A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

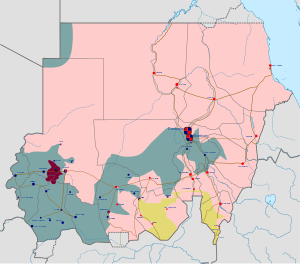

A civil war between two rival factions of the military government of Sudan, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) under Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) under the Janjaweed leader, Hemedti, began during Ramadan on 15 April 2023. Fighting has been concentrated around the capital city of Khartoum and the Darfur region.[40] As of 21 January 2024, at least 13,000[41]–15,000 people had been killed and 33,000 others were injured.[38] As of 21 March, over 6.5 million were internally displaced and more than two million others had fled the country as refugees,[39] and many civilians in Darfur have been reported dead as part of the 2023 Masalit massacres.[42]

The war began with attacks by the RSF on government sites as airstrikes, artillery, and gunfire were reported across Sudan. The cities of Khartoum and Omdurman were divided between the two warring factions, with al-Burhan relocating his government to Port Sudan as RSF forces captured most of Khartoum's government buildings. Attempts by international powers to negotiate a ceasefire culminated in the Treaty of Jeddah, which failed to stop the fighting and was ultimately abandoned.[43]

Over the next few months, a stalemate occurred, during which the two sides were then joined by rebel groups who had previously fought against Sudan's government. By mid-November, the Minni Minnawi and Mustafa Tambour factions of the Sudan Liberation Movement officially joined the war in support of the SAF, alongside the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM).[3][44] In contrast, the Tamazuj movement joined forces with the RSF, while the Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement–North attacked SAF positions in the south of the country.[25][45][46]

Starting in October 2023, momentum began to swing toward the RSF, as the paramilitary defeated army forces in Darfur and made gains in Khartoum State, Kordofan, and Gezira State. Since February 2024, the SAF has made gains in Omdurman as part of the 2024 Omdurman offensive. Further negotiations between the warring sides have so far produced no significant results, while many countries have provided military or political support for either al-Burhan or Hemedti.[47][48]

Background

The history of conflicts in Sudan has consisted of foreign invasions and resistance, ethnic tensions, religious disputes, and disputes over resources.[49][50] Since independence in 1956, Sudan has experienced more than 15 military coups[51] and usually been ruled by the military, interspersed with short periods of democratic parliamentary rule.[52][53]

Two civil wars between the central government and the southern regions, which led to the independence of South Sudan in 2011, killed 1.5 million people, and a conflict in the western region of Darfur displaced two million people and killed more than 200,000 others.[54]

War in Darfur and the formation of the RSF

By the turn of the 21st century, Sudan's western Darfur region had endured prolonged instability and social strife due to a combination of racial and ethnic tensions and disputes over land and water. In 2003, this situation erupted into a full-scale rebellion against government rule, against which president and military strongman Omar al-Bashir vowed to use forceful action. The resulting War in Darfur was marked by widespread state-sponsored acts of violence, leading to charges of war crimes and genocide against al-Bashir.[55] The initial phase of the conflict left approximately 300,000 dead and 2.7 million were forcibly displaced; even though the intensity of the violence later declined, the situation in the region remained far from peaceful.[56]

To crush uprisings by non-Arab tribes in the Nuba Mountains, al-Bashir relied upon the Janjaweed, a collection of Arab militias which was drawn from camel-trading tribes which were active in Darfur and portions of Chad. In 2013, al-Bashir announced that the Janjaweed would be reorganized as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and he also announced that the RSF would be placed under the command of the Janjaweed's commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, more commonly known as Hemedti.[57][58][59][60] The RSF perpetrated mass killings, mass rapes, pillage, torture, and destruction of villages and were accused of committing ethnic cleansing against the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa peoples.[59] Leaders of the RSF have been indicted for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court (ICC),[61] but Hemedti was not personally implicated in the 2003–2004 atrocities.[56] In 2017, a new law gave the RSF the status of an "independent security force".[59] Hemedti received several gold mines in Darfur as patronage from al-Bashir, and his personal wealth grew substantially.[60][61] Bashir sent RSF forces to quash a 2013 uprising in South Darfur and deployed RSF units to fight in Yemen and Libya.[58] During this time, the RSF developed a working relationship with the Russian private military outfit Wagner Group.[62] These developments ensured that RSF forces grew into the tens of thousands and came to possess thousands of armed pickup trucks which regularly patrolled the streets of Khartoum.[62] The Bashir regime allowed the RSF and other armed groups to proliferate to prevent threats to its security from within the armed forces, a practice known as "coup-proofing".[63]

Political transition

In December 2018, protests against al-Bashir's regime began, starting the first phase of the Sudanese Revolution. Eight months of sustained civil disobedience were met with violent repression.[64] In April 2019, the military (including the RSF) ousted al-Bashir in a coup d'état, ending his three decades of rule; the army established the Transitional Military Council, a junta.[60][61][64] Bashir was imprisoned in Khartoum; he was not turned over to the ICC, which had issued warrants for his arrest on charges of war crimes.[65] Protests calling for civilian rule continued; in June 2019, the TMC's security forces, which included both the RSF and the SAF, perpetrated the Khartoum massacre, in which more than a hundred demonstrators were killed[66][58][60][64] and dozens were raped.[58] Hemedti denied orchestrating the attack.[60]

In August 2019, in response to international pressure and mediation by the African Union and Ethiopia, the military agreed to share power in an interim joint civilian-military unity government (the Transitional Sovereignty Council), headed by a civilian Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, with elections to be held in 2023.[55][64] In October 2021, the military seized power in a coup led by Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Hemedti. The Transitional Sovereignty Council was reconstituted as a new military junta led by al-Burhan, monopolizing power and halting Sudan's transition to democracy.[65][67]

Origins of the SPLM-N and the SLM

The Sudan Liberation Movement (or Army; SLM, SLA, or SLM/A) is a rebel group active in Darfur, primarily composed of members of non-Arab ethnic groups[68] and established in response to their marginalization by the Bashir regime.[69][70] Since 2006, the movement has split into several factions due to disagreements over the Darfur Peace Agreement, with some factions joining the government in Khartoum.[71][72][73] By 2023 the three most prominent factions were the SLM-Minnawi under Minni Minnawi, the SLM-al-Nur under Abdul Wahid al-Nur, and the SLM-Tambour under Mustafa Tambour. The SLM-Minnawi and SLM-Tambour signed the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement, ceasing hostilities and receiving political appointments, but the SLM-al-Nur had refused to sign and kept fighting.[74][75]

The SPLM-N was founded by units of the predominantly South Sudanese Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army stationed in areas that remained in Sudan following the South Sudanese vote for independence in 2011. These forces then led a rebellion in the southern states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile a few months later.[76] In 2017, the SPLM-N split between a faction led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu and one led by Malik Agar, with al-Hilu demanding secularism as a condition for peace while Agar did not agree with this.[77] During the Sudanese Revolution, al-Hilu's faction declared an indefinite unilateral ceasefire.[78] In 2020, a peace agreement was signed between the Sudanese government and Agar's faction,[79] with Agar later joining the Transitional Sovereignty Council in Khartoum. Al-Hilu held out until he agreed to sign a separate peace agreement with the Sudanese government a few months after.[80] Further steps to consolidate the agreement stalled following the 2021 coup, and the al-Hilu faction instead signed an agreement with the SLM-al-Nur and the Sudanese Communist Party, agreeing to co-operate in order to draft a 'revolutionary charter' and remove the military from power.[81]

Prelude

In the months after the 2021 coup the already weak Sudanese economy steeply declined, fueling wide protests demanding that the junta relinquish power back to civilian authorities.[82] Tensions arose between the two junta leaders over al-Burhan's restoration to office of old-guard Islamist officials who had dominated the Omar al-Bashir government. Hemedti saw the appointment of these officials as a signal that al-Burhan was attempting to maintain the dominance of Khartoum's traditional elite over Sudanese politics. This was a danger to the RSF's political position, as said elites were hostile to Hemedti due to his ethnic background as a Darfuri Arab.[83] Hemedti's expression of regret over the October 2021 coup signals a widening divide between him and al-Burhan.[67]

Tensions between the RSF and the SAF began to escalate in February 2023, as the RSF began to recruit members across Sudan.[82] Throughout February and early March the military built up in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum, until a deal was brokered on 11 March and the RSF withdrew.[82][84] As part of this deal negotiations were conducted between the SAF, RSF, and civilian leaders, yet these were delayed and halted by political disagreements.[85] Chief among the disputes was the integration of the RSF into the military: the RSF insisted on a 10-year timetable for its integration into the regular army, while the army demanded integration within two years.[86][87] Other contested issues included the status given to RSF officers in the future hierarchy, and whether RSF forces should be under the command of the army chief rather than Sudan's commander-in-chief, al-Burhan.[88]

On 11 April 2023, RSF forces were deployed near the city of Merowe as well as in Khartoum.[89] Government forces ordered them to leave, and were refused. This led to clashes when RSF forces took control of the Soba military base south of Khartoum.[89] On 13 April, RSF forces began their mobilization, raising fears of a potential rebellion against the junta. The SAF declared the mobilization illegal.[90]

Course

April–May 2023

Battle of Khartoum

On 15 April 2023, the RSF attacked SAF bases across Sudan, including Khartoum and its airport.[86][91] There were clashes at the headquarters of the state broadcaster, Sudan TV, which was later captured by RSF forces.[92] Bridges and roads in Khartoum were closed, and the RSF claimed that all roads heading south of Khartoum were closed.[93] The next day saw a SAF counteroffensive, with the army retaking Merowe Airport alongside the headquarters of Sudan TV and the state radio.[94][95]

The Sudan Civil Aviation Authority closed the country's airspace as fighting began.[96] Telecommunications provider MTN shut down Internet services, and by 23 April there was a near-total Internet outage across Sudan. This was attributed to electricity shortages caused by attacks on the electric grid.[97][98] Sudanese international trade began to break down, with Maersk, one of the largest shipping companies in the world, announcing a pause on new shipments to the country.[99]

Hemedti directed his forces to capture or kill al-Burhan, and RSF units engaged in pitched and bloody combat with the Republican Guard. Ultimately al-Burhan managed to evade capture or assassination, but his base at the Sudanese Armed Forces Headquarters was eventually placed under RSF siege, rendering him unable to leave Khartoum.[74][100] In an interview with Al Jazeera, Hemedti accused al-Burhan and his commanders of forcing the RSF to start the war by scheming to bring deposed leader Omar al-Bashir back to power.[101] He called for the international community to intervene against al-Burhan, claiming that the RSF was fighting against radical Islamic militants.[102]

Following the first few days of war the SAF brought in reinforcements from the Ethiopian border.[103] Although a ceasefire was announced for Eid al-Fitr, fighting continued across the country.[104][105] Combat was described as particularly intense along the highway from Khartoum to Port Sudan and in the industrial zone of al-Bagair.[106] Intercommunal clashes were reported in Blue Nile State and in Geneina.[107][108]

By the beginning of May the SAF claimed to have weakened the RSF's combat capabilities and repelled their advances in multiple regions.[109] The Sudanese police deployed its Central Reserve Forces in the streets of Khartoum in support of the SAF, claiming to have arrested several hundred RSF fighters.[110] The SAF announced it was launching an all-out attack on RSF in Khartoum using air strikes and artillery.[111] Air strikes and ground offensives against the RSF over the next few days caused significant damage to infrastructure, but failed to dislodge RSF forces from their positions.[112][113]

Following further threats to his life from Hemedti, al-Burhan gave a public video address from his besieged base at the Army Headquarters, vowing to continue fighting.[114][115] On 19 May, al-Burhan officially removed Hemedti as his deputy in the Transitional Sovereignty Council and replaced him with former rebel leader and council member Malik Agar.[116] With al-Burhan trapped in Khartoum, Agar became de facto leader of the Sudanese government, assuming responsibility for peace negotiations, international visits and the day-to-day running of the country.[74]

Treaty of Jeddah

International attention to the conflict resulted in the United Nations Human Rights Council calling a special session to address the violence, voting to increase monitoring of human rights abuses.[117] On 6 May, delegates from the SAF and the RSF met directly for the first time in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for what was described by Saudi Arabia and the United States as "pre-negotiation talks".[118] After diplomatic lobbying from the Saudis and Americans the warring sides signed the Treaty of Jeddah on 20 May, vowing to ensure the safe passage of civilians, protect relief workers, and prohibit the use of civilians as human shields.[119] The agreement did not include a ceasefire, and clashes resumed in Geneina, causing more casualties.[119] The United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Martin Griffiths expressed frustration at the lack of commitment from both sides to end the fighting.[120]

The situation remained volatile, with both sides trading blame for attacks on churches,[121] hospitals,[122] and embassies.[123] Casualties mounted, particularly in Geneina, where Arab militias loyal to the RSF were accused of atrocities against non-Arab residents.[124] A temporary ceasefire was signed and faced challenges as fighting persisted in Khartoum, and the agreed-upon ceasefire time saw further violence.[125] Between 28 and 97 people were reportedly killed by the RSF and Arab militias when they attacked the predominantly Masalit town of Misterei in West Darfur on 28 May.[126]

June–September 2023

Continued fighting in Khartoum

As June began, Khartoum witnessed tank battles resulting in casualties and injuries.[127][128] The RSF took control of several important cultural and government buildings, including the National Museum of Sudan and the Yarmouk Military Industrial Complex.[129][130] Acute food insecurity affected a significant portion of Sudan's population.[131]

By July, al-Burhan was still trapped at the Army Headquarters and unable to leave, and in order to break him out the SAF elected to send a column of troops to lift the siege of the base. This force was ambushed by the RSF and defeated, with the paramilitary claiming it had killed hundreds of soldiers and captured 90 vehicles, along with the column's commander.[132]

In response to the escalating violence in Khartoum the SAF increased the intensity of their airstrikes and artillery bombardment, leading to heightened civilian casualties often numbering in the dozens per strike.[133][134][135] Shelling by the RSF also increased in intensity, leading to many civilian casualties in turn.[136][137]

Heavy fighting continued in Khartoum throughout August, with clashes breaking out across the city. The RSF laid siege to the SAF's Armoured Corps base, breaching its defences and taking control of surrounding neighbourhoods.[138][139] The SAF also made offensives, with the RSF-controlled Republican Palace and Yarmouk Complex coming under SAF air bombardment. An offensive was launched against Yarmouk, but this was beaten back after the RSF shipped in reinforcements.[140] One of the few remaining bridges between Khartoum and Khartoum North was also destroyed by the SAF, in an attempt to deny the RSF freedom of movement.[141]

On 24 August a SAF military operation successfully rescued al-Burhan from his besieged base at the Army Headquarters, allowing him to head to Port Sudan and hold a cabinet meeting there.[142][143]

Diplomatic efforts

Ceasefires between the warring parties were announced but often violated, leading to further clashes. The SAF and RSF engaged in mutual blame for incidents, while the Sudanese government took actions against international envoys.[144] The Saudi embassy in Khartoum was attacked, and evacuations from an orphanage were carried out amid the chaos.[145] Amidst the turmoil, Sudan faced diplomatic strains with Egypt, leading to challenges for Sudanese refugees seeking entry.[146][147]

With al-Burhan out of Khartoum for the first time since the start of the war, he was able to fly to Egypt and hold a meeting with the Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.[148] Following this visit al-Burhan went on a tour of numerous countries, heading to South Sudan, Qatar, Eritrea, Turkey, and Uganda.[149] He then proceeded to New York City as head of the Sudanese delegation to the 78th United Nations General Assembly, where he urged the international community to declare the RSF a terrorist organization.[150][151]

SPLM-N (Al-Hilu) involvement

The Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N) broke a long-standing ceasefire agreement in June, attacking SAF units in Kadugli, Kurmuk and Dalang, the latter coinciding with an attack by the RSF. The SAF claimed to have repelled the attacks,[45][152] while the rebels claimed to have attacked in retaliation for the death of one of their soldiers at the hands of the SAF and vowed to free the region from "military occupation".[78] More than 35,000 were displaced by the fighting.[78] Speculation arose as to whether the attacks were part of an unofficial alliance between al-Hilu and the RSF or an attempt by al-Hilu to strengthen his position in future negotiations concerning his group.[153] Civil society organizations supporting the SPLM-N claimed its operations sought to protect civilians from possible attacks by the RSF.[154]

Al-Hilu's faction launched further offensives in July, moving into South Kordofan and gaining control of several SAF bases.[155][156] In response the SAF brought in artillery and heavily bombarded SPLM-N positions.[155] Further attacks by the group largely petered out after this, with an assault on Kadugli in September being pushed back by the SAF.[157]

Darfur front

In Darfur fighting and bloodshed was particularly fierce around the city of Geneina, where hundreds died and extensive destruction occurred.[158] RSF forces engaged in frequent acts of violence against the Masalit population of Geneina, leading to accusations of ethnic cleansing.[159] On 4 August the RSF claimed that it had taken full control over all of Central Darfur.[160]

A United Nations investigation discovered numerous mass graves in Darfur that contained Masalit civilians.[161] The RSF and Arab militias were additionally accused of having killed lawyers, human rights monitors, doctors and non-Arab tribal leaders.[162] The governor of West Darfur, Khamis Abakar, was abducted and killed by armed men in June, hours after accusing the RSF of genocide and calling for international intervention in a TV interview.[163] The SAF, for their part, conducted indiscriminate airstrikes against Darfur that killed many civilians, especially in Nyala.[164]

Tribal and rebel groups in Darfur began to declare allegiance to one or the other of the warring parties. A faction of the Darfur-based Sudan Liberation Movement led by Mustafa Tambour (SLM-T) joined the conflict in support of the SAF.[3] In contrast the controversial Tamazuj rebel group formally declared its alliance with the RSF, joined by the leaders of seven Arab tribes, including that of Hemedti's.[46][165]

As September arrived both sides made offensives in Darfur. The RSF took control of several towns in West Darfur and also attacked the market of Al-Fashir, the capital of North Darfur.[166] SAF offensives saw success in Central Darfur, with the army retaking parts of Zalingei from the RSF.[167] Fighting in Darfur also began to increasingly spill over into North Kordofan, with the SAF attacking RSF positions in the state capital of El-Obeid and clashes over the town of Um Rawaba.[168] Both sides made withdrawals to end the month, with the RSF retreating from Um Rawaba while the SAF withdrew from Tawila.[169][170]

October–December 2023

SAF collapse in Darfur

By October, the SAF in Darfur was experiencing acute shortages in supplies due to RSF-imposed sieges, and had failed to utilize its air superiority to stem RSF advances.[171] On 26 October, the RSF captured Nyala, Sudan's fourth-largest city, after seizing control of the SAF's 16th Infantry Division headquarters.[172] The fall of Nyala, a strategic city with an international airport and border connections to Central Africa, allowed the RSF to receive international supplies more easily and concentrate its forces on other Sudanese cities.[173] After Nyala's fall, RSF fighters turned their focus to Zalingei, the capital of Central Darfur. The SAF's 21st Infantry Division, stationed in Zalingei, fled the city without a fight and allowed the RSF to take it over.[174]

In Geneina, reports emerged that tribal elders were attempting to broker the surrender of the SAF garrison in the city to prevent bloodshed.[175] The army rejected the proposal, raising fears of an imminent RSF assault on the city and causing civilians to flee across the border into Chad.[176] The RSF besieged the headquarters of the SAF's 15th Infantry Division in Geneina, giving the garrison a six-hour ultimatum to surrender.[177] The base was captured two days later when the 15th withdrew from the area before fleeing to Chad in haste.[178] Those left behind, numbering in the hundreds, were taken prisoner and paraded in RSF media with signs of abuse.[178] Witnesses later reported of mass atrocities perpetrated by the RSF in the city shortly after its seizure, with a local rebel group claiming up to 2,000 people were massacred in Geneina's satellite town of Ardamata.[179] With Geneina's fall, Ed Daein and Al-Fashir were the last remaining capitals in Darfur under government control, with both cities under heavy RSF pressure.[175][178]

The RSF stormed and plundered the town of Umm Keddada, east of Al-Fashir, after the SAF garrison withdrew.[179] SAF troops in Al-Fashir itself were reported to be running low on food, water, and medicine due to the city being under siege, and external forces noted the SAF seemed incapable of stopping the RSF advance.[180][181] Ed Daein fell in the early hours of 21 November, with RSF forces taking control of the city after seizing the headquarters of the SAF's 20th Infantry Division.[182] SAF garrisons in East Darfur subsequently abandoned their positions and withdrew, allowing the RSF to occupy the area.[183] In response to RSF gains in Darfur and subsequent abuses, the Justice and Equality Movement, Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (Minnawi), and other smaller rebel factions renounced their neutrality and declared war on the RSF.[184]

Peace negotiations stall

Attempts by other nations and international organisations to negotiate peace had largely been dormant since the failure of the Treaty of Jeddah, but in late October the RSF and SAF met once more in Jeddah to attempt to negotiate peace.[185] This new round of talks was a failure, with neither side willing to commit to a ceasefire. Instead, the warring factions agreed to open channels for humanitarian aid.[186] On 3 December negotiations were indefinitely suspended due to the failure of both the SAF and the RSF to open up aid channels.[187]

With the failure of the talks in Jeddah, the East African Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) hosted a peace summit in early December. Earlier attempts by IGAD to open negotiations had floundered after the SAF had accused Kenyan President William Ruto of supporting the RSF.[188] IGAD's talks appeared to make more progress than the Jeddah negotiations, with Hemedti and al-Burhan agreeing to meet in person at some point in the future.[189]

RSF Crossing of the Nile

The RSF attacked the town of Wad Ashana in North Kordofan on 1 October along a key commercial route.[190][191] In West Kordofan, an uptick in fighting was reported, with the RSF assaulting a "vital" oil field in Baleela, south of Al-Fulah.[192] Geolocated footage showed RSF fighters celebrating around Baleela Airport after allegedly capturing it.[193] The Battle of Khartoum continued with the RSF seizing the town of al-Aylafoun, southeast of the capital, on 6 October. In the process, the paramilitary gained control of key oil infrastructure.[194][195] By late October the RSF controlled most of Khartoum but had failed to seize key military bases, while al-Burhan's government had largely relocated to Port Sudan.[196]

The RSF sought to capitalize on its gains by stepping up attacks on SAF positions in Khartoum and Omdurman. Days of fighting culminated in the destruction of the Shambat Bridge, which connected Khartoum North to Omdurman over the Nile; the bridge's destruction severing a critical RSF supply chain.[197] This effectively cut the RSF off from its forces in Omdurman, giving the SAF a strategic advantage.[198] In an attempt to gain a new crossing over the Nile and supply its forces in Omdurman, the RSF launched an assault on the Jebel Aulia Dam in the village of Jabal Awliya.[199] As Jebel Aulia could not be destroyed without flooding Khartoum, its capture would give the RSF a path over the Nile the SAF could not easily remove. A week-long battle commenced over the dam and its surrounding village, which ended in an RSF victory. The force captured the dam on 20 November, all SAF resistance ceasing in the village the following day.[200][201]

On 5 December, local militias along with RSF soldiers attacked SPLM-N (al-Hilu) forces in the village of Tukma, southeast of Dalang in South Kordofan, resulting in the deaths of 4 people and the destruction of the village.[26] The RSF leadership, not wanting hostilities with the neutral al-Hilu faction to escalate, issued a statement condemning this attack and denouncing it as "tribal violence".[202] On 8 December, the RSF entered Gedaref State for the first time.[202]

Pushing south from their gains around Jebel Aulia and Khartoum, RSF forces began to move into Gezira State on 15 December, advancing toward its capital Wad Madani.[203][204] Elsewhere in Gezira the RSF made major gains, taking control of the city of Rufaa in the state's east and entering the Butana region.[205] After several days of fighting the RSF seized the Hantoob Bridge on Wad Madani's eastern outskirts, crossing the Blue Nile and entering the city.[205] The army put up little resistance in Wad Madani itself, the 1st Division withdrawing from the city as the RSF took over.[206]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=War_in_Sudan_(2023)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

1443

1895

1903

1918

1966

2016

2023 Argentine general election

2023 Cricket World Cup

2023 Cricket World Cup final

2023 Israel–Hamas war

2023 MotoGP World Championship

30. roky 12. storočia

Akazehe

Angeline Quinto

Annabel Giles

Art Deco architecture of New York City

Associação Chapecoense de Futebol

Australia national cricket team

Auto racing

Bukovina Day

Canadian football

Cartography

Chicago Times-Herald race

Deaths in 2023

East Germany

Eddie Linden

Encyclopedia

English language

Erin Swenson

Ernani

Euromir

European Space Agency

Felis wenzensis

File:Francesco 'Pecco' Bagnaia at the 2023 Japanese motorcycle Grand Prix (cropped).jpg

File:Gjergj Kastrioti.jpg

File:Hyles gallii - Keila1.jpg

File:Luca Salsi.jpg

File:Ulf D. Merbold.jpg

Francesco Bagnaia

Free content

Garry Moore

Gender transition

Geordie Walker

Harald Hasselbach

Helen of Greece and Denmark

Help:Introduction to Wikipedia

Help:Your first article

Hyles gallii

India national cricket team

Javier Milei

Keila

Kingdom of Burundi

Krujë

LaMia Flight 2933

Leo Bagrow

List of days of the year

List of Wikipedias

Luca Salsi

Lucia di Lammermoor

Magnus Olsen

Manuel I Komnenos

Margarita Ortega (magonist)

Medellín

Metropolitan Opera

Mexican Revolution

Michel Micombero

Micronations and the Search for Sovereignty

Mir

Montreal Alouettes

Moth

Motorcycle racing

Murad II

Myanmar civil war (2021–present)

My Personal Weatherman

NASA

November 27

November 28

November 29

Oil spill

Ottoman Empire

Payload specialist

Picklesburgh

Point Nepean

Portal:Current events

President of Argentina

Russian invasion of Ukraine

S. A. von Rottemburg

S. Venkitaramanan

Skanderbeg

Space Shuttle Columbia

Species description

Sphingidae

SS Petriana

Statelessness

STS-42

STS-9

Template:POTD/2023-11-25

Template:POTD/2023-11-26

Template:POTD/2023-11-27

Template talk:Did you know

Terry Venables

Timeline of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (1 September 2023 – present)

Ulf Merbold

University of Stuttgart

User:Iifar

War in Sudan (2023)

West Germany

White Australia policy

Wikimedia Foundation

Wikipedia

Wikipedia:About Today's featured article

Wikipedia:Community portal

Wikipedia:Contents/Portals

Wikipedia:Featured articles

Wikipedia:Featured pictures

Wikipedia:Help desk

Wikipedia:In the news/Candidates

Wikipedia:News

Wikipedia:Picture of the day/Archive

Wikipedia:Recent additions

Wikipedia:Reference desk

Wikipedia:Selected anniversaries/November

Wikipedia:Teahouse

Wikipedia:Today's featured article/November 2023

Wikipedia:Village pump

Winnipeg Blue Bombers

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk