the behest of the recruiting sergeant he declared his age as eighteen years and two months, these extra five months becoming his "official" age throughout his time in the Army.[7]

His mother wrote to him in horror:

You know you are the Great Hope of the Family...if you do not like Service you can do something else...there are plenty of things Steady Young Men can do when they can write and read as you can...(the Army) is a refuge for all idle people...I shall name it to no one for I am ashamed to think of it...I would rather bury you than see you in a red coat.[2][8][9]

On his first night in the Army, he was so horrified by the rowdiness of the barrack room that he contemplated deserting, only to find that his civilian clothes had been stolen by another deserter.[10]

As a young soldier, Robertson was noted for his prowess at running and for his voracious reading of military history. He won company first prizes for sword, lance and shooting.[6] Among the young lieutenants under whom he served were future Lieutenant-General "Jimmy" Babington and "Freddy" Blair, who would later be Robertson's Military Secretary at Eastern Command in 1918.[11] He was promoted to lance-corporal in February 1879 and corporal in April 1879.[11] As a corporal, he was imprisoned for three weeks with his head shaven when a soldier under arrest, whom he was escorting, escaped near Waterloo Station. Later, whilst serving in Ireland, he once kept soldiers under arrest handcuffed for a twelve-hour train journey rather than risk a repetition of the event.[12]

He was promoted to lance-sergeant in May 1881 and sergeant in January 1882.[11] He obtained a first class certificate of education in 1883, while serving in Ireland.[13] Robertson was promoted to troop sergeant major in March 1885 to fill a vacancy, as his predecessor, a former medical student serving in the ranks, had been demoted for making a botch of the regimental accounts and later committed suicide.[2][11][14]

Junior officer

Encouraged by his officers, and the clergyman of his old parish,[6][15] he passed an examination for an officer's commission and was posted as a second lieutenant in the 3rd Dragoon Guards on 27 June 1888.[6][16] Robertson later recorded that it would have been impossible to live as a cavalry subaltern in Britain, where £300 a year was needed in addition to the £120 official salary (approximately £30,000 and £12,000 at 2010 prices) to keep up the required lifestyle; he was reluctant to leave the cavalry,[17] but his regiment was deployed to India, where pay was higher and expenses lower than in the UK. Robertson's father made his uniforms and he economised by drinking water with meals and not smoking, as pipes were not permitted in the mess and he could not afford the cigars which officers were expected to smoke. Robertson supplemented his income by studying with native tutors, qualifying as an interpreter—for which officers received cash grants—in Urdu, Hindi, Persian, Pashto and Punjabi.[2][18]

Promoted to lieutenant on 1 March 1891,[19] he saw his first active service in 1891, distinguishing himself as Railway Transport Officer for the expedition to Kohat.[20] He was appointed an attaché in the Intelligence Branch of the Quartermaster-General's Department at Simla in India on 5 June 1892.[21] There he became a protégé of Sir Henry Brackenbury, the new Military Member of the Viceroy's Council (equivalent to War Minister for India), who had been Director of Military Intelligence in London and was keen to beef up the intelligence branch of the Indian army, including mapping the Northwest Frontier. Robertson spent a year writing a long and detailed Gazetteer and Military Report on Afghanistan.[20] After five years in India he was granted his first long leave in 1893, only to find that his mother had died before he reached home.[22]

In June 1894 he undertook a three-month journey via Gilgit and mountainous north Kashmir, crossing the Darkot Pass at over 4,700 metres (15,430 ft) to reach the Pamirs Plateau at the foot of the Himalayas, returning to India in August by a westerly route via Chilas and Khagan. On the journey he learned Gurkhali, later qualifying in this, his sixth Indian language.[20]

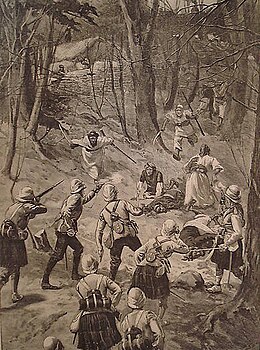

He was promoted to captain on 3 April 1895.[23] He took part in the Chitral Expedition as Brigade Intelligence Officer to the force which marched through the Malakand Pass, across the Swat River, via Dir to Chitral. He was described by Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Low, the Expedition Commander, as a "very active and intelligent officer of exceptional promise".[24][25] After the relief of Chitral and installation of Shuja-ul-Mulk as Mehtar, Robertson was engaged in pacification and reconnaissance duties, but was wounded when attacked by his two guides on a narrow mountain path during a reconnaissance. One guide was armed with a shotgun and fired at Robertson but missed. The other guide attacked him with Robertson's own sword (which he had been carrying, as Robertson had dysentery) but Robertson punched him to the ground then drove off both attackers with his revolver; one was wounded and later captured and executed.[26] The incident was reported and illustrated in the Daily Graphic[26] and Robertson was awarded the DSO,[27] which was, he later recorded, "then a rather rare decoration".[24]

Staff College

Robertson then applied to attend Staff College, Camberley. Unlike most applicants, he could not afford to take extended leave from his job (on the intelligence staff at Simla) to attend a crammer, and had he failed he would have been too old to apply again, so he rose between 4 and 5 am each day to study mathematics, German, and French with the assistance of his wife. He later qualified as an interpreter in French. He just missed a place, but was given a nominated place on the recommendation of Sir George White (Commander-in-Chief, India). In 1897, accompanied by his wife and baby son, he became the first former ranker to go there.[2][18][28]

Under George Henderson he absorbed the principles, derived from Jomini, Clausewitz, and Edward Hamley's Operations of War (1866), of concentration of physical and moral force and the destruction of the main enemy army.[18] He passed out second from Staff College in December 1898[15] and was then seconded for service in the Intelligence Department at the War Office on 1 April 1899.[29] As a staff captain he was the junior of two officers in the Colonial (later renamed Imperial) section.[30]

Boer War and War Office

With the start of the Second Boer War, Robertson was appointed as Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General to Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, the British Commander-in-Chief South Africa, on 15 January 1900.[31] He was present at the Battle of Paardeberg (17–26 February 1900), the Battle of Poplar Grove (7 March 1900) and other battles in March and May.[15] Robertson was promoted to major on 10 March 1900[32] and was mentioned in despatches on 2 April 1901.[33]

He returned to the War Office in October 1900 and on 29 November 1900 was promoted brevet lieutenant-colonel for his services in South Africa.[15][34] On 1 October 1901 he was appointed Assistant Quartermaster-General, responsible for the Foreign Military Intelligence section, on the recommendation of the Intelligence expert General Sir Henry Brackenbury,[30][35] and worked closely with William Nicholson (then Director of Military Operations).[15] Although Robertson was later to be a staunch advocate of Britain's concentration of effort on the Western Front, in March 1902 (before the Entente Cordiale) he wrote a paper recommending that, in the event of Belgian neutrality being violated, Britain should concentrate on naval warfare and deploy no more troops to Belgium than was needed to "afford ocular proof[36] of our share in the war". His suggestion did not meet with approval at the highest political level.[37]

Robertson was promoted to brevet colonel on 29 November 1903.[38] Having been one of the oldest lieutenants in the army, he was now one of the youngest colonels, heading a staff of nine officers. In the later words of a contemporary, Robertson "became rated as a superman, and only key appointments were considered good enough for him".[30]

Robertson was made Assistant Director of Military Operations under James Grierson and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) on 30 June 1905.[39] In spring 1905, during the First Moroccan Crisis, Grierson and Robertson conducted a war game based on a German march through Belgium, Robertson commanding the German forces. They were persuaded that early and strong British intervention – it was assumed that British forces would land at Antwerp – was necessary to slow the German advance and avoid French defeat.[40][41] In 1906 they toured the Charleroi-to-Namur area with the French liaison officer Victor Huguet.[40] In 1906 Robertson also toured the Balkans, where he was impressed by the size of the mountains, a factor which was later to influence his scepticism about the Salonika front during the First World War.[42]

When that job expired in January 1907, Robertson, without a post, was placed on so-called half-pay. In fact, his salary dropped from £800 to £300, causing him severe financial difficulty; he earned money by translating German and Austro-Hungarian military manuals into English, again assisted by his wife.[15][43] He became Assistant Quartermaster-General at Headquarters Aldershot Command on 21 May 1907[44] and then brigadier general (equivalent to the modern rank of brigadier) on the General Staff at Headquarters Aldershot Command on 29 November 1907.[45] He had hoped for command of a brigade.[46] In 1909 he reconnoitred the likely route of a German invasion – Belgium, the Meuse and Luxembourg – with Smith-Dorrien and Rawlinson.[47]

Commandant, Staff College

During Henry Wilson's tenure as Commandant at Staff College, Camberley (1906–10), Robertson lectured on Belgium, the Canadian frontier and the Balkans.[48]

Robertson's patron Nicholson, now Chief of the Imperial General Staff, appointed[15] him Commandant at Staff College, effective 1 August 1910.[49] However, Nicholson had initially (according to Wilson) opposed Robertson "because of want of breeding", while Wilson also opposed Robertson's appointment, perhaps feeling that Robertson's lack of private means did not suit him for a position which required entertaining. Robertson wrote to his friend Godley of a "pestilential circle" in top appointments which left "no chance for the ordinary man". On 28 July 1910, shortly before taking up his new position, Robertson visited Camberley with Kitchener, who criticised Wilson. Relations between Wilson and Robertson deteriorated thereafter, beginning a rivalry which was to feature throughout the Great War.[50]

Robertson was a practical lecturer at Camberley whose teaching included withdrawals as well as advances. Edmonds, who had been Robertson's classmate in the 1890s, said he was a better lecturer than even Henderson.[51] He taught officers that they "were at the Staff College to learn Staff Duties and to qualify for Staff Captain, not to talk irresponsible trash" about "subjects of policy or strategy".[52] These and a number of similar recollections, written up after the Great War, may exaggerate the differences in style between Robertson and Wilson.[53]

He was appointed a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order on 16 July 1910[54] and promoted to major-general on 26 December 1910.[55][56] He was advanced to Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order on 26 September 1913;[57] on being knighted he mistakenly rose and shook the King's proffered hand instead of kissing it as required by protocol. The King was privately amused and the two men soon formed a good relationship.[58] He was appointed Director of Military Training at the War Office on 9 October 1913.[59]

Curragh incident

With the Cabinet apparently contemplating some kind of military action against the Ulster Volunteers, on the evening of 18 March, Robertson was told that it was his responsibility as DMT to draw up deployment plans.[60] After Hubert Gough and other officers had threatened to resign in the Curragh incident, Robertson also supported Wilson in trying in vain to persuade French (CIGS) to warn the government that the Army would not move against Ulster.[61] The affair led to hatred between senior officers and Liberal politicians. Robertson contemplated resigning, but unlike French or Wilson he emerged without any blot on his reputation.[51]

First World War: 1914–15

Quartermaster General, BEF

Robertson was expected to remain Director of Military Training on the outbreak of the First World War, or to become chief staff officer to the Home Defence Forces.[62] Instead he replaced Murray as Quartermaster General of the British Expeditionary Force (under Field Marshal French) from 5 August 1914.[63]

Robertson was concerned that the BEF was concentrating too far forward, and discussed a potential retreat as early as 22 August (the day before the Battle of Mons).[64] He arranged supply dumps and contingency plans to draw supply from the Atlantic rather than the Belgian coast, all of which proved invaluable during the retreat from Mons. He became known as "Old Any-Complaints?" as this was his usual question when checking on troops at mealtimes.[51] In Dan Todman's view, the excellent performance of BEF logistics in August 1914 contrasted favourably with the "almost farcical" performance of the BEF General Staff.[65]

Robertson "felt deeply" the loss of his close friend Colonel Freddy Kerr, who was killed by a shell while serving as GSO1 (chief of staff) to 2nd Division.[66][67]

Robertson was then promoted (over the head of Wilson who was already Sub Chief of Staff) to Chief of Staff (CGS) of the BEF from 25 January 1915.[68] Robertson had told Wilson that he did not want the promotion as he "could not manage Johnnie, who was sure to come to grief and carry him along with him". Robertson later wrote that he had hesitated to accept the job, despite the higher pay and position, as he knew he was not French's first choice, but had put his duty first. He refused to have Wilson remain as Sub Chief. French was soon impressed by Robertson's "sense and soundness" as CGS.[69][70] Wilson continued to advise French closely whereas Robertson took his meals in a separate mess. Robertson preferred this, and in common with many other senior BEF officers his relations with French deteriorated badly in 1915.[71]

Chief of Staff, BEF

Robertson improved the functioning of the staff at GHQ by separating Staff Duties and Intelligence out from Operations into separate sections, each headed by a Brigadier-General reporting to himself.[65] Robertson was advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath on 18 February 1915.[72]

Robertson consistently urged strong commitment to the Western Front. He thought the naval attempt to force the Dardanelles "a ridiculous farce".[a] Robertson told Hankey on 1 June that Sir John French was "always wanting to do reckless and impossible things" and made similar remarks to Kitchener in July.[74] He advised on 25 June 1915 against retreat to the Channel Ports, an option contemplated by the Cabinet after the defensive losses at Second Ypres, arguing that it would leave the British "helpless spectators" in France's defeat, and on 26 June, in response to a Churchill memorandum, that attacks on entrenched positions at Gallipoli had been just as costly as on the Western Front, but without the chance of defeating the German army. In "Notes on the Machinery of the Government for the Conduct of the War" on 30 June 1915 he argued, in Clausewitzian terms, that the government should state its war aims, in this case, the liberation of Belgium and the destruction of German militarism, and then let the professionals achieve them.[75]

The King had a "long talk" with Robertson on 1 July and was left convinced that French should be removed as Commander-in-Chief of the BEF.[76] Attending a council of war in London in early July 1915, Robertson was asked at the end if he had any comments—he produced a map and delivered a 45-minute lecture, and when interrupted stood glaring at the minister. His presentation made a strong impression compared to the indecisiveness of the politicians and Kitchener.[77]

Robertson wrote to Kiggell (20 June 1915) that "these Germans are dug in up to the neck, or concreted" in "one vast fortress".[78] Tactically, he urged "slow attrition, by a slow and gradual advance on our part, each step being prepared by a predominant artillery fire and great expenditure of ammunition" and stressed the importance of counterbattery work. He also (July 1915) advocated surprise, and realistic objectives to prevent attacking infantry outrunning their artillery cover and ragged lines becoming vulnerable to German counterattack. Maurice, who drafted many of Robertson's memos, had advised him that such attacks were best carried out in places where the Germans were, for political or strategic reasons, reluctant to retreat so were bound to take heavy losses.[79] Robertson initially opposed the mooted Loos offensive, recommending a more limited attack by Second Army to seize Messines-Wyndeschete ridge, and telling Sidney Clive it would be "throwing away thousands of lives in knocking our heads against a brick wall".[80][81] He tried to get Sir John "in a better state of mind & not so ridiculously optimistic about a state of German collapse", although he told a conference in July that he and Sir John French "looked out above all things for optimists".[82]

Robertson also advised (5 August) that Russia, then being driven out of Poland, might make peace without a wholehearted British commitment.[83]

Robertson complained to Wilson (29 July) that French "chopped & changed every day & was quite hopeless" and (12 August) was "very sick with Sir J., he cannot manage him nor influence him"; Wilson noted that relations between French and Robertson were breaking down, and suspected (correctly) that Robertson was blackening French's reputation by sending home documents which French had refused to read or sign.[76] He wrote a memo to French (3 or 5 August) arguing that the volunteer New Armies should be committed to the Western Front, an idea to which Kitchener was only reluctantly coming round. French refused to read it, explaining that he was "fully acquainted with the situation", so Robertson sent it to the King's adviser Wigram anyway.[71]

Robertson was made a Grand Officer of the French Legion of Honour on 10 September 1915[84] and acted as Commander-in-Chief BEF when French was sick in September.[85]

Promotion to CIGS

Robertson later wrote in his memoirs that he was not close to Kitchener, having only ever served with him in South Africa. With Asquith's Coalition Government in danger of breaking up over conscription (which Robertson supported), he blamed Kitchener for the excessive influence which civilians like Churchill and Haldane had come to exert over strategy, allowing ad hoc campaigns to develop in Sinai, Mesopotamia and Salonika, and not asking the General Staff to study the feasibility of any of these campaigns. Robertson had urged the King's adviser Stamfordham that a stronger General Staff was needed in London, otherwise "disaster" would ensue. By October 1915 Robertson had come to support greater coordination of plans with the French and was in increasingly close touch with Charles Callwell, who had been recalled from retirement to become Director of Military Operations.[86]

When the King toured the front (24 October) Haig told him that Robertson should go home and become CIGS,[76] while Robertson told the King (27 October 1915) that Haig should replace French.[87] He was promoted to permanent lieutenant general on 28 October 1915.[88] Robertson clinched his claim as the future CIGS with a lengthy paper (actually written by Maurice, dated 8 November) arguing that all British efforts must be directed at the defeat of Germany.[89]

French, finally forced to "resign" early in December 1915, recommended Robertson as his successor and Kitchener told Esher (4 December) that the government intended to appoint Robertson Commander-in-Chief, although to Esher's disappointment "dear old R" was not appointed. Robertson was willing to relinquish his claim if the job went to Haig, his senior and a front line commander since the start of the war. Haig's inarticulacy may also have made him an unappealing choice as CIGS.[85]

Kitchener and Asquith were agreed that Robertson should become CIGS, but Robertson refused to do this if Kitchener "continued to be his own CIGS", although given Kitchener's great prestige he wanted him not to resign but to be sidelined to an advisory role like the Prussian War Minister. Asquith asked the men to negotiate an agreement, which they did over the exchange of several draft documents at the Hotel de Crillon in Paris. Kitchener agreed that Robertson alone should present strategic advice to the Cabinet, with Kitchener responsible for recruiting and supplying the Army, and that the Secretary of State should sign orders jointly with the CIGS (Robertson had demanded that orders go out over his signature alone).[90] Robertson became Chief of the Imperial General Staff on 23 December 1915,[91] with an Order in Council formalising Kitchener and Robertson's relative positions in January 1916.[90]

Initial decisions

Robertson assumed his duties on 23 December 1915. He brought with him three able men from GHQ: Whigham (Robertson's Deputy), Maurice (Operations) and MacDonogh (Intelligence). Their replacements, especially Kiggell (the new CGS BEF), and Charteris (BEF Intelligence) were much less able than their predecessors, a fact which probably affected BEF performance over the next two years.[92]

Although Robertson's advice to abandon the Salonika bridgehead had been overruled at the Allied Chantilly Conference (6–8 December 1915), his first act as CIGS was to insist on the evacuation of the Cape Helles bridgehead, which the Royal Navy had wanted to retain as a base and which some (e.g. Balfour, Hankey) had wanted to retain for the sake of British prestige in the Middle East (abandonment of the other Gallipoli bridgehead at Suvla/Anzac, too narrow to defend against enemy artillery, had already been decided on 7 December).[93]

On his first day as CIGS Robertson also demanded a defensive policy in Mesopotamia, with reinforcements drawn only from India – this was agreed on 29 February 1916, over the objections of Balfour and Lloyd George. Robertson also insisted that Mesopotamian operations (and eventually logistics as well) be brought under his control rather than that of the India Office. Townshend, besieged in Kut, was not initially thought to be in danger, but eventually surrendered in April 1916 after three failed relief attempts.[94]

Another early act as CIGS (27 December 1915) was to press Kitchener for an extra 18 divisions for the BEF. Conscription of bachelors – for which Robertson lobbied – was enacted in early 1916.[95]

CIGS: 1916

Strategic debates

Robertson was a strong supporter of BEF commander Douglas Haig and was committed to a Western Front strategy focusing on Germany and was against what he saw as peripheral operations on other fronts.[2]

Having seen politicians like Lloyd George and Churchill run rings around Kitchener, Robertson's policy was to present his advice and keep on repeating it, refusing to enter into debate. However, Robertson reduced the government's freedom of action by cultivating the press, much of which argued that the professional leadership of Haig and Robertson was preferable to civilian interference which had led to disasters like Gallipoli and Kut. He was particularly close to H. A. Gwynne and Charles Repington, who worked for the Northcliffe Press until it ceased to support the generals late in 1917, and advised Haig to cultivate journalists also. Robertson communicated by secret letters and "R" telegrams to generals in the field,[96] including Milne, whom he discouraged from offensive operations at Salonika,[97] and Maude who may have "consciously or unconsciously" ignored his secret orders from Robertson not to attempt to take Baghdad.[98]

In a 12 February 1916 paper Robertson urged that the Allies offer a separate peace to Turkey, or else offer Turkish territory to Bulgaria to encourage Bulgaria to make peace. In reply, Grey pointed out that Britain needed her continental allies more than they needed her, and Britain could not risk them making a compromise peace which left Germany stronger on the continent.[75]

Robertson told the War Committee (22 February 1916) that the French desire to transfer more troops to Salonika showed a weakening in their resolve for trench warfare. He scorned the idea that it would bring Greece into the war on the Allied side, and at a late March 1916 conference argued with Briand (French Prime Minister) and Joffre, who thumped the table and shouted that Robertson was "un homme terrible".[99][100]

The War Committee had only agreed (28 December 1915) with some reluctance to make preparations for the Western Front Offensive agreed at Chantilly, which Haig and Joffre agreed (14 February) should be on the Somme, although Robertson and the War Committee were not pleased at Joffre's suggestion that the British engage in "wearing out" attacks prior to the main offensive. For three months, against a backdrop of Russia planning to attack earlier than agreed, Italy reluctant to attack at all and the scaling-down of the planned French commitment because of Battle of Verdun, Robertson continued to urge the politicians to agree to the offensive. He increasingly believed that France was becoming exhausted and that Britain would carry an ever greater burden. After Robertson promised that Haig "would not make a fool of himself" (he told Repington that Haig was "a shrewd Scot who would not do anything rash"), the War Committee finally agreed (7 April).[101]

Robertson lobbied hard with politicians and the press for the extension of conscription. When the Cabinet finally authorised the Somme Offensive, Robertson had the Army Council make a statement in favour of conscripting married men. In the face of protests from Bonar Law that the government might break up, to be followed by a General Election (which he thought would be divisive, even though the Conservatives would probably win) and conscription brought in by martial law, Robertson refused to compromise and encouraged Dawson, editor of The Times, to make his stance public.[95] After poor relations between French and Kitchener had permitted civilian interference in strategy, Robertson was also determined to stand solid with Haig, telling him (26 April 1916) that they finally had the civilians "into a corner & have the upper hand".[96]

Prelude to the Somme

Robertson was contemptuous of the House Grey Memorandum (early 1916) and of President Woodrow Wilson's offer to mediate in May 1916. The plan was stopped when the entire Army Council, including Kitchener and Robertson, threatened to resign.[102]

At first Robertson tried to limit information to the War Committee only to a summary of news, most of which had already appeared in the newspapers – this was stopped by Hankey and Lloyd George when it was discovered that Robertson had moved troops from Egypt and Britain to France with little reference to the War Committee. (Given the logistical difficulties, Robertson scoffed at suggestions that the Turks might invade Egypt, and by July, on his orders, Murray had shipped out 240,000 of the 300,000 British Empire troops in Egypt, most of them going to France[103]) In late May Haig and Robertson also angered ministers by challenging their right to inquire into the shipping of animal fodder to France.[96]

Robertson told ministers that "Haig had no idea of any attempt to break through the German lines. It would only be a move to (rescue) the French", although he was probably not aware of Haig's insistence, overruling Rawlinson's earlier plan, on bombarding deeper into the German defences in the hope of breaking through and "fighting the enemy in the open".[104]

Robertson was promoted to permanent general on 3 June 1916.[105] At an Anglo-French conference at 10 Downing Street Robertson finally succeeded in blocking a major offensive from Salonika.[106] Robertson lobbied hard but in vain to prevent Lloyd George, who made no secret of his desire to use his control over military appointments to influence strategy, from succeeding Kitchener as Secretary of State for War. Although Robertson retained the special powers he had been granted in December 1915, and Lord Derby, an ally of the soldiers, was appointed Under-Secretary, Robertson still wrote to Kiggell "That d----d fellow L.G. is coming here I fear. I shall have an awful time".[107]

The Somme

Robertson had been clear that it would take more than one battle to defeat Germany, but like many British generals he overestimated the chances of success on the Somme.[108] Robertson also wrote to Kiggell (Chief of Staff BEF) stressing that "the road to success lies through deliberation". He recommended "concentration and not dispersion of artillery fire" and "the thing is to advance along a wide front, step by step to very limited and moderate objectives, and to forbid going beyond those objectives until all have been reached by the troops engaged".[109][110][111]

Kiggell conceded that there had been problems with infantry-artillery coordination, but seemed more concerned with the slowness of progress.[111] Possibly (in David Woodward's view) worried at Kiggell's response, Robertson wrote to Rawlinson, GOC Fourth Army, on 26 July urging him not to let the Germans "beat you in having the better man-power policy" and urging "common-sense, careful methods, and not to be too hide-bound by the books we used to study before the war".[109][112]

Henry Wilson recorded rumours that Robertson was angling for Haig's job in July,[113] although there is no clear evidence that this was so.[114] Robertson complained that Haig's daily telegrams to him contained little more information than the daily press releases. F. E. Smith (1 August) circulated a paper by his friend Winston Churchill (then out of office), criticising the high losses and negligible gains of the Somme. Churchill argued that this would leave Germany freer to win victories elsewhere. Robertson issued a strong rebuttal the same day, arguing that Britain's losses were small compared to what France had suffered in previous years, that Germany had had to quadruple the number of her divisions on the Somme sector and that this had taken pressure off Verdun and contributed to the success of Russian and Italian offensives.[114]

After the Churchill memorandum Robertson wrote to Haig accusing the War Committee (a Cabinet committee which discussed strategy in 1916) of being "ignorant" and putting too much emphasis on "gaining ground" rather than putting "pressure" on the Germans; Travers argues that he was "cunning(ly)” using the War Committee as "a stalking horse" and obliquely urging Haig to adopt more cautious tactics.[115] Both Robertson and Esher wrote to Haig reminding him of how Robertson was covering Haig's back in London, Robertson reminding Haig of the need to give him "the necessary data with which to reply to the swines" (7 and 8 August).[114]

With Allied offensives apparently making progress on all fronts in August, Robertson hoped that Germany might sue for peace at any time and urged the government to pay more attention to drawing up war aims, lest Britain get a raw deal in the face of collusion between France and Russia. Prompted by Asquith, Robertson submitted a memorandum on war aims (31 August). He wanted Germany preserved as a major power as a block to Russian influence, possibly gaining Austria to compensate for the loss of her colonies, Alsace-Lorraine and her North Sea and Baltic ports.[116]

Clash with Lloyd George

Robertson correctly guessed that the Bulgarian declaration of war on Romania (1 September) indicated that they had been promised German aid. While Lloyd George, who wanted Greece to be brought into the war on the Allied side, if necessary by a naval bombardment, was visiting the Western Front Robertson persuaded the War Committee that Romania was best helped by renewed attacks on the Somme.[117]

Robertson had told Monro, the new Commander-in-Chief India, to "keep up a good show" (1 August 1916) in Mesopotamia but wanted to retreat from Kut to Amara rather than make any further attempt to take Baghdad; this was overruled by Curzon and Chamberlain.[118]

Lloyd George criticised Haig to Foch on a visit to the Western Front in September, and proposed sending Robertson on a mission to persuade Russia to make the maximum possible effort. With Royal backing, and despite Lloyd George offering to go himself, Robertson refused to go, later writing to Haig that it had been an excuse for Lloyd George to "become top dog" and "have his wicked way". Lloyd George continued to demand that aid be sent to help Romania, eventually demanding that 8 British divisions be sent to Salonika. This was logistically impossible, but to Robertson's anger the War Committee instructed him to consult Joffre. Derby dissuaded him from resigning the next day, but instead he wrote a long letter to Lloyd George complaining that Lloyd George was offering strategic advice contrary to his own and seeking the advice of a foreign general, and threatening to resign. That same day Northcliffe stormed into Lloyd George's office to threaten him (he was unavailable) and the Secretary of State also received a warning letter from Gwynne, who had earlier been highly critical of his interview with Foch. Lloyd George had to give his "word of honour" to Asquith that he had complete confidence in Haig and Robertson and thought them irreplaceable. However, he wrote to Robertson wanting to know how their differences had been leaked to the press (although he affected to believe that Robertson had not personally "authorised such a breach of confidence & discipline") and asserting his right to express his opinions about strategy. The Army Council went on record forbidding unauthorised press contacts, although that did nothing to stop War Office leaks.[119]

The Somme ends

At the inter-Allied conference at Boulogne (20 October) Asquith supported Robertson in opposing major offensives at Salonika, although Britain had to agree to send a second British division. Robertson wrote to Repington "If I were not in my present position I daresay I could find half a dozen different ways of rapidly winning this war".[120] He advised Hankey that further high casualties would be needed to defeat Germany's reserves.[108]

The War Committee met (3 November 1916) without Robertson, so Lloyd George could, in Hankey's words "air his views freely unhampered by the presence of that old dragon Robertson". He complained that the Allies had not achieved any definite success, that the Germans had recovered the initiative, had conquered most of Romania, had increased her forces in the East and still had 4 million men in reserve. On this occasion Asquith backed him and the committee's conclusion, which was neither printed nor circulated, was that "The offensive on the Somme, if continued next year, was not likely to lead to decisive results, and that the losses might make too heavy a drain on our resources having regard to the results to be anticipated". It was agreed to consider offensives in other theatres. The ministers again (7 November) discussed, after Robertson had left the room, the plan to send Robertson to a conference in Russia (all except possibly McKenna were in favour) and a further inter-Allied conference to upstage the forthcoming conference of generals at Chantilly. Robertson rejected the idea as "the Kitchener dodge" and was angry at the discussion behind his back and, concerned that Lloyd George wanted to "play hanky panky", refused to go.[121]

Robertson wanted industrial conscription, national service for men up the age of 55, and 900,000 new army recruits, similar to the new German Hindenburg Programme. He was concerned at the Asquith Coalition's lack of firm leadership, once likening the Cabinet to "a committee of lunatics", and although he avoided taking sides in party politics he urged the creation of a small War Committee which would simply give orders to the departmental ministers, and was concerned (letter to Hankey, 9 November) that ministers might be tempted to make peace or else to reduce Britain's Western Front commitment. Robertson gave an abusive response to the Lansdowne Memorandum (13 November 1916) (calling those who wanted to make peace "cranks, cowards and philosophers … miserable members of society").[122]

Robertson successfully lobbied Joffre and at the Chantilly Conference (15–16 November 1916) Joffre and Robertson (in Haig's view) "crushed" Lloyd George's proposal to send greater resources to Salonika.[123]

The Somme ended on 18 November. There was already divergence between MacDonogh and Charteris as to the likelihood of German collapse. Robertson shocked ministers by forecasting that the war would not end until summer 1918.[124] On 21 November, Asquith again met ministers without Robertson present, and they agreed they could not order him to go to Russia. His influence was already beginning to wane.[121] In the event departure, originally scheduled for November, was delayed until January and Wilson was sent in Robertson's place.[125]

At the second Chantilly Conference it had been agreed that Britain would in future take a greater share of the war on the Western Front. Asquith had written to Robertson (21 November 1916) of the War Committee's unanimous approval of the desirability of capturing or rendering inoperable the submarine and destroyer bases at Ostend and Zeebrugge. Haig and Robertson had obtained Joffre's approval for a British Flanders Offensive, after wearing-out attacks by Britain and France.[126]

Lloyd George becomes prime minister

During the December political crisis Robertson advised Lloyd George to form a three-man War Council, which would probably include the Foreign Secretary but not the First Lord of the Admiralty or the Secretary of State for War. He was suspected of briefing the press against Asquith, and had to assure the Palace that this was not so. Robertson warned the first meeting of the new 5-man War Cabinet against the danger of "sideshows". By contrast Hankey advised sending aid to Italy and offensives in Palestine – Lloyd George filed this with the Cabinet papers and used it as the blueprint of future strategy discussions.[127]

With Murray's support, in the autumn of 1916 Robertson had resisted attempts to send as many as 4,000 men to Rabegh to help the nascent Arab Revolt, stressing that logistical support would bring the total up to 16,000 men, enough to prevent Murray's advance on El Arish. Robertson accused the ministers (8 December 1916) of "attaching as much importance to a few scallywags in Arabia as I imagine they did to the German attack on Ypres two years ago", but for the first time ministers contemplated overruling him.[128] Encouraged by hope that the Russians might advance to Mosul, removing any Turkish threat to Mesopotamia, Robertson authorised Maude to attack in December 1916.[129]

Robertson advised against accepting Germany's offer (12 December 1916) of a negotiated peace.[130]

CIGS: Spring 1917

January conferences

Robertson was appointed Aide-de-Camp General to the King on 15 January 1917[131] and was advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath on 24 January 1917.[132]

Following a fractious Anglo-French conference in London (26–28 December) the War Cabinet gave Lloyd George authority to "conclude any arrangement" at the forthcoming Rome conference.[133][134] At the Rome Conference (5–6 January 1917) Lloyd George, advised by Hankey, proposed sending heavy guns to Italy with a view to defeating Austria-Hungary, possibly to be balanced by a transfer of Italian troops to Salonika. Robertson stressed that this was contrary to agreed policy and hinted that he might resign. Cadorna (Hankey suspected he had been "got at by Robertson") stressed the logistical difficulty of accepting the heavy guns, even when Lloyd George removed the precondition that they be returned to the Western Front by May, and even Albert Thomas (French Minister of Munitions) thought it unwise to remove the guns from the Western Front. Robertson wrote to Lloyd George explicitly threatening to resign if he acted on Briand's impassioned plea to send more divisions to Salonika.[133][134]

A further Conference followed in London (15–16 January 1917). Cadorna was also once again talking of being able to win a major victory if reinforced by 300 heavy guns or 8 British divisions – Robertson predictably opposed this (29 January).[135]

Calais

Haig wanted to delay his attack until May to coincide with Italian and Russian attacks, but was told by the government to take over French line as requested, to be ready no later than 1 April, and not cause delays. Robertson was worried about the new French Commander-in-Chief Nivelle forcing the British to attack before the ground dried. Haig demanded a meeting between British and French ministers to resolve matters, although Robertson urged him to resolve them in a face-to-face meeting with Nivelle.[136]

Robertson later claimed that he attended the Calais Conference thinking it would be solely about railways, but this is probably untrue. Robertson was at the War Cabinet (20 February) which insisted on a conference to draw up a formal agreement about "the operations of 1917".[137]

Neither Robertson nor Derby were invited to the War Cabinet on 24 February, at which ministers felt that the French generals and staff had shown themselves to be more skilful than the British, while politically Britain had to give wholehearted support to what would probably be the last major French effort of the war. Hankey also told Stamfordham that on the train to Calais Lloyd George had informed Robertson and Maurice that he had the authority of the War Cabinet "to decide specifically between Generals Haig & Nivelle", although the subordination of Haig to Nivelle had not been specifically discussed.[137]

At Calais (26–7 February), after the railway experts had been sent away, at Lloyd George's request Nivelle produced rules governing the relations between the British and French armies, to be binding also on their successors. Nivelle was to exercise, through British staff at GQG, operational command (including control of logistics and food) of British forces, with Haig left in control only of discipline (which could not legally be placed in foreign hands) and forbidden to make direct contact with London. Haig, Spears later wrote, "had become a cipher, and (his) units were to be dispersed at the will of the French command... until (his) massed thousands had become mere khaki pawns scattered among the sky-blue pawns"[138]

The plans were brought to Robertson, who feeling unwell had dined with Maurice in his room, at around 9pm. In Spears' famous account Robertson's face "went the colour of mahogany ... his eyebrows slanted outwards like a forest of bayonets held at the charge – in fact he showed every sign of having a fit". He shouted "Get 'Aig!". Haig and Robertson visited Lloyd George – one of Robertson's objections was that the agreement could not be binding on Dominion troops – who told them that he had the authority of the War Cabinet and that, although Nivelle's demands were "excessive", they must have a scheme agreed by 8am. The next morning, after Nivelle had claimed he had not personally drawn up the scheme and professed astonishment that the British generals had not already been told of it, Robertson "ramped up and down the room, talking about the horrible idea of putting "the wonderful army" under a Frenchman, swearing he would never serve under one, nor his son either, and that no-one could order him to". Hankey drew up a compromise rather than see Haig and Robertson resign, with Haig still under Nivelle's orders but with tactical control of British forces and right of appeal to the War Cabinet.[139]

Eroding the agreement

Robertson wrote to Haig that Lloyd George was "an awful liar" for claiming that the French had originated the proposal, and that he lacked the "honesty & truth" to remain Prime Minister. Haig claimed that with the BEF spread more thinly by having recently taken over line to the south, German forces might be used to attack at Ypres and cut him off from the Channel Ports. The French assumed Haig was inventing this threat.[140]

Robertson continued to lobby the War Cabinet of the folly of leaving the British Army under French control, passing on Haig's demand that he keep control of the British reserves, and advising that intelligence reports suggested preparations for large-scale German troop movements in Eastern Belgium. With War Cabinet opinion having turned against Lloyd George – who was also rebuked by the King – Robertson also then submitted a memorandum stating that the Calais Agreement was not to be a permanent arrangement, along with a "personal statement" so critical of Lloyd George that he refused to have it included in the minutes.[141]

The King and Esher also urged Haig and Robertson to come to an agreement with the government.[142]

At another conference in London (12–13 March) Lloyd George expressed the government's full support for Haig and stressed that the BEF must not be "mixed up with the French Army", and Haig and Nivelle met with Robertson and Lyautey to settle their differences. The status quo ante, by which British forces were allies rather than subordinates of the French, but Haig was expected to defer to French wishes as far as possible, was essentially restored.[143]

Nivelle Offensive

Robertson came out to Beauvais in March 1917 to demand that Wilson keep him fully informed of all developments.[142] Robertson was sceptical of suggestions that Russia's war effort would be reinvigorated by the Fall of the Tsar, and recommended that Britain keep up the pressure on Germany by attacking on the Western Front. He thought the US, which had declared war on Germany, would do little to help win the war. Robertson prepared another General Staff appraisal stressing how the Allied position had deteriorated since the previous summer, and again recommending diplomatic efforts to detach Germany's allies, although he chose not to circulate it to the civilians.[144] The day after the Nivelle Offensive began, Robertson circulated another paper warning that Nivelle would be sacked if he failed – which is indeed what happened – and urging the end of the Calais Agreement.[145]

Robertson was awarded the French Croix de Guerre on 21 April 1917[146] and appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus from Italy on 26 May 1917.[147]

Other fronts: Spring 1917edit

Lloyd George wanted to make the destruction of Turkey a major British war aim, and two days after taking office told Robertson that he wanted a major victory, preferably the capture of Jerusalem, to impress British public opinion. Robertson thought the capture of Beersheba should suffice, although he told Murray he wanted him to launch a Palestine Offensive, to sustain public morale, in autumn and winter 1917, if the war was still going on then.[148] A January 1917 paper, probably drafted by Macdonogh, argued that, with a compromise peace leaving Germany in control of the Balkans increasingly likely, Britain should protect her Empire by capturing Aleppo, which would make Turkey's hold on Palestine and Mesopotamia untenable.[149]

With Maude having taken Baghdad (11 March 1917), the Turks having withdrawn from Persia and Medina loosely besieged by the Arabs, and Murray having made an apparently successful attack at Gaza (26 March), Robertson asked the War Cabinet for permission to order Murray to renew his offensive. Initial reports turned out to have been exaggerated, and a subsequent attack (17–19 April 1917) also failed. This coincided with the failure of the Nivelle Offensive, reports of unrest among Russian troops after the February Revolution and an escalation of the U-Boat War causing Robertson to prefer a return to a defensive policy in the Middle East.[129]

CIGS: Summer 1917edit

Robertson's views on Flandersedit

As Chief of Staff BEF Robertson had had Maurice, then Director of Military Operations at GHQ, prepare a study of an Ypres Offensive on 15 March 1915. The study had warned that the capture of Ostend and Zeebrugge "would be a very difficult enterprise" and if successful "would not materially improve the military situation" except in the unlikely event that it prompted a general German withdrawal – more likely it would leave the British defending a longer line supplied by only two lines of railway, at "a grave disadvantage" and "in a rather dangerous position" with their backs to the sea as the Germans counterattacked.[150]

By 1917 Robertson was more keen on the idea of the Germans fighting where they would suffer at the hands of strong British artillery. He wrote to Haig (20 April) cautioning against "determination to push on regardless of loss" and repeating Nivelle's error of trying too much to "break the enemy's front" and urged him instead to concentrate on "inflicting heavier losses on (the enemy) than one suffers oneself". It is unclear that the letter had much effect as Haig appointed Gough, an aggressive cavalryman, to command the Ypres Offensive shortly after receiving it.[151]

France steps backedit

With the Nivelle Offensive in its final stages, Lloyd George went to the Paris Summit authorised by the 1 May 1917 War Cabinet to "press the French to continue the offensive". Robertson thought Paris "about the best Conference we have had". With Russian commitment to the war wavering, Smuts, Milner and Curzon agreed with Robertson that Britain must attack in the west lest France or Italy be tempted to make a separate peace.[152]

Petain, committed to only limited attacks, became French Commander-in-Chief (15 May) and with Esher warning that the French government would not honour their Paris commitments, Robertson warned Haig that the British government would not take kindly to high casualties if Britain had to attack without wholehearted French support.[153] Foch, now French chief of staff, also urged Robertson at a meeting (7 June 1917) to conduct only limited attacks until the Americans sent more troops, and they discussed the possibility of attacks on Austria-Hungary designed to encourage her to make peace.[154]

Robertson and Haig met (9 June) after the victory at Messines. Robertson warned Haig that the government were diverting manpower into shipbuilding, ship crews and agriculture rather than the Army, and that a prolonged offensive would leave Britain "without an Army" by the autumn, and suggested that attacks against Austria-Hungary might be more prudent. Haig, dismayed, retorted that "Great Britain must … win the war by herself". Haig also showed Robertson his "Present Situation and Future Plans" (dated 12 June) in which he argued that he had a good chance of clearing the Belgian Coast provided the Germans were unable to transfer reinforcements from the Eastern Front, and that victory at Ypres "might quite possibly lead to (German) collapse". Robertson told Haig he disagreed with the statistical appendix showing German manpower near breaking point and refused to show it to the War Cabinet.[155]

War Policy Committeeedit

The political consensus of May had broken down. Lloyd George told the War Cabinet (8 June) he was dissatisfied with military advice so far and was setting up a War Policy Committee (himself, Curzon, Milner and Smuts).[156] Smuts, newly appointed to the Imperial War Cabinet, recommended renewed western front attacks and a policy of attrition.[157] He privately thought Robertson "good but much too narrow & not adaptable enough".[158]

Robertson objected to proposals to move divisions and heavy guns to Italy. He warned that the Germans could transfer forces to Italy easily, an attack on Trieste might leave Allied forces vulnerable to counterattack from the north, that Cadorna and his army were not competent, and conversely that they might even make peace if they succeeded in capturing Trieste.[156] Robertson complained to Haig of the War Policy Committee's practice of interviewing key people individually to "get at facts" rather than simply setting policy and allowing Robertson and Jellicoe to decide on the military means, and that there would be "trouble" when they interviewed himself and Haig. He wrote that "the (guns) will never go (to Italy) while I am CIGS". He also urged him not to promise, on his forthcoming visit to London, that he could win the war that year but simply to say that his Flanders plan was the best plan, which Robertson agreed it was, so that the politicians would not "dare" overrule both men.[156]

Haig told the War Policy Committee (19 June, and contrary to Robertson's advice) that "Germany was nearer her end than they seemed to think … Germany was within six months of the total exhaustion of her available manpower, if the fighting continues at its present intensity".[159] At this time Haig was involved in discussions as to whether Robertson should be appointed First Lord of the Admiralty (a ministerial post), and Woodward suggests that he may have felt that Robertson had outlived his usefulness as CIGS. Ministers were not entirely convinced by Jellicoe's warnings about German submarines and destroyers operating from the Belgian ports, but were influenced by France's decline and by the apparent success of the Kerensky Offensive. The Flanders Offensive was finally sanctioned by the War Policy Committee on 18 July and the War Cabinet two days later, on condition that it did not degenerate into a long-drawn out fight like the Somme.[160]

To Haig's annoyance the War Cabinet had promised to monitor progress and casualties and, if necessary call a halt. Robertson arrived in France (22 July) to be handed a note from Kiggell, urging that the offensive continue to keep France from dropping out (even if Russia or Italy did). Over dinner Haig urged Robertson to "be firmer and play the man; and, if need be, resign" rather than submit to political interference and on his return Robertson wrote to Haig to assure him that he would always advise "supporting wholeheartedly a plan which has once been approved". Robertson met with Cadorna and Foch (24 July) prior to another inter-Allied conference at Paris, and they agreed that the current simultaneous offensives must take priority over Allied reinforcements for Italy, even though it was now clear that the Kerensky Offensive was failing disastrously and that Germany might sooner or later be able to redeploy divisions to the west.[161]

Middle East: New commanderedit

Curzon (12 May 1917) and Hankey (20 May) continued to urge that Britain seize land in the Middle East. Allenby, Murray's replacement, had been told by Lloyd George that his objective was "Jerusalem before Christmas" and that he had only to ask for reinforcements, but Robertson warned him that he must take into account the needs of other fronts for men and shipping. Allenby's exact remit was still undecided when he was appointed.[162]

Allenby arrived on 27 June 1917. Robertson (31 July) wanted him to keep active so as to prevent the Turks concentrating forces in Mesopotamia, although he scoffed at intelligence reports that the Germans might send as many as 160,000 men to that theatre. Allenby was eventually ordered to attack the Turks in southern Palestine, but the extent of his advance was not yet to be decided, advice which Robertson repeated in "secret and personal" notes (1 and 10 August).[162]

CIGS: Third Ypresedit

Third Ypres beginsedit

Third Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, began on 31 July, with Haig claiming that German losses were double those of the British. Robertson asked Kiggell (2 August) for more information to share with ministers.[161]

After the Inter-Allied conference in London (6–8 August 1917), at which Lloyd George had urged the creation of a common Allied General Staff, Robertson again joined with Foch in claiming that there was not time to send heavy guns to Italy for a September offensive. Robertson wrote to Haig (9 August) that Lloyd George would "put up (the useless) Foch against me as he did Nivelle against you in the Spring. He is a real bad 'un".[163] Haig, at the urging of Whigham (Deputy CIGS), wrote to Robertson (13 August) congratulating him at the way he had "supported the sound policy" in London, but complaining that Macdonogh's "pessimistic estimates" of German losses might cause "many in authority to take a pessimistic outlook" whereas "a contrary view, based on equally good information (sic),[164] would go far to help the nation on to victory".[165]

With the offensive already bogged down in unseasonably early wet weather, Sir John French (14 August 1917) claimed to Riddell (managing director of the News of the World, and likely to pass on French's views to Lloyd George) that Robertson was "anxious to get the whole of the military power into his own hands, that he is a capable organiser but not a great soldier, and we are suffering from a lack of military genius". Lloyd George suggested that all Robertson's plans be submitted to a committee of French, Wilson and one other, although Wilson thought this "ridiculous and unworkable".[166]

Robertson wrote to Haig (17 August) warning him of the shortage of manpower, and to "scrape up all the men (he could) in France". He also warned Haig that there were at that time less than 8,000 "A1" soldiers at home, and that Home Forces were largely made up of "boys" of eighteen whom Robertson, having a son only a few years older, thought too young for service in France. Haig had to tell his Army Commanders that the BEF would be 100,000 men under establishment by October.[165]

The Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo began (18 August) and on 26 August, the British Ambassador in Rome advised that there might be "a complete smashing" of the Austro-Hungarian Army. Robertson advised that it was "false strategy" to call off Third Ypres to send reinforcements to Italy, but after being summoned to George Riddell's home in Sussex, where he was served apple pudding (his favourite dish), agreed to send a message promising support to Cadorna, but only on condition Cadorna promised decisive victory. The Anglo-French leadership agreed in early September to send 100 heavy guns to Italy, 50 of them from the French Army on Haig's left, rather than the 300 which Lloyd George wanted.[167]

Robertson expressed his concern (15 September) that the heavy shelling necessary to break enemy defences at Ypres was destroying the ground.[168]

As soon as the guns reached Italy, Cadorna called off his offensive (21 September).[167]

Third Ypres: reluctance to call a haltedit

Robertson felt that Lloyd George's proposal for an Anglo-French landing at Alexandretta would use up too much shipping and told the War Policy Committee (24 September) that he felt Allenby had enough resources to take Jerusalem, although he stressed the logistical difficulties of advancing 400 miles to Aleppo.[169]

Bonar Law, having guessed from a recent talk with Robertson that he had little hope "of anything coming of" Third Ypres, wrote to Lloyd George that ministers must soon decide whether or not the offensive was to continue. Lloyd George travelled to Boulogne (25 September) where he broached with Painlevé the setting up of an Allied Supreme War Council and then making Foch generalissimo.[170] On 26 September Lloyd George and Robertson met Haig to discuss the recent German peace feelers, one of which suggested she might give up her colonies, Belgium, Serbia and Alsace-Lorraine in return for keeping Poland and the Baltic States. Ministers were reluctant to accept this, but at the same time were concerned that Britain could not defeat Germany singlehandedly (in the event the peace feelers were publicly repudiated by Chancellor Michaelis, and Robertson again urged diplomatic efforts to encourage Bulgaria and Turkey to make peace, although the collapse of Russia made this less likely).[171]

Haig preferred to continue the offensive, encouraged by Plumer's recent successful attacks in dry weather at Menin Road (20 September) and Polygon Wood (26 September), and stating that the Germans were "very worn out". Robertson spoke to the Army Commanders, but declined Haig's offer that he do so without Haig present. He later regretted not having done so, although he was aware of the ill-feeling which Painlevé had caused when he asked Nivelle's subordinates to criticise him.[172] He later wrote in his memoirs that "I was not prepared to carry my doubts to the point of opposing (Haig)" or of preventing one more push which might have "convert(ed) an inconclusive battle into a decisive victory".[171]

On his return Robertson wrote Haig an equivocal letter (27 September) stating that he stuck to his advice to concentrate effort on the Western Front rather than Palestine out of instinct and lack of any alternative than from any convincing argument. He also wrote that "Germany may be much nearer the end of her staying power than available evidence shows" but that given French and Italian weakness it was "not an easy business to see through the problem".[173]

Robertson's refusal to advise a halt to Third Ypres cost him the support of Smuts and Milner. By the end of the year the Cabinet Committee on Manpower were hearing about an alarming rise in drunkenness, desertions and psychological disorders in the BEF, and reports of soldiers' returning from the front grumbling about "the waste of life" at Ypres.[174]

Palestine manpower requirementsedit

At the War Policy Committee (3 October) in Robertson's absence, Lloyd George urged greater effort to advance into Syria with a view to knocking Turkey out of the war; the ministers decided to redeploy two divisions from France. Robertson angered the Prime Minister (5 October) by arguing against this. He also asked Allenby to state his extra troop requirements to advance from the Gaza–Beersheba line (30 miles wide) to the Jaffa–Jerusalem line (50 miles wide), urging him to take no chances in estimating the threat of a German-reinforced threat, but urging Maude not to exaggerate his needs in Mesopotamia.[169]

Robertson, worried that he would be overruled as Painlevé was visiting London for talks, without waiting for Allenby's reply, claimed (9 October) that 5 divisions would need to be redeployed from France to reach the Jaffa-Jerusalem line. That same day Allenby's own estimate arrived, claiming that he would need 13 extra divisions (an impossible demand even if Haig's forces went on the defensive). Yet in private letters Allenby and Robertson agreed that sufficient British Empire troops were already in place to take and hold Jerusalem. The politicians were particularly irritated that they were being shown clearly exaggerated estimates at a time when the General Staff were demanding renewed effort to "divert (Germany's) strategic reserve" to Flanders.[175]

In his 8 October paper, Haig claimed that since 1 April 1917, 135 of the 147 German divisions on the Western Front had been driven from their positions or withdrawn after suffering losses, several of them two or three times, and argued that the Allies could beat Germany in 1918 even if Russia were to make peace. The War Cabinet was sceptical, and in his reply (9 October) Robertson, although he thought Haig's memo "splendid", cautioned that German Army morale still seemed to be holding up well.[176][177] He wrote to Haig in the same letter that "the Palestine thing will not come off", and having heard from Lord Robert Cecil that Haig was dissatisfied with him, asked him to "let me do my own job in my own way" in standing up for proper principles of warfare against Lloyd George. He also commented that (Lloyd George) was "out for my blood very much these days" and claimed that "Milner, Carson, Cecil, Curzon and Balfour, have each in turn expressly spoken to me separately about his intolerable conduct", that he hoped "matters would come to a head" at the next Cabinet as he was "sick of this d–d life", that he would "manage" Lloyd George, and that Painleve's recent visit to London had been an attempt to "carry him off his feet" but that he "had big feet!".[178][179]

Robertson also (9 October) advised against the Prime Minister's recent talk of setting up a Supreme War Council, reminding ministers of the Nivelle fiasco and the sending of heavy guns to Italy only for Cadorna to call off his offensive, and wanted Britain to dominate operations in 1918 by virtue of the strength of her army and her political stability.[180]

Politicians seek other adviceedit

The War Cabinet (11 October 1917) invited Wilson and French to submit formal written advice, a blatant undermining of Robertson's position. Dining with Wilson and French the night before, Lloyd George claimed that Robertson was "afraid of Haig, & that both of them are pigheaded, stupid & narrow visioned".[181] Wilson and French urged no major war-winning offensive until 1919. Robertson thought the War Cabinet a "weak kneed craven hearted Cabinet ... Lloyd George hypnotises them and is allowed to run riot". Derby had to remind them that Robertson was still their constitutional adviser, and Haig was too busy to come to a planned showdown to which Lloyd George invited him and Robertson.[182] Haig advised Robertson not to resign until his advice had actually been rejected.[177]

As advised by Wilson and Viscount French, Lloyd George persuaded the War Cabinet and the French to agree to a Supreme War Council. Hankey (20 October) suspected that the plan of an inter-allied staff of generals in Paris would alone be enough to drive Robertson to resignation. Wilson was appointed British Permanent Military Representative after it had been offered to Robertson (which would have meant giving up his CIGS job). Robertson later claimed in his memoirs that he supported the SWC as a political body, but not the military advisers providing separate advice from the national general staffs.[182][183][184]

CIGS: 1917–18edit

Rapallo and Parisedit

The argument was overtaken by disaster on the Italian front: the Battle of Caporetto began on 24 October. Robertson later wrote to Edmonds in 1932 that although he had kept the diversion of divisions to Italy to a minimum, some reinforcements had to be sent.[185] Robertson went to Italy to supervise deployment of British divisions, meeting Lloyd George, Hankey and Wilson when they arrived for the Rapallo Conference (6–7 November), which formally established the Supreme War Council. Robertson had been told by Hankey that Lloyd George had the War Cabinet's backing, and Lloyd George later wrote of Robertson's "general sulkiness" and "sullen and unhelpful" attitude at the conference. He walked out of the meeting, telling Hankey "I wash my hands of this business", and contemplated resignation, as he had over the French-Wilson papers.[184][186]

Lloyd George and Robertson had long been briefing the press against one another. After Lloyd George's Paris speech (12 November), in which he said that "when he saw the appalling casualty lists" he "wish(ed) it had not been necessary to win so many ("victories")", and unlike the Nivelle Affair, Lloyd George's differences with the generals were being aired in public for the first time. The Daily News, Star and Globe attacked Lloyd George.[187][188]

Robertson reported to the War Cabinet (14 November) that Italy's situation was like that of Russia in 1915 and that she might not recover. In his paper "Future Military Policy" (19 November), Robertson was impressed by the French Army's recovery under Petain but advised that lack of French reserves might make major French offensives in 1918 unlikely. He rejected a purely defensive posture in the west, as even defending would still result in heavy casualties, but was sceptical of Haig's wish to renew the Ypres Offensive in Spring 1918, and argued that Britain should build up her strength on the Western Front and then decide on the scale of her 1918 offensives. He warned (correctly) that, with Russia dropping out of the war, the Germans would use the opportunity to attack in 1918 before the American Expeditionary Force were present in strength. Lloyd George replied (wrongly) that the Germans would not attack and would fail if they did.[189]

Amid talk of Austen Chamberlain withdrawing support from the government, Robertson briefed the Opposition Leader Asquith. However, Lloyd George survived the Commons debate on Rapallo (19 November) by praising the generals and claiming that the aim of the Supreme War Council was purely to "coordinate" policy.[187][188]

SWC and Inter-Allied Reserveedit

Derby got the Prime Minister to agree that Robertson should accompany Wilson (British Military Representative) to all Supreme War Council meetings and he would make no proposals until Robertson and the War Council had had a chance to vet them. He then reneged on this promise, telling Derby (26 November) that Robertson would have a chance to comment at the meeting itself and that decisions would have to ratified by the War Cabinet after they had been made. Lloyd George restored Wilson's freedom of action by instructing Wilson to send his reports directly to him.[188][190]

Hankey wrote (26 November) that only Britain, the US and Germany were likely to last until 1919 and that "on the whole the balance of advantage lies with us, provided we do not exhaust ourselves prematurely".[191]

By the time of the initial SWC meeting (Versailles 1 December 1917) Allenby's successes, culminating in the Fall of Jerusalem (9 December 1917), demonstrated the potential of attacks in the Middle East, particularly compared to Haig's apparently unproductive offensive at Ypres, followed by Cambrai in November (initial success followed by retaking of gains). Russia had finally collapsed (Brest Litovsk Armistice 16 December) yet only a handful of American divisions were available so far in the west.[190]

After the Fall of Jerusalem Derby threatened to resign if Lloyd George sacked Robertson, but the War Cabinet (11–12 December) minuted its dissatisfaction at the information which he had given them about Palestine. Maurice claimed that intelligence from Syria "was too stale to be of use" and Robertson claimed that the speed of Allenby's advance, often with little water, had taken everyone by surprise.[192]

After the Fall of Jerusalem, Allenby irritated Robertson by writing that he could conquer the rest of Palestine with his present force of 6–8 divisions, but said he would need 16–18 divisions for a further advance of 250 miles to Aleppo (the Damascus-Beirut Line) to cut Turkish communications to Mesopotamia. In a paper of 26 December, Robertson claimed that the conquest of the remainder of Palestine might mean an extra 57,000 battle casualties and 20,000 sick. Amery (30 December) thought this "an amazing document even from him" and that such arguments could have been produced against any major campaign in history. By mid-January Amery and Lloyd George were arranging for the Permanent Military Representatives at Versailles to discuss Palestine (they thought Turkish ration strength was 250,000 "at most" whereas the General Staff put it at 425,000, of whom around half were combatants).[193]

Robertson tried to control Lt Gen Sir William Raine Marshall (Maude's replacement as C-in-C Mesopotamia) by handpicking his staff. Smuts was sent to Egypt to confer with Allenby and Marshall and prepare for major efforts in that theatre. Before his departure, alienated by Robertson's cooking of the figures, he urged Robertson's removal. Allenby told Smuts of Robertson's private instructions (sent by hand of Walter Kirke, appointed by Robertson as Smuts' adviser) that there was no merit in any further advance and worked with Smuts to draw up plans for further advances in Palestine.[194]

Wilson wanted Robertson reduced "from the position of a Master to that of a servant". Robertson thought Wilson's SWC Joint Note 12, which predicted that neither side could win a decisive victory on the Western Front in 1918, and that decisive results could be had against Turkey, "d-----d rot in general" and promised Haig he would "stick to (his) guns and clear out if (he was) overruled". Robertson opposed attacks on Turkey, siding openly with Clemenceau against Lloyd George. Although Robertson apologised for doing so, the Prime Minister was angry and told Wilson afterwards that he would have to get rid of Robertson. Robertson's request to be on the Executive Board controlling the planned Allied General Reserve was overruled.[195][196]

Robertson called the Executive War Board the "Versailles Soviet" and claimed to the King's adviser Lord Stamfordham that having "practically, two CIGSs" would lead to "destruction of confidence among the troops". He also briefed Gwynne against the proposals, writing that "the little man" was "all out for (his) blood" and "to see that the fine British Army is not placed at the mercy of irresponsible people – & some of them foreigners at that".[197]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=William_Robertson_(British_Army_officer)Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk