A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| 1953–1964 | |||

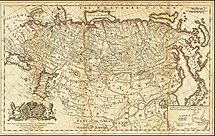

The USSR: the maximum extent of the Soviet sphere of influence, after the Cuban Revolution (1959) and before the Sino-Soviet split (1961). | |||

| Location | Soviet Union | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Including | Cold War | ||

| Leader(s) | Georgy Malenkov Nikita Khrushchev | ||

| Key events | East German uprising of 1953 Vietnam War Suez Crisis Space Race On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences De-Stalinization Hungarian Revolution of 1956 Virgin Lands campaign Cuban Revolution 1959 Tibetan uprising Sino–Soviet split Novocherkassk massacre Cuban Missile Crisis 1963 Moscow protest | ||

Chronology

| |||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

In the USSR, during the eleven-year period from the death of Joseph Stalin (1953) to the political ouster of Nikita Khrushchev (1964), the national politics were dominated by the Cold War, including the U.S.–USSR struggle for the global spread of their respective socio-economic systems and ideology, and the defense of hegemonic spheres of influence. Since the mid-1950s, despite the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) having disowned Stalinism, the political culture of Stalinism — a very powerful General Secretary of the CPSU—remained in place, albeit weakened.

Politics

Stalin's immediate legacy

After Stalin died in March 1953, he was succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and Georgy Malenkov as Premier of the Soviet Union. However the central figure in the immediate post-Stalin period was the former head of the state security apparatus, Lavrentiy Beria.

Stalin had left the Soviet Union in an unenviable state when he died. At least 2.5 million people languished in prison and in labor camps, science and the arts had been subjugated to socialist realism, and agriculture productivity on the whole was meager. The country had only one quarter of the livestock it had had in 1928 and in some areas, there were fewer animals than there had been at the start of World War I. Private plots accounted for at least one quarter of meat, dairy, and produce output.[citation needed] Living standards were low and consumer goods scarce. Moscow was also remarkably isolated and friendless on the international stage; Eastern Europe excluding Yugoslavia was held to the Soviet yoke by military occupation and soon after Stalin's death, protests and revolts would break out in some Eastern Bloc countries. China paid homage to the departed Soviet leader, but held a series of grudges that would soon boil over.[1][2] The United States had military bases and nuclear-equipped bomber aircraft surrounding the Soviet Union on three sides, and American aircraft regularly overflew Soviet territory on reconnaissance missions and to parachute agents in. Although the Soviet authorities shot down many of these aircraft and captured most of the agents dropped onto their soil, the psychological effect was immense.

American fears of Soviet military and especially nuclear capabilities were strong and heavily exaggerated; Moscow's only heavy bomber, the Tu-4, was a direct clone of the B-29 and had no way to get to the United States except on a one way suicide mission and the Soviet nuclear arsenal contained only a handful of weapons.

Policy Innovations by Beria

Domestic policy

As Deputy Premier of the Soviet Union, Lavrentiy Beria (notwithstanding his record as part of Stalin's terror state) initiated a period of relative liberalisation, including the release of some political prisoners. Almost as soon as Stalin was buried, Beria ordered Vyacheslav Molotov's wife freed from imprisonment and personally delivered her to the Soviet foreign minister.[citation needed] He also directed the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) to reexamine the Doctors' Plot and other "false" cases.[citation needed] Beria next proposed stripping the MVD of some of its economic assets and transferring control of them to other ministries, followed by the proposal to stop using forced labour on construction projects. He then announced that 1.1 million non-political prisoners were to be freed from captivity, that the Ministry of Justice should assume control of labour camps from the MVD, and that the Doctors' Plot was false. Finally, he ordered a halt to physical and psychological abuse of prisoners. Beria also declared a halt to forced Russification of the Soviet republics; Beria himself was a Georgian.

The leadership also began allowing some criticism of Stalin, saying that his one-man dictatorship went against the principles laid down by Vladimir Lenin. The war hysteria that characterized his last years was toned down, and government bureaucrats and factory managers were allowed to wear civilian clothing instead of military-style outfits. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were given serious prospects of national autonomy, possibly similarly to other Soviet satellite states in Europe.[3][4][5]

Foreign policy

Beria also turned his attention to foreign policy. A secret letter found among his papers after his death, suggested restoring relations with Titoist Yugoslavia.[citation needed] He also criticized Soviet handling of Eastern Europe and the numerous "mini-Stalins" such as Hungary's Mátyás Rákosi.[citation needed] East Germany particularly was in a tenuous situation in 1953 as the attempt by its leader Walter Ulbricht to impose all-out Stalinism had cause a mass exodus of people to the West. Beria suggested that East Germany should just be forgotten about entirely and there was "no purpose" for its existence. He revived the proposal Stalin had made to the Allies in 1946 for the creation of a united, neutral Germany.

Opposition to Beria

Beria displayed a considerable degree of contempt for the rest of the Politburo, letting it be known that they were "complicit" in Stalin's crimes.[citation needed] However, it was not deep-rooted ideological disagreements that turned them against Beria. Khrushchev in particular was appalled at the idea of abandoning East Germany and allowing the restoration of capitalism there, but that alone was not enough to plot Beria's downfall and he even supported the new, more enlightened policy towards non-Russian nationalities. The Politburo soon began stonewalling Beria's reforms and trying to prevent them from passing. One proposal, to reduce sentences handed down by the MVD to 10 years max, was later claimed by Khrushchev to be a ruse. "He wants to be able to sentence people to ten years in the camps, and then when they're freed, sentence them to another ten years. This is his way of grinding them down." Molotov was the strongest opponent of abandoning East Germany, and found in Khrushchev an unexpected ally.

By late June, it was decided that Beria could not simply be ignored or sidelined, he had to be taken out. They had him arrested on 26 June with the support of the armed forces.[6] At the end of the year, he was shot following a show trial where he was accused of spying for the West, committing sabotage, and plotting to restore capitalism. The secret police were disarmed and reorganized into the KGB, ensuring that they were completely under the control of the party and would never again be able to wage mass terror.

Collective leadership

For a time after Beria's deposition, Georgi Malenkov was generally considered the senior-most figure in the Politburo. Malenkov, an artistic-minded man who courted intellectuals and artists, had little use for bloodshed or state terror. He called for greater support of private agricultural plots and liberation of the arts from rigid socialist realism and he also criticized the pseudoscience of biologist Trofim Lysenko. In a November 1953 speech, Malenkov denounced corruption in various government agencies. He also reappraised Soviet views of the outside world and relations with the West, arguing that there were no disputes with the United States and her allies that could not be resolved peacefully, and that nuclear war with the West would simply bring about the destruction of all parties involved.

Within the same period, Nikita Khrushchev likewise emerged as a prominent figure in Soviet politics. Khrushchev proposed greater agricultural reforms, although he still refused to abandon the concept of collective farming and continued to support Lysenko's pseudoscience. In a 1955 speech, he argued that Soviet agriculture needed a shot in the arm and that it was silly to keep blaming low productivity and failed harvests on Tsar Nicholas II, dead for almost 40 years. He also began allowing ordinary people to stroll the grounds of the Kremlin, which had been closed off except to high ranking state officials for over 20 years.

The late Stalin's reputation meanwhile started diminishing. His 75th birthday in December 1954 had been marked by extensive eulogies and commemorations in the state media as was the second anniversary of his death in March 1955. However, his 76th birthday at the end of the year was hardly mentioned.

The new leadership declared a major amnesty for certain categories of convicts, announced price cuts, and relaxed the restrictions on private plots. De-Stalinisation would come to spell an end to the role of large-scale forced labour in the economy.

Conflict within the collective leadership

During the period of collective leadership, Khrushchev gradually rose to power while Malenkov's power waned. Malenkov was criticised for his economic reform proposals and desire to reduce the CPSU's direct involvement in the day-to-day running of the state. Molotov called his warning that nuclear war would end all of civilisation to be "nonsense" since according to Karl Marx, the collapse of capitalism was a historical inevitability. Khrushchev accused Malenkov of supporting Beria's plan to abandon East Germany, and of being a "capitulationist, social democrat, and a Menshevist".

Khrushchev was also headed for a showdown with Molotov, after having initially respected and left him alone in the immediate aftermath of Stalin's death. Molotov began criticizing some of Khrushchev's ideas and the latter accused him in turn of being an out-of-touch ideologue who never left his dacha or the Kremlin to visit farms or factories. Molotov attacked Khrushchev's suggestions for agricultural reform and also his plans to construct cheap, prefab apartments to alleviate Moscow's severe housing shortages. Khrushchev also endorsed restoring ties with Yugoslavia, the split with Belgrade having been heavily engineered by Molotov, who continued to denounce Tito as a fascist.[citation needed] A 1955 visit by Khrushchev to Yugoslavia patched up relations with that country, but Molotov refused to back down. The near-total isolation of the Soviet Union from the outside world was also blamed by Khrushchev on Molotov's handling of foreign policy and the former admitted in a speech to the Central Committee the obvious Soviet complicity in starting the Korean War.

20th Congress of the CPSU

At a closed session of the 20th Congress of the CPSU on 25 February 1956, Khrushchev shocked his listeners by denouncing Stalin's dictatorial rule and cult of personality in a speech entitled On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences. He also attacked the crimes committed by Stalin's closest associates. Furthermore, he stated that the orthodox view of war between the capitalist and communist worlds being inevitable was no longer true. He advocated competition with the West rather than outright hostility, stating that capitalism would decay from within and that world socialism would triumph peacefully. But, he added, if the capitalists did desire war, the Soviet Union would respond in kind.

De-Stalinisation

The impact of the 20th Congress on Soviet politics was immense. Khrushchev's speech stripped the legitimacy of his remaining Stalinist rivals, dramatically boosting his power domestically. Afterwards, Khrushchev eased restrictions and freed over a million prisoners from the Gulag, leaving an estimated 1.5 million prisoners living in a semi-reformed prison system (though a wave of counter-reform followed in the 1960s).[7][8] Communists around the world were shocked and confused by his condemnation of Stalin, and the speech "...caused a veritable revolution (the word is not too strong) in peoples attitudes throughout the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. It was the single factor in breaking down the mixture of fear, fanaticism, naivety and 'doublethink' with which everyone...had reacted to Communist rule".[9]

Among Soviet intellectuals

Many Soviet intellectuals groused that Khrushchev and the rest of the Central Committee had willingly aided and abetted Stalin's crimes and that the late tyrant could not possibly have done everything himself. Furthermore, they asked why it had taken three years to condemn him and noted that Khrushchev mostly criticised what had happened to fellow Party members while completely overlooking far greater atrocities such as the Holodomor and mass deportations from the Baltic States during and after World War II, none of which were allowed to be mentioned in the Soviet press until the end of the 1980s. During the Secret Speech, Khrushchev had tried in an awkward manner to explain why he and his colleagues had not raised their voices against Stalin by saying that they all feared their own destruction if they did not comply with his demands.

Pro-Stalin demonstrations

In Stalin's native Georgia, massive crowds of pro-Stalin demonstrators rioted in the streets of Tbilisi and even demanded that Georgia secede from the USSR. Army troops had to be called in to restore order, with 20 deaths, 60 injuries, and scores of arrests.

Response from Soviet youth

In April 1956, there were reports that Stalin busts and portraits around the country had been vandalized or pulled down and some student groups rioted and demanded that Stalin be posthumously expelled from the party and his body taken down from its spot next to Lenin. Party and student meetings called for proper rule of law in the country and even free elections. A 25 year old Mikhail Gorbachev, then a member of the Komsomol in Stavropol reported that reaction to the Secret Speech was explosive and there were strong reactions between people, particularly, young, educated people, who supported it and hated Stalin, others who denounced it and still held the late tyrant in awe, and others who thought it was irrelevant compared to grassroots issues such as food and housing availability. The Presidium responded by issuing a resolution condemning "anti-party" and "anti-Soviet" slanderers and the April 7 Pravda reprinted an editorial from China's People's Daily calling on party members to study Stalin's teachings and honour his memory. A Central Committee meeting on 30 June issued a resolution criticising Stalin merely for "serious errors" and "practicing a cult of personality" but holding the Soviet system itself blameless.

International reception

Some of the communist world, in particular China, North Korea, and Albania, stridently rejected de-Stalinisation. An editorial in the People's Daily argued that "Stalin made some mistakes, but on the whole he was a good, honest Marxist and his positives outweighed the negatives." Mao Zedong had many quarrels with Stalin, but thought that condemning him undermined the entire legitimacy of world socialism; "Stalin needed to be criticised, not killed" he said.[citation needed]

Rehabilitation during this period

By late 1955, thousands of political prisoners had been freed, but Soviet prisons and labour camps still held around 800,000 inmates and no attempt was made to investigate the Moscow Trials or rehabilitate their victims. Eventually several hundred thousand of Stalin's victims were rehabilitated, but the party officials purged in the Moscow Trials remained off the table. Khrushchev ordered an investigation into the trials of Mikhail Tukhachevsky and other army officers. The committee found that the charges leveled against them were baseless and their posthumous rehabilitation was announced in early 1957, but another investigation into the trials of Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, and Nikolai Bukharin declared that all three had engaged in "anti-Soviet activity" and would not be rehabilitated. After Khrushchev defeated the "anti-party group" in 1957, he promised to re-open the cases, but ultimately never did so, in part because of the embarrassing fact that he himself had celebrated the elimination of the Old Bolsheviks during the purges.

Changing toponymy

As part of de-Stalinisation, Khrushchev set about renaming the numerous towns, cities, factories, natural features, and kolkhozes around the country named in honor of Stalin and his aides, most notably Stalingrad, site of the great WWII battle, was renamed to Volgograd in 1961.

Khrushchev consolidates power

Defeat of the Anti-Party Group

In 1957, Khrushchev had defeated a concerted Stalinist attempt to recapture power, decisively defeating the so-called "Anti-Party Group"; this event illustrated the new nature of Soviet politics. The most decisive attack on the Stalinists was delivered by defense minister Georgy Zhukov, who and the implied threat to the plotters was clear; however, none of the "anti-party group" were killed or even arrested, and Khrushchev disposed of them quite cleverly: Georgy Malenkov was sent to manage a power station in Kazakhstan, and Vyacheslav Molotov, one of the most die-hard Stalinists, was made ambassador to Mongolia.

Eventually however, Molotov was reassigned to be the Soviet representative of the International Atomic Energy Commission in Vienna after the Kremlin decided to put some safe distance between him and China since Molotov was becoming increasingly cozy with the anti-Khrushchev Chinese Communist Party leadership. Molotov continued to attack Khrushchev every opportunity he got, and in 1960, on the occasion of Lenin's 90th birthday, wrote a piece describing his personal memories of the Soviet founding father and thus implying that he was closer to the Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. In 1961, just prior to the 22nd CPSU Congress, Molotov wrote a vociferous denunciation of Khrushchev's party platform and was rewarded for this action with expulsion from the party.

Khrushchev's attack on the "anti-party group" drew negative reactions from China; the People's Daily remarked "How can , one of the founding fathers of the CPSU, be a member of an anti-party group?"

Like Molotov, Foreign Minister Dmitri Shepilov also met the chopping block when he was sent to manage the Kirghizia Institute of Economics. Later, when he was appointed as a delegate to the Communist Party of Kirghizia conference, Khrushchev deputy Leonid Brezhnev intervened and ordered Shepilov dropped from the conference. He and his wife were evicted from their Moscow apartment and then reassigned to a smaller one that lay exposed to the fumes from a nearby food processing plant, and he was dropped from membership in the Soviet Academy of Sciences before being expelled from the party. Kliment Voroshilov held the ceremonial title of head of state despite his advancing age and declining health; he retired in 1960. Nikolai Bulganin ended up managing the Stavropol Economic Council. Also banished was Lazar Kaganovich, sent to manage a potash works in the Urals before being expelled from the party along with Molotov in 1962.

Despite his strong support for Khrushchev during the removal of Beria and the anti-party group, Zhukov was too popular and beloved of a figure for Khrushchev's comfort, so he was removed as well. In addition, while leading the attack against Molotov, Malenkov, and Kaganovich, he also insinuated that Khrushchev himself had been complicit in the 1930s purges, which in fact he had. While Zhukov was on a visit to Albania in October 1957, Khrushchev plotted his downfall. When Zhukov returned to Moscow, he was promptly accused of trying to remove the Soviet military from party control, creating a cult of personality around himself, and of plotting to seize power in a coup. Several Soviet generals went on to accuse Zhukov of "egomania", "shameless self-aggrandizement", and of tyrannical behaviour during WWII. Zhukov was expelled from his post as defense minister and forced into retirement from the military on the grounds of his "advanced age" (he was 62). Marshal Rodin Malinovsky took Zhukov's place as defense minister.

Election to Premiership

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_the_Soviet_Union_(1953–1964)Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk